The Development of Ru(II)-Based Photoactivated Chemotherapy Agents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

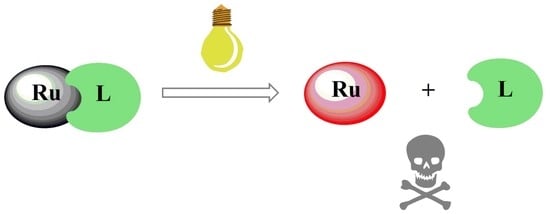

2. Ligand Photodissociation of Ru(II) Polypyridyl Complexes

2.1. Photodissociation of Monodentate Ligands

2.2. Photodissociation of Bidentate Ligands

3. Extending the Photoactivation Wavelength

4. Ru(II) PACT Agents with Multiple Functions

4.1. Ru(II) Complexes with Dual PACT and PDT Activity

4.2. The Combination of Ru(II)-Based PACT and Bioactive Ligands

4.3. Dual-Activatable Ru(II) PACT Agents

5. Ruthenium(II) Arene Complexes

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romero-Canelón, I.; Sadler, P.J. Next-generation metal anticancer complexes: Multitargeting via redox modulation. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12276–12291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjos, K.D.; Orvig, C. Metallodrugs in Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4540–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.; Kar, B.; Pete, S.; Paira, P. Ru(II), Ir(III), Re(I) and Rh(III) based complexes as next generation anticancer metallopharmaceuticals. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 11259–11290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.L.; He, H.Z.; Leung, K.H.; Chan, D.S.; Leung, C.H. Bioactive luminescent transition-metal complexes for biomedical applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7666–7682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohata, J.; Ball, Z.T. Rhodium at the chemistry-biology interface. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 14855–14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.L.; Wu, C.; Wu, K.J.; Leung, C.H. Iridium(III) Complexes Targeting Apoptotic Cell Death in Cancer Cells. Molecules 2019, 24, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omondi, R.O.; Ojwach, S.O.; Jaganyi, D. Review of comparative studies of cytotoxic activities of Pt(II), Pd(II), Ru(II)/(III) and Au(III) complexes, their kinetics of ligand substitution reactions and DNA/BSA interactions. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2020, 512, 119883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, B.; Vancamp, L.; Krigas, T. Inhibition of Cell Division in Escherichia coli by Electrolysis Products from a Platinum Electrode. Nature 1965, 205, 698–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, B.; VanCamp, L.; Trosko, J.E.; Mansour, V.H. Platinum Compounds: A new class of potent antitumor agents. Nature 1969, 222, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheate, N.J.; Walker, S.; Craig, G.E.; Oun, R. The status of platinum anticancer drugs in the clinic and in clinical trials. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 8113–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galanski, M.; Jakupec, M.A.; Keppler, B.K. Update of the Preclinical Situation of Anticancer Platinum Complexes: Novel Design Strategies and Innovative Analytical Approaches. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 2075–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.R.; Suntharalingam, K.; Johnstone, T.C.; Yoo, H.; Lin, W.; Brooks, J.G.; Lippard, S.J. Pt(IV) Prodrugs Designed to Bind Non-Covalently to Human Serum Albumin for Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8790–8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graf, N.; Bielenberg, D.R.; Kolishetti, N.; Muus, C.; Banyard, J.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Lippard, S.J. αVβ3 Integrin-Targeted PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles for Enhanced Anti-tumor Efficacy of a Pt(IV) Prodrug. ACS Nano. 2012, 6, 4530–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suntharalingam, K.; Song, Y.; Lippard, S.J. Conjugation of vitamin E analog α-TOS to Pt(IV) complexes for dual-targeting anticancer therapy. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 2465–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, T.C.; Suntharalingam, K.; Lippard, S.J. The Next Generation of Platinum Drugs: Targeted Pt(II) Agents, Nanoparticle Delivery, and Pt(IV) Prodrugs. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3436–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fanelli, M.; Formica, M.; Fusi, V.; Giorgi, L.; Micheloni, M.; Paoli, P. New trends in platinum and palladium complexes as antineoplastic agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 310, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, N.J.; Woods, J.A.; Salassa, L.; Zhao, Y.; Robinson, K.S.; Clarkson, G.; Mackay, F.S.; Sadler, P.J. A Potent Trans-Diimine Platinum Anticancer Complex Photoactivated by Visible Light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 8905–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasparkova, J.; Kostrhunova, H.; Novakova, O.; Křikavová, R.; Va nčo, J.; Trávníčk, Z.; Brabec, V. A Photoactivatable Platinum(IV) Complex Targeting Genomic DNA and Histone Deacetylases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14478–14482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, N.J.; Salassa, L.; Sadler, P.J. Photoactivated chemotherapy (PACT): The potential of excited-state d-block metals in medicine. Dalton Trans. 2009, 10690–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imberti, C.; Zhang, P.; Huang, H.; Sadler, P.J. New Designs for Phototherapeutic Transition Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, S. Why develop photoactivated chemotherapy? Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 10330–10343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detty, M.R.; Gibson, S.L.; Wagner, S.J. Current Clinical and Preclinical Photosensitizers for Use in Photodynamic Therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 3897–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Huang, P.; Chen, X. Overcoming the Achilles’ heel of photodynamic therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 6488–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eales, K.L.; Hollinshead, K.E.R.; Tennant, D.A. Hypoxia and metabolic adaptation of cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cosse, J.P.; Michiels, C. Tumour hypoxia affects the responsiveness of cancer cells to chemotherapy and promotes cancer progression. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagesan, M.; Sathyadevi, P.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Bhuvanesh, N.S.; Dharmaraj, N. DMSO containing ruthenium(II) hydrazone complexes: In vitro evaluation of biomolecular interaction and anticancer activity. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 15829–15840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thota, S.; Rodrigues, D.A.; Crans, D.C.; Barreiro, E.J. Ru(II) Compounds: Next-Generation Anticancer Metallotherapeutics? J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5805–5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, A.; Gasser, G. Monomeric and dimeric coordinatively saturated and substitutionally inert Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes as anticancer drug candidates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 7317–7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Li, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q. Ruthenium Complexes as Promising Candidates against Lung Cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynton, F.E.; Bright, S.A.; Blasco, S.; Williams, D.C.; Kelly, J.M.; Gunnlaugsson, T. The development of ruthenium(II) polypyridylcomplexes and conjugates for in vitro cellular and in vivo applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 7706–7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, A.; Zorzet, S.; Gava, B.; Sorc, A.; Alessio, E.; Iengo, E.; Sava, G. Effects of NAMI-A and some related ruthenium complexes on cell viability after short exposure of tumor cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2000, 11, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratsos, I.; Jedner, S.; Gianferrara, T.; Alessio, E. Ruthenium Anticancer Compounds: Challenges and Expectations. CHIMIA 2007, 61, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker-Lakhai, J.M.; van den Bongard, D.; Pluim, D.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H. A Phase I and Pharmacological Study with Imidazolium-trans-DMSO-imidazole-tetrachlororuthenate, a Novel Ruthenium Anticancer Agent. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 3717–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartinger, C.G.; Zorbas-Seifried, S.; Jakupec, M.A.; Kynast, B.; Zorbas, H.; Keppler, B.K. From bench to bedside—preclinical and early clinical development of the anticancer agent indazolium trans-[tetrachlorobis(1H-indazole)ruthenate(III)] (KP1019 or FFC14A). J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006, 100, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bytzek, A.K.; Koellensperger, G.; Keppler, B.K.; Hartinger, C.G. Biodistribution of the novel anticancer drug sodium trans-[tetrachloridobis(1H-indazole)ruthenate(III)] KP-1339/IT139 in nude BALB/c mice and implications on its mode of action. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 160, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijen, S.; Burgers, S.A.; Baas, P.; Pluim, D.; Tibben, M.; Werkhoven, E.; Alessio, E.; Sava, G.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H.M. Phase I/II study with ruthenium compound NAMI-A and gemcitabine in patients with non-small cell lung cancer after first line therapy. Investig. New Drugs. 2015, 33, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Monro, S.; Colón, K.L.; Yin, H.; Roque, J.; Konda, P.; Gujar, S.; Thummel, R.P.; Lilge, L.; Gameron, C.G.; McFarland, S.A. Transition Metal Complexes and Photodynamic Therapy from a Tumor-Centered Approach: Challenges, Opportunities, and Highlights from the Development of TLD1433. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 797–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, C.; Pierroz, V.; Ferrari, S.; Gasser, G. Combination of Ru(II) complexes and light: New frontiers in cancer therapy. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2660–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knoll, J.D.; Turro, C. Control and utilization of ruthenium and rhodium metal complex excited states for photoactivated cancer therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 282, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, L.; Gupta, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, E.; Ji, L.; Chao, H.; Chen, Z.S. The development of anticancer ruthenium(II) complexes: From single molecule compounds to nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5771–5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Turro, C.; Kodanko, J.J. Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes as photocages for bioactive compounds containing nitriles and aromatic heterocycles. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.X.; Lippard, S.J. New metal complexes as potential therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003, 7, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, N.; Welch, T.W.; Fairley, T.A.; Cory, M.; Thorp, H.H. Covalent Binding of Aquaruthenium complexes to DNA. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 3544–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M.R.; Thomas, J.A. Ruthenium (II) polypyridyl complexes and DNA-from structural probes to cellular imaging and therapeutics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3179–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albani, B.A.; Peña, B.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. New cyclometallated Ru(II) complex for potential application in photochemotherapy. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 13, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durham, B.; Walsh, J.L.; Carter, C.L.; Meyer, T.J. Synthetic applications of photosubstitution reactions of poly(pyridyl) complexes of ruthenium(II). Inorg. Chem. 1980, 19, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, N.Y.; Deng, Y.Q.; Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.W. Photoinduced DNA Cleavage and Photocytotoxic of Phenanthroline-Based Ligand Ruthenium Compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.X.; Lei, W.H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.R.; Li, C.; Hou, Y.J.; Wang, X.S.; Zhang, B.W. [Ru(bpy)3-n(dpb)n]2+: Unusual Photophysical Property and Efficient DNA Photocleavage Activity. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 4729–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubaszek, M.; Goud, B.; Ferrari, S.; Gasser, G. Mechanisms of action of Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes in living cells upon light irradiation. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 13040–13059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, T.N.; Turro, C. Photoinitiated DNA Binding by cis-[Ru(bpy)2(NH3)2]2+. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 7260–7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillema, D.P.; Blanton, C.B.; Shaver, R.J.; Jackman, D.C.; Bolda-ji, M.; Bundy, S.; Worl, L.A.; Meyer, T.J. MLCT-dd Energy Gap in Pyridyl-Pyrimidine and Bis( pyridine) Complexes of Ruthenium(II). Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 1600–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Turner, D.B.; Singh, T.N.; Angeles-Boza, A.M.; Chouai, A.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. Ultrafast ligand exchange: Detection of a pentacoordinate Ru(II) intermediate and product formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayanuma, M.; Shoji, M.; Shigeta, Y. Photosubstitution Reaction of cis-[Ru(bpy)2(CH3CN)2]2+ and cis-[Ru(bpy)2(NH3)2]2+ in Aqueous Solution via Monoaqua Intermediate. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 2497–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrylyuk, D.; Deshpande, M.; Parkin, S.; Glazer, E.C. Ru(II) complexes with diazine ligands: Electronic modulation of the coordinating group is key to the design of “dual action” photoactivated agents. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 12487–12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; White, J.K.; Sharma, R.; Mazumder, S.; Martin, P.D.; Schlegel, H.B.; Turro, C.; Kodanko, J.K. Effects of Methyl Substitution in Ruthenium Tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine Photocaging Groups for Nitriles. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 6968–6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, A.; Turro, C.; Kodanko, J.J. Ru(II) Polypyridyl Complexes Derived from Tetradentate Ancillary Ligands for Effective Photocaging. Acc. Chem Res. 2018, 51, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, J.D.; Albani, B.A.; Durr, C.B.; Turro, C. Unusually Efficient Pyridine Photodissociation from Ru(II) Complexes with Sterically Bulky Bidentate Ancillary Ligands. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 10603–10610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albani, B.A.; Durr, C.B.; Turro, C. Selective photoinduced ligand exchange in a new tris-heteroleptic Ru(II) complex. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 13885–13892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrylyuk, D.; Stevens, K.; Parkin, S.; Glazer, E.C. Toward Optimal Ru(II) Photocages: Balancing Photochemistry, Stability, and Biocompatibility Through Fine Tuning of Steric, Electronic, and Physiochemical Features. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerhan, R.; Sun, W.; Tian, N.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, C.; Cheng, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. Fluorination on non-photolabile dppz ligands for improving Ru(II) complex-based photoactivated chemotherapy. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 12177–12185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Jin, Z.; Jian, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. Photo-induced mitochondrial DNA damage and NADH depletion by -NO2 modified Ru(II) complexes. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 4162–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, R.N.; Joyce, L.E.; Turro, C. Effect of electronic structure on the photoinduced ligand exchange of Ru(II) polypyridine complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 4384–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howerton, B.S.; Heidary, D.K.; Glazer, E.C. Strained ruthenium complexes are potent light-activated anticancer agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8324–8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayatullah, A.N.; Wachter, E.; Heidary, D.K.; Parkin, S.; Glazer, E.C. Photoactive Ru(II) complexes with dioxinophenanthroline ligands are potent cytotoxic agents. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 10030–10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, D.F.; Audi, H.; Farhat, S.; El-Sibai, M.; Abi-Habib, R.J.; Khnayzer, R.S. Phototoxicity of strained Ru(II) complexes: Is it the metal complex or the dissociating ligand? Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 11529–11532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wachter, E.; Heidary, D.K.; Howerton, B.S.; Parkin, S.; Glazer, E.C. Light-activated ruthenium complexes photobind DNA and are cytotoxic in the photodynamic therapy window. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9649–9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, M.; Howerton, B.; Baeb, Y.; Glazer, E.C. Light-sensitive ruthenium complex-loaded cross-linked polymeric nanoassemblies for the treatment of cancer. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2016, 4, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bataglioli, J.C.; Gomes, L.M.F.; Maunoir, C.; Smith, J.R.; Cole, H.D.; McCain, J.; Sainuddin, T.; Cameron, C.G.; McFarland, S.A.; Storr, T. Modification of amyloid-beta peptide aggregation via photoactivation of strained Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 7510–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuello-Garibo, J.; Meijer, M.S.; Bonnet, S. To cage or to be caged? The cytotoxic species in ruthenium-based photoactivated chemotherapy is not always the metal. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 6768–6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuello-Garibo, J.A.; James, C.C.; Siegler, M.A.; Bonnet, S. Ruthenium-based PACT compounds based on an N,S non-toxic ligand: A delicate balance between photoactivation and thermal stability. Chem. Sq. 2017, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, A.E.; Chambron, J.C.; Sauvage, J.P.; Turro, N.J.; Bar-ton, J.K. A molecular light switch for DNA: Ru(bpy)2(dppz)2+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4960–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, E.; Howerton, B.S.; Hall, E.C.; Parkin, S.; Glazer, E.C. A new type of DNA “light-switch”: A dual photochemical sensor and metalating agent for duplex and G-quadruplex DNA. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, E.; Glazer, E.C. Mechanistic study on the photochemical “light switch” behavior of [Ru(bpy)2dmdppz]2+. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 10474–10486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrylyuk, D.; Heidary, D.K.; Sun, Y.; Parkin, S.; Glazer, E.C. Photochemical and Photobiological Properties of Pyridyl-pyrazol(in)e-Based Ruthenium(II) Complexes with Sub-micromolar Cytotoxicity for Phototherapy. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 18894–18906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, J.M.; Arnaut, L.G. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) of cancer: From local to systemic treatment. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 1765–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, S.L.; Siewert, B.; Askes, S.H.C.; Veldhuizen, P.; Zwier, R.; Heger, M.; Bonnet, S. An In Vitro Cell Irradiation Protocol for Testing Photopharmaceuticals and the Effect of Blue, Green, and Red Light on Human Cancer Cell Lines. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2016, 15, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vogel, A.; Venugopalan, V. Mechanisms of Pulsed Laser Ablation of Biological Tissues. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 577–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, X.; Da, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. A Ru-anthraquinone dyad with triple functions of PACT, photoredox catalysis and PDT upon red light Irradiation. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 10845–10852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, R.B.; Joyce, L.E.; Ojaimi, M.; Gallucci, J.C.; Thummel, R.P.; Turro, C. Photoinduced ligand exchange and DNA binding of cis-[Ru(phpy)(phen)(CH3CN)2]+ with long wavelength visible light. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 121, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuello-Garibo, J.A.; James, C.C.; Siegler, M.A.; Hopkins, S.L.; Bonnet, S. Selective Preparation of a Heteroleptic Cyclometallated Ruthenium Complex Capable of Undergoing Photosubstitution of a Bidentate Ligand. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Afyouni, M.H.; Rohrabaugh, T.N.; Al-Afyouni, K.F.; Turro, C. New Ru(ii) photocages operative with near-IR light: New platform for drug delivery in the PDT window. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 6711–6720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; McCarthy, W.; Conway-Kenny, R.; Twamley, B.; Zhao, J.Z.; Drapera, S.M. Novel ruthenium and iridium complexes of N-substituted carbazole as triplet photosensitisers. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadman, S.H.; Havenith, R.W.A.; Hartl, F.; Lutz, M.; Spek, A.L.; van Klink, G.P.M.; van Koten, G. Redox Chemistry and Electronic Properties of 2,3,5,6-Tetrakis(2-pyridyl)pyrazine-Bridged Diruthenium Complexes Controlled by N,C,N′-BisCyclometalated Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 5685–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ruminski, R.R.; Degroff, C.; Smith, S.J. Synthesis and characterization of tetracarbonylmolybdenum(0) complexes bound to the novel bridging ligand dipyrido[2,3-a:2′,3′-h]phenazine (DPOP). Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 3325–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albani, B.A.; Peña, B.; Saha, S.; White, J.K.; Schaeffer, A.M.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. A dinuclear Ru(II) complex capable of photoinduced ligand exchange at both metal centers. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 16522–16525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Peña, B.; Dunbar, K.R. Partially Solvated Dinuclear Ruthenium Compounds Bridged by Quinoxaline-Functionalized Ligands as Ru(II) Photocage Architectures for Low-Energy Light Absorption. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 14568–14576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Thiramanas, R.; Schwendy, M.; Xie, C.; Parekh, S.H.; Mailänder, V.; Wu, S. Upconversion Nanocarriers Encapsulated with Photoactivatable Ru Complexes for Near-Infrared Light-Regulated Enzyme Activity. Small 2017, 13, 1700997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, E.; Habtemariam, A.; Yate, L.; Mareque-Rivas, J.C.; Salassa, L. Near Infrared Photolysis of a Ru Polypyridyl Complex by Upconverting Nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Fang, T.; Tian, Y.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y. A Dual-Fluorescent Nano-Carrier for Delivering Photoactive Ruthenium Polypyridyl Complexes. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 4746–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, G.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X. An upconversion nanoparticle/Ru(II) polypyridyl complex assembly for NIR-activated release of a DNA covalent-binding agent. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 23804–23808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, X.; Da, X.; Yao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. UCNP@BSA@Ru nanoparticles with tumor-specific and NIR-triggered efficient PACT activity in vivo. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 7715–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, M.S.; Natile, M.M.; Bonnet, S. 796 nm Activation of a Photocleavable Ruthenium(II) Complex Conjugated to an Upconverting Nanoparticle through Two Phosphonate Groups. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 14807–14818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenough, S.E.; Horbury, M.D.; Smith, N.A.; Sadler, P.J.; Pater-son, M.J.; Stavros, V.G. Excited-State Dynamics of a Two-Photon-Activatable Ruthenium Prodrug. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ávila, M.R.; León-Rojas, A.F.; Lacroix, P.G.; Malfant, I.; Farfán, N.; Mhanna, R.; Santillan, R.; Ramos-Ortiz, G.; Malval, J.P. Two-Photon-Triggered NO Release via a Ruthenium–Nitrosyl Complex with a Star-Shaped Architecture. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 6487–6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xie, C.; Lan, R.; Zha, S.; Chan, C.; Wong, W.; Ho, K.; Chan, B.D.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. A Smart Europium−Ruthenium Complex as Anticancer Prodrug: Controllable Drug Release and Real-Time Monitoring under Different Light Excitations. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 8923–8932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, N.; Sun, W.; Rena, B.; Guo, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. A Ru(II)-Based Nanoassembly Exhibiting Theranostic PACT Activity in NIR Region. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2020, 37, 2000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Qi, S.; Guo, X.; Jian, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. The modification of a pyrene group makes a Ru(II) complex versatile. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 3259–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albani, B.A.; Peña, B.; Leed, N.A.; de Paula, N.A.B.G.; Pavani, C.; Baptista, M.S.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. Marked improvement in photoinduced cell death by a new tris-heteroleptic complex with dual action: Singlet oxygen sensitization and ligand dissociation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17095–17101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, J.D.; Albani, B.A.; Turro, C. Excited state investigation of a new Ru(II) complex for dual reactivity with low energy light. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 8777–8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knoll, J.D.; Albani, B.A.; Turro, C. New Ru(II) Complexes for Dual Photoreactivity: Ligand Exchange and 1O2 Generation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2280–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loftus, L.M.; White, J.K.; Albani, B.A.; Kohler, L.; Kodanko, J.K.; Thummel, R.P.; Dunba, K.R.; Turro, C. New RuII Complex for Dual Activity: Photoinduced Ligand Release and 1O2 Production. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 3704–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arora, K.; Herroon, M.; Al-Afyouni, M.H.; Toupin, N.P.; Rohrabaugh, T.N.; Loftus, L.M.; Podgorski, I.; Turro, C.; Kodanko, J.J. Catch and Release Photosensitizers: Combining Dual-Action Ruthenium Complexes with Protease Inactivation for Targeting Invasive Cancers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14367–14380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toupin, N.P.; Nadella, S.; Steinke, S.J.; Turro, C.; Kodanko, J.J. Dual-Action Ru(II) Complexes with Bulky π-Expansive Ligands: Phototoxicity without DNA Intercalation. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 3919–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Q.X.; Lei, W.H.; Hou, Y.J.; Li, K.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhang, B.W.; Wang, X.S. DNA photocleavage in anaerobic conditions by a Ru(II) complex: A new mechanism. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Q.X.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, C.; Hou, Y.J.; Wang, X.S. Substituent effect and wavelength dependence of the photoinduced Ru-O homolysis in the [Ru(bpy)2(py-SO3)]+-type complexes. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 2897–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tian, N.; Feng, Y.; Sun, W.; Lu, J.; Lu, S.; Yao, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. A nuclear permeable Ru(II)-based photoactivated chemotherapeutic agent towards a series of cancer cells: In vitro and in vivo studies. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 6492–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Dasari, S.; Patra, A.K. Ruthenium(II) complexes of saccharin with dipyridoquinoxaline and dipyridophenazine: Structures, biological interactions and photoinduced DNA damage activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 136, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamer, B.N.; Gallucci, J.C.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. [Ru(bpy)2(5-cyanouracil)2]2+ as a Potential Light-Activated Dual-Action Therapeutic Agent. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 9213–9215. [Google Scholar]

- Sgambellone, M.A.; David, A.; Garner, R.N.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. Cellular Toxicity Induced by the Photorelease of a Caged Bioactive Molecule: Design of a Potential Dual-Action Ru(II) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11274–11282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameijer, L.N.; Ernst, D.; Hopkins, S.L.; Meijer, M.S.; Askes, S.H.C.; Le Devedec, S.E.; Bonnet, S. A Red-Light-Activated Ruthenium-Caged NAMPT Inhibitor Remains Phototoxic in HypoxicCancer Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11549–11553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.H.; Renfrew, A.K. Photolabile Ruthenium Complexes to Cage and Release a Highly Cytotoxic Anticancer Agent. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 179, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoun, N.; Renfrew, A.K. A Luminescent Ruthenium(II) Complex for Light-Triggered Drug Release and Live Cell Imaging. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 14038–14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.A.; Zhang, P.Y.; Greenough, S.E.; Horbury, M.D.; Clarkson, G.J.; McFeely, D.; Habtemariam, A.; Salassa, L.; Stavros, V.G.; Dowson, C.G.; et al. Combatting AMR: Photoactivatable Ruthenium(II)-Isoniazid Complex Exhibits Rapid Selective Antimycobacterial Activity. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herroon, M.K.; Sharma, R.; Rajagurubandara, E.; Turro, C.; Kodanko, J.J.; Podgorski, I. Photoactivated Inhibition of Cathepsin K in a 3D Tumor Model. Biol. Chem. 2016, 397, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zamora, A.; Denning, C.A.; Heidary, D.K.; Wachter, E.; Nease, L.A.; Ruiz, J.; Glazer, E.C. Ruthenium-Containing p450 Inhibitors for Dual Enzyme Inhibition and DNA Damage. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 2165–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Yadav, R.; White, J.K.; Herroon, M.K.; Callahan, B.P.; Podgorski, I.; Turro, C.; Scott, E.E.; Kodanko, J.J. Illuminating Cytochrome P450 Binding: Ru(II)-Caged Inhibitors of CYP17A1. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 3673–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.X.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.J.; Chen, Y.J.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, C.; Hou, Y.J.; Wang, X.-S. A novel azopyridine-based Ru(ii) complex with GSH-responsive DNA photobinding ability. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 10684–10686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Park, S.; Martinez, K.; Gray, J.L.; Thowfeik, F.S.; Lundeen, J.A.; Kuhn, A.E.; Charboneau, D.J.; Gerlach, D.L.; Lockart, M.M.; et al. Ruthenium Complexes are pH-Activated Metallo Prodrugs (pHAMPs) with Light-Triggered Selective Toxicity Toward Cancer Cells. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 7519–7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.; Martinez, K.; Arcidiacono, A.M.; Park, S.; Zeller, M.; Schmehl, R.H.; Paul, J.J.; Kim, Y.; Papish, E.T. Sterically demanding methoxy and methyl groups in ruthenium complexes lead to enhanced quantum yields for blue light triggered photodissociation. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 15685–15693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.; Lamb, R.W.; Cameron, C.G.; Park, S.; Oladipupo, O.; Gray, J.L.; Xu, Y.; Cole, H.D.; Bonizzoni, M.; Kim, Y.; et al. Singlet Oxygen Formation vs. Photodissociation for Light Responsive Protic Ruthenium Anticancer Compounds: The Oxygenated Substituent Determines Which Pathway Dominates. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Feng, Q.; Duan, X.; Wang, S.; Tang, Y. CO/light dual-activatable Ru(II)-conjugated oligomer agent for lysosome-targeted multimodal cancer therapeutics. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 11515–11524, Advance Article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suss-Fink, G. Arene ruthenium complexes as anticancer agents. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 1673–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, C.Y.; Nam, T.G. Ruthenium Complexes as Anticancer Agents: A Brief History and Perspectives. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2020, 14, 5375–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magennis, S.W.; Habtemariam, A.; Novakova, O.; Henry, J.B.; Meier, S.; Parsons, S.; Oswald, L.D.H.; Brabec, V.; Sadler, P.J. Dual Triggering of DNA Binding and Fluorescence via Photoactivation of a Dinuclear Ruthenium(II) Arene Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 5059–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betanzos-Lara, S.; Salassa, L.; Habtemariam, A.; Sadler, P.J. Photocontrolled nucleobase binding to an organometallic RuII arene complex. Chem. Commun. 2009, 43, 6622–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betanzos-Lara, S.; Salassa, L.; Habtemariam, A.; Novakova, O.; Pizarro, A.M.; Clarkson, G.J.; Liskova, B.; Brabec, V.; Sadler, P.J. Photoactivatable Organometallic Pyridyl Ruthenium(II) Arene Complexes. Organometallics 2012, 31, 3466–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán, F.; López-Senín, P.; Salassa, L.; Betanzos-Lara, S.; Habtemariam, A.; Moreno, V.; Sadler, P.J.; Marchán, V. Photocontrolled DNA Binding of a Receptor-Targeted OrganometallicRuthenium(II) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14098–14108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Q.X.; Lei, W.H.; Hou, Y.J.; Chen, Y.J.; Li, C.; Zhang, B.W.; Wang, X.S. BODIPY-modified Ru(II) arene complex—a new ligand dissociation mechanism and a novel strategy to red shift the photoactivation wavelength of anticancer Metallodrugs. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 2786–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Zhou, Q.X.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, W.B.; Hou, Y.J.; Jiang, G.Y.; Cheng, X.X.; Wang, X.S. A ferrocenyl pyridine-based Ru(ii) arene complex capable of generating ·OH and 1O2 along with photoinduced ligand dissociation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 45652–45659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Lei, W.H.; Jiang, G.Y.; Hou, Y.J.; Li, C.; Zhang, B.W.; Zhou, Q.X.; Wang, X.S. Fusion of photodynamic therapy and photoactivated chemotherapy: A novel Ru(II) arene complex with dual activities of photobinding and photocleavage toward DNA. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 15375–15384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Lei, W.H.; Hou, Y.J.; Li, C.; Jiang, G.Y.; Zhang, B.W.; Zhou, Q.X.; Wang, X.S. Fine control on the photochemical and photobiological properties of Ru(II) arene complexes. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 7347–7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lari, M.; Martínez-Alonso, M.; Busto, N.; Manzano, B.R.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Acuna, M.I.; Domínguez, F.; Albasanz, J.L.; Leal, J.M.; Espino, G.; et al. Strong Influence of Ancillary Ligands Containing Benzothiazole or Benzimidazole Rings on Cytotoxicity and Photoactivation of Ru(II) Arene Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 14322–14336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Bai, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q. The Development of Ru(II)-Based Photoactivated Chemotherapy Agents. Molecules 2021, 26, 5679. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules26185679

Chen Y, Bai L, Zhang P, Zhao H, Zhou Q. The Development of Ru(II)-Based Photoactivated Chemotherapy Agents. Molecules. 2021; 26(18):5679. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules26185679

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yongjie, Lijuan Bai, Pu Zhang, Hua Zhao, and Qianxiong Zhou. 2021. "The Development of Ru(II)-Based Photoactivated Chemotherapy Agents" Molecules 26, no. 18: 5679. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/molecules26185679