A Biostimulant Obtained from the Seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum Protects Arabidopsis thaliana from Severe Oxidative Stress

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

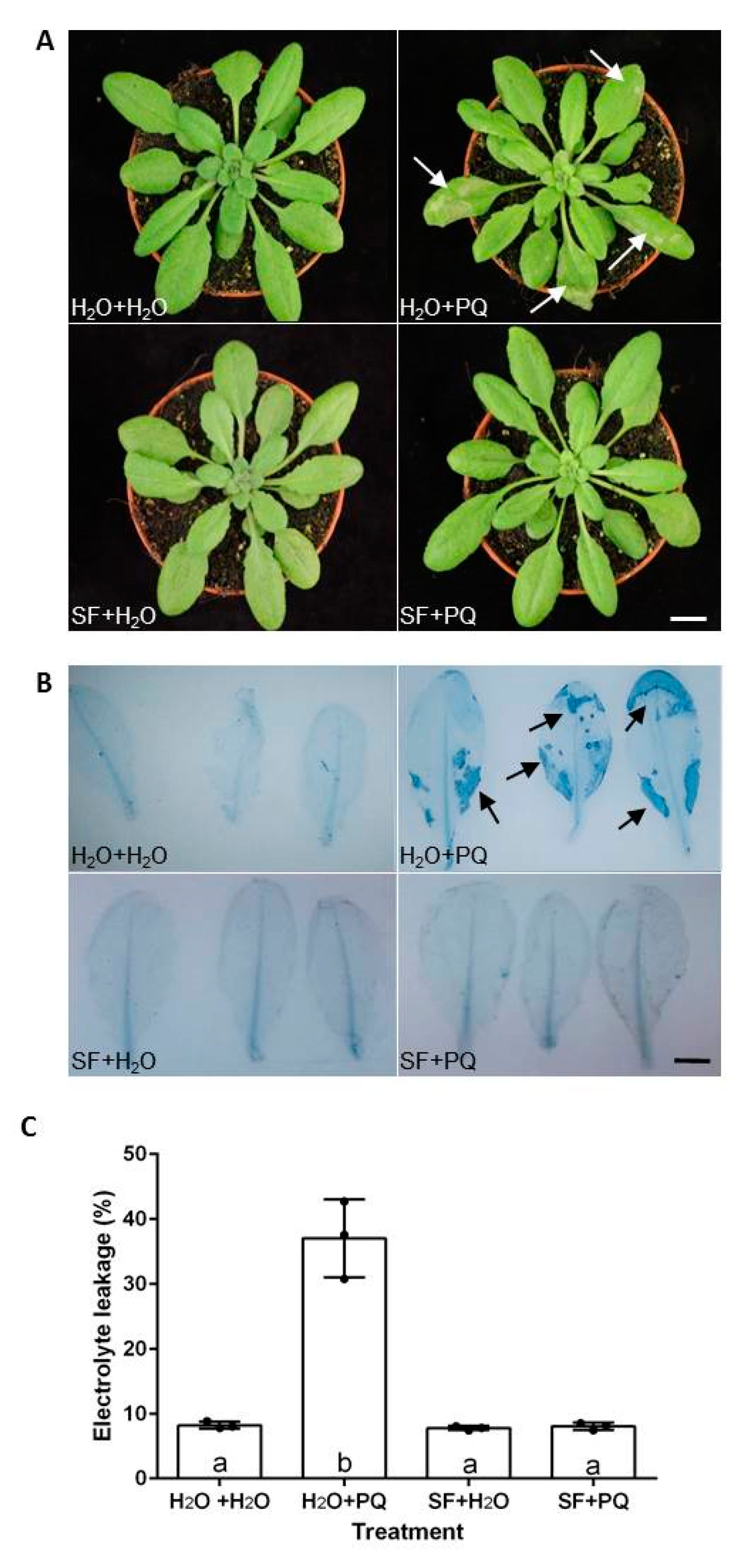

2.1. SF Protects Arabidopsis from Oxidative Stress

2.2. RNA-Seq Identifies Genes and Pathways Associated with SF-Induced Oxidative Stress Protection

2.2.1. Cluster Analysis of DEGs

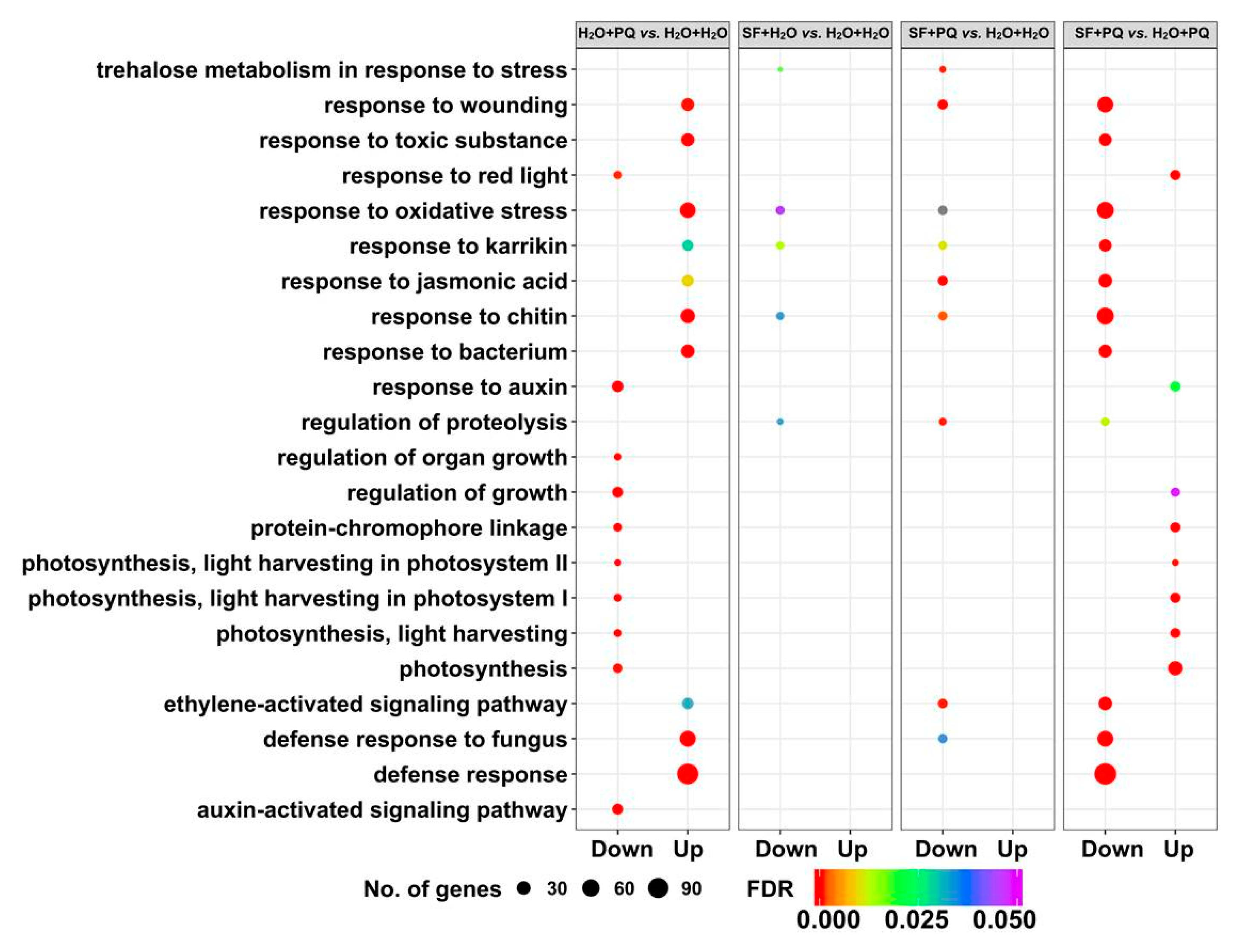

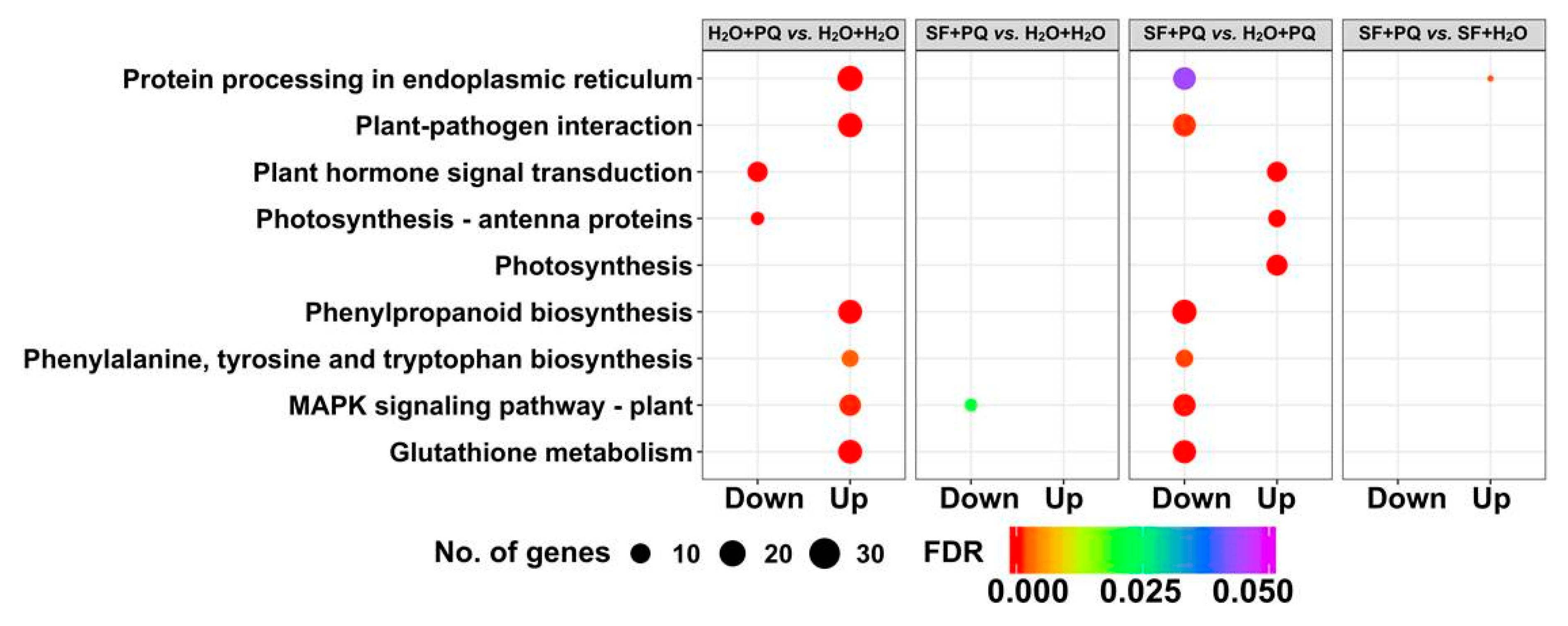

2.2.2. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

2.2.3. Annotation of Genes Induced by SF for Oxidative Stress Protection

ROS-Responsive Genes, Programmed Cell Death, and Senescence

Detoxification of PQ-induced ROS

Photosynthetic Genes

Carbohydrate Metabolism

Growth and Hormone Signaling

Autophagy

Lipid Metabolism

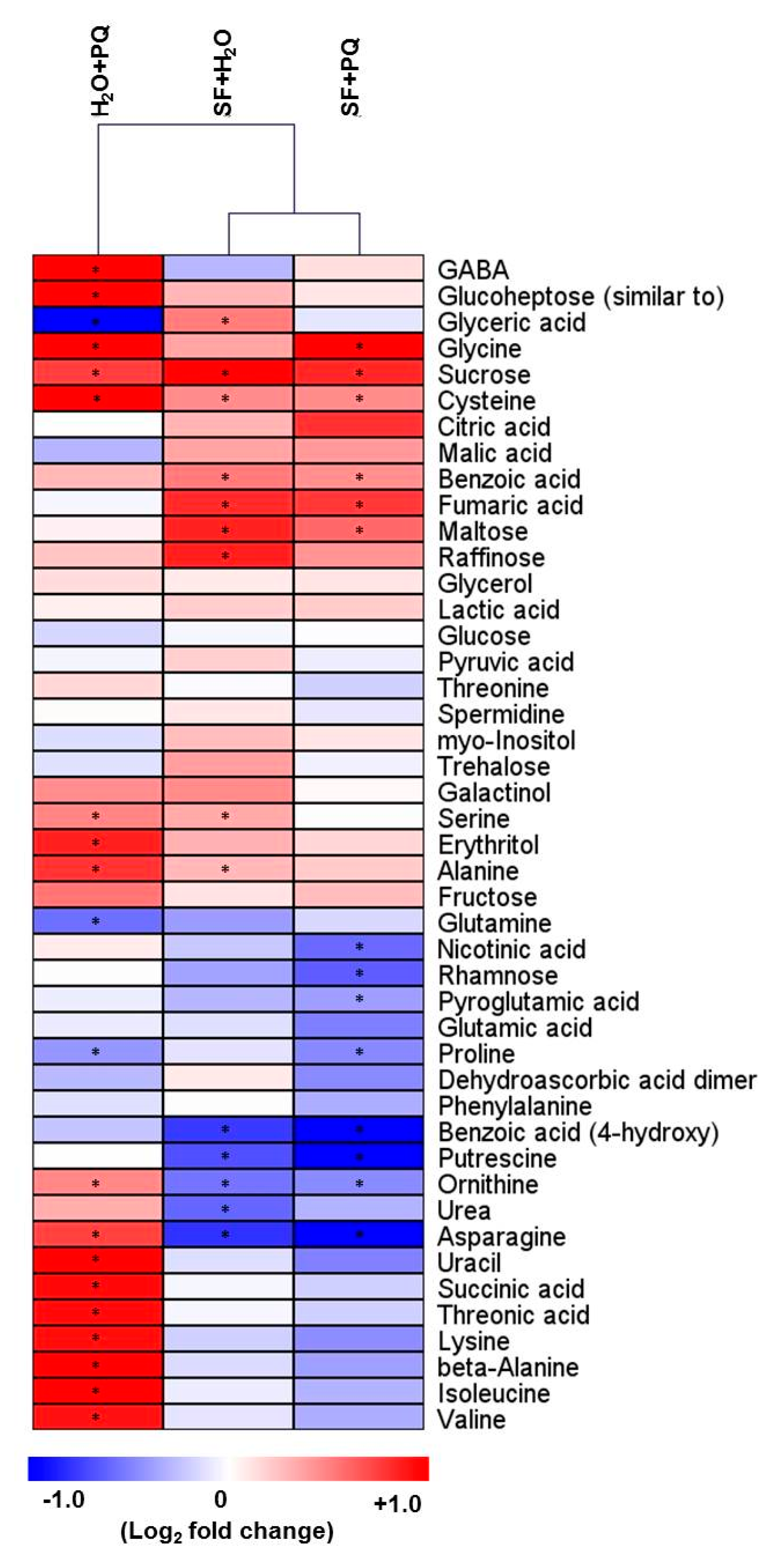

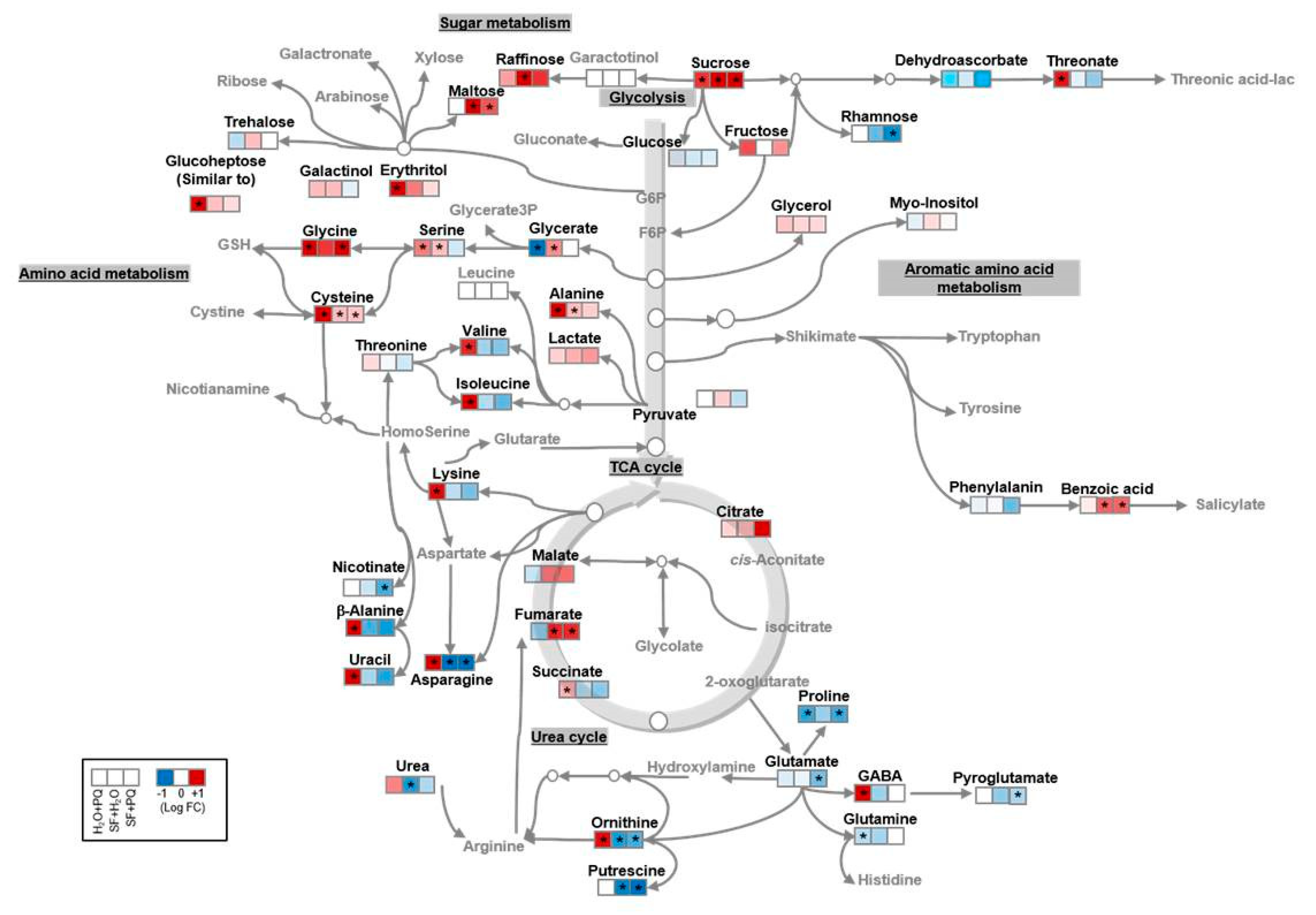

2.3. Metabolome Reconfiguration Induced by SF for Oxidative Stress Protection

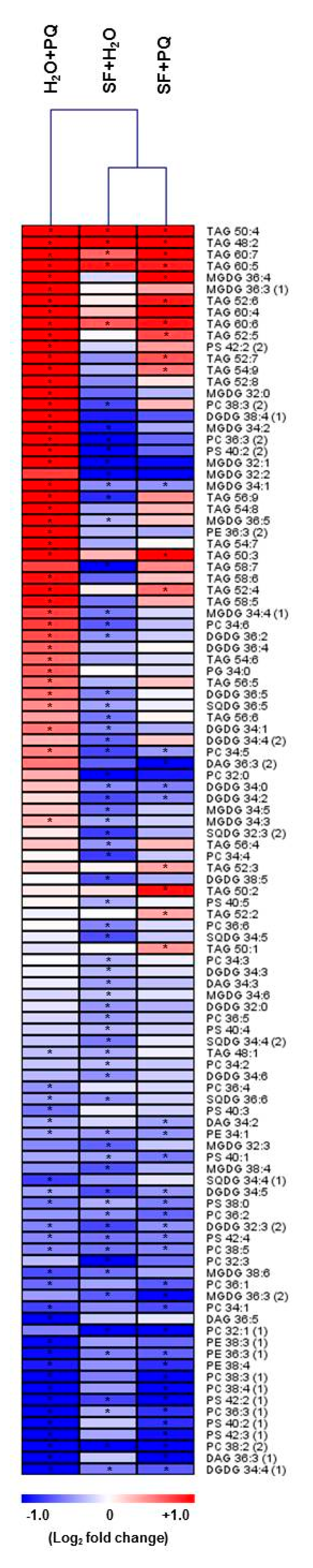

2.4. Lipidome Level Changes Induced by SF for Oxidative Stress Protection

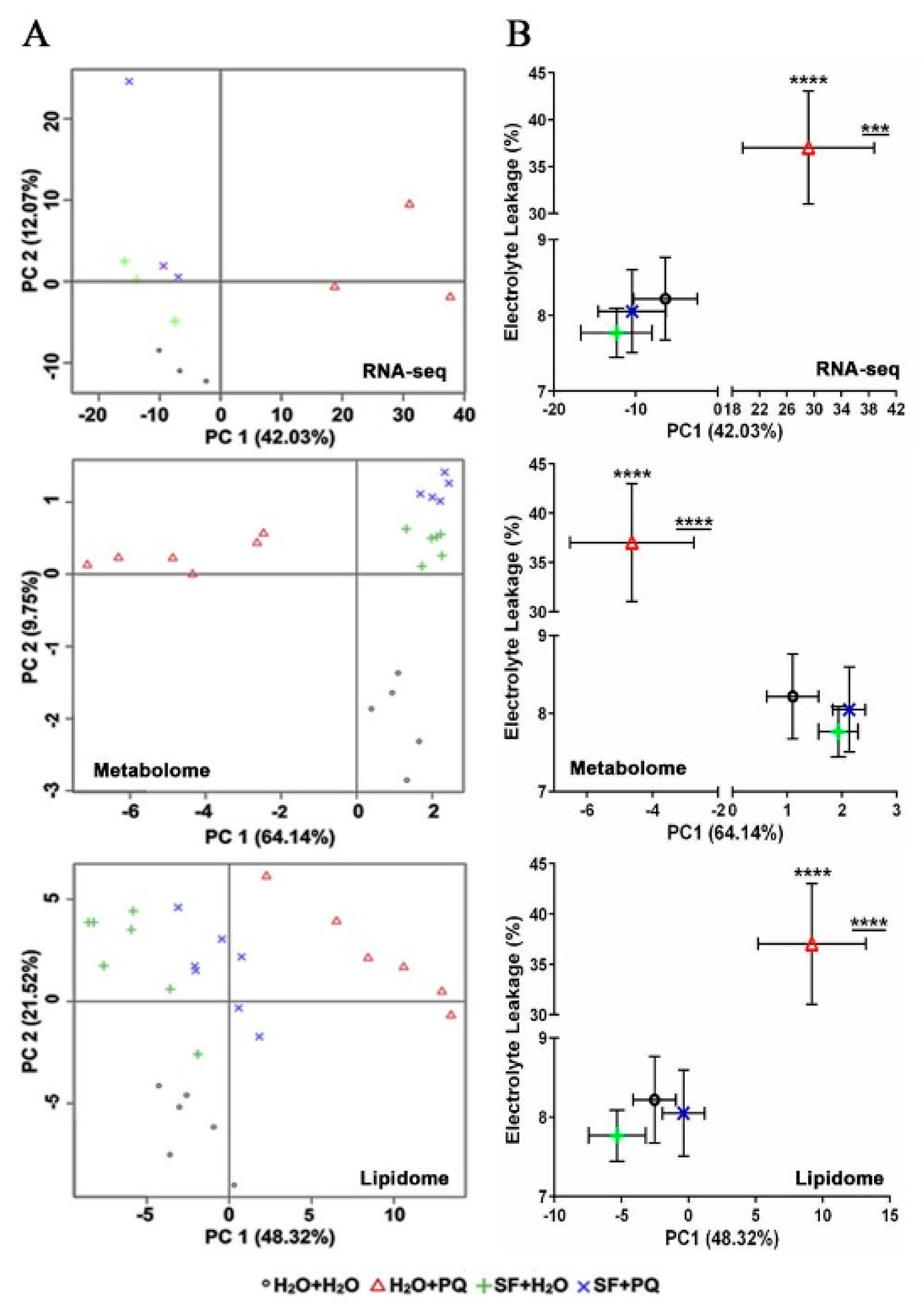

2.5. Assessment of the Relationship between Molecular and Phenotypic Changes Induced by SF

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material, Stress Treatments, and RNA Extraction

3.2. Electrolyte Leakage Measurements and Trypan Blue Staining

3.3. Transcriptome Sequencing and Data Analysis

3.4. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis of Primary Metabolites

3.5. Lipid Profiling

3.6. Analysis of Differential Behavior of Metabolites and Lipids

3.7. Principal Component Analysis

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmadi, H.; Corso, M.; Weber, M.; Verbruggen, N.; Clemens, S. CAX1 suppresses Cd-induced generation of reactive oxygen species in Arabidopsis halleri. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 2435–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassia, R.; Nocioni, M.; Correa-Aragunde, N.; Lamattina, L. Climate change and the impact of greenhouse gasses: CO2 and NO, friends and foes of plant oxidative stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, T.K.; Anderson, M.D.; Martin, B.A.; Stewart, C.R. Evidence for chilling-induced oxidative stress in maize seedlings and a regulatory role for hydrogen peroxide. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, T.K.; Anderson, M.D.; Stewart, C.R. Acclimation, hydrogen peroxide, and abscisic acid protect mitochondria against irreversible chilling injury in maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1994, 105, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, F.J.; Jin, C.W.; Liu, W.J.; Zhang, Y.S.; Lin, X.Y. Pretreatment with H2O2 alleviates aluminum-induced oxidative stress in wheat seedlings. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gechev, T.S.; Hille, J. Molecular basis of plant stress. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 3161–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, R.; Sun, S.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Liang, Y.; An, F.; Li, C.; Dong, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. The Arabidopsis PARAQUAT RESISTANT2 gene encodes an S-nitrosoglutathione reductase that is a key regulator of cell death. Cell Res. 2009, 19, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gechev, T.S.; Van Breusegem, F.; Stone, J.M.; Denev, I.; Laloi, C. Reactive oxygen species as signals that modulate plant stress responses and programmed cell death. BioEssays 2006, 28, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mu, J.; Bai, J.; Fu, F.; Zou, T.; An, F.; Zhang, J.; Jing, H.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; et al. PARAQUAT RESISTANT1, a golgi-localized putative transporter protein, is involved in intracellular transport of paraquat. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, C.; Cai, X.T.; Du, J.; Zhao, T.L.; Wang, P.F.; Zhao, P.X.; Liu, R.; Xie, Q.; Cao, X.F.; Xiang, C. PARAQUAT TOLERANCE3 is an E3 ligase that switches off activated oxidative response by targeting histone-modifying PROTEIN METHYLTRANSFERASE4b. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sukrong, S.; Yun, K.Y.; Stadler, P.; Kumar, C.; Facciuolo, T.; Moffatt, B.A.; Falcone, D.L. Improved growth and stress tolerance in the Arabidopsis oxt1 mutant triggered by altered adenine metabolism. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 1310–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xi, J.; Xu, P.; Xiang, C. Loss of AtPDR11, a plasma membrane-localized ABC transporter, confers paraquat tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2012, 69, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Addepalli, B.; Yun, K.Y.; Hunt, A.G.; Xu, R.; Rao, S.; Li, Q.Q.; Falcone, D.L. A polyadenylation factor subunit implicated in regulating oxidative signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pulido, P.; Llamas, E.; Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. Both Hsp70 chaperone and Clp protease plastidial systems are required for protection against oxidative stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2017, 12, e1290039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, S.; Rampuria, S.; Reddy, A.R.; Kirti, P.B. Ectopic expression of an atypical hydrophobic group 5 LEA protein from wild peanut, Arachis diogoi confers abiotic stress tolerance in tobacco. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gechev, T.S.; Gadjev, I.; Van Breusegem, F.; Inzé, D.; Dukiandjiev, S.; Toneva, V.; Minkov, I. Hydrogen peroxide protects tobacco from oxidative stress by inducing a set of antioxidant enzymes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafez, Y.M.; Bacsó, R.; Király, Z.; Künstler, A.; Király, L. Up-regulation of antioxidants in tobacco by low concentrations of H2O2 suppresses necrotic disease symptoms. Phytopathology 2012, 102, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Gutiérrez, R.; Mora-Herrera, M.E.; López-Delgado, H.A. Exogenous H2O2 in phytoplasma-infected potato plants promotes antioxidant activity and tuber production under drought conditions. Am. J. Potato Res. 2012, 89, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskova, I.; Todorova, D.; Alexieva, V.; Ivanov, S.; Sergiev, I. Effect of exogenous hydrogen peroxide on enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants in leaves of young pea plants treated with paraquat. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 57, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Romero, M.T.; López-Delgado, H.A. Ameliorative effects of hydrogen peroxide, ascorbate and dehydroascorbate in Solanum tuberosum infected by phytoplasma. Am. J. Potato Res. 2009, 86, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obata, T.; Fernie, A.R. The use of metabolomics to dissect plant responses to abiotic stresses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 3225–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dautel, S.E.; Kyle, J.E.; Clair, G.; Sontag, R.L.; Weitz, K.K.; Shukla, A.K.; Nguyen, S.N.; Kim, Y.M.; Zink, E.M.; Luders, T.; et al. Lipidomics reveals dramatic lipid compositional changes in the maturing postnatal lung. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Durgud, M.; Gupta, S.; Ivanov, I.; Omidbakhshfard, M.A.; Benina, M.; Alseekh, S.; Staykov, N.; Hauenstein, M.; Dijkwel, P.P.; Hörtensteiner, S.; et al. Molecular mechanisms preventing senescence in response to prolonged darkness in a desiccation-tolerant plant. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 1319–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jannin, L.; Arkoun, M.; Etienne, P.; Laîné, P.; Goux, D.; Garnica, M.; Fuentes, M.; Francisco, S.S.; Baigorri, R.; Cruz, F.; et al. Brassica napus growth is promoted by Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol. seaweed extract: Microarray analysis and physiological characterization of N, C, and S metabolisms. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 32, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Rayirath, U.P.; Subramanian, S.; Jithesh, M.N.; Rayorath, P.; Hodges, D.M.; Critchley, A.T.; Craigie, J.S.; Norrie, J.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants of plant growth and development. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Synergistic biostimulatory action: Designing the next generation of plant biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in plant science: A global perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, H.S.S.; Fleming, C.; Selby, C.; Rao, J.R.; Martin, T. Plant biostimulants: A review on the processing of macroalgae and use of extracts for crop management to reduce abiotic and biotic stresses. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinan, K.; Sujeeth, N.; Copeland, R.; Jones, P.; O’brien, N.; Sharma, H.; Prouteau, P.F.J.; O’Sullivan, J. Discrete roles for extracts of Ascophyllum nodosum in enhancing plant growth and tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses. In: World Congress on the Use of Biostimulants in Agriculture. Acta Hortic. 2013, 1009, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, E.; Van Oosten, M.J.; Silletti, S.; Raimondi, G.; dell’Aversana, E.; Carillo, P.; Maggio, A. Ascophyllum nodosum-based algal extracts act as enhancers of growth, fruit quality, and adaptation to stress in salinized tomato plants. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2675–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Scartazza, A.; Gresta, F.; Loreti, E.; Biasone, A.; Di Tommaso, D.; Piaggesi, A.; Perata, P. Ascophyllum nodosum seaweed extract alleviates drought stress in Arabidopsis by affecting photosynthetic performance and related gene expression. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shukla, P.S.; Mantin, E.G.; Adil, M.; Bajpai, S.; Critchley, A.T.; Prithiviraj, B. Ascophyllum nodosum-based biostimulants: Sustainable applications in agriculture for the stimulation of plant growth, stress tolerance, and disease management. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, N.; Bhalla, P.; Singh, M. Transcriptome-wide profiling and expression analysis of transcription factor families in a liverwort, Marchantia polymorpha. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goñi, O.; Quille, P.; O’Connell, S. Ascophyllum nodosum extract biostimulants and their role in enhancing tolerance to drought stress in tomato plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 126, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, P.S.; Borza, T.; Critchley, A.T.; Hiltz, D.; Norrie, J.; Prithiviraj, B. Ascophyllum nodosum extract mitigates salinity stress in Arabidopsis thaliana by modulating the expression of miRNA involved in stress tolerance and nutrient acquisition. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qureshi, M.K.; Sujeeth, N.; Gechev, T.S.; Hille, J. The zinc finger protein ZAT11 modulates paraquat-induced programmed cell death in Arabidopsis thaliana. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.B.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, S.Y. AtERF15 is a positive regulator of ABA response. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelim, L.; Akiyoshi, N.; Tan, T.T.; Ihara, A.; Yamaguchi, M.; Hirano, K.; Matsuoka, M.; Demura, T.; Ohtani, M. Arabidopsis Group IIId ERF proteins positively regulate primary cell wall-type CESA genes. J. Plant. Res. 2019, 132, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeff, M.; Straub, D.; Eguen, T.; Dolde, U.; Rodrigues, V.; Brandt, R.; Wenkel, S. MicroProtein-mediated recruitment of CONSTANS into a TOPLESS trimeric complex represses flowering in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, G.; Pan, Y.; Lei, J.; Zhu, Y.X. Molecular cloning, phylogenetic analysis, expressional profiling and in vitro studies of TINY2 from Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 38, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gong, D.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J.K. Constitutive activation and transgenic evaluation of the function of an Arabidopsis PKS protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 42088–42096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dhonukshe, P.; Huang, F.; Galvan-Ampudia, C.S.; Mähönen, A.P.; Kleine-Vehn, J.; Xu, J.; Quint, A.; Prasad, K.; Friml, J.; Scheres, B.; et al. Plasma membrane-bound AGC3 kinases phosphorylate PIN auxin carriers at TPRXS (N/S) motifs to direct apical PIN recycling. Development 2010, 137, 3245–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duan, K.; Yi, K.; Dang, L.; Huang, H.; Wu, W.; Wu, P. Characterization of a sub-family of Arabidopsis genes with the SPX domain reveals their diverse functions in plant tolerance to phosphorus starvation. Plant J. 2008, 54, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gechev, T.S.; Ferwerda, M.A.; Mehterov, N.; Laloi, C.; Qureshi, M.K.; Hille, J. Arabidopsis AAL-toxin-resistant mutant atr1 shows enhanced tolerance to programmed cell death induced by reactive oxygen species. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 375, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saibo, N.J.M.; Lourenço, T.; Oliveira, M.M. Transcription factors and regulation of photosynthetic and related metabolism under environmental stresses. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gadjev, I.; Vanderauwera, S.; Gechev, T.S.; Laloi, C.; Minkov, I.N.; Shulaev, V.; Apel, K.; Inzé, D.; Mittler, R.; Van Breusegem, F. Transcriptomic footprints disclose specificity of reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehterov, N.; Balazadeh, S.; Hille, J.; Toneva, V.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. Oxidative stress provokes distinct transcriptional responses in the stress-tolerant atr7 and stress-sensitive loh2 Arabidopsis thaliana mutants as revealed by multi-parallel quantitative real-time PCR analysis of ROS markers and antioxidant genes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 59, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benina, M.; Ribeiro, D.M.; Gechev, T.S.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Schippers, J.H.M. A cell type-specific view on the translation of mRNAs from ROS-responsive genes upon paraquat treatment of Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.H.M.; Giraud, E.; Uggalla, V.; Lister, R.; Clifton, R.; Glen, A.; Thirkettle-Watts, D.; Van Aken, O.; Whelan, J. Identification of regulatory pathways controlling gene expression of stress-responsive mitochondrial proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1858–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrov, V.; Hille, J.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. ROS-mediated abiotic stress-induced programmed cell death in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ge, X.; Dietrich, C.; Matsuno, M.; Li, G.; Berg, H.; Xia, Y. An Arabidopsis aspartic protease functions as an anti-cell-death component in reproduction and embryogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2005, 6, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiao, D.; Cui, Y.; Xu, F.; Xu, X.; Gao, G.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, D.; Wang, N.N. SENESCENCE-SUPPRESSED PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE directly interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE and negatively regulates leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1275–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kamranfar, I.; Xue, G.; Tohge, T.; Sedaghatmehr, M.; Fernie, A.R.; Balazadeh, S.; Mueller-Roeber, B. Transcription factor RD26 is a key regulator of metabolic reprogramming during dark-induced senescence. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, S.; Gao, J.; Yao, L.; Ren, G.; Zhu, X.; Gao, S.; Qiu, K.; Zhou, X.; Kuai, B. The role of ANAC072 in the regulation of chlorophyll degradation during age- and dark-induced leaf senescence. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 1729–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, J.H.M.; Jing, H.-C.; Hille, J.; Dijkwel, P.P. Developmental and hormonal control of leaf senescence. In Senescence Processes in Plants; Gan, S., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, T.; Yokoyama, E.; Inoue, K.; Sakurai, H. The sites of electron donation of Photosystem I to methyl viologen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1990, 1015, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Váradi, G.; Darkó, E.; Lehoczki, E. Changes in the xanthophyll cycle and fluorescence quenching indicate light-dependent early events in the action of paraquat and the mechanism of resistance to paraquat in Erigeron canadensis (L.) cronq. Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekmekci, Y.; Terzioglu, S. Effects of oxidative stress induced by paraquat on wild and cultivated wheats. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2005, 83, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoudt, N.; Vandenhove, H.; Horemans, N.; Wannijn, J.; Bujanic, A.; Vangronsveld, J.; Cuypers, A. Study of oxidative stress related responses induced in Arabidopsis thaliana following mixed exposure to uranium and cadmium. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Hecker, A.G.; Hauser, B.A. The APX4 locus regulates seed vigor and seedling growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2014, 239, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Mao, Y.; Lai, D.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, T.; Shen, W. Roles of NIA/NR/NOA1-dependent nitric oxide production and HY1 expression in the modulation of Arabidopsis salt tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3045–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bu, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, X.; Takano, T.; Liu, S. Overexpression of AtOxR gene improves abiotic stresses tolerance and vitamin C content in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Biotechnol. 2016, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akram, N.A.; Shafiq, F.; Ashraf, M. Ascorbic Acid-A Potential Oxidant Scavenger and Its Role in Plant Development and Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, N.A.; Gill, S.S.; Gill, R.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Duarte, A.C.; Pereira, E.; Tuteja, N. Metal/metalloid stress tolerance in plants: Role of ascorbate, its redox couple, and associated enzymes. Protoplasma 2014, 251, 1265–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tullio, M.; Guether, M.; Balestrini, R. Ascorbate oxidase is the potential conductor of a symphony of signaling pathways. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e23213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horemans, N.; Foyer, C.H.; Asard, H. Transport and action of ascorbate at the plant plasma membrane. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.C.J.; Margulies, E.H.; Tullius, T.D. The relationship between fine scale DNA structure, GC content, and functional elements in 1% of the human genome. Genome Inform. 2008, 20, 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nechushtai, R.; Conlan, A.R.; Harir, Y.; Song, L.; Yogev, O.; Eisenberg-Domovich, Y.; Livnah, O.; Michaeli, D.; Rosen, R.; Ma, V.; et al. Characterization of Arabidopsis NEET reveals an ancient role for NEET proteins in iron metabolism. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2139–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asada, K. Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Busi, R.; Vila-Aiub, M.M.; Powles, S.B. Genetic control of a cytochrome P450 metabolism-based herbicide resistance mechanism in Lolium rigidum. Heredity 2011, 106, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Höfer, R.; Boachon, B.; Renault, H.; Gavira, C.; Miesch, L.; Iglesias, J.; Ginglinger, J.F.; Allouche, L.; Miesch, M.; Grec, S.; et al. Dual function of the cytochrome P450 CYP76 family from Arabidopsis thaliana in the metabolism of monoterpenols and phenylurea herbicides. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giacomelli, L.; Rudella, A.; van Wijk, K.J. High light response of the thylakoid proteome in Arabidopsis wild type and the ascorbate-deficient mutant vtc2-2. A comparative proteomics study. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pattanayak, G.K.; Tripathy, B.C. Overexpression of protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase C regulates oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishizawa, A.; Yabuta, Y.; Shigeoka, S. Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markakis, M.; De Cnodder, T.; Lewandowski, M.; Simon, D.; Boron, A.; Balcerowicz, D.; Doubbo, T.; Taconnat, L.; Renou, J.-P.; Höfte, H.; et al. Identification of genes involved in the ACC-mediated control of root cell elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urbanowicz, B.R.; Bennett, A.B.; del Campillo, E.; Catala, C.; Hayashi, T.; Henrissat, B.; Höfte, H.; McQueen-Mason, S.J.; Patterson, S.E.; Shoseyov, O.; et al. Structural organization and a standardized nomenclature for plant endo-1,4-β-glucanases (cellulases) of glycosyl hydrolase family 9. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 1693–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, R.; Cui, D.; Ye, Z.-H. Xyloglucan O-acetyltransferases from Arabidopsis thaliana and Populus trichocarpa catalyze acetylation of fucosylated galactose residues on xyloglucan side chains. Planta 2018, 248, 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafisi, M.; Stranne, M.; Fimognari, L.; Atwell, S.; Martens, H.J.; Pedas, P.R.; Hansen, S.F.; Nawrath, C.; Scheller, H.V.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; et al. Acetylation of cell wall is required for structural integrity of the leaf surface and exerts a global impact on plant stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Contento, A.L.; Nguyen, P.Q.; Bassham, D.C. Degradation of oxidized proteins by autophagy during oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Cheng, Y.; Fan, B.; Yu, J.-Q.; Chen, Z. Arabidopsis sigma factor binding proteins are activators of the WRKY33 transcription factor in plant defense. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3824–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.-Q.; Chen, Z. Role and regulation of autophagy in heat stress responses of tomato plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Q.; Soulay, F.; Saudemont, B.; Elmayan, T.; Marmagne, A.; Masclaux-Daubresse, C. Overexpression of ATG8 in Arabidopsis stimulates autophagic activity and increases nitrogen remobilization efficiency and grain filling. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 60, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olenieva, V.; Lytvyn, D.; Yemets, A.; Bergounioux, C.; Blume, Y. Tubulin acetylation accompanies autophagy development induced by different abiotic stimuli in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Biol. Int. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, J.; Lorenc-Kukula, K.; Singh, V.; Reese, J.; Jander, G.; Shah, J. Antibiosis against the green peach aphid requires the Arabidopsis thaliana MYZUS PERSICAE-INDUCED LIPASE1 gene. Plant J. 2010, 64, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Huang, Y.; Xi, J.; Cao, M.; Ni, W.; Chen, X.; Zhu, J.K.; Oliver, D.J.; Xiang, C.B. Functional gene-mining for salt-tolerance genes with the power of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008, 56, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, J.; Yu, L.; Xu, C. A central role for triacylglycerol in membrane lipid breakdown, fatty acid β-oxidation, and plant survival under extended darkness. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Ascorbate and glutathione: The heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehmann, M.; Schwarzländer, M.; Obata, T.; Sirikantaramas, S.; Burow, M.; Olsen, C.E.; Tohge, T.; Frickler, M.D.; Møller, B.L.; Fernie, A.R.; et al. The metabolic response of Arabidopsis roots to oxidative stress is distinct from that of heterotrophic cells in culture and highlights a complex relationship between the levels of transcripts, metabolites, and flux. Mol. Plant 2009, 2, 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noctor, G.; Lelarge-Trouverie, C.; Mhamdi, A. The metabolomics of oxidative stress. Phytochemistry 2015, 112, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Rui, B.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.; Yi, Y.; Wen, H.; Zheng, H.; Wu, J.; Shi, Y. Metabolic flux ratio analysis and multi-objective optimization revealed a globally conserved and coordinated metabolic response of E. coli to paraquat-induced oxidative stress. Mol. BioSyst. 2013, 9, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fu, X.; Wei, Q.; Grierson, D.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Dong, F.; Yang, Z. Dual mechanisms regulating glutamate decarboxylases and accumulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid in tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves exposed to multiple stresses. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bouché, N.; Fromm, H. GABA in plants: Just a metabolite? Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bown, A.W.; Shelp, B.J. Plant GABA: Not Just a Metabolite. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Balazadeh, S.; Tohge, T.; Erban, A.; Giavalisco, P.; Kopka, J.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Fernie, A.F.; Hoefgen, R. Comprehensive dissection of spatiotemporal metabolic shifts in primary, secondary, and lipid metabolism during developmental senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1290–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Araújo, W.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Nikoloski, Z.; Sweetlove, L.J.; Fernie, A.R. Metabolic control and regulation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle in photosynthetic and heterotrophic plant tissues. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zell, M.B.; Fahnenstich, H.; Maier, A.; Saigo, M.; Voznesenskaya, E.V.; Edwards, G.E.; Andreo, C.; Schleifenbaum, F.; Zell, C.; Drincovich, M.F.; et al. Analysis of Arabidopsis with highly reduced levels of malate and fumarate sheds light on the role of these organic acids as storage carbon molecules. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, K.J.; Shah, J.K.; Brotman, Y.; Jahnke, K.; Willmitzer, L.; Kaiser, W.M.; Bauwe, H.; Igamberdiev, A.U. Inhibition of aconitase by nitric oxide leads to induction of the alternative oxidase and to a shift of metabolism towards biosynthesis of amino acids. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maeda, H.; Song, W.; Sage, T.L.; DellaPenna, D. Tocopherols play a crucial role in low-temperature adaptation and phloem loading in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2710–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, F.; Guy, C.L. β-amylase induction and the protective role of maltose during temperature shock. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 1674–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okazaki, Y.; Saito, K. Roles of lipids as signaling molecules and mitigators during stress response in plants. Plant J. 2014, 79, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, V.; Andosch, A.; Geretschläger, A.; Affenzeller, M.; Lütz-Meindl, U. Carbon starvation induces lipid degradation via autophagy in the model alga Micrasterias. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 208, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, H.H.; Scharnewski, M.; Feussner, K.; Feussner, I.; Flugge, U.I.; Fulda, M.; Gierth, M. The ABC transporter PXA1 and peroxisomal β-oxidation are vital for metabolism in mature leaves of Arabidopsis during extended darkness. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2733–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koch, E.; Slusarenko, A. Arabidopsis is susceptible to infection by a downy mildew fungus. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopylova, E.; Noé, L.; Touzet, H. SortMeRNA: Fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3211–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, N.L.; Pimentel, H.; Melsted, P.; Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Krishnakumar, V.; Chan, A.P.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Schobel, S.; Town, C.D. Araport11: A complete reannotation of the Arabidopsis thaliana reference genome. Plant J. 2017, 89, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, M.D.; Oshlack, A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolde, R. Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps, R package Version 1.0.8; 2015. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lisec, J.; Schauer, N.; Kopka, J.; Willmitzer, L.; Fernie, A.R. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry-based metabolite profiling in plants. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luedemann, A.; von Malotky, L.; Erban, A.; Kopka, J. TagFinder: Preprocessing software for the fingerprinting and the profiling of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry based metabolome analyses. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 860, 255–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kopka, J.; Schauer, N.; Krueger, S.; Birkemeyer, C.; Usadel, B.; Bergmüller, E.; Dörmann, P.; Weckwerth, W.; Gibon, Y.; Stitt, M.; et al. [email protected]: The Golm Metabolome Database. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernie, A.R.; Aharoni, A.; Willmitzer, L.; Stitt, M.; Tohge, T.; Kopka, J.; Carroll, A.J.; Saito, K.; Fraser, P.D.; DeLuca, V. Recommendations for reporting metabolite data. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 2477–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giavalisco, P.; Li, Y.; Matthes, A.; Eckhardt, A.; Hubberten, H.-M.; Hesse, H.; Segu, S.; Hummel, J.; Köhl, K.; Willmitzer, L. Elemental formula annotation of polar and lipophilic metabolites using 13C, 15N and 34S isotope labelling, in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry. Plant J. 2011, 68, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldana, C.; Li, Y.; Leisse, A.; Zhang, Y.; Bartholomaeus, L.; Fernie, A.R.; Willmitzer, L.; Giavalisco, P. Systemic analysis of inducible target of rapamycin mutants reveal a general metabolic switch controlling growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2013, 73, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, G.K. Limma: Linear models for microarray data. In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Stacklies, W.; Redestig, H.; Scholz, M.; Walther, D.; Selbig, J. PcaMethods—A bioconductor package providing PCA methods for incomplete data. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1164–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average TMM Values | Annotation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | H2O + H2O | H2O + PQ | SF + H2O | SF + PQ | Gene Name | Description/Function |

| ROS Inducible/Marker genes | ||||||

| AT2G21640 | 19.63 | 97.21 | 16.99 | 20.09 | Marker for oxidative stress response protein | |

| AT2G43510 | 64.24 | 214.79 | 40.04 | 47.11 | TI1 | Trypsin inhibitor, ROS marker |

| AT1G57630 | 4.07 | 76.13 | 4.36 | 4.51 | Toll-Interleukin-Resistance (TIR) domain family protein | |

| AT1G19020 | 36.57 | 247.44 | 26.24 | 33.40 | CDP-diacylglycerol-glycerol-3-phosphate 3-phosphatidyltransferase, ROS marker | |

| AT1G05340 | 8.55 | 83.32 | 6.72 | 5.41 | Cysteine-rich stress protein, ROS marker | |

| ROS-Dependent PCD and Senescence | ||||||

| AT4G25110 | 1.75 | 6.47 | 2.07 | 2.99 | MC2 | Metacaspase 2 |

| AT1G16420 | 0.15 | 5.83 | 0.37 | 0.47 | MC8 | Metacaspase 8 |

| AT5G02190 | 2.78 | 2.35 | 7.33 | 8.40 | PSC1 | Promotion of cell survival 1 |

| AT5G02760 | 11.95 | 3.34 | 24.69 | 16.34 | SSPP | Senescence-suppressed protein phosphatase |

| AT4G27410 | 73.77 | 100.20 | 27.15 | 22.12 | RD26 | NAC (No Apical Meristem) domain transcriptional regulator superfamily protein |

| AT2G29350 | 31.09 | 395.89 | 19.27 | 16.05 | SAG13 | Senescence-associated gene 13 |

| ROS Detoxification | ||||||

| AT4G25100 | 459.32 | 277.99 | 664.81 | 715.19 | FSD1 | Fe superoxide dismutase 1 |

| AT4G09010 | 378.15 | 197.56 | 405.53 | 403.35 | APX4 | Ascorbate peroxidase 4 |

| AT5G57345 | 207.99 | 168.40 | 323.34 | 337.82 | OXR | Transmembrane OXR protein |

| AT4G39800 | 90.77 | 59.99 | 143.09 | 125.49 | MIPS1 | Myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase 1 |

| AT5G21100 | 23.74 | 13.69 | 30.65 | 24.71 | AO | Plant L-ascorbate oxidase |

| AT5G51720 | 90.38 | 74.87 | 122.85 | 149.99 | NEET | 2 iron, 2 sulfur cluster binding protein |

| AT2G45560 | 43.67 | 26.91 | 67.23 | 67.88 | CYP76C1 | Cytochrome P450 family 76C, polypeptide 1 |

| AT2G46660 | 1.07 | 1.12 | 2.12 | 2.39 | CYP78A6 | Cytochrome P450, family 78A, polypeptide 6 |

| AT3G26310 | 7.03 | 4.62 | 11.01 | 9.27 | CYP71B35 | Cytochrome P450, family 71B, polypeptide35 |

| AT4G12320 | 32.62 | 28.68 | 66.06 | 74.88 | CYP706A6 | Cytochrome P450, family 706A, polypeptide6 |

| Photosynthesis | ||||||

| AT5G38420 | 1223.01 | 567.26 | 1376.75 | 1518.00 | RBCS2B | RuBisCO small chain |

| AT3G27690 | 799.90 | 303.31 | 1142.16 | 1032.88 | LHCB2.3 | Photosystem II LHC protein 2.3 |

| AT1G51400 | 1851.61 | 886.74 | 2086.64 | 2069.37 | Photosystem II 5 kD protein | |

| AT3G08940 | 3027.19 | 1449.15 | 3533.29 | 3026.97 | LHCB4.2 | Light harvesting complex photosystem II |

| AT3G63160 | 2922.20 | 1632.49 | 3304.18 | 3817.24 | OEP6 | Outer envelope membrane protein |

| AT3G27690 | 799.9 | 303.31 | 1142.16 | 1032.88 | LHCB2.4 | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein 2.4 |

| AT2G34430 | 3293.32 | 1182.9 | 3677.36 | 2958.81 | LHB1B1 | Light harvesting chlorophyll protein complex II subunit B1 |

| AT3G08940 | 3027.19 | 1449.15 | 3533.29 | 3026.97 | LHCB4.2 | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein CP29.2 |

| AT1G51400 | 1851.61 | 886.74 | 2086.64 | 2069.37 | Photosystem II 5kD protein | |

| AT2G34430 | 187.98 | 155.10 | 290.55 | 340.92 | LHB1B1 | LHC II subunit B1 |

| AT2G23670 | 187.98 | 155.10 | 290.55 | 340.92 | YCF37 | |

| AT1G03630 | 183.08 | 99.92 | 212.62 | 230.60 | PORC | Protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase C |

| Carbohydrate Metabolism and Cellulose Synthesis | ||||||

| AT1G64390 | 59.50 | 35.02 | 96.35 | 99.01 | Glycosyl hydrolase 9C2 | |

| AT2G01290 | 13.39 | 18.80 | 28.15 | 33.23 | Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase 2 | |

| AT1G70230 | 8.11 | 9.73 | 16.53 | 15.36 | Trichome Birefringence-Like 27 | |

| AT1G09350 | 24.01 | 8.36 | 45.35 | 36.17 | Galactinol synthase 3 | |

| Growth and Hormone Signaling | ||||||

| AT1G21310 | 32.88 | 197.79 | 33.87 | 31.90 | EXT3 | Extensin 3 |

| AT1G76930 | 73.22 | 149.21 | 53.68 | 60.34 | EXT4 | Extensin 4 |

| AT1G20190 | 59.51 | 26.15 | 93.85 | 83.53 | EXPA11 | Expansin 11 |

| AT2G20750 | 7.22 | 3.03 | 14.97 | 15.91 | EXPB1 | Expansin B1 |

| AT2G40610 | 50.54 | 18.78 | 99.07 | 79.61 | EXPA8 | Expansin A8 |

| AT5G57560 | 77.60 | 111.40 | 28.68 | 21.14 | TCH4 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase |

| AT2G14620 | 1.10 | 9.39 | 0.72 | 0.99 | XTH10 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 10 |

| AT3G44990 | 29.15 | 26.58 | 73.92 | 99.89 | XTH31 | Xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase-related 8 |

| AT2G21210 | 25.55 | 15.99 | 53.74 | 65.71 | SAUR6 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family |

| AT4G38860 | 27.84 | 11.74 | 56.72 | 52.80 | SAUR16 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family |

| AT1G75580 | 4.29 | 4.93 | 8.13 | 10.95 | SAUR51 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family |

| AT4G38840 | 97.43 | 43.53 | 134.62 | 150.76 | SAUR14 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family |

| AT4G38850 | 9.36 | 3.92 | 15.98 | 15.53 | SAUR15 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family |

| AT3G53250 | 1.95 | 0.68 | 4.90 | 3.47 | SAUR57 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein family |

| AT1G23080 | 65.86 | 32.20 | 94.83 | 82.05 | PIN7 | Auxin efflux carrier family protein |

| AT2G46870 | 4.70 | 3.63 | 9.38 | 8.47 | AP2/B3-like TF, auxin response. | |

| AT5G13320 | 3.71 | 16.08 | 2.97 | 3.60 | PBS3 | Auxin-responsive GH3 family protein |

| AT4G12550 | 4.01 | 1.69 | 5.66 | 6.45 | AIR1 | Auxin-Induced in Root cultures 1 |

| AT1G52830 | 4.59 | 1.53 | 6.79 | 4.16 | IAA6 | Indole-3-acetic acid 6 |

| AT1G74670 | 150.45 | 33.60 | 188.25 | 141.53 | GASA6 | Gibberellin-regulated family protein |

| AT1G02400 | 7.18 | 18.48 | 5.67 | 5.18 | GA2OX6 | Gibberellin 2-oxidase 6 (inactivates gibberellin) |

| AT1G15550 | 8.09 | 2.49 | 5.96 | 6.32 | GA3OX1 | Gibberellin 3-oxidase 1 |

| Autophagy | ||||||

| AT2G38470 | 48.75 | 142.40 | 26.84 | 36.51 | WRKY33 | WRKY DNA-binding protein 33 |

| AT2G45170 | 82.62 | 98.94 | 38.58 | 32.66 | ATG8E | AUTOPHAGY 8E |

| AT3G06420 | 18.68 | 35.54 | 14.28 | 14.12 | ATG8H | AUTOPHAGY 8H |

| Lipid Metabolism | ||||||

| AT1G19020 | 36.57 | 247.44 | 26.24 | 33.40 | CDP-diacylglycerol-glycerol-3-phosphate 3-phosphatidyltransferase | |

| AT4G34200 | 75.62 | 216.87 | 76.14 | 74.59 | EDA9 | D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase |

| AT4G39670 | 3.43 | 50.87 | 2.08 | 2.82 | Glycolipid transfer protein (GLTP) family protein | |

| AT1G67800 | 10.05 | 23.91 | 10.77 | 12.32 | Copine (Calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding protein) family | |

| AT3G55470 | 18.33 | 57.91 | 20.04 | 21.00 | Ca-dependent lipid-binding (CaLB domain) | |

| AT5G14180 | 1.77 | 5.23 | 0.84 | 0.62 | MPL1 | Myzus persicae-induced lipase 1 |

| AT2G26560 | 45.59 | 364.62 | 38.48 | 42.54 | PLA2A | Phospholipase A 2A |

| AT1G13930 | 2740.50 | 1898.62 | 4318.3 | 3952.83 | Oleosin-B3 like protein | |

| AT1G51080 | 18.67 | 11.26 | 25.10 | 27.68 | Golgin family A proteins | |

| AT1G25054 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 6.08 | 3.07 | LPXC3, LPXC4 | UDP-3-O-acyl N-acetylglycosamine deacetylase |

| Transcription Factors and Stress-Related Genes | ||||||

| AT1G59930 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 8.94 | 10.58 | MADS-box transcription factor | |

| AT1G70890 | 136.76 | 85.38 | 171.01 | 170.27 | MLP43 | MLP-like protein 43 |

| AT1G75690 | 184.17 | 98.65 | 215.40 | 223.10 | DnaJ/Hsp40 | |

| AT1G78070 | 43.04 | 33.13 | 77.16 | 73.50 | Transducin/WD40 | |

| AT2G28720 | 95.98 | 74.93 | 131.89 | 151.73 | HTB3 | Histone super family protein |

| AT2G41090 | 300.65 | 461.43 | 464.31 | 652.82 | CML10 | Calcium-binding EF-hand family protein |

| AT2G44940 | 7.88 | 6.32 | 20.17 | 28.83 | Integrase-type DNA-binding | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omidbakhshfard, M.A.; Sujeeth, N.; Gupta, S.; Omranian, N.; Guinan, K.J.; Brotman, Y.; Nikoloski, Z.; Fernie, A.R.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. A Biostimulant Obtained from the Seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum Protects Arabidopsis thaliana from Severe Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 474. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21020474

Omidbakhshfard MA, Sujeeth N, Gupta S, Omranian N, Guinan KJ, Brotman Y, Nikoloski Z, Fernie AR, Mueller-Roeber B, Gechev TS. A Biostimulant Obtained from the Seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum Protects Arabidopsis thaliana from Severe Oxidative Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(2):474. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21020474

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmidbakhshfard, Mohammad Amin, Neerakkal Sujeeth, Saurabh Gupta, Nooshin Omranian, Kieran J. Guinan, Yariv Brotman, Zoran Nikoloski, Alisdair R. Fernie, Bernd Mueller-Roeber, and Tsanko S. Gechev. 2020. "A Biostimulant Obtained from the Seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum Protects Arabidopsis thaliana from Severe Oxidative Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 2: 474. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21020474