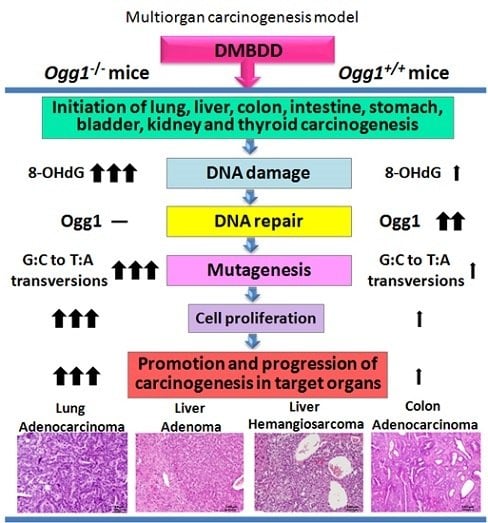

Enhanced Susceptibility of Ogg1 Mutant Mice to Multiorgan Carcinogenesis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. General Observations

2.2. Survival Curves

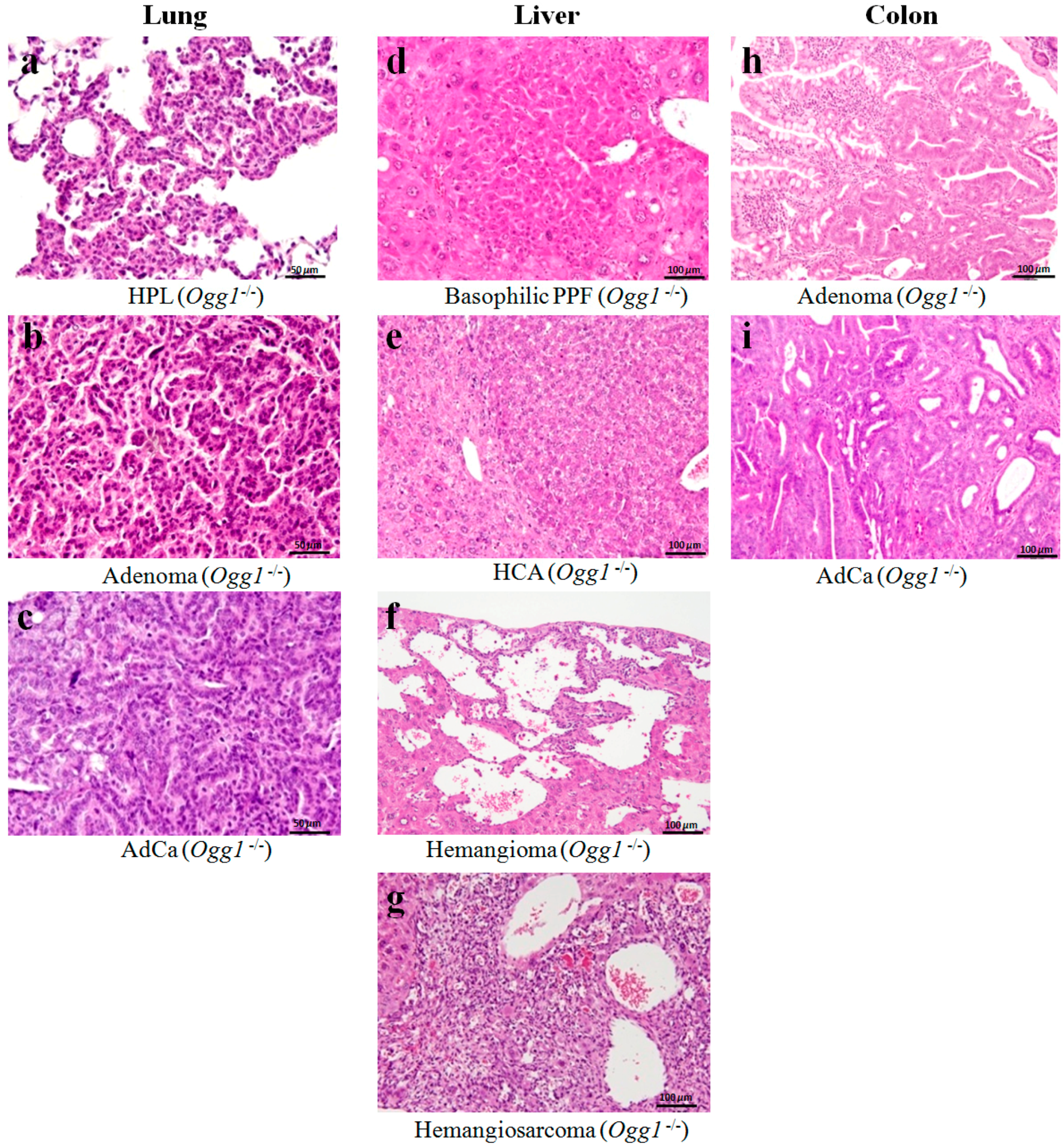

2.3. Results of Histopathological Examination

2.4. Blood Biochemistry

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Animals

4.3. Experimental Design

4.4. Blood Biochemical Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anisimov, V.N.; Alimova, I.N. The use of mutagenic and transgenic mice for the study of aging mechanisms and age pathology. Adv. Gerontol. 2001, 7, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kasai, H. Analysis of a form of oxidative DNA damage, 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, as a marker of cellular oxidative stress during carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 1997, 387, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakae, D.; Kobayashi, Y.; Akai, H.; Andoh, N.; Satoh, H.; Ohashi, K.; Tsutsumi, M.; Konishi, Y. Involvement of 8-hydroxyguanine formation in the initiation of rat liver carcinogenesis by low dose levels of N-nitrosodiethylamine. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klungland, A.; Rosewell, I.; Hollenbach, S.; Larsen, E.; Daly, G.; Epe, B.; Seeberg, E.; Lindahl, T.; Barnes, D.E. Accumulation of premutagenic DNA lesions in mice defective in removal of oxidative base damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13300–13305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakumi, K.; Tominaga, Y.; Furuichi, M.; Xu, P.; Tsuzuki, T.; Sekiguchi, M.; Nakabeppu, Y. Ogg1 knockout-associated lung tumorigenesis and its suppression by Mth1 gene disruption. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Slupska, M.M.; Baikalov, C.; Luther, W.M.; Chiang, J.H.; Wei, Y.F.; Miller, J.H. Cloning and sequencing a human homolog (hMYH) of the Escherichia coli mutY gene whose function is required for the repair of oxidative DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 1996, 178, 3885–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburatani, H.; Hippo, Y.; Ishida, T.; Takashima, R.; Matsuba, C.; Kodama, T.; Takao, M.; Yasui, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Asano, M. Cloning and characterization of mammalian 8-hydroxyguanine-specific DNA glycosylase/apurinic, apyrimidinic lyase, a functional mutM homologue. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 2151–2156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arai, T.; Kelly, V.P.; Minowa, O.; Noda, T.; Nishimura, S. High accumulation of oxidative DNA damage, 8-hydroxyguanine, in Mmh/Ogg1 deficient mice by chronic oxidative stress. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 2005–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radicella, J.P.; Dherin, C.; Desmaze, C.; Fox, M.S.; Boiteux, S. Cloning and characterization of hOGG1, a human homolog of the OGG1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 8010–8015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenquist, T.A.; Zharkov, D.O.; Grollman, A.P. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 7429–7434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, M.L.; Tchou, J.; Grollman, A.P.; Miller, J.H. A repair system for 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydrodeoxyguanine. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 10964–10968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, M.L.; Cruz, C.; Grollman, A.P.; Miller, J.H. Evidence that MutY and MutM combine to prevent mutations by an oxidatively damaged form of guanine in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 7022–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minowa, O.; Arai, T.; Hirano, M.; Monden, Y.; Nakai, S.; Fukuda, M.; Itoh, M.; Takano, H.; Hippou, Y.; Aburatani, H.; et al. Mmh/Ogg1 gene inactivation results in accumulation of 8-hydroxyguanine in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 4156–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, A.; Wanibuchi, H.; Morimura, K.; Wei, M.; Nakae, D.; Arai, T.; Minowa, O.; Noda, T.; Nishimura, S.; Fukushima, S. Carcinogenicity of dimethylarsinic acid in Ogg1-deficient mice. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakehashi, A.; Ishii, N.; Okuno, T.; Fujioka, M.; Gi, M.; Fukushima, S.; Wanibuchi, H. Progression of hepatic adenoma to carcinoma in Ogg1 mutant mice induced by phenobarbital. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, T.; Kelly, V.P.; Komoro, K.; Minowa, O.; Noda, T.; Nishimura, S. Cell proliferation in liver of Mmh/Ogg1-deficient mice enhances mutation frequency because of the presence of 8-hydroxyguanine in DNA. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 4287–4292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Yang, H.; Cunanan, C.; Okamoto, K.; Shibata, D.; Pan, J.; Barnes, D.E.; Lindahl, T.; McIlhatton, M.; Fishel, R.; Miller, J.H. Deficiencies in mouse Myh and Ogg1 result in tumor predisposition and G to T mutations in codon 12 of the K-ras oncogene in lung tumors. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 3096–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Hasegawa, R.; Masui, T.; Mizoguchi, M.; Fukushima, S.; Ito, N. Establishment of multiorgan carcinogenesis bioassay using rats treated with a combination of five carcinogens. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 1992, 5, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Hasegawa, R.; Imaida, K.; Hirose, M.; Shirai, T. Medium-term liver and multi-organ carcinogenesis bioassays for carcinogens and chemopreventive agents. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 1996, 48, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaida, K.; Tamano, S.; Hagiwara, A.; Fukushima, S.; Shirai, T.; Ito, N. Application of rat medium-term bioassays for detecting carcino-genic and modifying potentials of endocrine active substances. Pure Appl. Chem. 2003, 75, 2491–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, S.; Morimura, K.; Wanibuchi, H.; Kinoshita, A.; Salim, E.I. Current and emerging challenges in toxicopathology: Carcinogenic threshold of phenobarbital and proof of arsenic carcinogenicity using rat medium-term bioassays for carcinogens. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 207, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, S.; Hagiwara, A.; Hirose, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Tiwawech, D.; Ito, N. Modifying effects of various chemicals on preneoplastic and neoplastic lesion development in a wide-spectrum organ carcinogenesis model using F344 rats. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1991, 82, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, R.; Furukawa, F.; Toyoda, K.; Takahashi, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Hirose, M.; Ito, N. Inhibitory effects of antioxidants on N-bis(2-hydroxypropyl)nitrosamine-induced lung carcinogenesis in rats. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1990, 81, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, N.; Hirose, M.; Fukushima, S.; Tsuda, H.; Shirai, T.; Tatematsu, M. Studies on antioxidants: Their carcinogenic and modifying effects on chemical carcinogenesis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1986, 24, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, T.; Masuda, A.; Imaida, K.; Ogiso, T.; Ito, N. Effects of phenobarbital and carbazole on carcinogenesis of the lung, thyroid, kidney, and bladder of rats pretreated with N-bis(2-hydroxypropyl)nitrosamine. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1988, 79, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, N.; Wei, M.; Kakehashi, A.; Doi, K.; Yamano, S.; Inaba, M.; Wanibuchi, H. Enhanced Urinary Bladder, Liver and Colon Carcinogenesis in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats in a Multiorgan Carcinogenesis Bioassay: Evidence for Mechanisms Involving Activation of PI3K Signaling and Impairment of p53 on Urinary Bladder Carcinogenesis. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 2011, 24, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuzuki, T.; Egashira, A.; Igarashi, H.; Iwakuma, T.; Nakatsuru, Y.; Tominaga, Y.; Kawate, H.; Nakao, K.; Nakamura, K.; Ide, F.; et al. Spontaneous tumorigenesis in mice defective in the MTH1 gene encoding 8-oxo-dGTPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 11456–11461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, A.; Tsukamoto, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Sakai, H.; Yanai, T.; Masegi, T.; Donehower, L.A.; Tatematsu, M. Organ-specific susceptibility of p53 knockout mice to N-bis(2-hydroxypropyl)nitrosamine carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2006, 238, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi, M.; Masutani, M.; Nozaki, T.; Kusuoka, O.; Tsujiuchi, T.; Nakagama, H.; Suzuki, H.; Konishi, Y.; Sugimura, T. Increased susceptibility of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 knockout mice to nitrosamine carcinogenicity. Carcinogenesis 2001, 22, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Miyajima, K.; Shiraki, K.; Ando, J.; Kudoh, K.; Nakae, D.; Takahashi, M.; Maekawa, A. Hepatotoxicity and consequently increased cell proliferation are associated with flumequine hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Lett. 1999, 141, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Tatematsu, M.; Takaba, K.; Iwasaki, S.; Ito, N. Target organ specificity of cell proliferation induced by various carcinogens. Toxicol. Pathol. 1993, 21, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanas, S.A.; Jiang, Q.; McMahon, M.; McWalter, G.K.; McLellan, L.I.; Elcombe, C.R.; Henderson, C.J.; Wolf, C.R.; Moffat, G.J.; Itoh, K.; et al. Loss of the Nrf2 transcription factor causes a marked reduction in constitutive and inducible expression of the glutathione S-transferase Gsta1, Gsta2, Gstm1, Gstm2, Gstm3 and Gstm4 genes in the livers of male and female mice. Biochem. J. 2002, 365, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slocum, S.L.; Kensler, T.W. Nrf2: Control of sensitivity to carcinogens. Arch. Toxicol. 2011, 85, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Kamendulis, L.M.; Hocevar, B.A. Oxidative stress and oxidative damage in carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010, 38, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, S.L. Tuberous sclerosis complex and DNA repair. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 685, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saito, B.; Ohashi, T.; Togashi, M.; Koyanagi, T. The study of BBN induced bladder cancer in mice. Influence of Freund complete adjuvant and associated immunological reactions in mice. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1990, 81, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsuzuki, T.; Nakatsu, Y.; Nakabeppu, Y. Significance of error-avoiding mechanisms for oxidative DNA damage in carcinogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunisada, M.; Sakumi, K.; Tominaga, Y.; Budiyanto, A.; Ueda, M.; Ichihashi, M.; Nakabeppu, Y.; Nishigori, C. 8-Oxoguanine formation induced by chronic UVB exposure makes Ogg1 knockout mice susceptible to skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6006–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xiang, Z.; Ma, X. Role of IFN regulatory factor-1 and IL-12 in immunological resistance to pathogenesis of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced T lymphoma. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarchoan, M.; Johnson, B.A., III; Lutz, E.R.; Laheru, D.A.; Jaffee, E.M. Targeting neoantigens to augment antitumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Final Body and Organ Weights | Ogg1−/− | Ogg1+/+ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | G7 | G8 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| Treatment | DMBDD | Control | DMBDD | Control | DMBDD | Control | DMBDD | Control |

| Effective No. of mice | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| No. of surviving animals a (%) | 17(85) | 20(100) | 17(85) | 20(100) | 16(80) | 19(95) | 19(95) | 20(100) |

| Final body weight (g) e | 29.0 ± 3.3 | 30.6 ± 1.9 c | 24.7 ± 1.5 | 25.0 ± 2.6 a | 26.7 ± 2.7 **** | 33.8 ± 2.8 | 23.7 ± 1.6 *** | 26.9 ± 2.5 |

| Organ weights | ||||||||

| Liver (g) | 1.48 ± 0.21 *** | 1.26 ± 0.13 d | 1.07 ± 0.11 **,b | 0.95 ± 0.13 d | 1.45±0.18 ** | 1.64 ± 0.22 | 0.94 ±0.15 **** | 1.13 ± 0.12 |

| Liver (%) | 5.14 ± 0.71 **** | 4.11 ± 0.32 d | 4.36 ± 0.40 ***,a | 3.83 ± 0.38 b | 5.35 ± 0.77 | 4.93 ± 0.68 | 4.02 ± 0.53 | 4.22 ± 0.31 |

| Kidneys (g) | 0.43 ± 0.05 * | 0.39 ± 0.07 d | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.04 b | 0.40 ± 0.05 **** | 0.53 ± 0.11 | 0.28 ± 0.04 ** | 0.34 ± 0.06 |

| Kidneys (%) | 1.51 ± 0.22 ** | 1.28 ± 0.20 c | 1.21 ± 0.07 * | 1.14 ± 0.11 b | 1.50 ± 0.22 | 1.60 ± 0.30 | 1.22 ± 0.15 | 1.27 ±0.17 |

| Spleen (g) | 0.14 ± 0.15 * | 0.06 ± 0.01 d | 0.07 ± 0.02 ** | 0.05 ± 0.01 d | 0.11 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| Spleen (%) | 0.47 ± 0.49 * | 0.20 ± 0.04 b | 0.30 ± 0.08 *** | 0.23 ± 0.03 c | 0.39 ± 0.28 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 0.28 ± 0.05 |

| Lungs (g) | 0.25 ± 0.06 **** | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.04 **** | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.05 **** | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.04 **** | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

| Lungs (%) | 0.90 ± 0.28 **** | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 0.97 ± 0.16 **** | 0.61 ± 0.08 a | 1.00 ± 0.22 **** | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.98 ± 0.18 **** | 0.56 ± 0.08 |

| Incidence in Males (No. Mice (%)) | Ogg1−/− | Ogg1+/+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | G1 | G2 | G5 | G6 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Treatment | DMBDD | Control | DMBDD | Control |

| Effective No. mice | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| No. tumor-bearing mice (%) | 20(100) **** | 1(5) | 17(85) **** | 0 |

| No. tumors/mouse | 5.9 ± 3.5 ****,a | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 2.8 **** | 0 |

| Lung | ||||

| Adenoma | 20(100) ****,a | 1(5) | 14(70) **** | 0 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 7(35) ** | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Total tumors | 20(100) ****,a | 1(5) | 15(75) **** | 0 |

| HPL | 20(100) **** | 1(5) | 20(100) **** | 0 |

| Liver | ||||

| HCA | 4(20) (i) | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Hemangioma | 2(10) | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Hemangiosarcoma | 3(15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total tumors | 5(25) * | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Basophilic PPFs | 2(10) | 0 | 3(15) | 0 |

| Eosinophilic PPFs | 0 | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Mixed type PPFs | 0 | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Kidneys | ||||

| Tubular cell HPL | 5(25) (i) | 1(5) | 2(10) | 1(5) |

| Urinary Bladder | ||||

| Papilloma | 1(5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TCC | 1(5) | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Total tumors | 2(10) | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Simple HPL | 5(25) * | 0 | 5(25) | 1(5) |

| PN HPL | 4(20) (i) | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Colon | ||||

| Adenoma | 4(20) (i) | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1(5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total tumors | 5(25) * | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Small Intestine | ||||

| Adenoma | 3(15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AdCa | 1(5) | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Total tumors | 4(20) (i) | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Forestomach | ||||

| Squamous cell HPL | 14(70) ****,a | 0 | 7(35) ** | 0 |

| Glandular Stomach | ||||

| Adenoma | 1(5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adenomatous cell HPL | 1(5) | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Lymphoma/Leukemia | 3(15) | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Skin/Subcutis | ||||

| Fibrosarcoma | 3(15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Incidence in Females (No. Mice (%)) | Ogg1 −/− | Ogg1 +/+ | ||

| Group | G3 | G4 | G7 | G8 |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Female |

| Treatment | DMBDD | Control | DMBDD | Control |

| Effective No. mice | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| No. tumor-bearing mice (%) | 20(100) ****,b | 0 | 8(40) ** | 0 |

| No. tumors/mouse | 4.6 ± 2.1 ****,b | 0 | 0.7 ± 0.9 ** | 0 |

| Lung | ||||

| Adenoma | 19(95) ****,b | 0 | 12(60) **** | 0 |

| AdCa | 2(10) | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Total tumors | 20(100) ****,b | 0 | 12(60) **** | 0 |

| HPL | 20(100) **** | 1(5) | 17(85) **** | 0 |

| Liver | ||||

| HCA | 4(20) (i) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemangioma | 1(5) | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Hemangiosarcoma | 1(5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total tumors | 5(25) * | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Basophilic PPFs | 1(5) | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Kidneys | ||||

| Renal cell adenoma | 0 | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Tubular cell HPL | 2(10) | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Urinary Bladder | ||||

| TCC | 1(5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Simple HPL | 6(30) | 3(15) | 2(10) | 2(10) |

| PN HPL | 3(15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colon | ||||

| Adenoma | 2(10) | 0 | 4(20) (i) | 0 |

| Small Intestine | ||||

| Adenoma | 1(5) | 0 | 2(10) | 0 |

| Forestomach | ||||

| Squamous cell HPL | 11(55) *** | 1(5) | 8(40) ** | 0 |

| Glandular Stomach | ||||

| AdCa | 1(5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adenomatous cell HPL | 1(5) | 2(10) | 0 | 0 |

| Thyroid | ||||

| Follicular cell Adenoma | 0 | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Lymphoma/Leukemia | 4(20) (i) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| T Cell Lymphoma | 0 | 0 | 1(5) | 0 |

| Adrenals | ||||

| Cortical HPL | 1(5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parameter | Ogg1−/− | Ogg1+/+ | Ogg1−/− | Ogg1+/+ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | G7 | G8 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| Treatment | DMBDD | Control | DMBDD | Control | DMBDD | Control | DMBDD | Control |

| Effective No. mice | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| AST (IU/L) | 88.9 ± 39.7 (i) | 52.3 ± 3.2 | 78.7 ± 14.6 ** | 58.3 ± 5.9 a | 75.1 ± 11.2 ** | 57.3 ± 9.1 | 65.1 ± 12.1 * | 51.9 ± 5.6 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 98.7 ± 82.9 * | 26.9 ± 9.7 | 50.7 ± 15.4 ** | 27.2 ± 7.4 | 61.4 ± 22.8 ** | 32.8 ± 7.9 | 42.0 ± 23.0 * | 22.1 ± 2.8 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 298.6 ± 105.5 | 245.0 ± 53.7 | 535.6 ± 138.3 | 452.4 ± 88.3 | 382.3 ± 93.7 ** | 224.0 ± 35.9 | 472.4 ± 82.2 * | 375.0 ± 93.0 |

| γ-GTP (IU/L) | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 |

| T-protein (g/dl) | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.2 * | 5.3 ± 0.3 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.0 ± 0.5 * | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 ** | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.1 |

| A/G ratio | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 ** | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| T-BiL (mg/dL) | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 154.1 ± 2.7 * | 153.4 ± 1.2 (i) | 152.2 ± 1.6 * | 150.7 ± 1.9 | 154.9 ± 1.7 * | 152.8 ± 1.2 | 153.0 ± 1.7 ** | 150.8 ± 1.4 |

| K (mEq/L) | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 6.6 ± 1.5 | 5.5 ± 0.9 | 5.3 ± 0.8 |

| Cl (mEq/L) | 109.7 ± 3.0 | 109.8 ± 1.8 | 111.0 ± 1.9 | 109.2 ± 2.3 | 111.3 ± 2.0 * | 109.1 ± 1.5 | 112.7 ± 2.3 * | 110.6 ± 2.2 |

| Ca (mEq/L) | 8.8 ± 0.5 a | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 8.7 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.4 | 8.7 ± 0.4 | 8.7 ± 0.3 |

| IP (mEq/L) | 10.3 ± 1.1 | 9.8 ± 1.1 | 9.5 ± 1.8 a | 9.4 ± 2.0 a | 9.5 ± 0.8 | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 7.8 ± 1.4 | 7.4 ± 0.9 |

| T-Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 78.3 ± 21.4 | 87.8 ± 9.1 | 65.3 ± 6.5 | 74.1 ± 17.3 | 78.0 ± 20.5 * | 103.0 ± 29.8 | 59.4 ± 14.6 ** | 100.3 ± 9.6 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 114.0 ± 211.2 | 80.4 ± 32.1 | 33.4 ± 24.7 | 32.3 ± 16.1 | 72.9 ± 25.4 | 68.2 ± 41.3 | 27.1 ± 14.9 | 33.8 ± 16.6 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 35.6 ± 6.0 | 33.4 ± 5.4 | 35.1 ± 4.0 | 32.1 ± 4.3 | 35.3 ± 3.5 | 31.4 ± 4.3 | 31.6 ± 7.2 | 26.3 ± 8.5 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.05 ± 0.02 * | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.03 * | 0.03 ± 0.02 b | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kakehashi, A.; Ishii, N.; Okuno, T.; Fujioka, M.; Gi, M.; Wanibuchi, H. Enhanced Susceptibility of Ogg1 Mutant Mice to Multiorgan Carcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1801. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms18081801

Kakehashi A, Ishii N, Okuno T, Fujioka M, Gi M, Wanibuchi H. Enhanced Susceptibility of Ogg1 Mutant Mice to Multiorgan Carcinogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(8):1801. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms18081801

Chicago/Turabian StyleKakehashi, Anna, Naomi Ishii, Takahiro Okuno, Masaki Fujioka, Min Gi, and Hideki Wanibuchi. 2017. "Enhanced Susceptibility of Ogg1 Mutant Mice to Multiorgan Carcinogenesis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 8: 1801. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms18081801