Understanding Plant Social Networking System: Avoiding Deleterious Microbiota but Calling Beneficials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

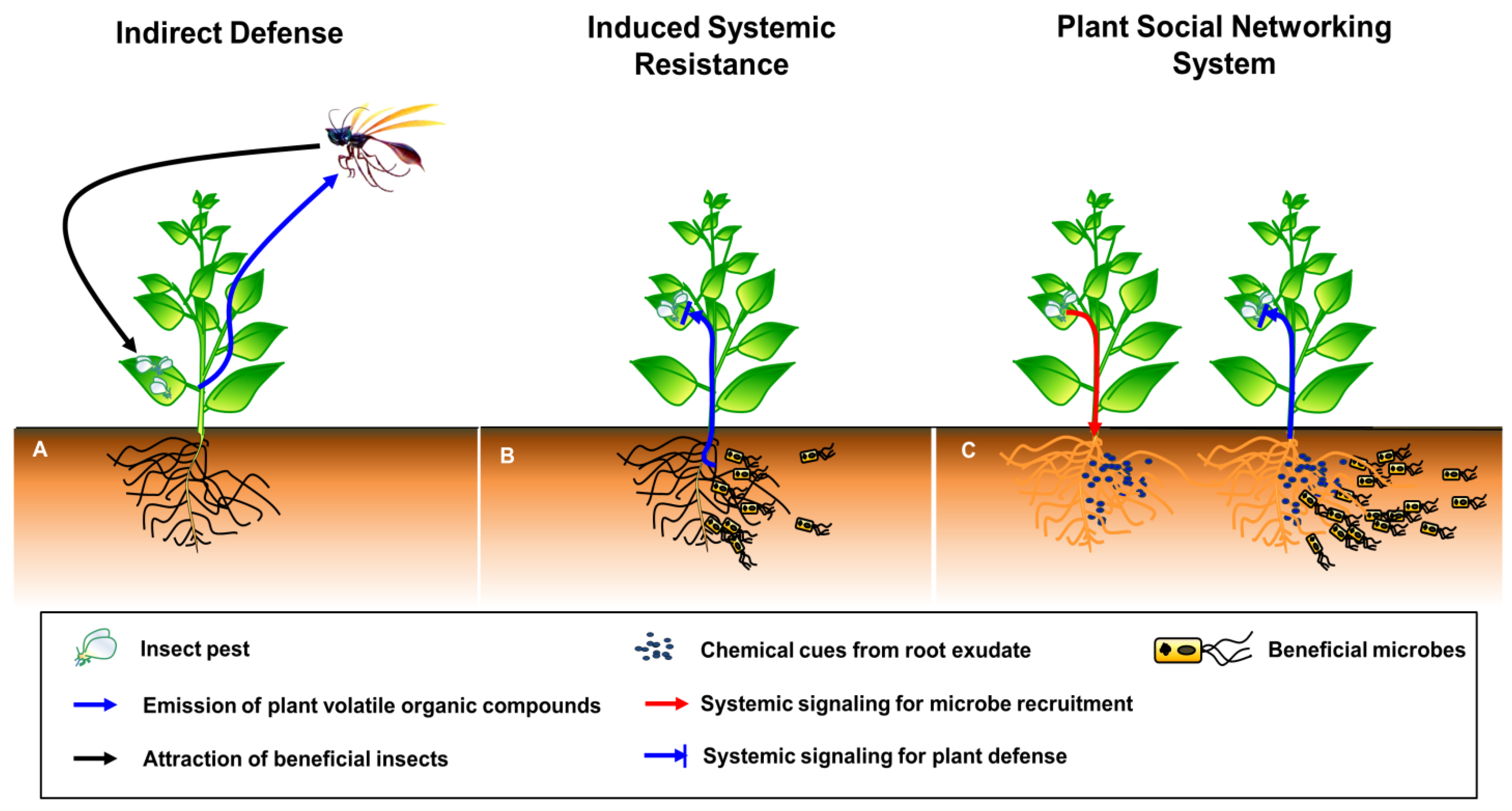

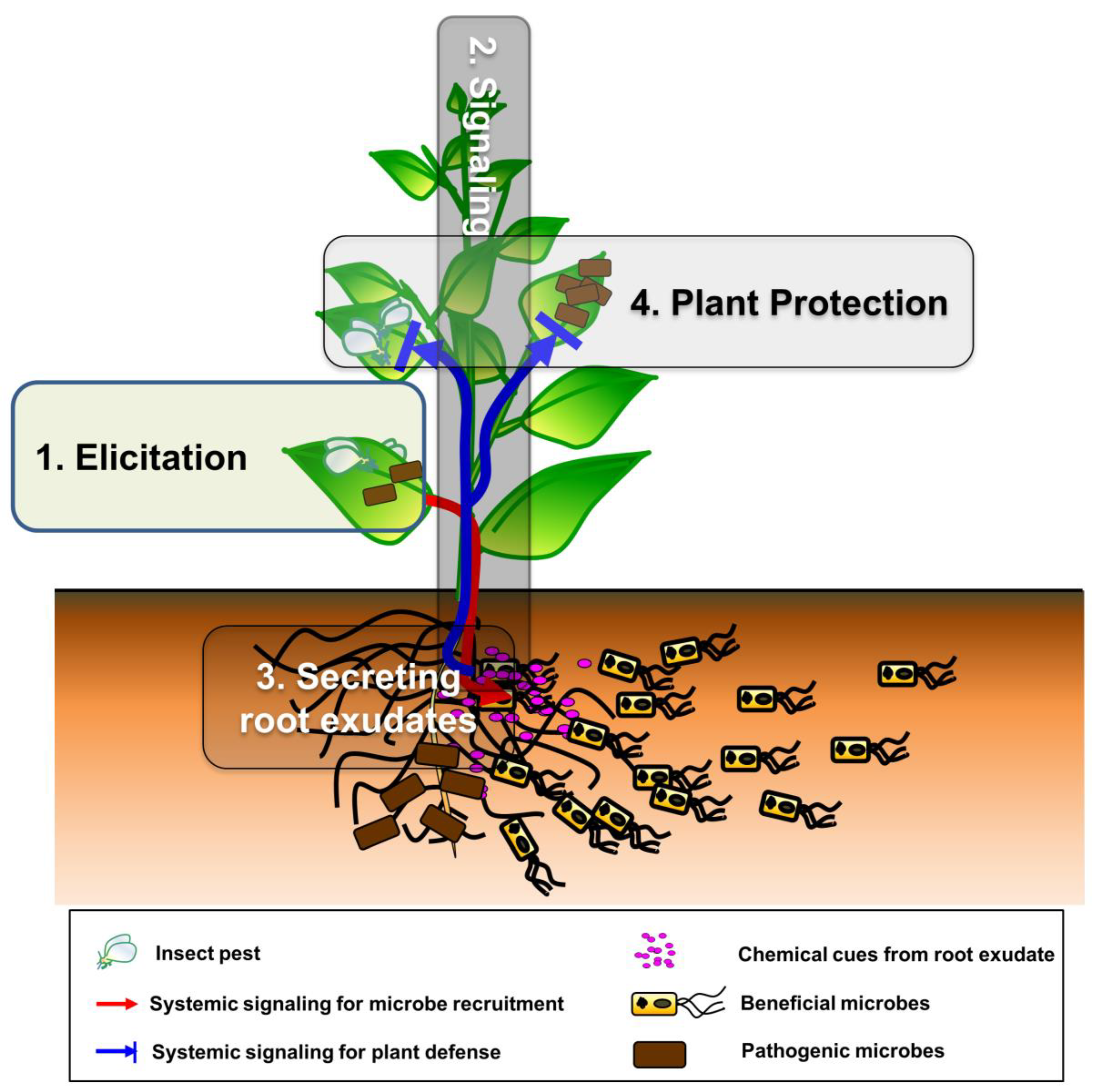

2. The Plant SNS Hypothesis

3. Building Blocks and Molecular Mechanisms of the Plant SNS

3.1. Elicitation: Plant Incuction in a Local Area by Insect and Pathogen Attacks

3.2. Signaling: Activation and Transduction of Systemic Signaling Molecules

3.2.1. SA and Methyl Salicylate

3.2.2. JA and Its Derivatives

3.2.3. Gaseous Signals VOCs

3.2.4. Lipid-Derived Signals

3.3. Secreting Root Exudates: Plant Secretion of Bioactive Root Exudates and Chemicals into the Rhizosphere

3.3.1. Secretion of Strigolactones (SLs), Flavonoids and Coumarins under Nutrient Limitation Conditions

3.3.2. Secretion of Malic Acid and Phenolic/Organic Acid Compounds upon Pathogen Infection

3.3.3. Secretion of Benzoxazinoids and SA upon Insect Infestation

3.4. Plant Protection

3.4.1. Recruitment of Beneficial Microbes by Root Exudates

3.4.2. Antibiosis and Antimicrobial Compounds

3.4.3. Induced Systemic Resistance

3.5. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Plant SNS

4. Technological Limitations, Fundamental Issues, and Potential Troubleshooting Approaches

5. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hauser, T.P.; Christensen, S.; Heimes, C.; Kiaer, L.P. Combined effects of arthropod herbivores and phytopathogens on plant performance. Funct. Ecol. 2013, 27, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, R.; Harvey, J.A.; Bezemer, T.M.; Stuefer, J.F. Plants as green phones: Novel insights into plant-mediated communication between below- and above-ground insects. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieterse, C.M.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.; Bakker, P.A. Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Geem, M.; Gols, R.; van Dam, N.M.; van der Putten, W.H.; Fortuna, T.; Harvey, J.A. The importance of aboveground-belowground interactions on the evolution and maintenance of variation in plant defense traits. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 431. [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Vismans, G.; Yu, K.; Song, Y.; de Jonge, R.; Burgman, W.P.; Burmølle, M.; Herschend, J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Disease-induced assemblage of a plant-beneficial bacterial consortium. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glick, B.R. Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, M.A.; Durán, P.; Hacquard, S. Microbial interactions within the plant holobiont. Microbiome 2018, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacquard, S.; Garrido-Oter, R.; González, A.; Spaepen, S.; Ackermann, G.; Lebeis, S.; McHardy, A.C.; Dangl, J.L.; Knight, R.; Ley, R.; et al. Microbiota and host nutrition across plant and animal kingdoms. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; de Jonge, R.; Berendsen, R.L. The soil-borne legacy. Cell 2018, 172, 1178–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durán, P.; Thiergart, T.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Agler, M.; Kemen, E.; Schulze-Lefert, P.; Hacquard, S. Microbial interkingdom interactions in roots promote Arabidopsis survival. Cell 2018, 175, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, S.; Ryu, C.M. Foliar aphid feeding recruits rhizosphere bacteria and primes plant immunity against pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria in pepper. Ann. Bot. 2012, 110, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.C.; Lee, S.; Hong, J.; Choi, H.K.; Hong, G.H.; Bae, D.W.; Mysore, K.S.; Park, Y.S.; Ryu, C.M. Aboveground insect infestation attenuates belowground Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. New Phytol. 2015, 207, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Kong, H.G.; Song, G.C.; Ryu, C.M. Disruption of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria abundance in tomato rhizosphere causes the incidence of bacterial wilt disease. ISME J. 2021, 15, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.G.; Song, G.C.; Sim, H.J.; Ryu, C.M. Achieving similar root microbiota composition in neighbouring plants through airborne signalling. ISME J. 2021, 15, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, R.; Ryu, C.M. Social networking in crop plants: Wired and wireless cross-plant communications. Plant Cell Environ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, M.; van Poecke, R.M.P. Signalling in plant-insect interactions: Signal transduction in direct and indirect plant defence. In Plant Signal Transduction; Scheel, D., Wasternack, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 289–316. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenbucher, S.; Olson, D.M.; Ruberson, J.R.; Wäckers, F.L.; Romeis, J. Resistance mechanisms against arthropod herbivores in cotton and their interactions with natural enemies. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2013, 32, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhou, W.; Pottinger, S.; Baldwin, I.T. Herbivore associated elicitor-induced defences are highly specific among closely related Nicotiana species. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aljbory, Z.; Chen, M.S. Indirect plant defense against insect herbivores: A review. Insect Sci. 2018, 25, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Pieterse, C.M.; Bakker, P.A. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, A.; Zheng, S.J.; van Loon, J.J.; Pieterse, C.M.; Dicke, M. Helping plants to deal with insects: The role of beneficial soil-borne microbes. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partida-Martínez, L.P.; Heil, M. The microbe-free plant: Fact or artifact? Front. Plant Sci. 2011, 2, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zamioudis, C.; Pieterse, C.M. Modulation of host immunity by beneficial microbes. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2012, 25, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glazebrook, J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.; Van der Does, D.; Zamioudis, C.; Leon-Reyes, A.; Van Wees, S.C. Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012, 28, 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van der Ent, S.; Van Wees, S.C.; Pieterse, C.M. Jasmonate signaling in plant interactions with resistance-inducing beneficial microbes. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schenk, S.T.; Schikora, A. AHL-priming functions via oxylipin and salicylic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, C.M.; De Cremer, K.; Cammue, B.P.; De Coninck, B. The toolbox of Trichoderma spp. in the biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 16, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boller, T.; Felix, G. A renaissance of elicitors: Perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrenner, A.D.; Muñoz-Amatriaín, M.; Chaparro, A.F.; Aguilar-Venegas, J.M.; Lo, S.; Okuda, S.; Glauser, G.; Dongiovanni, J.; Shi, D.; Hall, M.; et al. A receptor-like protein mediates plant immune responses to herbivore-associated molecular patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 31510–31518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm, S.T.; Coaker, G.; Day, B.; Staskawicz, B.J. Host-microbe interactions: Shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 2006, 124, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gómez-Gómez, L.; Boller, T. Flagellin perception: A paradigm for innate immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, C.; Kunze, G.; Chinchilla, D.; Caniard, A.; Jones, J.D.; Boller, T.; Felix, G. Perception of the bacterial PAMP EF-Tu by the receptor EFR restricts Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Cell 2006, 125, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alborn, H.T.; Hansen, T.V.; Jones, T.H.; Bennett, D.C.; Tumlinson, J.H.; Schmelz, E.A.; Teal, P.E.A. Disulfooxy fatty acids from the American bird grasshopper Schistocerca americana, elicitors of plant volatiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12976–12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doss, R.P.; Oliver, J.E.; Proebsting, W.M.; Potter, S.W.; Kuy, S.R.; Clement, S.L.; Williamson, R.T.; Carney, J.R.; DeVilbiss, E.D. Bruchins: Insect-derived plant regulators that stimulate neoplasm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6218–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmelz, E.A.; LeClere, S.; Carroll, M.J.; Alborn, H.T.; Teal, P.E.A. Cowpea chloroplastic ATP synthase is the source of multiple plant defense elicitors during insect herbivory. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Truitt, C.L.; Wei, H.X.; Paré, P.W. A plasma membrane protein from Zea mays binds with the herbivore elicitor volicitin. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeworutzki, E.; Roelfsema, M.R.; Anschütz, U.; Krol, E.; Elzenga, J.T.; Felix, G.; Boller, T.; Hedrich, R.; Becker, D. Early signaling through the Arabidopsis pattern recognition receptors FLS2 and EFR involves Ca-associated opening of plasma membrane anion channels. Plant J. 2010, 62, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranf, S.; Eschen-Lippold, L.; Pecher, P.; Lee, J.; Scheel, D. Interplay between calcium signalling and early signalling elements during defence responses to microbe- or damage-associated molecular patterns. Plant J. 2011, 68, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colcombet, J.; Hirt, H. Arabidopsis MAPKs: A complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochem. J. 2008, 413, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.A. The systemin signaling pathway: Differential activation of plant defensive genes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1477, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Okamoto, M.; Seto, H.; Ishizuka, K.; Sano, H.; Ohashi, Y. Tobacco MAP kinase: A possible mediator in wound signal transduction pathways. Science 1995, 270, 1988–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, T.; Friedrich, L.; Vernooij, B.; Negrotto, D.; Nye, G.; Uknes, S.; Ward, E.; Kessmann, H.; Ryals, J. Requirement of salicylic acid for the induction of systemic acquired resistance. Science 1993, 261, 754–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamy, J.; Carr, J.P.; Klessig, D.F.; Raskin, I. Salicylic acid: A likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science 1990, 250, 1002–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Métraux, J.P.; Signer, H.; Ryals, J.; Ward, E.; Wyss-Benz, M.; Gaudin, J.; Raschdorf, K.; Schmid, E.; Blum, W.; Inverardi, B. Increase in salicylic acid at the onset of systemic acquired resistance in cucumber. Science 1990, 250, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delaney, T.P.; Friedrich, L.; Ryals, J.A. Arabidopsis signal transduction mutant defective in chemically and biologically induced disease resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 6602–6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nawrath, C.; Métraux, J.P. Salicylic acid induction-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath, C.; Heck, S.; Parinthawong, N.; Métraux, J.P. EDS5, an essential component of salicylic acid-dependent signaling for disease resistance in Arabidopsis, is a member of the MATE transporter family. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Tsuda, K.; Truman, W.; Sato, M.; Nguyen, L.V.; Katagiri, F.; Glazebrook, J. CBP60g and SARD1 play partially redundant critical roles in salicylic acid signaling. Plant J. 2011, 67, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildermuth, M.C.; Dewdney, J.; Wu, G.; Ausubel, F.M. Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature 2001, 414, 562–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Ding, P.; Wang, D.; Cheng, Y.T.; He, J.; Gao, M.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Control of salicylic acid synthesis and systemic acquired resistance by two members of a plant-specific family of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18220–18225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Attaran, E.; Zeier, T.E.; Griebel, T.; Zeier, J. Methyl salicylate production and jasmonate signaling are not essential for systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 954–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.I.; Raskin, I. Purification, cloning, and expression of a pathogen inducible UDP-glucose:salicylic acid glucosyltransferase from tobacco. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 36637–36642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malamy, J.; Hennig, J.; Klessig, D.F. Temperature-dependent induction of salicylic acid and its conjugates during the resistance response to tobacco mosaic-virus infection. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulaev, V.; Silverman, P.; Raskin, I. Airborne signaling by methyl salicylate in plant pathogen resistance. Nature 1997, 385, 718–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, D.A.; Klessig, D.F. SOS-too many signals for systemic acquired resistance? Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Kaiyomo, E.; Kumar, D.; Mosher, S.L.; Klessig, D.F. Methyl salicylate is a critical mobile signal for plant systemic acquired resistance. Science 2007, 318, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Liu, P.P.; Forouhar, F.; Vlot, A.C.; Tong, L.; Tietjen, K.; Klessig, D.F. Use of a synthetic salicylic acid analog to investigate the roles of methyl salicylate and its esterases in plant disease resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 7307–7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vlot, A.C.; Dempsey, D.A.; Klessig, D.F. Salicylic Acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009, 47, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Butselaar, T.; Van den Ackerveken, G. Salicylic acid steers the growth-immunity tradeoff. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Clinton, M.; Qi, G.; Wang, D.; Liu, F.; Fu, Z.Q. Reprogramming and remodeling: Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of salicylic acid-mediated plant defense. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5256–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimura, G.; Matsui, K.; Takabayashi, J. Chemical and molecular ecology of herbivore-induced plant volatiles: Proximate factors and their ultimate functions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koo, A.J.; Howe, G.A. The wound hormone jasmonate. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorman, Z.; Christensen, S.A.; Yan, Y.; He, Y.; Borrego, E.; Kolomiets, M.V. Green leaf volatiles and jasmonic acid enhance susceptibility to anthracnose diseases caused by Colletotrichum graminicola in maize. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hause, B.; Stenzel, I.; Miersch, O.; Maucher, H.; Kramell, R.; Ziegler, J.; Wasternack, C. Tissue-specific oxylipin signature of tomato flowers–allene oxide cyclase is highly expressed in distinct flower organs and vascular bundles. Plant J. 2000, 24, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacinto, T.; McGurl, B.; Francheschi, V.; Delano-Freier, J.; Ryan, C.A. Tomato prosystemin promoter confers wound-inducible, vascular bundle-specific expression of the β-glucuronidase gene in transgenic tomato plants. Planta 1997, 203, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blée, E. Impact of phyto-oxylipins in plant defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, A.; Graham, I.A. Oxylipin signaling: A distinct role for the jasmonic acid precursor cis-(+)-12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (cis-OPDA). Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feussner, I.; Wasternack, C. The lipoxygenase pathway. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002, 53, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narvaez-Vasquez, J.; Florin-Christensen, J.; Ryan, C.A. Positional specificity of a phospholipase-A activity induced by wounding, systemin, and oligosaccharide elicitors in tomato leaves. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 2249–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farmer, E.E. Plant biology: Jasmonate perception machines. Nature 2007, 448, 659–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Wang, L.; Giri, A.; Baldwin, I.T. Silencing threonine deaminase and JAR4 in Nicotiana attenuata impairs jasmonic acid-isoleucine-mediated defenses against Manduca sexta. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 3303–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Staswick, P.E.; Tiryaki, I. The oxylipin signal jasmonic acid is activated by an enzyme that conjugates it to isoleucine in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2117–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheong, J.J.; Choi, Y.D. Methyl jasmonate as a vital substance in plants. Trends Genet. 2003, 19, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, M.; van Loon, J.J.A. Multitrophic effects of herbivore-induced plant volatiles in an evolutionary context. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2000, 97, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kessler, A.; Baldwin, I.T. Defensive function of herbivore-induced plant volatile emissions in nature. Science 2001, 291, 2141–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiners, T.; Hilker, M. Induction of plant synomones by oviposition of a phytophagous insect. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Holst, T.; Michelsen, A.; Rinnan, R. Amplification of plant volatile defence against insect herbivory in a warming Arctic tundra. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Cseke, L.; Blanc, V.M.; Pichersky, E. Evolution of floral scent in Clarkia: Novel patterns of S-linalool synthase gene expression in the C. breweri flower. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Pichersky, E.; Noel, J.P.; Dudareva, N. Biosynthesis of plant volatiles: Nature’s diversity and ingenuity. Science 2006, 311, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vancanneyt, G.; Sanz, C.; Farmaki, T.; Paneque, M.; Ortego, F.; Castañera, P.; Sánchez-Serrano, J.J. Hydroperoxide lyase depletion in transgenic potato plants leads to an increase in aphid performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 8139–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bate, N.J.; Rothstein, S.J. C-6-volatiles derived from the lipoxygenase pathway induce a subset of defense-related genes. Plant J. 1998, 16, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, E.E. Surface-to-air signals. Nature 2001, 411, 854–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, P.W.; Tumlinson, J.H. De novo biosynthesis of volatiles induced by insect herbivory in cotton plants. Plant Physiol. 1997, 114, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turlings, T.C.J.; Lengwiler, U.B.; Bernasconi, M.L.; Wechsler, D. Timing of induced volatile emissions in maize seedlings. Planta 1998, 207, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaturvedi, R.; Venables, B.; Petros, R.A.; Nalam, V.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Takemoto, L.J.; Shah, J. An abietane diterpenoid is a potent activator of systemic acquired resistance. Plant J. 2012, 71, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, A.M.; Doerner, P.; Dixon, R.A.; Lamb, C.J.; Cameron, R.K. A putative lipid transfer protein involved in systemic resistance signaling in Arabidopsis. Nature 2002, 419, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, B.; Xia, Y.; Mandal, M.K.; Yu, K.; Sekine, K.T.; Gao, Q.M.; Selote, D.; Hu, Y.; Stromberg, A.; Navarre, D.; et al. Glycerol-3-phosphate is a critical mobile inducer of systemic immunity in plants. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.W.; Tschaplinkski, T.J.; Wang, L.; Glazebrook, J.; Greenberg, J.T. Priming in systemic plant immunity. Science 2009, 324, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.P.; von Dahl, C.C.; Park, S.W.; Klessig, D.F. Interconnection between methyl salicylate and lipid-based long-distance signaling during the development of systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis and tobacco. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nandi, A.; Welti, R.; Shah, J. The Arabidopsis thaliana dihydroxyacetone phosphate reductase gene suppressor of fatty acid desaturase deficiency1 is required for glycerolipid metabolism and for the activation of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lorenc-Kukula, K.; Chaturvedi, R.; Roth, M.; Welti, R.; Shah, J. Biochemical and molecular-genetic characterization of the Arabidopsis thaliana SFD1-encoded dihydroxyacetone phosphate reductase. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chaturvedi, R.; Krothapalli, K.; Makandar, R.; Nandi, A.; Sparks, A.A.; Roth, M.R.; Welti, R.; Shah, J. Plastid ω-3 desaturase-dependent accumulation of a systemic acquired resistance inducing activity in petiole exudates of Arabidopsis thaliana is independent of jasmonic acid. Plant J. 2008, 54, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoeller, M.; Stingl, N.; Krischke, M.; Fekete, A.; Waller, F.; Berger, S.; Mueller, M.J. Lipid profiling of the Arabidopsis hypersensitive response reveals specific lipid peroxidation and fragmentation processes: Biogenesis of pimelic and azelaic acid. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, K.; Soares, J.M.; Mandal, M.K.; Wang, C.; Chanda, B.; Gifford, A.N.; Fowler, J.S.; Navarre, D.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. A feedback regulatory loop between G3P and lipid transfer proteins DIR1 and AZI1 mediates azelaic-acid-induced systemic immunity. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1266–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; El-Shetehy, M.; Shine, M.B.; Yu, K.; Navarre, D.; Wendehenne, D.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Free radicals mediate systemic acquired resistance. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, H.P.; Weir, T.L.; Perry, L.G.; Gilroy, S.; Vivanco, J.M. The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dennis, P.G.; Miller, A.J.; Hirsch, P.R. Are root exudates more important than other sources of rhizodeposits in structuring rhizosphere bacterial communities? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 72, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascale, A.; Proietti, S.; Pantelides, I.S.; Stringlis, I.A. Modulation of the root microbiome by plant molecules: The basis for targeted disease suppression and plant growth promotion. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, S.A.; Griffiths, J.; Ton, J. Crying out for help with root exudates: Adaptive mechanisms by which stressed plants assemble health-promoting soil microbiomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 49, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, J.; Martinoia, E.; Northen, T. Feed your friends: Do plant exudates shape the root microbiome? Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verbon, E.H.; Trapet, P.L.; Stringlis, I.A.; Kruijs, S.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Iron and Immunity. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017, 55, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Babili, S.; Bouwmeester, H.J. Strigolactones, a novel carotenoid-derived plant hormone. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, K.; Yoneyama, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Sekimoto, H. Phosphorus deficiency in red clover promotes exudation of orobanchol, the signal for mycorrhizal symbionts and germination stimulant for root parasites. Planta 2007, 225, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Roldan, V.; Girard, D.; Bécard, G.; Puech, V. Strigolactones: Promising plant signals. Plant Signal. Behav. 2007, 2, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Lateif, K.; Bogusz, D.; Hocher, V. The role of flavonoids in the establishment of plant roots endosymbioses with arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi, rhizobia and Frankia bacteria. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, H.H.; Schmidt, W. Mobilization of iron by plant-borne coumarins. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourcroy, P.; Sisó-Terraza, P.; Sudre, D.; Savirón, M.; Reyt, G.; Gaymard, F.; Abadía, A.; Abadia, J.; Alvarez-Fernández, A.; Briat, J.F. Involvement of the ABCG37 transporter in secretion of scopoletin and derivatives by Arabidopsis roots in response to iron deficiency. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajniak, J.; Giehl, R.F.H.; Chang, E.; Murgia, I.; von Wirén, N.; Sattely, E.S. Biosynthesis of redox-active metabolites in response to iron deficiency in plants. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Günther, C.; Weber, M.; Spörlein, C.; Loscher, S.; Böttcher, C.; Schobert, R.; Clemens, S. Metabolome analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana roots identifies a key metabolic pathway for iron acquisition. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siwinska, J.; Siatkowska, K.; Olry, A.; Grosjean, J.; Hehn, A.; Bourgaud, F.; Meharg, A.A.; Carey, M.; Lojkowska, E.; Ihnatowicz, A. Scopoletin 8-hydroxylase: A novel enzyme involved in coumarin biosynthesis and iron-deficiency responses in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 1735–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaeger, C.H., III; Lindow, S.E.; Miller, W.; Clark, E.; Firestone, M.K. Mapping of sugar and amino acid availability in soil around roots with bacterial sensors of sucrose and tryptophan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 2685–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, J.; Zhao, J.; Wen, T.; Zhao, M.; Li, R.; Goossens, P.; Huang, Q.; Bai, Y.; Vivanco, J.M.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; et al. Root exudates drive the soil-borne legacy of aboveground pathogen infection. Microbiome 2018, 6, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bezemer, T.M.; van Dam, N.M. Linking aboveground and belowground interactions via induced plant defenses. Trends. Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jousset, A.; Rochat, L.; Lanoue, A.; Bonkowski, M.; Keel, C.; Scheu, S. Plants respond to pathogen infection by enhancing the antifungal gene expression of root-associated bacteria. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bais, H.P.; Walker, T.S.; Schweizer, H.P.; Vivanco, J.M. Root specific elicitation and antimicrobial activity of rosmarinic acid in hairy root cultures of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 40, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanoue, A.; Burlat, V.; Henkes, G.J.; Koch, I.; Schurr, U.; Röse, U.S. De novo biosynthesis of defense root exudates in response to Fusarium attack in barley. New Phytol. 2010, 185, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, I.; Halitschke, R.; Kessler, A.; Sardanelli, S.; Denno, R.F. Effects of plant vascular architecture on aboveground–belowground-induced responses to foliar and root herbivores on Nicotiana tabacum. J. Chem. Ecol. 2008, 34, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balendres, M.A.; Nichols, D.S.; Tegg, R.S.; Wilson, C.R. Metabolomes of potato root exudates: Compounds that stimulate resting spore germination of the soil-borne pathogen Spongospora subterranea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 7466–7674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yu, J.; Gan, L.; Sun, J. Effects of tobacco pathogens and their antagonistic bacteria on tobacco root exudates. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pétriacq, P.; Williams, A.; Cotton, A.; McFarlane, A.E.; Rolfe, S.A.; Ton, J. Metabolite profiling of non-sterile rhizosphere soil. Plant J. 2017, 92, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.A.; Veyrat, N.; Glauser, G.; Marti, G.; Doyen, G.R.; Villard, N.; Gaillard, M.D.; Köllner, T.G.; Giron, D.; Body, M.; et al. A specialist root herbivore exploits defensive metabolites to locate nutritious tissues. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Robert, C.A.M.; Cadot, S.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M.; Li, B.; Manzo, D.; Chervet, N.; Steinger, T.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; et al. Root exudate metabolites drive plant-soil feedbacks on growth and defense by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasmann, S.; Köllner, T.G.; Degenhardt, J.; Hiltpold, I.; Toepfer, S.; Kuhlmann, U.; Gershenzon, J.; Turlings, T.C. Recruitment of entomopathogenic nematodes by insect-damaged maize roots. Nature 2005, 434, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.G.; Alborn, H.T.; Stelinski, L.L. Subterranean herbivore-induced volatiles released by citrus roots upon feeding by Diaprepes abbreviatus recruit entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.W.; Yi, H.S.; Kim, H.; Lee, B.; Lee, S.; Ghim, S.Y.; Ryu, C.M. Whitefly infestation of pepper plants elicits defence responses against bacterial pathogens in leaves and roots and changes the below-ground microflora. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoysted, G.A.; Bell, C.A.; Lilley, C.J.; Urwin, P.E. Aphid colonization affects potato root exudate composition and the hatching of a soil borne pathogen. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravesi, K.; Aikio, S.; Wäli, P.R.; Ruotsalainen, A.L.; Kaukonen, M.; Huusko, K.; Suokas, M.; Brown, S.P.; Jumpponen, A.; Tuomi, J.; et al. Moth outbreaks alter root-associated fungal communities in subarctic mountain birch forests. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankau, R.A.; Wheeler, E.; Bennett, A.E.; Strauss, S.Y. Plant–soil feedbacks contribute to an intransitive competitive network that promotes both genetic and species diversity. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.L.; Ahmad, S.; Gordon-Weeks, R.; Ton, J. Benzoxazinoids in root exudates of maize attract Pseudomonas putida to the rhizosphere. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Antoniou, A.; Tsolakidou, M.D.; Stringlis, I.A.; Pantelides, I.S. Rhizosphere microbiome recruited from a suppressive compost improves plant fitness and increases protection against vascular wilt pathogens of tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lombardi, N.; Vitale, S.; Turrà, D.; Reverberi, M.; Fanelli, C.; Vinale, F.; Marra, R.; Ruocco, M.; Pascale, A.; d’Errico, G.; et al. Root exudates of stressed plants stimulate and attract Trichoderma soil fungi. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2018, 31, 982–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lundberg, D.S.; Teixeira, P.J.P.L. Root-exuded coumarin shapes the root microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5629–5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Mazzola, M. ECOLOGY. Soil immune responses. Science 2016, 352, 1392–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrappa, T.; Czymmek, K.J.; Paré, P.W.; Bais, H.P. Root-secreted malic acid recruits beneficial soil bacteria. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapelle, E.; Mendes, R.; Bakker, P.A.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Fungal invasion of the rhizosphere microbiome. ISME J. 2016, 10, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ourry, M.; Lebreton, L.; Chaminade, V.; Guillerm-Erckelboudt, A.Y.; Hervé, M.; Linglin, J.; Marnet, N.; Ourry, A.; Paty, C.; Poinsot, D.; et al. Influence of belowground herbivory on the dynamics of root and rhizosphere microbial communities. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grayston, J.S.; Dawson, L.A.; Treonis, A.M.; Murray, P.J.; Ross, J.; Reid, E.J.; MacDougall, R. Impact of root herbivory by insect larvae on soil microbial communities. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2001, 37, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin-A-Woeng, T.F.; Bloemberg, G.V.; Mulders, I.H.; Dekkers, L.C.; Lugtenberg, B.J. Root colonization by phenazine-1-carboxamide-producing bacterium Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 is essential for biocontrol of tomato foot and root rot. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2000, 13, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haas, D.; Keel, C. Regulation of antibiotic production in root-colonizing Pseudomonas spp. and relevance for biological control of plant disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2003, 41, 117–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrodi, D.V.; Blankenfeldt, W.; Thomashow, L.S. Phenazine compounds in fluorescent pseudomonas spp. biosynthesis and regulation. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 417–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomashow, L.S.; Weller, D.M. Current concepts in the use of introduced bacteria for biological disease control: Mechanisms and antifungal metabolites. In Plant-Microbe Interactions; Stacey, G., Keen, N., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1996; Volume 1, pp. 187–235. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Thompson, B.; Chaney, N.; Wing, J.S.; Gould, S.J.; Loper, J.E. Characterization of the pyoluteorin biosynthetic gene cluster of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 2166–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirner, S.; Hammer, P.E.; Hill, D.S.; Altmann, A.; Fischer, I.; Weislo, L.J.; Lanahan, M.; van Pée, K.H.; Ligon, J.M. Functions encoded by pyrrolnitrin biosynthetic genes from Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 1939–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomashow, L.S.; Weller, D.M. Role of a phenazine antibiotic from Pseudomonas fluorescens in biological control of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici. J. Bacteriol. 1988, 170, 3499–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voisard, C.; Keel, C.; Haas, D.; Dèfago, G. Cyanide production by Pseudomonas fluorescens helps suppress black root rot of tobacco under gnotobiotic conditions. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.; de Vicente, A.; Olmos, J.L.; Dávila, J.C.; Pérez-García, A. Effect of lipopeptides of antagonistic strains of Bacillus subtilis on the morphology and ultrastructure of the cucurbit fungal pathogen Podosphaera fusca. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 103, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazorla, F.M.; Romero, D.; Pérez-García, A.; Lugtenberg, B.J.; de Vicente, A.; Bloemberg, G. Isolation and characterization of antagonistic Bacillus subtilis strains from the avocado rhizoplane displaying biocontrol activity. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 103, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, H.P.; Fall, R.; Vivanco, J.M. Biocontrol of Bacillus subtilis against infection of Arabidopsis roots by Pseudomonas syringae is facilitated by biofilm formation and surfactin production. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baetz, U.; Martinoia, E. Root exudates: The hidden part of plant defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- VanEtten, H.D.; Mansfield, J.W.; Bailey, J.A.; Farmer, E.E. Two classes of plant antibiotics: Phytoalexins versus ‘phytoanticipins’. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 1191–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanoue, A.; Burlat, V.; Schurr, U.; Röse, U.S. Induced root-secreted phenolic compounds as a belowground plant defense. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 1037–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringlis, I.A.; Yu, K.; Feussner, K.; de Jonge, R.; Van Bentum, S.; Van Verk, M.C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Feussner, I.; Pieterse, C.M.J. MYB72-dependent coumarin exudation shapes root microbiome assembly to promote plant health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5213–E5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duchesne, L.C.; Peterson, R.L.; Ellis, B.E. Interaction between the ectomycorrhizal fungus Paxillus involutus and Pinus resinosa induces resistance to Fusarium oxysporum. Can. J. Bot. 1988, 66, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, F.J.; García, M.J.; Lucena, C.; Martínez-Medina, A.; Aparicio, M.A.; Ramos, J.; Alcántara, E.; Angulo, M.; Pérez-Vicente, R. Induced systemic resistance (ISR) and Fe deficiency responses in dicot plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Trotel-Aziz, P.; Villaume, S.; Rabenoelina, F.; Schwarzenberg, A.; Nguema-Ona, E.; Clément, C.; Baillieul, F.; Aziz, A. Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens trigger common and distinct systemic immune responses in Arabidopsis thaliana depending on the pathogen lifestyle. Vaccines 2020, 8, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.D.; Borrego, E.J.; Kenerley, C.M.; Kolomiets, M.V. Oxylipins other than jasmonic acid are xylem-resident signals regulating systemic resistance induced by Trichoderma virens in maize. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Peer, R.; Niemann, G.J.; Schippers, B. Induced resistance and phytoalexin accumulation in biological control of Fusarium wilt of carnation by Pseudomonas spp. strain WCS417r. Phytopathology 1991, 81, 1508–1512. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Kloepper, J.W.; Tuzun, S. Induction of systemic resistance of cucumber to Colletotrichum orbiculare by select strains of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Phytopathology 1991, 81, 1508–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Kloepper, J.W.; Tuzun, S. Induction of systemic resistance to cucumber disease and increased plant growth by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria under field conditions. Phytopathology 1996, 86, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kloepper, J.W.; Tuzun, S. Induction of systemic resistance in cucumber against Fusarium wilt by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kloepper, J.W.; Tuzun, S. Induction of systemic resistance in cucumber against bacterial angular leaf spot by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raupach, G.S.; Liu, L.; Murphy, J.F.; Tuzun, S.; Kloepper, J.W. Induced systemic resistance in cucumber and tomato against cucumber mosaic cucumovirus using plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). Plant Dis. 1996, 80, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloepper, J.W. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria as biological control agents. In Soil Microbial Ecology—Applications in Agricultural and Environmental Management; Metting, F.B., Jr., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.S.; Kloepper, J.W. Activation of PR-1a promoter by rhizobacteria that induce systemic resistance in tobacco against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci. Biol. Control 2000, 18, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Reddy, M.; Kloepper, J. Development of assays for assessing induced systemic resistance by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria against Blue Mold of Tobacco. Biol. Control 2002, 23, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gehring, C.; Bennett, A. Mycorrhizal fungal-plant-insect interactions: The importance of community approach. Environ. Entomol. 2009, 38, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koricheva, J.; Gange, A.C.; Jones, T. Effects of mycorrhizal fungi on insect herbivores: A meta-analysis. Ecology 2009, 90, 2088–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Soto, J.H.; Estrada-Hernández, M.G.; Ibarra-Laclette, E.; Délano-Frier, J.P. Inoculation of tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum) with growth-promoting Bacillus subtilis retards whitefly Bemisia tabaci development. Planta 2010, 231, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, A.; Traoré, M.; Schnitzler, W.; Woitke, M. Induced resistance of tomato to whiteflies and pythium with the PGPR Bacillus subtilis in a soilless crop grown under greenhouse conditions. Acta. Hortic. 2007, 747, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehnder, G.; Kloepper, J.; Yao, C.; Wei, G. Induction of systemic resistance in cucumber against cucumber beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. J. Econ. Entomol. 1997, 90, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, A.; Zheng, S.J.; Van Loon, J.J.A.; Dicke, M. Rhizobacteria modify plant–aphid interactions: A case of induced systemic susceptibility. Plant Biol. 2012, 14, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, I.P.; Lee, S.W.; Suh, S.C. Rhizobacteria-induced priming in Arabidopsis is dependent on ethylene, jasmonic acid, and NPR1. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Hoffland, E.; Van Pelt, J.A.; Van Loon, L.C. Systemic resistance in Arabidopsis induced by biocontrol bacteria is independent of salicylic acid accumulation and pathogenesis-related gene expression. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oosten, V.R.; Bodenhausen, N.; Reymond, P.; Van Pelt, J.A.; Van Loon, L.C.; Dicke, M.; Pieterse, C.M. Differential effectiveness of microbially induced resistance against herbivorous insects in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieterse, C.M.; van Wees, S.C.; van Pelt, J.A.; Knoester, M.; Laan, R.; Gerrits, H.; Weisbeek, P.J.; van Loon, L.C. A novel signaling pathway controlling induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieterse, C.M.; Leon-Reyes, A.; Van der Ent, S.; Van Wees, S.C. Networking by small-molecule hormones in plant immunity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Audenaert, K.; Pattery, T.; Cornelis, P.; Höfte, M. Induction of systemic resistance to Botrytis cinerea in tomato by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 7NSK2: Role of salicylic acid, pyochelin, and pyocyanin. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2002, 15, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Meyer, G.; Capieau, K.; Audenaert, K.; Buchala, A.; Métraux, J.P.; Höfte, M. Nanogram amounts of salicylic acid produced by the rhizobacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa 7NSK2 activate the systemic acquired resistance pathway in bean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1999, 12, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, Y.S.; Ryu, C.M. Understanding cross-communication between aboveground and belowground tissues via transcriptome analysis of a sucking insect whitefly-infested pepper plants. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 443, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Bae, D.W.; Ryu, C.M. Aboveground whitefly infestation modulates transcriptional levels of anthocyanin biosynthesis and jasmonic acid signaling-related genes and augments the cope with drought stress of maize. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, A.C.; Jiang, T.; Liu, Y.X.; Bai, Y.C.; Reed, J.; Qu, B.; Goossens, A.; Nützmann, H.W.; Bai, Y.; Osbourn, A. A specialized metabolic network selectively modulates Arabidopsis root microbiota. Science 2019, 364, eaau6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Weller, D.M. Natural plant protection by 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas spp. in take-all decline soils. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1998, 11, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rolli, E.; Marasco, R.; Vigani, G.; Ettoumi, B.; Mapelli, F.; Deangelis, M.L.; Gandolfi, C.; Casati, E.; Previtali, F.; Gerbino, R.; et al. Improved plant resistance to drought is promoted by the root-associated microbiome as a water stress-dependent trait. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsolakidou, M.D.; Stringlis, I.A.; Fanega-Sleziak, N.; Papageorgiou, S.; Tsalakou, A.; Pantelides, I.S. Rhizosphere-enriched microbes as a pool to design synthetic communities for reproducible beneficial outputs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannier, N.; Agler, M.; Hacquard, S. Microbiota-mediated disease resistance in plants. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chakraborty, S.; Newton, A.C. Climate change, plant diseases and food security: An overview. Plant. Pathol. 2011, 60, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doornbos, R.F.; van Loon, L.C.; Bakker, P.A.H. Impact of root exudates and plant defense signaling on bacterial communities in the rhizosphere. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttimer, C.; McAuliffe, O.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C.; O’Mahony, J.; Coffey, A. Bacteriophages and bacterial plant diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Steps of Plant SNS | Triggers/Determinants | Effect/Mechanisms on Plant | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAMPs/MAMPs/HAMPs: flg22, elf18/elf26, peptidoglycans, chitin, volicitin, inceptins, caeliferin, and bruchin | Plant pattern receptors perceive PAMPs/MAMPs/HAMPs | [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] |

| Ca2+, ROS, MAP Kinase cascades, and phytohormones | Regulation of plant defense responses | [38,39,40,41,42] | |

| SA and Me-SA | Activating systemic resistance against biotrophic pathogens and sucking insects | [43,44,45,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] |

| JA, MeJA, and JA-Ile | Defensive signal against necrotrophic pathogens and chewing insects | [63,71,72,73,74] | |

| Volatile organic compounds (VOCs): C6-alcohol, C6-aldehydes, cis-3-hexen-1-ol trans-2-hexenal, monoterpenes (limonene, linalool, ocimene), and sesquiterpenes (bergamotene, carphyllene and farnesene) | Released by plants in response to a variety of insects | [75,76,77,78,81,82,83,84,85] | |

| Lipid-derived signals: DIR1, G3P, and AzA | Signaling molecules to activate systemic defense responses to pathogens | [86,87,89,91,92,93,94,95] | |

| Stringolactones, flavonoids, and coumains | Secretion under phosphate- and nitrogen-deficient conditions. Effect on the interaction between plant and AM fungi | [104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112] |

| Malic acid, phenolic compounds, and organic acids | Secretion after infection with bacterial and fungal pathogens and nematodes | [5,114,116,117,118,119,120,121] | |

| Benzoxazinoids and SA | Secretion upon insect infestation | [11,12,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129] | |

| Beneficial microbes by root exudates | Recruitment of beneficial microbes from plants infected with pathogens and insects | [5,11,114,124,127,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139] |

| Antibiosis and antimicrobial compounds: hydrogen cyanide, phenazine-1-carboxylic acid, phenazine-1-carboxyamide, 2,4-diacetyl phloroglucinol, pyoluteorin, pyrrolnitrin, phenazine-1-carboxylic acid, t-cinnamic acid, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, syringic acid, vanillic acid, scopoletin, and ethanol-soluble compounds | Direct suppression of pathogens and insects by antibiotics, lipopeptides, phenylpropanoids and ethanol-soluble compounds | [140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155] | |

| Microbes elicit induced systemic resistance | Activation of broad spectrum plant immunity against pathogens and insects | [159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, Y.-S.; Ryu, C.-M. Understanding Plant Social Networking System: Avoiding Deleterious Microbiota but Calling Beneficials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3319. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22073319

Park Y-S, Ryu C-M. Understanding Plant Social Networking System: Avoiding Deleterious Microbiota but Calling Beneficials. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(7):3319. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22073319

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Yong-Soon, and Choong-Min Ryu. 2021. "Understanding Plant Social Networking System: Avoiding Deleterious Microbiota but Calling Beneficials" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 7: 3319. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22073319