Elucidating the Multi-Targeted Role of Nutraceuticals: A Complementary Therapy to Starve Neurodegenerative Diseases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Brief Overview of Neurodegenerative Diseases (NDs)

3. Mechanisms Involved in Neurodegeneration

3.1. Apoptosis

3.2. Oxidative Stress (OS)

- lower endogenous antioxidants reserve levels;

- more oxygen consumption due to higher ATP demand;

- availability of polyunsaturated lipids that are mainly vulnerable to attack of free reactive species in the neuronal cell membrane;

- presence of neurotransmitters and excitatory amino acids, the metabolism of which can generate ROS; and

3.3. Calcium Overload and Excitotoxicity

3.4. Neuroinflammation

3.5. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

4. Nutraceuticals and Its Classification

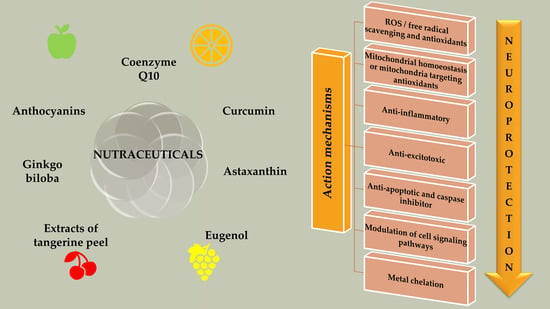

5. Nutraceuticals in NDs: Multi-Targeted Avenue

5.1. Nutraceuticals Targeting OS

5.2. Nutraceuticals Targeting Mitochondrial Dysfunction

5.3. Nutraceuticals Targeting Neuroinflammation

5.4. Nutraceuticals Targeting Apoptosis

5.5. Nutraceuticals Targeting Calcium Overload and Excitotoxicity

6. Conclusions and Futuristic Approaches

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dugger, B.N.; Dickson, D.W. Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.-F.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Wang, C.-K. The role of nutraceuticals as a complementary therapy against various neurodegenerative diseases: A mini-review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2020, 10, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, G.; Sehgal, A.; Bhardwaj, S.; Singh, S.; Buhas, C.; Judea-Pusta, C.; Uivarosan, D.; Munteanu, M.A.; Bungau, S. Multifaceted Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Pathophysiological and Therapeutic Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makkar, R.; Behl, T.; Bungau, S.; Zengin, G.; Mehta, V.; Kumar, A.; Uddin, M.S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Arora, S.; et al. Nutraceuticals in Neurological Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Dawson, T.M.; Dawson, V.L. Cell Death Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration. In Advances in Neurobiology; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sairazi, N.S.; Sirajudeen, K.N.S. Natural Products and Their Bioactive Compounds: Neuroprotective Potentials against Neurodegenerative Diseases. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Mohanakumar, K.P.; Beart, P.M. Neuro-nutraceuticals: The path to brain health via nourishment is not so distant. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, C.; De Ronchi, D.; Fratiglioni, L. The epidemiology of the dementias: An update. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, V.; Tinarelli, C.; Mecocci, P. Nutraceuticals and Cognitive Dysfunction. In Neuroprotective Effects of Phytochemicals in Neurological Disorders; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, A.; Pirozzi, C.; Avagliano, C.; Annunziata, C.; Mollica, M.P.; Calignano, A.; Meli, R.; Mattace Raso, G. Nutraceuticals: An integrative approach to starve Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Tiwari, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, K. Nutraceuticals Inspiring the Current Therapy for Lifestyle Diseases. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 2019, 6908716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistollato, F.; Sachana, M. Prevention of neurodegenerative disorders by nutraceuticals. In Nutraceuticals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandareesh, M.D.; Kandikattu, H.K.; Razack, S.; Amruta, N.; Choudhari, R.; Vikram, A.; Doddapattar, P. Nutrition and Nutraceuticals in Neuroinflammatory and Brain Metabolic Stress: Implications for Neurodegenerative Disorders. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2018, 17, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorszewska, J.; Kozubski, W.; Waleszczyk, W.; Zabel, M.; Ong, K. Neuroplasticity in the Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neural Plast. 2020, 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Prabhakar, M.; Kumar, P.; Deshmukh, R.; Sharma, P.L. Excitotoxicity: Bridge to various triggers in neurodegenerative disorders. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 698, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.G. Concepts and classification of neurodegenerative diseases. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Moehl, K.; Ghena, N.; Schmaedick, M.; Cheng, A. Intermittent metabolic switching, neuroplasticity and brain health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Hamilton, J.L.; Kopil, C.; Beck, J.C.; Tanner, C.M.; Albin, R.L.; Ray Dorsey, E.; Dahodwala, N.; Cintina, I.; Hogan, P.; et al. Current and projected future economic burden of Parkinson’s disease in the U.S. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, G.; Fratila, O.; Buhas, C.; Judea-Pusta, C.T.; Negrut, N.; Bustea, C.; Bungau, S. Cross-talks among GBA mutations, glucocerebrosidase, and α-synuclein in GBA-associated Parkinson’s disease and their targeted therapeutic approaches: A comprehensive review. Transl. Neurodegener. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dues, D.J.; Moore, D.J. LRRK2 and Protein Aggregation in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights From Animal Models. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Behl, T.; Bungau, S.; Kumar, A.; Uddin, M.S.; Mehta, V.; Zengin, G.; Mathew, B.; Shah, M.A.; Arora, S. Dysregulation of the Gut-Brain Axis, Dysbiosis and Influence of Numerous Factors on Gut Microbiota Associated Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 19, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, J.A.S.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Zuardi, A.W.; Guimarães, F.S.; Tumas, V.; dos Santos, R.G. Is cannabidiol the ideal drug to treat non-motor Parkinson’s disease symptoms? Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 269, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, E.J.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Y.; Liu, R.; Huang, X.; Ciesielski-Jones, A.J.; Justice, M.A.; Cousins, D.S.; Peddada, S. Meta-analyses on prevalence of selected Parkinson’s nonmotor symptoms before and after diagnosis. Transl. Neurodegener. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, G.; Bungau, S.; Jhanji, R.; Kumar, A.; Mehta, V.; Zengin, G.; Brata, R.; Hassan, S.S.U.; Fratila, O. Distinctive Evidence Involved in the Role of Endocannabinoid Signalling in Parkinson’s Disease: A Perspective on Associated Therapeutic Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.T.; Uddin, M.S.; Zaman, S.; Begum, Y.; Ashraf, G.M.; Bin-Jumah, M.N.; Bungau, S.G.; Mousa, S.A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Molecular Mechanisms of Metal Toxicity in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 58, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, I.; Fratila, O.; Brata, R.; Bungau, S. Exploring the Potential of Therapeutic Agents Targeted towards Mitigating the Events Associated with Amyloid-beta Cascade in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, I.; Sehgal, A.; Kumar, A.; Uddin, M.S.; Bungau, S. The Interplay of ABC Transporters in A beta Translocation and Cholesterol Metabolism: Implicating Their Roles in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, S.; Behl, T.; Sehgal, A.; Kumar, A.; Bungau, S. Exploring the role of mitochondrial proteins as molecular target in Alzheimer’s disease. Mitochondrion 2021, 56, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, C.; Tan, Z.; Zhai, L.; Hao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Han, C. New mechanism of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: The activation of NLRP3 inflammasome mediated by gut microbiota. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 100, 109884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.S.; Kabir, M.T.; Tewari, D.; Al Mamun, A.; Barreto, G.E.; Bungau, S.G.; Bin-Jumah, M.N.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Ashraf, G.M. Emerging Therapeutic Promise of Ketogenic Diet to Attenuate Neuropathological Alterations in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroni, E.; Bohrmann, B.; Grueninger, F.; Prinssen, E.; Nave, S.; Loetscher, H.; Chinta, S.J.; Rajagopalan, S.; Rane, A.; Siddiqui, A.; et al. Sembragiline: A Novel, Selective Monoamine Oxidase Type B Inhibitor for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 362, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, L.; Mao, C.; Hu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Sun, H.; Fan, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yang, J.; et al. New Insights Into the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, L.G. Alzheimer Disease. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2016, 22, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van den Bos, M.A.J.; Geevasinga, N.; Higashihara, M.; Menon, P.; Vucic, S. Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of ALS: Insights from Advances in Neurophysiological Techniques. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nishiyama, A.; Warita, H.; Takahashi, T.; Suzuki, N.; Nishiyama, S.; Tano, O.; Akiyama, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Kuroda, H.; et al. Prominent sensory involvement in a case of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis carrying the L8V SOD1 mutation. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2016, 150, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, S.; Orrell, R.W. Pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Br. Med. Bull. 2016, 119, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prasad, A.; Bharathi, V.; Sivalingam, V.; Girdhar, A.; Patel, B.K. Molecular Mechanisms of TDP-43 Misfolding and Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Sanchez, M.; Licitra, F.; Underwood, B.R.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Huntington’s Disease: Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Strategies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 7, a024240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Owen Pickrell, W.; Robertson, N.P. Stem cell treatment for multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 2145–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanken, K.; Sander, C.; Qaiser, L.; Schlake, H.P.; Kastrup, A.; Haupts, M.; Eling, P.A.T.M.; Hildebrandt, H. Salivary IL-1ß as an objective measure for fatigue in multiple sclerosis? In Multiple Sclerosis—From Bench to Bedside: Currents Insights into Pathophysiological Concepts and Their Potential Impact on Patients; Rommer, P.S., Weber, M.S., Illes, Z., Eds.; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.A.; Roqué, P.J.; Goverman, J.M. Pathogenic T cell cytokines in multiple sclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative Stress: A Key Modulator in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, M.; Jiang, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases and drug targets via apoptotic signaling. Mitochondrion 2019, 49, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armada-Moreira, A.; Gomes, J.I.; Pina, C.C.; Savchak, O.K.; Gonçalves-Ribeiro, J.; Rei, N.; Pinto, S.; Morais, T.P.; Martins, R.S.; Ribeiro, F.F.; et al. Going the Extra (Synaptic) Mile: Excitotoxicity as the Road Toward Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.; Mangani, A.S.; Gupta, V.; Chitranshi, N.; Shen, T.; Dheer, Y.; Kb, D.; Mirzaei, M.; You, Y.; Graham, S.L.; et al. Cell Cycle Deficits in Neurodegenerative Disorders: Uncovering Molecular Mechanisms to Drive Innovative Therapeutic Development. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.-H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: The roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, R.; Chaudhry, G.-E.-S. Understanding Apoptosis and Apoptotic Pathways Targeted Cancer Therapeutics. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattson, M.P. Apoptosis in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pinilla, E.; Ordóñez, C.; del Valle, E.; Navarro, A.; Tolivia, J. Regional and Gender Study of Neuronal Density in Brain during Aging and in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Albrecht, S.; Bourdeau, M.; Petzke, T.; Bergeron, C.; LeBlanc, A.C. Active Caspase-6 and Caspase-6-Cleaved Tau in Neuropil Threads, Neuritic Plaques, and Neurofibrillary Tangles of Alzheimer’s Disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 165, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masliah, E.; Mallory, M.; Alford, M.; Tanaka, S.; Hansen, L.A. Caspase Dependent DNA Fragmentation Might Be Associated with Excitotoxicity in Alzheimer Disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1998, 57, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A.; Michel, P.P.; Troadec, J.-D.; Mouatt-Prigent, A.; Faucheux, B.A.; Ruberg, M.; Agid, Y.; Hirsch, E.C. Is Bax a mitochondrial mediator in apoptotic death of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease? J. Neurochem. 2001, 76, 1785–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, K.; Mahlke, J.; Siswanto, S.; Krüger, R.; Heinsen, H.; Auburger, G.; Bouzrou, M.; Grinberg, L.T.; Wicht, H.; Korf, H.-W.; et al. The Brainstem Pathologies of Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Brain Pathol. 2014, 25, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, J.C.; Daigle, J.G.; Arbez, N.; Cunningham, K.C.; Zhang, K.; Ochaba, J.; Geater, C.; Morozko, E.; Stocksdale, J.; Glatzer, J.C.; et al. Mutant Huntingtin Disrupts the Nuclear Pore Complex. Neuron 2017, 94, 93–107.e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsuiji, H.; Inoue, I.; Takeuchi, M.; Furuya, A.; Yamakage, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Koike, M.; Hattori, M.; Yamanaka, K. TDP-43 accelerates age-dependent degeneration of interneurons. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vogt, M.A.; Ehsaei, Z.; Knuckles, P.; Higginbottom, A.; Helmbrecht, M.S.; Kunath, T.; Eggan, K.; Williams, L.A.; Shaw, P.J.; Wurst, W.; et al. TDP-43 induces p53-mediated cell death of cortical progenitors and immature neurons. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Central Nervous System Disorders. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 37, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Zucca, P.; Varoni, E.M.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Tsouh Fokou, P.V.; Azzini, E.; Peluso, I.; et al. Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheignon, C.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Boyd-Kimball, D. Oxidative Stress, Amyloid-β Peptide, and Altered Key Molecular Pathways in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 1345–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kikuchi, A.; Takeda, A.; Onodera, H.; Kimpara, T.; Hisanaga, K.; Sato, N.; Nunomura, A.; Castellani, R.J.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; et al. Systemic Increase of Oxidative Nucleic Acid Damage in Parkinson’s Disease and Multiple System Atrophy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 9, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; Robertson, D.; Olson, S.J.; Graham, D.G.; Montine, T.J. Parkinson’s Disease Is Associated with Oxidative Damage to Cytoplasmic DNA and RNA in Substantia Nigra Neurons. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 154, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Otero, R.; Méndez-Álvarez, E.; Hermida-Ameijeiras, Á.; Muñoz-Patiño, A.M.; Labandeira-Garcia, J.L. Autoxidation and Neurotoxicity of 6-Hydroxydopamine in the Presence of Some Antioxidants. J. Neurochem. 2002, 74, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, H.; Choong, C.-J.; Baba, K. Parkinson’s disease and iron. J. Neural Transm. 2020, 127, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha-Oliveira, T.; Montezinho, L.; Mendes, C.; Firuzi, O.; Saso, L.; Oliveira, P.J.; Silva, F.S.G. Oxidative Stress in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Pathophysiology and Opportunities for Pharmacological Intervention. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5021694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohl, K.; Tenbrock, K.; Kipp, M. Oxidative stress in multiple sclerosis: Central and peripheral mode of action. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 277, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Ratan, R.R. Oxidative Stress and Huntington’s Disease: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. J. Huntingt. Dis. 2016, 5, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tellez-Nagel, I.; Johnson, A.B.; Terry, R.D. Studies on brain biopsies of patients with huntington’s chorea. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1974, 33, 308–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Liu, H.; Shi, X.-J.; Cheng, Y. Blood Oxidative Stress Marker Aberrations in Patients with Huntington’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis Study. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 9187195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojda, U.; Salinska, E.; Kuznicki, J. Calcium ions in neuronal degeneration. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhoury, M. Role of Immunity and Inflammation in the Pathophysiology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurodegener. Dis. 2015, 15, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, E.B.; Kurshan, P.T. All Talk, No Assembly: Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels Do Not Mediate Active Zone Formation. Neuron 2020, 107, 593–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wei, H. Calcium Dysregulation in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Target for New Drug Development. J. Alzheimers Dis. Parkinsonism 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichick, S.V.; McGrath, K.M.; Caraveo, G. The role of Ca2+ signaling in Parkinson’s disease. Dis. Models Mech. 2017, 10, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vosler, P.S.; Brennan, C.S.; Chen, J. Calpain-Mediated Signaling Mechanisms in Neuronal Injury and Neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2008, 38, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Estrada Sánchez, A.M.; Mejía-Toiber, J.; Massieu, L. Excitotoxic Neuronal Death and the Pathogenesis of Huntington’s Disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2008, 39, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal-Price, A.; Matthias, A.; Brown, G.C. Stimulation of the NADPH oxidase in activated rat microglia removes nitric oxide but induces peroxynitrite production. J. Neurochem. 2002, 80, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mander, P.K.; Jekabsone, A.; Brown, G.C. Microglia Proliferation Is Regulated by Hydrogen Peroxide from NADPH Oxidase. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Segal, A.W. The function of the NADPH oxidase of phagocytes and its relationship to other NOXs in plants, invertebrates, and mammals. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, G.C. Mechanisms of inflammatory neurodegeneration: INOS and NADPH oxidase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1119–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jorda, A.; Campos-Campos, J.; Iradi, A.; Aldasoro, M.; Aldasoro, C.; Vila, J.M.; Valles, S.L. The Role of Chemokines in Alzheimer’s Disease. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2020, 20, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Won, S.J.; Fabian, C.; Kang, M.-G.; Szardenings, M.; Shin, M.-G. Mitochondrial DNA Aberrations and Pathophysiological Implications in Hematopoietic Diseases, Chronic Inflammatory Diseases, and Cancers. Ann. Lab. Med. 2015, 35, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorziello, A.; Borzacchiello, D.; Sisalli, M.J.; Di Martino, R.; Morelli, M.; Feliciello, A. Mitochondrial Homeostasis and Signaling in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, F.; Ma, X.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calió, M.L.; Henriques, E.; Siena, A.; Bertoncini, C.R.A.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Rosenstock, T.R. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Neurogenesis, and Epigenetics: Putative Implications for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Neurodegeneration and Treatment. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht-Mayer, S.; Campbell, G.R.; Canizares, M.; Mehta, A.R.; Gane, A.B.; McGill, K.; Ghosh, A.; Fullerton, A.; Menezes, N.; Dean, J.; et al. Enhanced axonal response of mitochondria to demyelination offers neuroprotection: Implications for multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2020, 140, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, C.; Tang, Y.; Anjo, S.I.; Manadas, B.; Onofre, I.; de Almeida, L.P.; Daley, G.Q.; Schlaeger, T.M.; Rego, A.C.C. Mitochondrial and Redox Modifications in Huntington Disease Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Rescued by CRISPR/Cas9 CAGs Targeting. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Nie, S. Targeting prion-like protein spreading in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, E.K. Nutraceutical-definition and introduction. AAPS Pharmsci 2003, 5, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chao, J.; Leung, Y.; Wang, M.; Chang, R.C.-C. Nutraceuticals and their preventive or potential therapeutic value in Parkinson’s disease. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.B. Can we put IJGP on the track? Int. J. Green Pharm. 2009, 3, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsha, I.; Raut, H.; Geeta, N.; Lodhi, G.; Deepika, P.; Kalode, D. A general review on nutraceuticals: Its golden health impact over human community. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 9, 1121–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroopa, G. Nutraceuticals and their Health Benefits. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2017, 5, 1151–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nema, V.; Dhas, Y.; Banerjee, J.; Mishra, N. Phytochemicals: An Alternate Approach Towards Various Disease Management. In Functional Food and Human Health; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 623–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallag, A.; Bungau, S.; Tit, D.M.; Jurca, T.; Sirbu, V.; Honiges, A.; Horhogea, C. Comparative Study of Polyphenols, Flavonoids and Chlorophylls in Equisetum arvense L. Populations. Rev. Chim. 2016, 67, 530–533. [Google Scholar]

- Bungau, S.G.; Popa, V.-C. Between Religion and Science Some Aspects Concerning Illness and Healing in Antiquity. Transylv. Rev. 2015, 24, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrmann, D.D.; Putnik, P.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J. Japanese, Mediterranean and Argentinean diets and their potential roles in neurodegenerative diseases. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barba, F.J.; Putnik, P.; Bursać Kovačević, D. Preface. In Agri-Food Industry Strategies for Healthy Diets and Sustainability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. xiii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnik, P.; Gabrić, D.; Roohinejad, S.; Barba, F.J.; Granato, D.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Bursać Kovačević, D. Bioavailability and food production of organosulfur compounds from edible Allium species. In Innovative Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing, Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, L.; Bhaumik, E.; Raychaudhuri, U.; Chakraborty, R. Role of nutraceuticals in human health. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 49, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ganguly, R.; Lytwyn, M.; Pierce, G. Differential Effects of Trans and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Ischemia/ Reperfusion Injury and its Associated Cardiovascular Disease States. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 6858–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khinchi, M.P.; Khan, M.S.; Saluja, S.S. Coronavirus Pandemic: Emergence, Transmission, Preventive Measures and Management. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 1970, 8, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George Kerry, R.; Patra, J.K.; Gouda, S.; Park, Y.; Shin, H.-S.; Das, G. Benefaction of probiotics for human health: A review. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tapal, A.; Tiku, P.K. Nutritional and Nutraceutical Improvement by Enzymatic Modification of Food Proteins. In Enzymes in Food Biotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Yadav, R. Bronchial asthma: A global health problem. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Abushouk, A.I.; Donia, T.; Alarifi, S.; Alkahtani, S.; Aleya, L.; Bungau, S.G. The nephroprotective effects of allicin and ascorbic acid against cisplatin-induced toxicity in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 13502–13509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Ahmed, A.; Ijaz, H.; Abushouk, A.I.; Ahmed, H.; Negida, A.; Aleya, L.; Bungau, S.G. Influence of Spirulina platensis and ascorbic acid on amikacin-induced nephrotoxicity in rabbits. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 8080–8086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry Ottaway, P. Principles of food fortification and supplementation. In Food Fortification and Supplementation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, A. Food as pharma: Marketing nutraceuticals to India’s rural poor. Crit. Public Health 2014, 25, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aronson, J.K. Defining ‘nutraceuticals’: Neither nutritious nor pharmaceutical. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 83, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosálbez, L.; Ramón, D. Probiotics in transition: Novel strategies. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andlauer, W.; Fürst, P. Nutraceuticals: A piece of history, present status and outlook. Food Res. Int. 2002, 35, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P. Clinician’s perspective on the dietary supplement health and education act of 1994’s (DSHEA) ability to ensure the safety of dietary supplements. Planta Med. 2015, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Enhanced delivery of lipophilic bioactives using emulsions: A review of major factors affecting vitamin, nutraceutical, and lipid bioaccessibility. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kumar, K.; Brisc, C.; Rus, M.; Nistor-Cseppento, D.C.; Bustea, C.; Aron, R.A.C.; Pantis, C.; Zengin, G.; Sehgal, A.; et al. Exploring the multifocal role of phytochemicals as immunomodulators. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, M.J.; Johnson, D.A.; Townsend, J.A.; Vargas, M.R.; Dowell, J.A.; Williamson, T.P.; Kraft, A.D.; Lee, J.-M.; Li, J.; Johnson, J.A. The Nrf2/ARE Pathway as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Neurodegenerative Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kraft, A.D. Nuclear Factor E2-Related Factor 2-Dependent Antioxidant Response Element Activation by tert-Butylhydroquinone and Sulforaphane Occurring Preferentially in Astrocytes Conditions Neurons against Oxidative Insult. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schepici, G.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. Efficacy of Sulforaphane in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.J.; Torricelli, J.R.; Lindsey, A.L.; Kunz, E.Z.; Neuman, A.; Fisher, D.R.; Joseph, J.A. Age-related toxicity of amyloid-beta associated with increased pERK and pCREB in primary hippocampal neurons: Reversal by blueberry extract. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalt, W.; Cassidy, A.; Howard, L.R.; Krikorian, R.; Stull, A.J.; Tremblay, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. Recent Research on the Health Benefits of Blueberries and Their Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Sun, Z.; Han, X.; Li, S.; Jiang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Lu, H. Neuroprotective Effect of Resveratrol via Activation of Sirt1 Signaling in a Rat Model of Combined Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taram, F.; Ignowski, E.; Duval, N.; Linseman, D. Neuroprotection Comparison of Rosmarinic Acid and Carnosic Acid in Primary Cultures of Cerebellar Granule Neurons. Molecules 2018, 23, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peng, Q.L.; Buz’Zard, A.R.; Lau, B.H.S. Pycnogenol® protects neurons from amyloid-β peptide-induced apoptosis. Mol. Brain Res. 2002, 104, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuto, H.; Tada, M.; Kohno, M. Eugenol [2-Methoxy-4-(2-propenyl)phenol] Prevents 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Dopamine Depression and Lipid Peroxidation Inductivity in Mouse Striatum. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, K.H.; Cha, M.; Lee, B.H. Neuroprotective Effect of Antioxidants in the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rahbi, B.; Zakaria, R.; Othman, Z.; Hassan, A.; Mohd Ismail, Z.I.; Muthuraju, S. Tualang honey supplement improves memory performance and hippocampal morphology in stressed ovariectomized rats. Acta Histochem. 2014, 116, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, K.F.; Zakaria, R.; Abdul Aziz, C.B.; Othman, Z. Tualang Honey Attenuates Noise Stress-Induced Memory Deficits in Aged Rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1549158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar Saxena, A.; Phyu, H.P.; Al-Ani, I.M.; Oothuman, P. Improved spatial learning and memory performance following Tualang honey treatment during cerebral hypoperfusion-induced neurodegeneration. J. Transl. Sci. 2016, 2, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dar, N.J.; Muzamil, A. Neurodegenerative diseases and Withania somnifera (L.): An update. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 256, 112769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, P.; Cui, R. Effects of Ginseng on Neurological Disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagheri, H.; Ghasemi, F.; Barreto, G.E.; Rafiee, R.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of curcumin on mitochondria in neurodegenerative diseases. BioFactors 2019, 46, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, S.M.; Romeiro, C.F.R.; Rodrigues, C.A.; Cerqueira, A.R.L.; Monteiro, M.C. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Beneficial or Harmful in Alzheimer’s Disease? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.-H. Astaxanthin Inhibits H2O2-Mediated Apoptotic Cell Death in Mouse Neural Progenitor Cells via Modulation of P38 and MEK Signaling Pathways. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-P.; Liu, S.-Y.; Sun, H.; Wu, X.-M.; Li, J.-J.; Zhu, L. Neuroprotective effect of astaxanthin on H2O2-induced neurotoxicity in vitro and on focal cerebral ischemia in vivo. Brain Res. 2010, 1360, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleren, C.; Yang, L.; Lorenzo, B.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Schomer, A.; Sireci, A.; Wille, E.J.; Beal, M.F. Therapeutic effects of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) and reduced CoQ10 in the MPTP model of Parkinsonism. J. Neurochem. 2007, 104, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, A.; Jost, W.; Vieregge, P.; Spiegel, J.; Greulich, W.; Durner, J.; Müller, T.; Kupsch, A.; Henningsen, H.; Oertel, W.H.; et al. Multizentrische, plazebokontrollierte, randomisierte Doppelblindstudie: Coenzym Q10-Nanodispersion versus Plazebo zur symptomatischen Therapie von Patienten mit Morbus Parkinson. Aktuelle Neurol. 2005, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisardi, V.; Panza, F.; Solfrizzi, V.; Seripa, D.; Pilotto, A. Plasma lipid disturbances and cognitive decline. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 2429–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.Y.; Xu, J.; Jensen, M.D.; Simonyi, A. Phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eghbaliferiz, S.; Farhadi, F.; Barreto, G.E.; Majeed, M.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of curcumin on neurological diseases: Focus on astrocytes. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, K.; Barthelmes, J.; Stolz, L.; Beyer, S.; Diehl, O.; Tegeder, I. “Disease modifying nutricals” for multiple sclerosis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 148, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, Y.D.; Stoney, P.N.; McCaffery, P.J. The Evidence for a Beneficial Role of Vitamin A in Multiple Sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2014, 28, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianforcaro, A.; Hamadeh, M.J. Vitamin D as a Potential Therapy in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2014, 20, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, L.; Wang, G.; Liou, A.K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Leak, R.K.; Wang, Y.; et al. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation Improves Neurologic Recovery and Attenuates White Matter Injury after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jang, M.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, C.S.; Cho, I.-H. Korean Red Ginseng Extract Attenuates 3-Nitropropionic Acid-Induced Huntington’s-Like Symptoms. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 237207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.; Liu, Z.; Sun, W.; Yuan, Y.; Jiao, B.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L.; Jiang, H.; Xia, K.; Tang, B.; et al. Association Between Vitamins and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Center-Based Survey in Mainland China. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sairazi, N.S.; Sirajudeen, K.N.S.; Muzaimi, M.; Mummedy, S.; Asari, M.A.; Sulaiman, S.A. Tualang Honey Reduced Neuroinflammation and Caspase-3 Activity in Rat Brain after Kainic Acid-Induced Status Epilepticus. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 7287820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swamy, M.; Norlina, W.; Azman, W.; Suhaili, D.; Sirajudeen, K.N.S.; Mustapha, Z.; Govindasamy, C. Restoration Of Glutamine Synthetase Activity, Nitric Oxide Levels And Amelioration Of Oxidative Stress By Propolis In Kainic Acid Mediated Excitotoxicity. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swamy, M.; Suhaili, D.; Sirajudeen, K.N.S.; Mustapha, Z.; Govindasamy, C. Propolis Ameliorates Tumor Nerosis Factor-α, Nitric Oxide levels, Caspase-3 and Nitric Oxide Synthase Activities in Kainic Acid Mediated Excitotoxicity in Rat Brain. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, J.-M.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. Ginseng Compounds: An Update on their Molecular Mechanisms and Medical Applications. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2009, 7, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryu, S.; Koo, S.; Ha, K.-T.; Kim, S. Neuroprotective effect of Korea Red Ginseng extract on 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced apoptosis in PC12 Cells. Anim. Cells Syst. 2016, 20, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shim, J.S.; Kim, H.G.; Ju, M.S.; Choi, J.G.; Jeong, S.Y.; Oh, M.S. Effects of the hook of Uncaria rhynchophylla on neurotoxicity in the 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 126, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Alves, C.; Pinteus, S.; Mendes, S.; Pedrosa, R. Neuroprotective effects of seaweeds against 6-hydroxidopamine-induced cell death on an in vitro human neuroblastoma model. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heo, S.-J.; Cha, S.-H.; Kim, K.-N.; Lee, S.-H.; Ahn, G.; Kang, D.-H.; Oh, C.; Choi, Y.-U.; Affan, A.; Kim, D.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect of Phlorotannin Isolated from Ishige okamurae Against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in Murine Hippocampal Neuronal Cells, HT22. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 166, 1520–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Betti, G.; Hensel, A. Saffron in phytotherapy: Pharmacology and clinical uses. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2007, 157, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, G. Crocin protects PC12 cells against MPP+-induced injury through inhibition of mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.X.; Xie, W.; Le, W.; Fan, Z.; Jankovic, J.; Pan, T. Resveratrol-Activated AMPK/SIRT1/Autophagy in Cellular Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosignals 2011, 19, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz; Williamson. Interactions Affecting the Bioavailability of Dietary Polyphenols in Vivo. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2007, 77, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Yoshioka, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Murakami, M.; Noya, M.; Takahashi, D.; Urashima, M. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation in Parkinson disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lau, L.M.L.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M.B. Dietary folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin B6 and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology 2006, 67, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Miyake, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Tanaka, K.; Fukushima, W.; Kiyohara, C.; Tsuboi, Y.; Yamada, T.; Oeda, T.; Miki, T.; et al. Dietary intake of folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and riboflavin and risk of Parkinson’s disease: A case–control study in Japan. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gualano, B.; Artioli, G.G.; Poortmans, J.R.; Lancha Junior, A.H. Exploring the therapeutic role of creatine supplementation. Amino Acids 2009, 38, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, C.A.; Ernst, M.E. Antioxidants, Supplements, and Parkinson’s Disease. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006, 40, 935–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Aleya, L.; El-Bialy, B.E.; Abushouk, A.I.; Alkahtani, S.; Alarifi, S.; Alkahtane, A.A.; AlBasher, G.; Ali, D.; Almeer, R.S.; et al. The ameliorative effects of ceftriaxone and vitamin E against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K.; Ghosh, D.; Basu, A. Curcumin Protects Neuronal Cells from Japanese Encephalitis Virus-Mediated Cell Death and also Inhibits Infective Viral Particle Formation by Dysregulation of Ubiquitin–Proteasome System. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009, 4, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, R.K.; Rajagopal, V.; Kalra, V.K. Curcumin, the active constituent of turmeric, inhibits amyloid peptide-induced cytochemokine gene expression and CCR5-mediated chemotaxis of THP-1 monocytes by modulating early growth response-1 transcription factor. J. Neurochem. 2004, 91, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBasher, G.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Almeer, R.; Ibrahim, K.A.; Hamza, R.Z.; Bungau, S.; Aleya, L. Synergistic antioxidant effects of resveratrol and curcumin against fipronil-triggered oxidative damage in male albino rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 6505–6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKahtane, A.A.; Ghanem, E.; Bungau, S.G.; Alarifi, S.; Ali, D.; AlBasher, G.; Alkahtani, S.; Aleya, L.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Carnosic acid alleviates chlorpyrifos-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in mice cerebral and ocular tissues. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 11663–11670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, J.-l.; Wang, Y.-r.; Fa, X.-z. Apigenin attenuates copper-mediated β-amyloid neurotoxicity through antioxidation, mitochondrion protection and MAPK signal inactivation in an AD cell model. Brain Res. 2013, 1492, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-B.; Lee, H.J.; Won, M.H.; Hwang, I.K.; Kang, T.-C.; Lee, J.-Y.; Nam, S.-Y.; Kim, K.-S.; Kim, E.; Cheon, S.-H.; et al. Soy Isoflavones Improve Spatial Delayed Matching-to-Place Performance and Reduce Cholinergic Neuron Loss in Elderly Male Rats. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1827–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarozzi, A.; Angeloni, C.; Malaguti, M.; Morroni, F.; Hrelia, S.; Hrelia, P. Sulforaphane as a potential protective phytochemical against neurodegenerative diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 415078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Park, G.H.; Lee, S.-R.; Jang, J.-H. Attenuation of-amyloid-induced oxidative cell death by sulforaphane via activation of NF-E2-related factor 2. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 313510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rezlescu, E.; Rezlescu, N.; Popa, P.D.; Rezlescu, L. Some aspects concerning dielectric behaviour of copper containing magnetic ceramics. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Electrets (ISE 10), Proceedings (Cat. No.99 CH36256), Athens, Greece, 22–24 September 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Betti, M.; Minelli, A.; Ambrogini, P.; Ciuffoli, S.; Viola, V.; Galli, F.; Canonico, B.; Lattanzi, D.; Colombo, E.; Sestili, P. Dietary supplementation with α-tocopherol reduces neuroinflammation and neuronal degeneration in the rat brain after kainic acid-induced status epilepticus. Free Radic. Res. 2011, 45, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisen, P.S.; Schneider, L.S.; Sano, M.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Van Dyck, C.H.; Weiner, M.F.; Bottiglieri, T.; Jin, S.; Stokes, K.T.; Thomas, R.G. High-dose B vitamin supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008, 300, 1774–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.; Wengreen, H.; Munger, R.; Corcoran, C. Dietary folate, vitamin B-12, vitamin B-6 and incident Alzheimer’s disease: The cache county memory, health, and aging study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datla, K.P.; Zbarsky, V.; Rai, D.; Parkar, S.; Osakabe, N.; Aruoma, O.I.; Dexter, D.T. Short-term supplementation with plant extracts rich in flavonoids protect nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P.; Montes, P.; Rojas, C.; Serrano-García, N.; Rojas-Castañeda, J.C. Effect of a phytopharmaceutical medicine, Ginko biloba extract 761, in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease: Therapeutic perspectives. Nutrition 2012, 28, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba, J.; Dibarrart, A.J.; Fuentes-Fuentes, M.C.; Saez-Orellana, F.; Quiñones, K.; Guzmán, L.; Perez, C.; Becerra, J.; Aguayo, L.G. Synaptic failure and adenosine triphosphate imbalance induced by amyloid-β aggregates are prevented by blueberry-enriched polyphenols extract. J. Neurosci. Res. 2011, 89, 1499–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.S.; Goad, D.L.; Grillo, M.A.; Kaja, S.; Payne, A.J.; Koulen, P. Control of intracellular calcium signaling as a neuroprotective strategy. Molecules 2010, 15, 1168–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsieh, C.-L.; Chen, M.-F.; Li, T.-C.; Li, S.-C.; Tang, N.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-T.; Pon, C.-Z.; Lin, J.-G. Anticonvulsant effect of Uncaria rhynchophylla (Miq) Jack. in rats with kainic acid-induced epileptic seizure. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1999, 27, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.R.; Moon, H.E.; Kim, H.R.; Jung, H.A.; Choi, J.S. Neuroprotective effect of edible brown alga Eisenia bicyclis on amyloid beta peptide-induced toxicity in PC12 cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2012, 35, 1989–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nutraceuticals | Targeted Mechanism(s) and Pathway(s) | Elicited Effect(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coenzyme Q10 | Preserved functions of mitochondria | Protection against various excitotoxic lesions of striatum generated by the mitochondrial inhibitor (Complex II mitochondrial toxin) and various NDs. | [135,136] |

| Vitamin D3 | - | Stabilizes and alleviates symptoms of PD without stimulating hypercalcemia | [159] |

| L-sulforaphane (isothiocyanate compound) | Inhibition of pro-inflammatory signaling via toll-like receptors or NF-κb and decrease in ROS. | Inhibited neuronal death induced by dopamine quinone and stabilized the BBB in MS. | [118,119] |

| Vitamin D | Anti-inflammatory mechanism | Protective in AD, MS, and PD patients. | [143] |

| Vitamin B6 | Amelioration of PD symptoms | [160,161] | |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, mustard oil (glycoside) | Prevention of pro-inflammatory signaling via NF-κB or toll-like receptors | Stabilized the BBB in MS | [141] |

| Creatine | - | Ameliorates PD symptoms | [162] |

| CoQ10, tocopherol, and GSH | - | Shows a small yet significant betterment in PD symptoms | [163,164] |

| Curcumin | Restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential, suppression of increased intracellular ROS, inhibition of pro-inflammatory signaling via toll-like receptors and NF-κb, decreased malondialdehyde, cytochrome c levels, and cleaved caspase-3 expression | Ameliorated neurotoxicity induced by 6-OHDA in MES23.5 cells, stabilized the BBB in MS, protected SH-SY5Y cells against MPTP-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity or MPP (+) | [132,165,166,167] |

| Astaxanthin | Enhancing production of energy by shielding mitochondria | Protection of cultured nerve cells | [134,135] |

| Carnosic acid and Rosmarinic acid | Scavenging of ROS | Neuroprotective effect in both in vivo models of neurodegeneration and in vitro neuronal death models and protected neuronal cells from oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. | [123,168] |

| Eugenol | Elevated GSH level and reduced 6-OHDA-induced lipid peroxidation | Prevented 6-OHDA induced decrease in the dopamine level in the striatum of mouse | [125] |

| Tert-butyl hydroquinone | Stimulation of Nrf2-ARE transcriptional pathway | Protected astrocytes and neurons against hydrogen peroxide- induced OS | [118] |

| Aged garlic extract | Inhibiting generation of ROS and reduced activation of caspase-3, DNA fragmentation and cleavage of PARP. | Shielded PC12 cells against apoptosis induced by Aβ peptide | [124] |

| Anthocyanins | Negative regulation of pro-oxidants and -inflammatory cytokine signaling pathways | Neuroprotection | [121,139] |

| Apigenin | Stabilized the potential of mitochondrial membrane | Modulated glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission and protected neurons against Aβ-mediated toxicity induced by copper | [169,170] |

| Isothiocyanates (e.g., sulforaphane) | Activate Nrf2/ARE pathway | Promoted the upregulation of GSH, upregulation of antioxidant enzymes through activation of Nrf2, prevention of apoptosis mediated by Aβ | [171,172] |

| Soy isoflavones | Modulation of brain cholinergic system | Amelioration of age-associated cognition decline and neuronal loss in male rats | [173] |

| Vitamin E | Reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β | Reduction in neuronal degeneration and neuroinflammation in the rat brain | [174] |

| Folate, vitamin B6 and B12 | Downregulation of GSK-3β, JNK, ERK, and p38MAPK pathway | Inhibit memory deficits and tau hyperphosphorylation induced by homocysteine administration and decrease memory deficits. | [175,176] |

| Extracts of tangerine peel (rich in polymethoxylated flavones), red clover (rich in isoflavones), and cocoa-2 (rich in procyanidins) | - | Decreases dopaminergic neuronal loss | [177] |

| Ginkgo biloba extract 761 (EGb 761, comprising 6% terpenoids 24% flavonoids) | - | Antioxidant effect, promotes neurorecovery of damaged dopaminergic neurons of midbrain, enhances locomotion | [178] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Behl, T.; Kaur, G.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, S.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Zengin, G.; Bungau, S.G.; Munteanu, M.A.; Brisc, M.C.; et al. Elucidating the Multi-Targeted Role of Nutraceuticals: A Complementary Therapy to Starve Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4045. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22084045

Behl T, Kaur G, Sehgal A, Singh S, Bhatia S, Al-Harrasi A, Zengin G, Bungau SG, Munteanu MA, Brisc MC, et al. Elucidating the Multi-Targeted Role of Nutraceuticals: A Complementary Therapy to Starve Neurodegenerative Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(8):4045. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22084045

Chicago/Turabian StyleBehl, Tapan, Gagandeep Kaur, Aayush Sehgal, Sukhbir Singh, Saurabh Bhatia, Ahmed Al-Harrasi, Gokhan Zengin, Simona Gabriela Bungau, Mihai Alexandru Munteanu, Mihaela Cristina Brisc, and et al. 2021. "Elucidating the Multi-Targeted Role of Nutraceuticals: A Complementary Therapy to Starve Neurodegenerative Diseases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 8: 4045. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms22084045