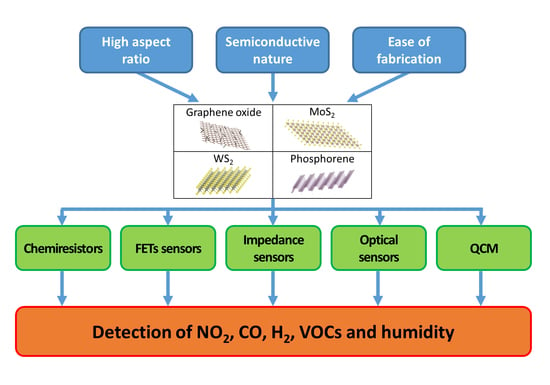

2D Materials for Gas Sensing Applications: A Review on Graphene Oxide, MoS2, WS2 and Phosphorene

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Gas Sensing Devices

2.1. Sensing Performance Parameters

2.2. Chemiresistors

2.3. Field Effect Transistors (FETs)

2.4. Impedance Sensors

2.5. Optical Gas Sensors

2.6. Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) Gas Sensors

3. Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide Sensors

4. MoS2 Gas Sensors

5. WS2 Gas Sensors

6. Phosphorene Gas Sensors

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janata, J.; Josowicz, M. Conducting polymers in electronic chemical sensors. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miasik, J.J.; Hooper, A.; Tofield, B.C. Conducting polymer gas sensors. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1 1986, 82, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virji, S.; Huang, J.; Kaner, R.B.; Weiller, B.H. Polyaniline Nanofiber Gas Sensors: Examination of Response Mechanisms. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Ye, Q.; Cinke, M.; Han, J.; Meyyappan, M. Carbon Nanotube Sensors for Gas and Organic Vapor Detection. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yeow, J.T.W. A Review on Carbon Nanotubes-Based Gas Sensors. J. Sens. 2009, 2009, 493904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanan, S.M.; El-Kadri, O.M. Semiconducting Metal Oxide Based Sensors for Selective Gas Pollutant Detection. Sensors 2009, 9, 8158–8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, Y.-F.; Liu, S.-B.; Meng, F.-L.; Liu, J.-Y.; Jin, Z.; Kong, L.-T.; Liu, J.-H. Metal Oxide Nanostructures and Their Gas Sensing Properties: A Review. Sensors 2012, 12, 2610–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fine, G.F.; Cavanagh, L.M.; Afonja, A.; Binions, R. Metal Oxide Semi-Conductor Gas Sensors in Environmental Monitoring. Sensors 2010, 10, 5469–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ponzoni, A.; Baratto, C.; Cattabiani, N.; Falasconi, M.; Galstyan, V.; Nunez-Carmona, E.; Rigoni, F.; Sberveglieri, V.; Zambotti, G.; Zappa, D. Metal Oxide Gas Sensors, a Survey of Selectivity Issues Addressed at the SENSOR Lab, Brescia (Italy). Sensors 2017, 17, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yin, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, D.; Gao, R. Metal Oxide Gas Sensors: Sensitivity and Influencing Factors. Sensors 2010, 10, 2088–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bai, H.; Shi, G. Gas Sensors Based on conducting Polymers. Sensors 2007, 7, 267–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H. Current Trends in Sensors Based on Conducting Polymer Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2013, 3, 524–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheah, R.; Forsyth, M.; Truong, V.-T. Ordering and stability in conducting polypyrrole. Synth. Met. 1998, 94, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, P.R. The Band Theory of Graphite. Phys. Rev. 1947, 71, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weiss, N.O.; Zhou, H.; Liao, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. Graphene: An Emerging Electronic Material. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 5782–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abergel, D.S.L.; Apalkov, V.; Berashevich, J.; Ziegler, K.; Chakraborty, T. Properties of graphene: A theoretical perspective. Adv. Phys. 2010, 59, 261–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, Z.; Xie, D.; Fang, Y. Graphene. Fabrication, Characterizations, Properties and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MS, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-M.; Avouris, P. Strong Suppression of Electrical Noise in Bilayer Graphene Nanodevices. Nanoletters 2008, 8, 2119–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mak, K.F.; Lee, C.; Hone, J.; Shan, J.; Heinz, T.F. Atomically Thin MoS2: A new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Neal, A.T.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, Z.; Xu, X.; Tomanek, D.; Ye, P.D. Phosphorene: An unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 4033–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.; Choudhary, N.; Han, G.H.; Park, J.; Akinwande, D.; Lee, Y.H. Recent development of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides and their applications. Mater. Today 2017, 20, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappa, D. Molybdenum Dichalcogenides for Environmental Chemical Sensing. Materials 2017, 10, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Phan, D.-T.; Ahn, S.; Nam, K.-H.; Park, C.-M.; Jeon, K.-J. Two-dimensional SnS2 materials as high-performance NO2 sensors with fast response and high sensitivity. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2018, 255, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannix, A.J.; Kiraly, B.; Hersam, M.C.; Guisinger, N.P. Synthesis and chemistry of elemental 2D materials. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, L.; Chen, C.; Smith, S.C. Phosphorene: Fabrication, Properties, and Applications. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 2794–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Molle, A.; Grazianetti, C.; Tao, L.; Taneja, D.; Alam, M.H.; Akinwande, D. Silicene, silicene derivatives, and their device applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 6370–6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, P.; De Padova, P.; Quaresima, C.; Avila, J.; Frantzeskakis, E.; Asensio, M.C.; Resta, A.; Ealet, B.; Le Lay, G. Silicene: Compelling Experimental Evidence for Graphenelike Two-Dimensional Silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 155501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, M.E.; Xian, L.; Cahangirov, S.; Rubio, A.; Le Lay, G. Germanene: A novel two-dimensional germanium allotrope akin to graphene and silicene. New J. Phys. 2014, 16, 095002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, T.; Pinna, N.; Zhang, J. Two-Dimensional Nanostructured Materials for Gas Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1702168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Hayasaka, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Oliveira, O.N., Jr.; Lin, L. A review on chemiresistive room temperature gas sensors based on metal oxidenanostructures, graphene and 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Jiang, C.; Wei, S. Gas sensing in 2D materials. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2017, 4, 021304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, S.S.; Varghese, S.H.; Swaminathan, S.; Singh, K.K.; Mittal, V. Two-Dimensional Materials for Sensing: Graphene and Beyond. Electronics 2015, 4, 651–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barsan, N.; Weimar, U. Conduction Model of Metal Oxide Gas Sensors. J. Electroceram. 2001, 7, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Cadena, G.; Riu, J.; Rius, F.X. Gas sensors based on nanostructured materials. Analyst 2007, 132, 1083–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leenaerts, O.; Partoens, B.; Peeters, F.M. Adsorption of H2O, NH3, CO, NO2, and NO on graphene: A first –principles study. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 125416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Primary National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS); United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Donarelli, M.; Milan, R.; Rigoni, F.; Drera, G.; Sangaletti, L.; Ponzoni, A.; Baratto, C.; Sberveglieri, G.; Comini, E. Anomalous gas sensing behaviors to reducing agents of hydrothermally grown α-Fe2O3 nanorods. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2018, 273, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurlo, A.; Bârsan, N.; Oprea, A.; Sahm, M.; Sahm, T.; Weimar, U. An n- to p-type conductivity transition induced by oxygen adsorption on α-Fe2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 2280–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.M.; Dinan, B.; Akbar, S.A.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A. Gas Sensors Based on One Dimensional Nanostructured Metal-Oxides: A Review. Sensors 2012, 12, 7207–7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Korotcenkov, G.; Cho, B.K. Instability of metal oxide-based conductometric gas sensors and approaches to stability improvement (short survey). Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2011, 156, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Yao, Y.; Quan, W.; Liu, B. Enhanced sensitivity of ammonia sensor using graphene/polyaniline nanocomposite. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2013, 178, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Park, S.; Yu, K.; Ruoff, R.S.; Ocola, L.E.; Rosenmann, D. Toward Practical Gas Sensing with Highly Reduced Graphene Oxide: A New Signal Processing Method to Circumvent Run-to-Run and Device-to-Device Variations. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barochi, G.; Rossignol, J.; Bouvet, M. Development of microwave gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2011, 157, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorga-Martinez, C.C.; Ambrosi, A.; Eng, A.Y.S.; Sofer, Z.; Pumera, M. Metallic 1T-WS2 for Selective Impedimetric Vapor Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 5611–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cittadini, M.; Bersani, M.; Perrozzi, F.; Ottaviano, L.; Wlodarski, W.; Martucci, A. Graphene oxide coupled with gold nanoparticles for localized surface plasmon resonance based gas sensor. Carbon 2014, 69, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Baillargeat, D.; Ho, H.-P.; Yong, K.-T. Nanomaterials enhanced surface plasmon resonance for biological and chemical sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 3426–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piliarik, M.; Homola, J. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensors: Approaching their limits? Opt. Express 2009, 17, 16505–16517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Song, D. A Novel Graphene Oxide-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for Immunoassey. Small 2013, 9, 2537–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Hu, S.; Xia, J.; Anderson, T.; Dinh, X.-Q.; Meng, X.-M.; Coquet, P.; Yong, K.-T. Graphene-MoS2 hybrid nanostructures enhanced surface plasmon resonances biosensors. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2015, 207, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerbrey, G. Verwendung von Schwingquarzen zur Wägung dünner Schichten und zur Microwägung. Z. Phys. 1959, 155, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashist, S.K.; Vashist, P. Recent Advances in Quartz Crystal Microbalance-Based Sensors. J. Sens. 2011, 2011, 571405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, V.V.; Hung, V.N.; Tuan, L.A.; Phan, V.N.; Huy, T.Q.; Quy, N.V. Graphene-coated quartz crystal microbalance for detection of volatile organic compounds at room temperature. Thin Solid Films 2014, 568, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekaew, Y.; Lokavee, S.; Phokharatkul, D.; Wisitsoraat, A.; Kerdcharoen, T.; Wongchoosuk, C. Low-cost and flexible printed graphene-PEDOT:PSS gas sensor for ammonia detection. Org. Electron. 2014, 15, 2971–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Lee, S.; Seo, J.; Pyo, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, T. A Highly Sensitive Hydrogen Sensor with Gas Selectivity Using a PMMA Membrane-Coated Pd Nanoparticle/Single-Layer Graphene Hybrid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 18, 3554–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.G.; Kim, D.-H.; Seo, D.K.; Kim, T.; Im, H.U.; Lee, H.M.; Yoo, J.-B.; Hong, S.-H.; Kang, T.J.; Kim, Y.H. Flexible hydrogen sensors using graphene with palladium nanoparticle decoration. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2012, 169, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liu, Z.; Jauregui, L.A.; Yu, Q.; Pillai, R.; Cao, H.; Bao, J.; Chen, Y.P.; Pei, S.-S. Wafer-scale synthesis of graphene by chemical vapor deposition and its application in hydrogen sensing. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2010, 150, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, K.; Xie, H. High sensitive formaldehyde graphene gas sensor modified by atomic layer deposition zinc oxide films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 033107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Lee, J.M.; Park, W.I. Vertically aligned ZnO nanorods and graphene hybrid architectures for high-sensitive flexible gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2011, 155, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tian, C.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Shi, K.; Zhou, W.; Fu, H. Facile synthesis of novel 3D nanoflower-like CuxO/multilayer graphene composites for room temperature NOx gas sensor application. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, R.; Song, G.; Yu, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J. Highly aligned SnO2 nanorods on graphene sheets for gas sensors. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 17360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummers, W.S.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniela, C.; Marcano, V.D.; Kosynkin, J.M.; Berlin, J.M.; Sinitskii, A.; Sun, Z.; Slesarev, A. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4806–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Hu, Y.; Shi, M.; Lu, X.; Qin, C.; Li, C.; Ye, M. Fast and facile preparation of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide nanoplatelets. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 3514–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liang, J.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Size-controlled synthesis of graphene oxide sheets on a large scale using chemical exfoliation. Carbon 2009, 47, 3365–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Hu, Y.; Hwang, J.O.; Lee, E.S.; Casabianca, L.B.; Cai, W.; Potts, J.R.; Ha, H.W.; Chen, S.; Oh, J.; et al. Chemical structures of hydrazine-treated graphene oxide and generation of aromatic nitrogen doping. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stankovich, S.; Dikin, D.A.; Piner, R.D.; Kohlhaas, K.A.; Kleinhammes, A.; Jia, Y.; Wu, Y.; Nguyen, S.T.; Ruoff, R.S. Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. Carbon 2007, 45, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treossi, E.; Melucci, M.; Liscio, A.; Gazzano, M.; Samorì, P.; Palermo, V. High-Contrast Visualization of Graphene Oxide on Dye-Sensitized Glass, Quartz, and Silicon by Fluorescence Quenching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15576–15577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borini, S.; White, R.; Wei, D.; Astley, M.; Haque, S.; Spigone, E.; Harris, N.; Kivioja, J.; Ryhänen, T. Ultrafast Graphene Oxide Humidity Sensors. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 11166–11173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Leng, T.; Georgiou, T.; Abraham, J.; Nair, R.R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Hu, Z. Graphene Oxide Dielectric Permittivity at GHz and Its Applications for Wireless Humidity Sensing. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, H.; Yin, K.; Xie, X.; Ji, J.; Wan, S.; Sun, L.; Terrones, M.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Ultrahigh humidity sensitivity of graphene oxide. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Kang, X.; Zuo, Q.; Yuan, C.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Lu, H.; Chen, J. Fabrication and Evaluation of a Graphene Oxide-Based Capacitive Humidity Sensor. Sensors 2016, 16, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Chen, X.-D.; Chen, X.-P.; Ding, X.; Li, X.-Y. Subsecond Response of Humidity Sensor Based on Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots. IEEE Electr. Device Lett. 2015, 36, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.-L.; Hou, Z.-L.; Zhang, B.-X.; Zhao, Q.-L. Highly sensitive humidity sensor based on graphene oxide foam. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 153101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Chen, W.; Yan, L. Free-standing dried foam films of graphene oxide for humidity sensing. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2015, 215, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Guo, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, X. Humidity sensing behaviors of graphene oxide-silicon bi-layer flexible structure. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2012, 161, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Guo, H.; Wu, Z. Graphene oxide thin film coated quartz crystal microbalance for humidity detection. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 7778–7782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Li, N. Investigation of the stability of QCM humidity sensor using graphene oxide as sensing films. Sens. Actuator. B-Chem. 2014, 191, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-D.; Wu, C.-W.; Chiang, C.-C. Tilted Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor with Graphene Oxide Coating for Humidity Sensing. Sensors 2017, 17, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prezioso, S.; Perrozzi, F.; Giancaterini, L.; Cantalini, C.; Treossi, E.; Palermo, V.; Nardone, M.; Santucci, S.; Ottaviano, L. Graphene Oxide as a Practical Solution to High Sensitivity Gas Sensing. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 10683–10690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donarelli, M.; Prezioso, S.; Perrozzi, F.; Giancaterini, L.; Cantalini, C.; Treossi, E.; Palermo, V.; Santucci, S.; Ottaviano, L. Graphene oxide for gas detection under standard humidity conditions. 2D Mater. 2015, 2, 035018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Yoon, Y.-G.; Choi, K.S.; Kang, J.H.; Shim, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.H.; Chang, H.J.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, C.R.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. Role of oxygen functional groups in graphene oxide for reversible room-temperature NO2 sensing. Carbon 2015, 91, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Singh, B.; Park, J.-H.; Rathi, S.; Lee, I.; Maeng, S.; Joh, H.-I.; Lee, C.-H.; Kim, G.-H. Dielectrophoresis of graphene oxide nanostructures for hydrogen gas sensor at room temperature. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 194, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Narváez, E.; Merkoçi, A. Graphene Oxide as an Optical Biosensing Platform. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 3298–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavanova, K.; Bakakina, Y.; Burkova, I.; Shtepliuk, I.; Viter, R.; Ubelis, A.; Beni, V.; Starodub, N.; Yakimova, R.; Khranovskyy, V. Application of 2D Non-Graphene Materials and 2D Oxide Nanostructures for Biosensing Technology. Sensors 2016, 16, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Some, S.; Xu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, Y.; Qin, H.; Kulkarni, A.; Kim, T.; Lee, H. Highly Sensitive and Selective Gas Sensor Using Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Graphenes. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Wang, D.; Liu, R.; Pei, X.; Zhang, T.; Jin, J. Edge-tailored graphene oxide nanosheet-based field effect transistors for fast and reversible electronic detection of sulfur dioxide. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolmakov, A.; Klenov, D.O.; Lilach, Y.; Stemmer, S.; Moskovitst, M. Enhanced gas sensing by individual SnO2 nanowires and nanobelts functionalized with Pd catalyst particles. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Choi, S.-J.; Lee, I.; Youn, D.-Y.; Park, C.O.; Lee, J.-H.; Tuller, H.L.; Kim, I.D. Thin-wall assembled SnO2 fibers functionalized by catalytic Pt nanoparticles and their superior exhaled-breath-sensing properties for the diagnosis of diabetes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 2357–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, M.; Ju, D.; Xu, H.; Cao, B. High-performance gas sensor based on ZnO nanowires functionalized by Au nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 199, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, W. Decoration of ZnO nanowires with Pt nanoparticles and their improved gas sensing and photocatalytic performance. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 285501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, M.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, W. A Au-functionalized ZnO nanowire gas sensor for detection of benzene and toluene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 17179–17186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattabiani, N.; Baratto, C.; Zappa, D.; Comini, E.; Donarelli, M.; Ferroni, M.; Ponzoni, A.; Faglia, G. Tin Oxide Nanowires Decorated with Ag Nanoparticles for Visible Light-Enhanced Hydrogen Sensing at Room Temperature: Bridging Conductometric Gas Sensing and Plasmon-Driven Catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 5026–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Park, J.S.; Choi, Y.-R.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Sohn, W.; Shim, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, C.R.; Choi, Y.S.; et al. Chemically fluorinated graphene oxide for room temperature ammonia detection at ppb levels. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 19116–19125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teradal, N.L.; Marx, S.; Morag, A.; Jelineka, R. Porous graphene oxide chemi-capacitor vapor sensor array. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; He, J. Sensing Properties of GO and Amine-Silica Nanoparticles Functionalized QCM Sensors for Detection of Formaldehyde. Int. J. Nanosci. 2014, 13, 1460011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovich, S.; Piner, R.D.; Chen, X.; Wu, N.; Nguyen, S.T.; Ruoff, R.S. Stable aqueous dispersions of graphitic nanoplatelets via the reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide in the presence of poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate). J. Mater. Chem. 2006, 16, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Gong, K. Synthesis of polyaniline-intercalated graphite oxide by an in situ oxidative polymerization reaction. Carbon 1999, 37, 706–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlinos, A.B.; Gournis, D.; Petridis, D.; Szabó, T.; Szeri, A.; Dékány, I. Graphite Oxide: Chemical Reduction to Graphite and Surface Modification with Primary Aliphatic Amines and Amino Acids. Langmuir 2003, 19, 6050–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilje, S.; Han, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.L.; Kaner, R.B. A Chemical Route to Graphene for Device Applications. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 3394–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Navarro, C.; Weitz, R.T.; Bittner, A.M.; Scolari, M.; Mews, A.; Burghard, M.; Kern, K. Electronic Transport Properties of Individual Chemically Reduced Graphene Oxide Sheets. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 3499–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattevi, C.; Eda, G.; Agnoli, S.; Miller, S.; Mkhoyan, K.A.; Mastrogiovanni, D.; Granozzi, G.; Garfunkel, E.; Chhowalla, M. Evolution of Electrical, Chemical, and Structural Properties of Transparent and Conducting Chemically Derived Graphene Thin Films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 2577–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrozzi, F.; Prezioso, S.; Donarelli, M.; Bisti, F.; De Marco, P.; Santucci, S.; Nardone, M.; Treossi, E.; Palermo, V.; Ottaviano, L. Use of Optical Contrast to Estimate the Degree of Reduction of Graphene Oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrozzi, F.; Croce, S.; Treossi, E.; Palermo, V.; Santucci, S.; Fioravanti, G.; Ottaviano, L. Reduction dependent wetting properties of graphene oxide. Carbon 2014, 77, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilje, S.; Dubin, S.; Badakhshan, A.; Farrar, J.; Danczyk, S.A.; Kaner, R.B. Photothermal Deoxygenation of Graphene Oxide for Patterning and Distributed Ignition Applications. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Koinuma, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Taniguchi, T.; Hatakeyama, K.; Tateishi, H.; Ida, S. Simple Photoreduction of Graphene Oxide Nanosheet under Mild Conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 3461–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cote, L.J.; Cruz-Silva, R.; Huang, J. Flash Reduction and Patterning of Graphite Oxide and Its Polymer Composite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11027–11032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Y.; Bao, Q.; Varghese, B.; Ling Tang, L.A.; Tan, C.K.; Sow, C.; Loh, K.P. Microstructuring of Graphene Oxide Nanosheets Using Direct Laser Writing. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, L.; Wei, S.; He, Y.; Xia, H.; Chen, Q.; Sun, H.-B.; Xiao, F.-S. Direct imprinting of microcircuits on graphene oxides film by femtosecond laser reduction. Nano Today 2010, 5, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezioso, S.; Perrozzi, F.; Donarelli, M.; Bisti, F.; Santucci, S.; Palladino, L.; Nardone, M.; Treossi, E.; Palermo, V.; Ottaviano, L. Large area extreme-UV lithography of graphene oxide via spatially resolved photoreduction. Langmuir 2012, 28, 5489–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prezioso, S.; Perrozzi, F.; Donarelli, M.; Stagnini, E.; Treossi, E.; Palermo, V.; Santucci, S.; Nardone, M.; Moras, P.; Ottaviano, L. Dose and wavelength dependent study of graphene oxide photoreduction with VUV Synchrotron radiation. Carbon 2014, 79, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.T.; Perkins, F.K.; Snow, E.S.; Wei, Z.; Sheenan, P.E. Reduced Graphene Oxide Molecular Sensors. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 3137–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shen, S. Ammonia gas sensors based on chemically reduced graphene oxide sheets self-assembled on Au electrodes. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ghosh, R.; Midya, A.; Santra, S.; Ray, S.K.; Guha, P.K. Chemically Reduced Graphene Oxide for Ammonia Detection at Room Temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 7599–7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Ocola, L.E.; Chen, J. Reduced graphene oxide for room-temperature gas sensors. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 445502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.H.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, J.J.; Zeng, L.L.; Tao, X.M.; Chen, W. Holey reduced graphene oxide nanosheets for high performance room temperature gas sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 17415–17420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, V.; Surwade, S.P.; Ammu, S.; Agnihotra, S.R.; Jain, S.; Roberts, K.E.; Park, S.; Ruoff, R.S.; Manohar, S.K. All-Organic Vapor Sensor Using Inkjet-Printed Reduced Graphene Oxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 2154–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duy, L.T.; Trung, T.Q.; Hanif, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Roh, E.; Lee, W.; Lee, N.-E. A stretchable and highly sensitive chemical sensor using multilayered network of polyurethane nanofibres with self-assembled reduced graphene oxide. 2D Mater. 2017, 4, 025062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-J.; Kim, S.-J.; Jang, J.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, L.-D. Silver Nanowire Embedded Colorless Polyimide Heater for Wearable Chemical Sensors: Improved Reversible Reaction Kinetics of Optically Reduced Graphene Oxide. Small 2016, 12, 5826–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Liu, R.; Peng, X.; Chen, Q.; Wu, J. 2D Hybrid Nanomaterials for Selective Detection of NO2 and SO2 Using “Light On and Off” Strategy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 37191–37200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zou, C.; Su, Y.; Li, M.; Hu, N.; Ni, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced NO2 sensing performance of reduced graphene oxide by in situ anchoring carbon dots. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 6862–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridevi, S.; Vasub, K.S.; Bhat, N.; Asokan, S.; Sood, A.K. Ultra sensitive NO2 gas detection using the reduced graphene oxide coated etched fiber Bragg gratings. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2016, 223, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, S.M.; Ritikos, R.; Whitcher, T.J.; Razib, N.M.; Bien, D.C.S.; Chanlek, N.; Nakajima, H.; Saiposa, T.; Songsiriritthigul, P.; Huang, N.M.; et al. A practical carbon dioxide gas sensor using room-temperature hydrogen plasma reduced graphene oxide. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 193, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Geng, X.; Guo, Y.; Rong, J.; Gong, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Xu, J.; Cheng, G.; et al. Reduced Graphene Oxide Electrically Contacted Graphene Sensor for Highly Sensitive Nitric Oxide Detection. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6955–6961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Wang, Y.; Chai, J.; Gao, R.; Yang, Z.; Kong, E.S.-W.; Zhang, Y. Gas sensor based on p-phenylenediamine reduced graphene oxide. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2012, 163, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedala, H.; Sorescu, D.C.; Kotchey, G.P.; Star, A. Chemical Sensitivity of Graphene Edges Decorated with Metal Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 2342–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, D.-T.; Chung, G.-S. A novel Pd nanocube-graphene hybrid for hydrogen detection. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 199, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, D.-T.; Chung, G.-S. Characteristics of resistivity-type hydrogen sensing based on palladium-graphene nanocomposites. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, D.-T.; Chung, G.-S. Effects of Pd nanocube size of Pd nanocube-graphene hybrid on hydrogen sensing properties. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 204, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Mao, S.; Wen, Z.; Chang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. Controllable synthesis of silver nanoparticle-decorated reduced graphene oxide hybrids for ammonia detection. Analyst 2013, 138, 2877–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Pu, J.; Lin, Y.; Xu, S.; Shen, L.; Chen, Q.; Shi, W. Fully Printed, Rapid-Response Sensors Based on Chemically Modified Graphene for Detecting NO2 at Room Temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 7426–7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galstyan, V.; Comini, E.; Kholmanov, I.; Faglia, G.; Sberveglieri, G. Reduced graphene oxide/ZnO nanocomposite for application in chemical gas sensors. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 34225–34232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, B.; Zhang, H.; Fei, T.; Zhang, T. Enhancing NO2 gas sensing performances at room temperature based on reduced graphene oxide-ZnO nanoparticles hybrids. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 202, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wan, P.; Zhou, X.; Hu, J.; Guan, Y.; Feng, L. Additive-Free Synthesis of In2O3 Cubes Embedded into Graphene Sheets and Their Enhanced NO2 Sensing Performances at Room Temperature. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 21093–21100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.; Nie, R.; Han, D.; Wang, Z. In2O3-graphene nanocomposite based gas sensor for selective detection of NO2 at room temperature. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2015, 219, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.-G.; Peng, S.-L. Fabrication and NO2 gas-sensing properties of reduced graphene oxide/WO3 nanocomposite films. Talanta 2015, 132, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Tjoa, V.; Fan, H.M.; Tan, H.R.; Sayle, D.C.; Olivo, M.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Wei, J.; Sow, C.H. Reduced Graphene Oxide Conjugated Cu2O Nanowire Mesocrystals for High-Perfomance NO2 Gas Sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4905–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.-L.; Li, X.; Xie, D.; Xiang, L.; Komarneni, S. Confined Formation of Ultrathin ZnO Nanorods/Reduced Graphene Oxide Mesoporous Nanocomposites for High-Performance Room-Temperature NO2 Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 35454–35463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zeng, D.; Zhao, S.; Wu, J.; Xu, K.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Xie, C. Room temperature NO2 sensing: What advantage does the rGO-NiO composite have over pristine NiO? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 14903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, J.; Fei, T.; Liu, S.; Zhang, T. SnO2 nanoparticles-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for NO2 sensing at low operating temperature. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 190, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Upadhyay, S.B.; Kushwaha, A.; Kim, T.-H.; Murali, G.; Verma, R.; Srivastava, M.; Singh, J.; Sahay, P.P.; Lee, S.H. SnO2 quantum dots decorated on RGO: A superior sensitive, selective and reproducible performance for a H2 and LPG sensor. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 11971–11979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esfandiar, A.; Irajizad, A.; Akhavan, O.; Ghasemi, S.; Gholami, M.R. Pd-WO3/reduced graphene oxide hierarchical nanostructures as efficient hydrogen gas sensors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 8169–8179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Sun, F.; Pan, Z.; Huang, C.; Yang, S.; Long, J.; Chen, Y. Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Ordered Macroporous Films on a Curved Surface: General Fabrication and Application in Gas Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 3428–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Zhu, J.; Wang, C.; Yu, S.; Bi, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Fabrication of α-Fe2O3@graphene nanostructures for enhanced gas-sensing property to ethanol. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 292, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wei, Z.; Wang, B.; Luo, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Yu, H.; Li, M.; Huang, Z.; Zang, J.; et al. Sensitive Room-Temperature H2S Gas Sensors Employing SnO2 Quantum Wire/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, D.; Bhattacharyya, P. Highly Efficient Room-Temperature Gas Sensor Based on TiO2 Nanotube-Reduced Graphene-Oxide Hybrid Device. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2016, 37, 656–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jiang, C.; Liu, J.; Cao, Y. Carbon monoxide gas sensing at room temperature using copper oxide-decorated graphene hybrid nanocomposite prepared by layer-by-layer self-assembly. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 247, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Jiang, C.; Liu, A.; Xia, B. Quantitative detection of formaldehyde and ammonia gas via metal oxide-modified graphene-based sensor array combining with neural network model. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 240, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, H. Two-dimensional MoS2: Properties, preparation, and applications. J. Mater. 2015, 1, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kis, A.; Coleman, J.N.; Strano, M.S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wan, J.; Lacey, S.D.; Dai, J.; Bao, W.; Fuhrer, M.S.; Hu, L. Tuning two-dimensional nanomaterials by intercalation: Materials, properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 6742–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, J.N.; Lotya, M.; O’Neill, A.; Bergin, S.D.; King, P.J.; Khan, U.; Young, K.; Gaucher, A.; De, S.; Smith, R.J.; et al. Two-Dimensional Nanosheets Produced by Liquid Exfoliation of Layered Materials. Science 2011, 331, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, K.; Mao, N.; Wang, H.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, H. A Mixed-Solvent Strategy for Efficient Exfoliation of Inorganic Graphene Analogues. Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 11031–11034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yap, C.C.R.; Tay, B.K.; Edwin, T.H.T.; Olivier, A.; Baillargeat, D. From Bulk to Monolayer MoS2: Evolution of Raman Scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, L.; Palleschi, S.; Perrozzi, F.; D’Olimpio, G.; Priante, F.; Donarelli, M.; Nardone, M.; Benassi, P.; Gonchigsuren, M.; Gombosuren, M.; et al. Mechanical exfoliation and layer number identification of MoS2 revisited. 2D Mater. 2017, 4, 045013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splendiani, A.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Kim, J.; Chim, C.-Y.; Galli, G.; Wang, F. Emerging Photoluminescence in Monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Jiang, D.; Schedin, F.; Booth, T.J.; Khotkevich, V.V.; Morozov, S.V.; Geim, A.K. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10451–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Radisavljevic, B.; Radenovic, A.; Brivio, J.; Giacometti, V.; Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Xue, J.; Kang, W. Gas adsorption on MoS2 monolayer from first-principles calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 595–596, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Salami, N. Gas sensor based on MoS2 monolayer. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2016, 236, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.; Kim, A.R.; Park, Y.; Yoon, J.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, S.; Yoo, T.J.; Kang, C.G.; Lee, B.H.; Ko, H.C.; et al. Bifunctional Sensing Characteristic of Chemical Vapor Deposition Synthesized Atomic-Layered MoS2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 2952–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Chen, L.; Liu, G.; Abbas, A.N.; Fathi, M.; Zhou, C. High-Performance Chemical Sensing Usng Shottky-Contacted Chemical Vapor Deposition Grown Monolayer MoS2 Transistors. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5304–5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yin, Z.; He, Q.; Li, H.; Huang, X.; Lu, G.; Fam, D.W.H.; Tok, A.I.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H. Fabrication of Single- and Multilayer MoS2 Film-Based Field-Effect Transistors for Sensing NO at Room Temperature. Small 2012, 8, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donarelli, M.; Prezioso, S.; Perrozzi, F.; Bisti, F.; Nardone, M.; Giancaterini, L.; Cantalini, C.; Ottaviano, L. Response to NO2 and other gases of resistive chemically exfoliated MoS2-based gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2015, 207, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-L.; Choi, H.-H.; Yue, H.-Y.; Yang, W.-C. Controlled exfoliation of molybdenum disulfide for developing thin film humidity sensor. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2014, 14, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Late, D.J.; Huang, Y.-K.; Liu, B.; Acharya, J.; Shirodkar, S.N.; Luo, J.; Yan, A.; Charles, D.; Waghmare, U.V.; Dravid, V.P.; et al. Sensing Behavior of Atomically Thin-Layered MoS2 Transistors. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 4879–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, F.K.; Friedman, A.L.; Cobas, E.; Campbell, P.M.; Jernigan, G.G.; Jonker, B.T. Chemical Vapor Sensing with Monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Zeng, Z.; Yin, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Huang, X.; Zhang, H. Fabrication of Flexible MoS2 Thin-Film Transistor Arrays for Practical Gas-Sensing Applications. Small 2012, 8, 2994–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.J.; Hao, L.Z.; Gao, W.; Liu, Y.M.; Li, G.X.; Xue, Q.Z.; Guo, W.Y.; Yu, L.Q.; Wu, Z.P.; Liu, X.H.; et al. Growth and humidity-dependent electrical properties of bulk-like MoS2 thin films on Si. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 74329–74335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Gatensby, R.; McEvoy, N.; Hallam, T.; Duesberg, G.S. High-Performance Sensors Based on Molybdenum Disulfide Thin Films. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6699–6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koh, E.W.K.; Chiu, C.H.; Lim, Y.K.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Pan, H. Hydrogen adsorption on and diffusion through MoS2 monolayer: First-principles studies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 14323–14328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Sun, X.; Hou, T.; Li, Y. Molibdenum disulfide as a highly efficient adsorbent for non-polar gases. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 11700–11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.-Y.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.-S.; Jung, W.-B.; Yoo, H.-W.; Kim, J.; Jung, H.-T. Highly Enhanced Gas Adsorption Properties in Vertically Aligned MoS2 Layers. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9314–9321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Song, P.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q. Dispersed SnO2 nanoparticles on MoS2 nanosheets for superior gas-sensing performances to ethanol. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 79593–79599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Wen, Z.; Huang, X.; Chang, J.; Chen, J. Stabilizing MoS2 Nanosheets through SnO2 Nanocrystal Decoration for High-Performance Gas Sensing in Air. Small 2015, 11, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Song, P.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q. Facile synthesis, characterization and gas sensing performance of ZnO nanoparticles-coated MoS2 nanosheets. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 662, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Song, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q. A low temperature gas sensor based on Au-loaded MoS2 hierarchical nanostructures for detecting ammonia. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 9327–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-Y.; Koh, H.-J.; Yoo, H.-W.; Kim, J.-S.; Jung, H.-T. Tunable Volatile-Organic-Compound Sensor by Using Au Nanoparticle Incorporation on MoS2. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, D.; Xie, X.; Kang, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Navarrete, J.; Moskovits, M.; Banerjee, K. Functionalization of Transition Metal Dichalcogenides with Metallic Nanoparticles: Implications for Doping and Gas-Sensing. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 2852–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, B.; Yoon, J.; Lim, S.K.; Kim, A.R.; Choi, S.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, B.H.; Ko, H.C.; Hahm, M.G. Metal Decoration Effects on the Gas-Sensing Properties of 2D Hybrid-Structures on Flexible Substrates. Sensors 2015, 15, 24903–24913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baek, D.-H.; Kim, J. MoS2 gas sensor functionalized by Pd for the detection of hydrogen. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 250, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, C.; Choi, C.; Kargar, A.; Choi, D.; Kim, Y.J.; Liu, C.H.; Yavuz, S.; Jin, S. MoS2 Nanosheet-Pd Nanoparticle Composite for Highly Sensitive Room Temperature Detection of Hydrogen. Adv. Sci. 2015, 2, 1500004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, B.; Yoon, J.; Lim, S.K.; Kim, A.R.; Kim, D.-H.; Park, S.-G.; Kwon, J.-D.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, K.-H.; Lee, B.H.; et al. Chemical Sensing of 2D Graphene/MoS2 Heterostructure device. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 16775–16780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhu, X.; Guo, Y. Ultrasensitive NO2 gas sensing based on rGO/MoS2 nanocomposite film at low temperature. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 251, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Wang, R.; Jiao, W.; Ding, G.; Hao, L.; Yang, F.; He, X. MoS2 graphene fiber based gas sensing devices. Carbon 2015, 95, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Rumyantsev, S.L.; Jiang, C.; Shur, M.S.; Balandin, A.A. Selective Gas Sensing With h-BN Capped MoS2 Heterostructure Thin-Film Transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2015, 36, 1202–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, M.; Moradinasab, M.; Fathipour, M. The transport and optical sensing properties of MoS2, MoSe2, WS2 and WSe2 semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2018, 33, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongay, S.; Zhou, J.; Ataca, C.; Liu, J.; Kang, J.S.; Matthews, T.S.; You, L.; Li, J.; Grossman, J.C.; Wu, J. Broad-Range Modulation of Light Emission in Two-Dimensional Semiconductors by Molecular Physisorption Gating. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 2831–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, V.Q.; Pam, T.-T.; Le, D.A.; Thi, C.M.; Le, M.H. A first-principles investigation of various gas (CO, H2O, NO, and O2) absorptions on a WS2 monolayer: Stability and electronic properties. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 305005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.J.; Yang, W.H.; Wu, Y.P.; Lin, W.; Zhu, H.L. Theoretical study of the interaction of electron donor and acceptor molecules with monolayer WS2. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2015, 48, 285303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawbake, A.S.; Waykar, R.G.; Late, D.J.; Jadkar, S.R. Highly Transparent Wafer-Scale Synthesis of Crystalline WS2 Nanoparticle Thin Film for Photodetector and Humidity-Sensing Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 3359–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, M.; Lee, K.; Morrish, R.; Berner, N.C.; McEvoy, N.; Wolden, C.A.; Duesberg, G.S. Plasma assisted synthesis of WS2 for gas sensing applications. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 615, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrozzi, F.; Emamjomeh, S.M.; Paolucci, V.; Taglieri, G.; Ottaviano, L.; Cantalini, C. Thermal stability of WS2 flakes and gas sensing properties of WS2/WO3 composite to H2, NH3 and NO2. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 243, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Harley-Trochimczyk, A.; Long, H.; Chan, L.; Pham, T.; Hu, M.; Qin, Y.; Zettl, A.; Carraro, C.; Worsley, M.A.; et al. Conductometric gas sensing behavior of WS2 aerogel. FlatChem 2017, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.-H.; Choi, S.-J.; Yu, S.; Kim, I.-D. 2D WS2-edge functionalized multi-channel carbon nanofibers: Effect of WS2 edge-abundant structure on room temperature NO2 sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 8725–8732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Worsley, M.A.; Pham, T.; Zettl, A.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R. Effects of ambient humidity and temperature on the NO2 sensing characteristics of WS2/graphene aerogel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 450, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.Y.; Song, J.-G.; Kim, Y.; Choi, T.; Shin, S.; Lee, C.W.; Lee, K.; Koo, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.; et al. Improvement of Gas-Sensing Performance of Large Area Tungsten Disulfide Nanosheets by Surface Functionalization. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 9287–9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuru, C.; Choi, D.; Kargar, A.; Liu, C.H.; Yavuz, S.; Choi, C.; Jin, S.; Bandaru, P.R. High-performance flexible hydrogen sensor made of WS2 nanosheet-Pd nanoparticle composite film. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 195501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, C.; Chen, Y.; Qin, Z.; Zeng, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Xie, C. Two-dimensional WS2-based nanosheets modified by Pt quantum dots for enhanced room temperature NH3 sensing properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 455, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Ouyang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wan, L.; Wang, S.; Xie, C.; Zeng, D. 2D WS2 nanosheets with TiO2 quantum dots decoration for high-performance ammonia gas sensing at room temperature. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 253, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, N.; Yang, S.; Wei, Z.; Li, S.-S.; Xia, J.-B.; Li, J. Photoresponsive and Gas Sensing Field-Effect Transistor based on Multilayer WS2 Nanoflakes. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lu, S.; Wang, Z.; Tang, S.; Shao, J.; Sun, Z.; Xie, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.-F.; et al. From Black Phosphorus to Phosphorene: Basic Solvent Exfoliation, Evolution of Raman Scattering, and Applications to Ultrafast Photonics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 6996–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Gomez, A.; Vicarelli, L.; Prada, E.; Island, J.O.; Narasimha-Acharya, K.L.; Blanter, S.I.; Groenendijk, D.J.; Buscema, M.; Steele, G.A.; Alvarez, J.V. Isolation and characterization of few-layer black phosphorus. 2D Mater. 2014, 1, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abbas, A.N.; Liu, B.; Chen, L.; Ma, Y.; Cong, S.; Aroonyadet, N.; Köpf, M.; Nilges, T.; Zhou, C. Black Phosphorus Gas Sensors. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 5618–5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woomer, A.H.; Farnsworth, T.W.; Hu, J.; Wells, R.A.; Donley, C.L.; Warren, S.C. Phosphorene: Synthesis, Scale-Up, and Quantitative Optical Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 8869–8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Ke, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.-W. Energetics, Charge Transfer, and Magnetism of Small Molecules Physisorbed on Phosphorene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 3102–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kou, L.; Frauenheim, T.; Chen, C. Phosphorene as a Superior Gas Sensor: Selective Adsorption and Distinct I-V Response. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2675–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.-J.; Wang, D.-W.; Wang, X.-H.; Chu, J.-F.; Lv, P.-L.; Liu, Y.; Rong, M.-Z. Phosphorene: A Promising Candidate for Highly Sensitive and Selective SF6 Decomposition Gas Sensors. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 2017, 38, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.D.; Wells, S.A.; Jariwala, D.; Chen, K.-S.; Cho, E.K.; Sangwan, V.K.; Liu, X.; Lauhon, L.J.; Marks, T.J.; Hersam, M.C. Effective Passivation of Exfoliated Black Phosphorus Transistors against Ambient Degradation. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 6964–6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cui, S.; Pu, H.; Wells, S.A.; Wen, Z.; Mao, S.; Chang, J.; Hersam, M.C.; Chen, J. Ultrahigh sensitivity and layer-dependent sensing performance of phosphorene-based gas sensors. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Jung, S.; Jang, S.; Kim, J. Suspended black phosphorus nanosheet gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 250, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donarelli, M.; Ottaviano, L.; Giancaterini, L.; Fioravanti, G.; Perrozzi, F.; Cantalini, C. Exfoliated black phosphorus gas sensing properties at room temperature. 2D Mater. 2016, 3, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.; Koh, H.-J.; Jung, H.; Kim, J.-S.; Yoo, H.W.; Kim, J.; Jung, H.-T. Superior Chemical Sensing Performance of Black Phosphorus: Comparison with MoS2 and Graphene. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 7020–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanlon, D.; Backes, C.; Doherty, E.; Cucinotta, C.S.; Berner, N.C.; Boland, C.; Lee, K.; Harvey, A.; Lynch, P.; Gholamvand, Z.; et al. Liquid exfoliation of solvent-stabilized few-layer black phosphorus for applications beyond electronics. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Sofer, Z.; Pumera, M. Voltammetry of Layered Black Phosphorus: Electrochemistry of Multilayer Phosphorene. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorga-Martinez, C.C.; Sofer, Z.; Pumera, M. Layered Black Phosphorus as a Selective Vapor Sensor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14317–14320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Erande, M.B.; Pawar, M.S.; Late, D.J. Humidity Sensing and Photodetection Behavior of Electrochemically Exfoliated Atomically Thin-Layered Black Phosphorus Nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 11548–11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Late, D.J. Liquid exfoliation of black phosphorus nanosheets and its application as humidity sensor. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 225, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasaei, P.; Behranginia, A.; Foroozan, T.; Asadi, M.; Kim, K.; Khalili-Araghi, F.; Salehi-Khojin, A. Stable and Selective Humidity Sensing Using Stacked Black Phosphorus Flakes. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9898–9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Cai, L.; Zhang, S.; Nah, J.; Yeom, J.; Wang, C. Air-Stable Humidity Sensor Using Few-Layer Black Phosphorus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 10019–10026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Ma, W.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Du, J. Novel QCM humidity sensors using stacked black phosphorus nanosheets as sensing film. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 244, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.Y.; Yu, Z.Y.; Shen, H.Y.; Sun, X.L.; Wan, N.; Yu, H. CO Adsorption on Metal-Decorated Phosphorene. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3957–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Jung, S.; Jang, S.; Kim, J. Platinum-functionalized black phosphorus hydrogen sensors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 242103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-Y.; Koh, H.-J.; Yoo, H.-W.; Jung, H.-T. Tunable Chemical Sensing Performance of Black Phosphorus by Controlled Functionalization with Noble Metals. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7197–7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Device | Target Gas | LOD | OT (°C) | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO | resistive | NO2 | 20 ppb in dry air | 150 | The responses for concentrations >40 ppb are not affected by RH | [81] |

| GO | resistive | NO2 | 650 ppb (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [82] |

| GO | resistive | H2 | 100 ppm | RT | GO shows n-type behaviour. Low response and recovery times | [83] |

| edge-tailored GO | FET | SO2 | 5 ppm | RT | Sensing tests at 65% RH | [87] |

| fluorinated-GO | resistive | NH3 | 6 ppb (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [94] |

| rGO | resistive | NH3 | 5 ppb | RT | Sensing tests at RH < 5% | [113] |

| holey rGO | resistive | NO2 | 60 ppb | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [116] |

| rGO | resistive, flexible | NO2 | 400 ppt | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [117] |

| rGO | resistive, flexible | NO2 | 50 ppb in dry air | RT | Sensing tests in ambient conditions show the ability to detect 1 ppm NO2 | [118] |

| rGO-C nanodots | resistive | NO2 | 10 ppb | RT | Sensing tests in dry air. High selectivity to NO2 | [121] |

| rGO | resistive | CO2 | 300 ppm | RT | Sensing tests in ambient conditions | [123] |

| Pd-RGO | resistive | NO | 2 ppb | RT | Sensing tests in N2 atmosphere | [124] |

| Pt-rGO | FET | H2 | 60 ppm | RT | Sensing tests at 11% ≤ RH ≤ 78%. Selective to H2 over CO and CH4 | [126] |

| Cu2O NWs-rGO | resistive | NO2 | 64 ppb (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in N2 atmosphere | [137] |

| ZnO nanorods-rGO | resistive | NO2 | 47 ppb (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [138] |

| Pd-WO3 nanobelts-rGO | resistive | H2 | 20 ppm | 100 | Sensing tests in dry air. Good selectivity to H2. Recovery time (<1 min) | [142] |

| SnO2 quantum wire-rGO | resistive | H2S | 43 ppb (est.) | RT | Sensing tests at RH = 56–60% | [145] |

| MoS2 | resistive | NO2 | 120 ppb | RT | Sensing tests in N2 atmosphere | [161] |

| MoS2 | FET | NO2 | 20 ppb | RT | Sensing tests in Ar atmosphere | [162] |

| MoS2 | resistive | NH3 | 300 ppb | RT | Sensing tests in N2 atmosphere | [170] |

| Pd-MoS2 | resistive | H2 | 50 ppm | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [181] |

| rGO-MoS2 | resistive | NO2 | 5.7 ppb (est.) in dry air | 60 | Selectivity to NO2 over NH3, H2S, CO and HCHO. Small humidity effects on response | [184] |

| rGO-MoS2 fibres | resistive | NO2 | 53 ppb (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [185] |

| WS2 | impedance | methanol | 5.6 ppm (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [45] |

| WS2 | resistive | NO2 | 100 ppb in dry air | 150 | Partial oxidation of WS2 flakes. Humidity does not affect the sensing response | [193] |

| WS2 | resistive | H2 | 1 ppm in dry air | 150 | Partial oxidation of WS2 flakes. Humidity does not affect the sensing response | [193] |

| WS2 | resistive | NO2 | 8 ppb | 250 | Sensing tests in dry air | [194] |

| MTCNF-WS2 | resistive | NO2 | 10 ppb | RT | Sensing tests in dry air. Humidity affects the sensing response | [195] |

| Pd NPs-WS2 | resistive, flexible | H2 | 10 ppm | RT | Sensing tests in N2 atmosphere | [198] |

| Exfoliated BP | resistive | NO2 | 20 ppb | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [210] |

| Exfoliated BP | resistive | NO2 | 7 ppb (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in dry air | [212] |

| Exfoliated BP | resistive | NH3 | 80 ppb (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in N2 atmosphere and at 10 Torr | [214] |

| Pt NPs- exfoliated BP | FET | H2 | <2000 ppm (est.) | RT | Sensing tests in dry air. Pt-BP covered with PMMA. Selectivity to H2. | [223] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donarelli, M.; Ottaviano, L. 2D Materials for Gas Sensing Applications: A Review on Graphene Oxide, MoS2, WS2 and Phosphorene. Sensors 2018, 18, 3638. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/s18113638

Donarelli M, Ottaviano L. 2D Materials for Gas Sensing Applications: A Review on Graphene Oxide, MoS2, WS2 and Phosphorene. Sensors. 2018; 18(11):3638. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/s18113638

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonarelli, Maurizio, and Luca Ottaviano. 2018. "2D Materials for Gas Sensing Applications: A Review on Graphene Oxide, MoS2, WS2 and Phosphorene" Sensors 18, no. 11: 3638. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/s18113638