Transcriptional Activation of Stress Genes and Cytotoxicity in Human Liver Carcinoma (HepG2) Cells Exposed to Pentachlorophenol

Abstract

:Introduction

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Gene Profile and Cytotoxicity Assays

Statistical Analysis

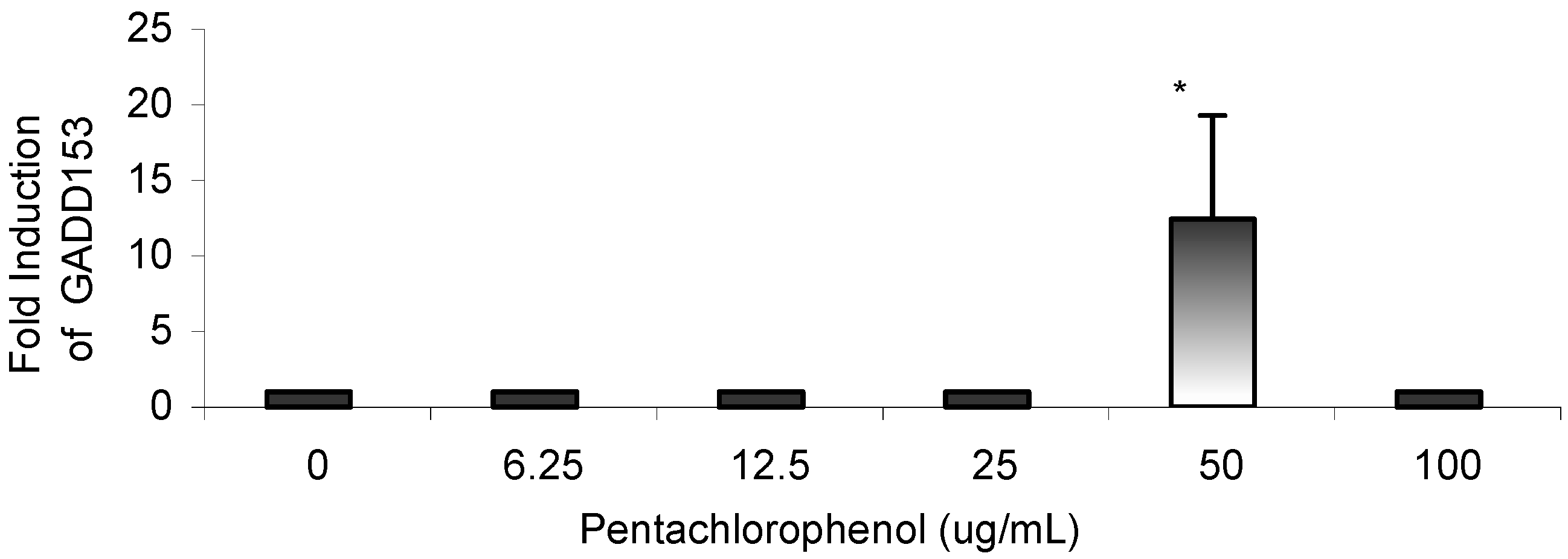

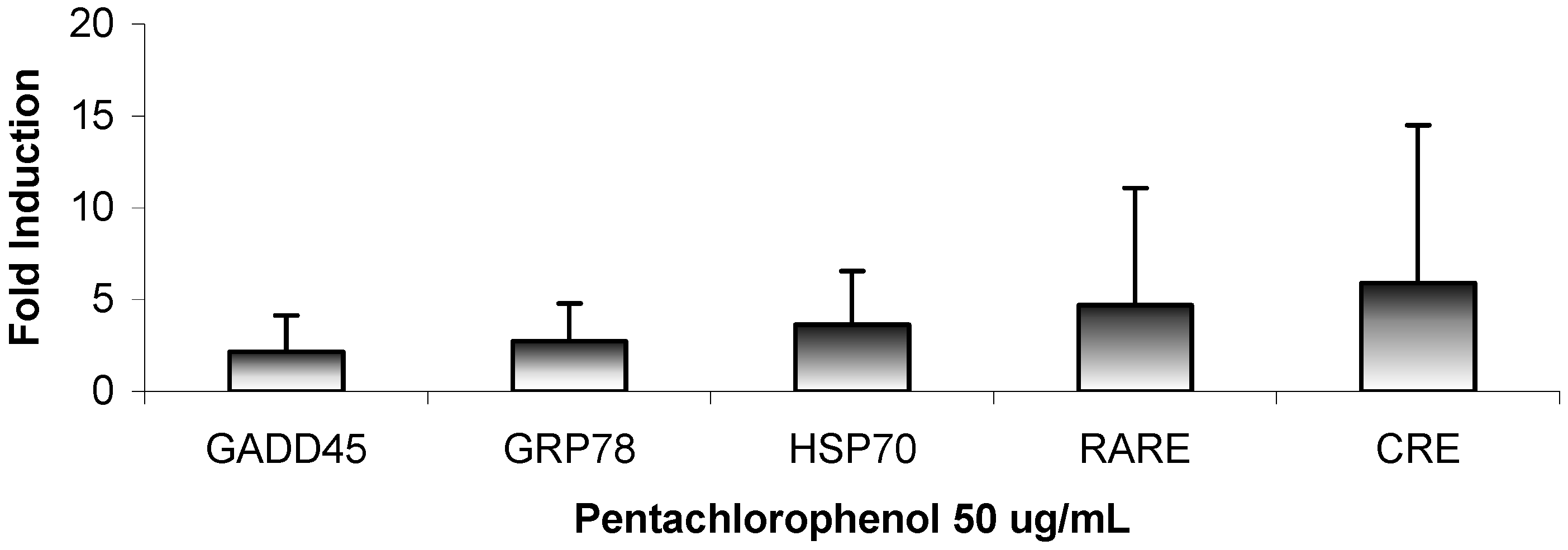

Results

| Phase I Metabolism PAH Induction CYP1A1 | Heavy Metal Sequestration HMTIIA | Growth arrest DNA-Damage GADD153/GADD45 |

| Phase II Metabolism PAH Induction GST YA | Protein Chaperone Heat Induction HSP70 | Binding Site for Retinoic Acid RARE |

| AH Binding Sequence XRE | cAMP Reporter Element CRE | AP-1 Factor Component FOS |

| ER Protein Chaperone GRP78 | Oxidative Stress Mitogen Induction NFkBRE | Programmed Cell Death/ Apoptosis Cell Cycle Arrest p53RE |

Discussion

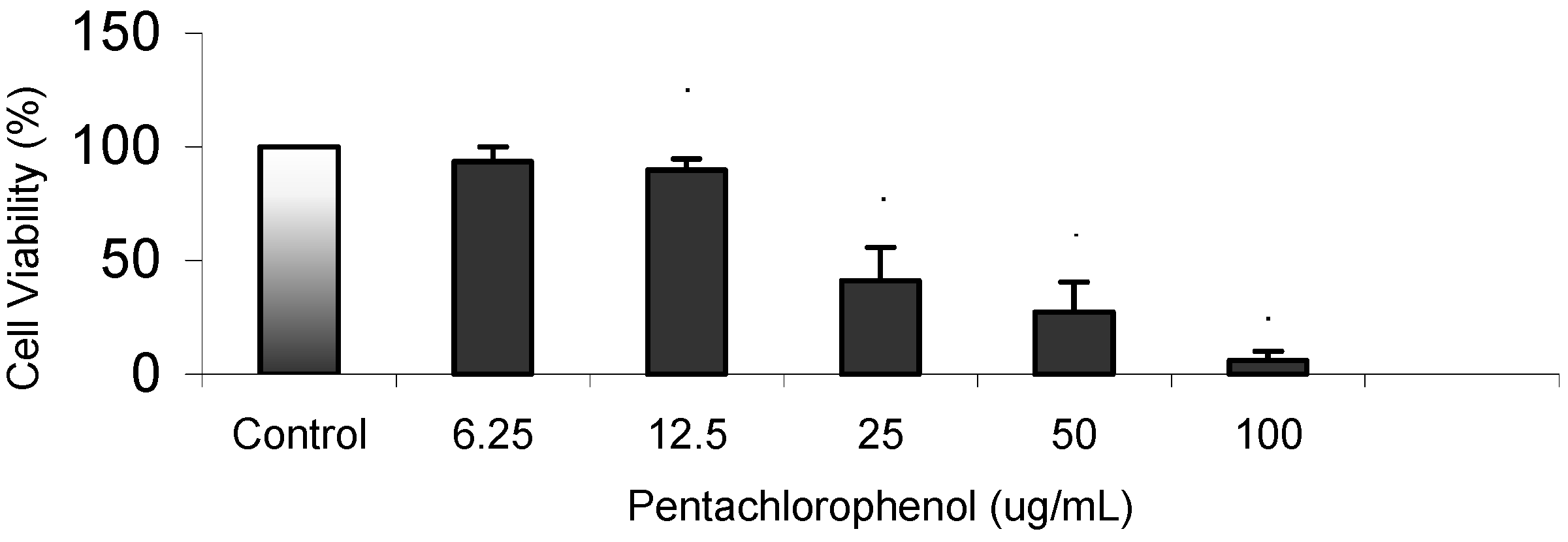

Cytotoxicity Assay

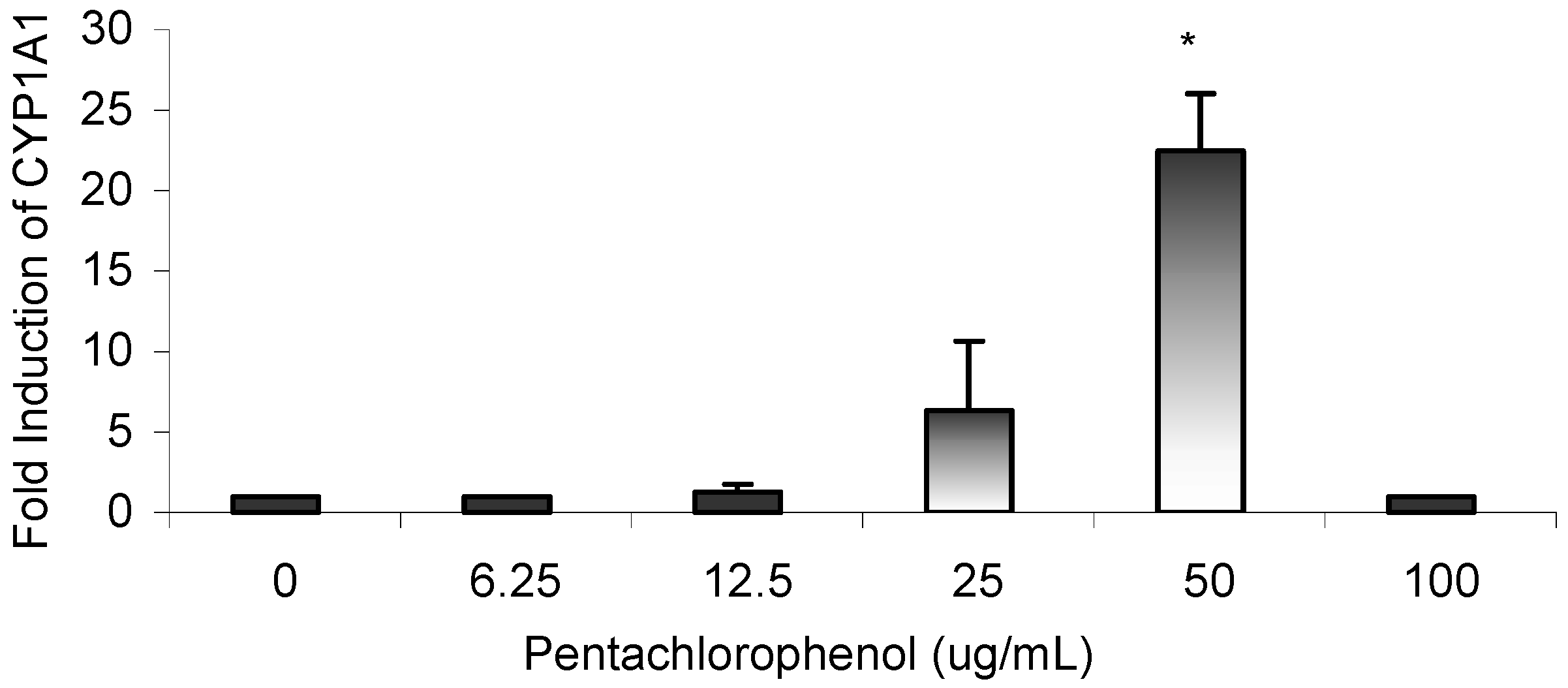

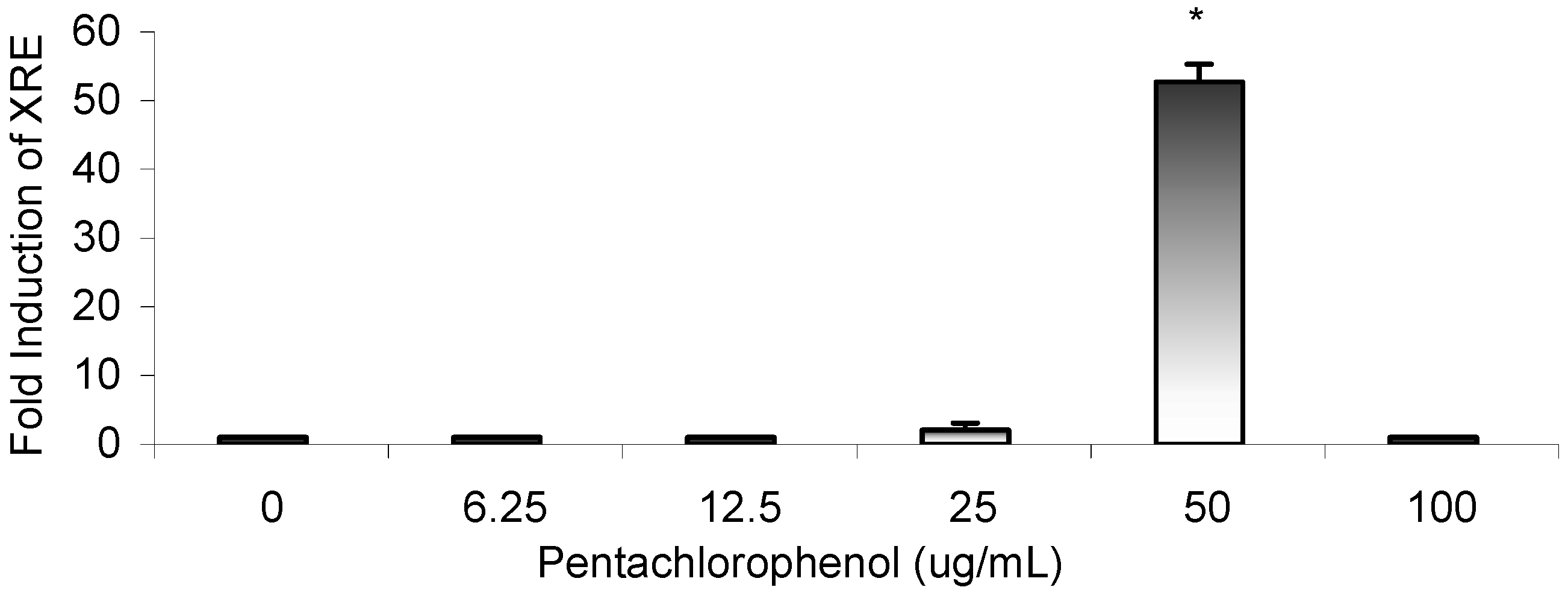

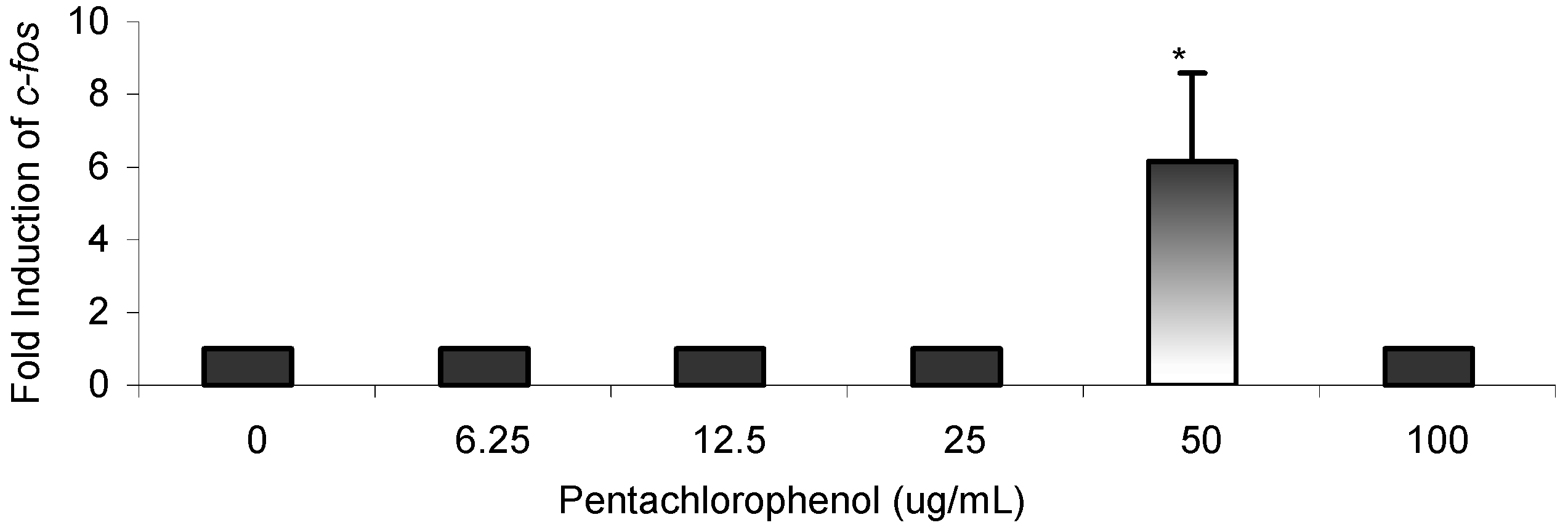

Gene Profile Assay

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Report EPA625R97007. Treatment performance and cost data for remediation of wood preserving sites. Office of Research and Development: Washington, D.C., 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli, D.P. Patterns of pentachlorophenol usage in the United States of America: an overview. In Pentachlorophenol: chemistry, pharmacology, and environmental toxicology; Rao, K.R., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, 1978; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.; Rom, V.N.; White, G.L.; Logan, D.C. Pentachlorophenol poisoning. J. Occup. Med. 1983, 25, 527–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Menzer, R.E.; Nelson, J.O. Water and soil pollutants. In Casarett and Doull’s Toxicology; Klaassen, C.D., Amdur, M.O., Doull, J., Eds.; 3rd ed.; New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1986; pp. 825–853. [Google Scholar]

- Kinzell, J.H.; Ames, N.K.; Sleight, S.D.; Krehbiel, J.D.; Kuo, C.; Zabik, M.J.; Shull, L.R. Subchronic administration of technical pentachlorophenol to lactaing dairy cattle: performance, general health, and pathologic changes. J. Dairy Sci. 1981, 64, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Colosio, C.; Maroni, M.; Barcellini, W.; Meroni, P.; Alcini, D.; Colombi, A.; Foa, V. Toxicological and immune findings in workers exposed to pentachlorophenol (PCP). Arch. Environ. Health 1993, 48(2), 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. National Toxicology Program (NTP). Pentachlorophenol. NTP Chemical Respository Report. Radian Corporation. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Pentachlorophenol. Environmental Health Criteria 71. Geneva, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water (OGWDW). Technical Drinking Water and Health Contaminant Specific Fact Sheet. Technical fact sheet on pentachloro- phenol. 1998. online at: http://www/epa.gov/OGWDW/dwh/tsoc/pentach. [Google Scholar]

- Colborn, T.; vom Saal, F.S.; Soto, A.M. Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environ. Health Perspect. 1993, 101(5), 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Solla, S.R.; Bishop, C.A.; Van Der Kraak, G.; Brooks, R.J. Impact of contamination on levels of sex hormones and external morphology of common snapping turtles (Chelydtra serpentina serpentina) in Ontario, Canada. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998, 106, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meacher, M. Speech to SERA Conference; 25th January 1997.

- Beard, A.P.; Barthlewski, P.M.; Chandolia, R.K.; Honaramooz, A.; Rawlings, N.C. Reproductive and endocrine function in rams exposed to the organochlorine pesticides lindane and PCP from conception. J. Reprod. Fert. 1999, 115, 303–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, A.P.; Bartlewski, P.M.; Rawlings, N.C. Endocrine and reproductive function in ewes exposed to the organochlorine pesticides lindane or penta-chlorophenol. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 1999, 56, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, V.; Wolfgang, H.; Klausdieter, B.; Opelz, G. Impaired in-vitro lymphocyte responses in patients with elevated pentachlorophenol (PCP) blood levels. Arch. Environ. Health 1995, 50, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peper, M.; Ertl, M.; Gerhard, I. Long-term exposure to wood-preserving chemicals containing pentachlorophenol and lindane is related to neurobehavioral performance in women. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1999, 36(6), 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, N.C.; Cook, S..J.; Waldbillig, D. Effects of the pesticides carbofuran, chlorpyrifos, dimehoate, lindane, triallte, triluralin, 2,4-D, and pentachlorophenol on the metabolic endocrine and reproductive endocrine system in ewes. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 1998, 54, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, A.; Rall, D. Environmental medicine: integrating a missing element into medical education. Committee on Curriculum Development in Environmental Medicine. Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press, 1995; 542–555. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatello, J.J.; Martinson, M.M.; Steiert, J.G.; Carlson, R.E.; Crawford, R.L. Biodegradation and photolysis of pentachlorophenol in artificial freshwater streams. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 1024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rugman, F.P.; Cosstick, R. Aplastic anemia associated with organochlorine pesticide: case reports and review of evidence. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000, 43, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extension Toxicology Network (Extoxnet). Pentachlorophenol. Pesticide Information Profile. A Pesticide Information Project of Cooperative Extension Offices of Cornell University, Michigan State University, Oregon State University, and University of California at Davis. 1998. online at: http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extonet/metiram-propoxur/pentachlorophenol-ext.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Toxicological Profile for Pentachlorophenol. Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry; Draft. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding, J.W.; French, J.E.; Stasiewicz, S.; Furedi-Machacek, M.; Conner, F.; Tice, R.R.; and Tennant, R.W. Responses of transgenic mouse lines p53(+/-) and Tg.AC to agents tested in conventional carcinogenicity bioassays. Toxicol. Sci. 2000, 53, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxicological Profile for Pentachlorophenol (Draft). U.S. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) on Pentachlorophenol. Environmental Criteria and Assessment Office, Office of Health and Environmental Assessment, Office of Research and Development: Cincinnati, OH, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Wilson, B.A.; Schneider, J.; Ishaque, A. Cytogenetic assessment of arsenic trioxide toxicity in the Mutatox, Ames II, and CAT-Tox assays. Met. Ions Biol. Med. 2000, 6, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, M.D.; Lee, M.J.; Williams, J.M.; Nalezny, Gee, P.; Benjamin, M.B.; Farr, S.B. The CAT-Tox (L) assay: a sensitive and specific measure of stress- induced transcription in transformed human liver cells. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1995, 28, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: applications to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immun. 1983, 65((1-2)), 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, V.S.; Fitch, C.A.; Levenson, C.W. Tumor suppressor protein p53 mRNA and subcellular localization are altered by changes in cellular copper in human HepG2 cells. J. Nutrit. 2001, 1311, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Wilson, B.A.; Ishaque, A.B.; Schneider, J. Transcriptional activation of stress genes and cytotoxicity in human liver carcinoma cells (HepG2) exposed to 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, 2,4-dinitrotoluene, and 2,6-dinitrotoluene. Environ. Toxicol. 2001, 6, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Takeshita, T.; Takeuchi, T.; Saito, T. Genotoxic effects of alpha-endosulfan and beta-endosulfan on human HepG2 cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 6, 559–561. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, A.M.; Chung, K.L.; Sonnenschein, C. The pesticides endosulfan, toxaphene and dieldrin have estrogenic effects on human estrogen-sensitive cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 1994, 102, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, T.; Mimura, J.; Gradin, K.; Kuroiwa, A.; Watanabe, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Inazawa, J.; Sogawa, K.; Fujii-Kuriyama. Structure and expression of the Ah Receptor Repressor gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 33101–33110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadar, M.D.; Ash, R.; Sundqvist, J.; Olsson, P.E.; Andersson, T.B. Phenobarbital induction of CYP1A1 gene expression in a primary culture of rainbow trout hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 17635–17643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Tukey, R.H. Protein kinase c modulates regulation of the CYP1A1 gene by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 26261–26266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denison, M.S.; Fisher, J.M.; and Whitlock, J.P., Jr. Protein-DNA interactions at recognition sites for the dioxin-Ah receptor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 16478–16482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Imataka, H.; Sogawa, K.; Yasumoto, K.I.; Kikuchi, Y. Regulation of CYP1A1 expression. Fasc Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1992, 6, 706–710. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Y.; Nakayama, K.; Itoh, S.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Kamataki, T. Inhibition of the transcription of CYP1A1 gene by the upstream stimulatory factor in rabbits. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 300025–300031. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, M.C.; Fornace, A.J., Jr. Induction of fos RNA by DNA- damaging agents. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, Y.; Sugamura, K. Involvement of Hgs/Hrs in signaling for cytokine- c-fos induction through interaction with TAK1 and Pak1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 29943–29952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, R.I.; Heguy, A.; Karin, M. Structural and functional analysis of human metallothionein-I gene: Differentiation induction by metal ions and glucocorticoids. Cell 1984, 37, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, L.H.; Tetsunari, F.; Freedman, J.H. Regulation of metallothionein gene transcription. Identification of upstream regulatory elements and transcription factors responsible for cell-specific expression of the metallothionein genes from Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Develop. 1999, 274, 29655–29665. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, C.; Morimoto, R.I. Role of the heat shock response and molecular chaperones in oncogenesis and cell death. J. Nation. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 1564–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haze, K.; Yoshida, H.; Yanagi, H.; Yura, T.; Mori, K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activitated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 3787–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozutsumi., Y.; Segal, M.; Normington, K.; Gething, M.J.; Sambrook, J. The presence of malfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum signals the induction of glucose- regulated proteins. Nature 1988, 332, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooden, S.K.; Li, L.J.; Navarro, D.; Qadri, I.; Pereira, L. Transactivation of the grp78 promoter by malfolded proteins, glycosylation block, and calcium inonophore is mediated through a proximal region containing a CCAAT motif which interacts with CTF/NF-I. Mol. Cell Biol. 1991, 11, 5612–5623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allenby, G.; Bosque, M.T.; Saunders, M.; Kramer, S.; Speck, J. Retinoic acid receptors and retinoic X receptors: Interactions with endogenous retinoic acids. Proc. Nation. Acad. Sci. 1993, 90, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammer, E.J.; Chen, D.T.; Hoar, R.M.; Agnish, N.D.; Benke, P.J.; Braun, J.T.; Curry, C.J.; Fernhoff, P.M.; Grix, A.M.; Lott, I.T. Retinoid acid and embryo- pathology. New Engl. J. Med. 1985, 313, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2002 by MDPI (http://www.mdpi.org).

Share and Cite

Dorsey, W.C.; Tchounwou, P.B.; Ishaque, A.B.; Shen, E. Transcriptional Activation of Stress Genes and Cytotoxicity in Human Liver Carcinoma (HepG2) Cells Exposed to Pentachlorophenol. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2002, 3, 992-1007. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/i3090992

Dorsey WC, Tchounwou PB, Ishaque AB, Shen E. Transcriptional Activation of Stress Genes and Cytotoxicity in Human Liver Carcinoma (HepG2) Cells Exposed to Pentachlorophenol. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2002; 3(9):992-1007. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/i3090992

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorsey, Waneene C., Paul B. Tchounwou, Ali B. Ishaque, and Elaine Shen. 2002. "Transcriptional Activation of Stress Genes and Cytotoxicity in Human Liver Carcinoma (HepG2) Cells Exposed to Pentachlorophenol" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 3, no. 9: 992-1007. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/i3090992