An Acute Case of Intoxication with Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxins in Recreational Water in Salto Grande Dam, Argentina

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Description of the Case

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Quantification of Phytoplankton and Microcystin in Water Sample

2.2. Acid-Base Status Parameters

2.3. Liver Injury Biomarkers

2.4. Renal Function Parameters

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Sampling Site and Analysis

3.2. Phytoplankton Analyses

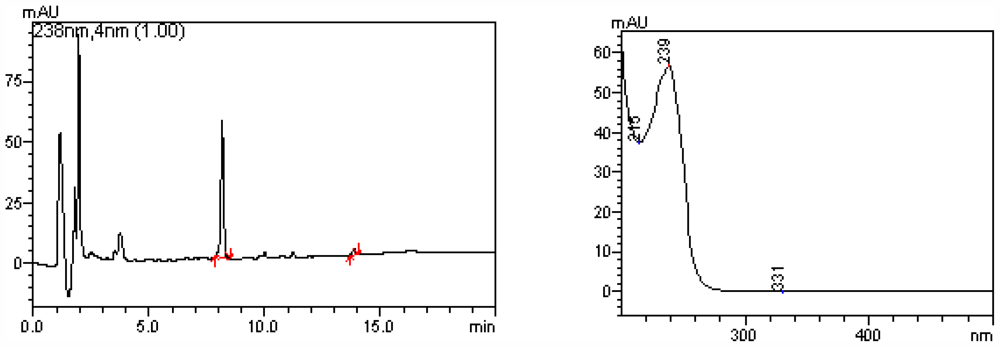

3.3. Microcystins Determination in Water Samples

3.4. Biochemical Parameters

3.5. Ionogram and Acid-Base Status Parameters

3.6. Liver and Renal Function Parameters

3.7. Hemogram

4. Conclusion

References

- Codd, G.A.; Lindsay, J.; Young, F.M.; Morrison, L.F.; Metcalf, J.S. Harmful Cyanobacteria. From Mass Mortalities to Management Measures. In Harmful Cyanobacteria; Huisman, J., Matthijs, H.C.P., Visser, P.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacKintosh, C.; Beattie, K.A.; Klumpp, S.; Cohen, P.; Codd, G.A. Cyanobacterial microcystin-LR is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A from both mammals and higher plants. FEBS Lett 1990, 264, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Gulledgea, B.M.; Aggena, J.B.; Huangb, H.B.; Nairnc, A.C.; Chamberlin, A.R. The microcystins and nodularins: cyclic polypeptide inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A. Curr. Med. Chem 2002, 9, 1991–2003. [Google Scholar]

- van Apeldoorn, M.E.; van Egmond, H.P.; Speijers, G.J.; Bakker, G.J. Toxins of cyanobacteria. Mol. Nutr. Food Res 2007, 51, 7–60. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, W.W.; Falconer, I.R. Diseases Related to Freshwater Blue Green Algal Toxins, and Control Measures. In Algal Toxins in Seafood and Drinking Water; Falconer, I.R., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1993; pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Backer, L.; McNeel, S.W.; Barber, T.; Kirkpatrick, B.; Williams, C.; Irvin, M.; Zhou, Y.; Johnson, T.B.; Nierenberg, K.; Aubel, M.; et al. Recreational exposure to microcystins during algal blooms in two California lakes. Toxicon 2010, 55, 909–921. [Google Scholar]

- Echenique, R.; Sedán, D.; Giannuzzi, L.; Niez-Gay, A.; Andrinolo, D. Impacto producido por floraciones de Cyanobacteria en agua de red (Concordia, Entre Ríos). In XXXII Jornadas Argentinas de Botánica; Sociedad Argentina de Botánica: Córdoba, Argentina, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, I.P.; Webb, M.; Schluter, P.J.; Shaw, G.R. Recreational and occupational field exposure to freshwater cyanobacteria—a review of anecdotal and case reports, epidemiological studies and the challenges for epidemiologic assessment. Environ. Health 2006, 5, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Backer, L.; Carmichael, W.; Kirkpatrick, B.; Williams, C.; Irvin, M.; Zhou, Y.; Johnson, T.B.; Nierenberg, K.; Hill, V.R.; Kieszak, S.M.; et al. Recreational exposure to low concentrations of Microcystins during an algal bloom in a small lake. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper-Goodman, T.; Falconer, I.; Fitzgerald, J. Human Health Aspects. Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water. In A Guide to Their Public Health Consequences, Monitoring and Management; Chorus, I., Bartram, J., Eds.; E & F Spon: London, UK, 1999; pp. 113–153. [Google Scholar]

- Amé, M.; Díaz, M.; Wunderlin, D. Occurrence of toxic cyanobacterial blooms in San Roque Reservoir (Córdoba, Argentina): A field and chemometric study. Environ. Toxicol 2003, 18, 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ruibal Conti, A.L.; Guerrero, J.M.; Regueira, J.M. Levels of microcystins in two Argentinean reservoirs used for water supply and recreation: differences in the implementation of safe levels. Environ. Toxicol 2005, 20, 263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Cazenave, J.; Wunderlin, D.A.; Bistoni, M.A.; Ame, M.V.; Krause, E.; Pflugmacher, S.; Wiegand, C. Uptake, tissue distribution and accumulation of Microcystin-RR in Corydoras paleatus, Jenynsia multidentata and Odontesthes bonariensis. Aquat. Toxicol 2005, 75, 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Andrinolo, D.; Pereira, P.; Giannuzzi, L.; Aura, C.; Massera, S.; Caneo, M.; Caixach, J.; Barco, M.; Echenique, R. Occurrence of Microcystis aeruginosa and microcystins in Rio de la Plata river (Argentina). Acta Toxicol. Argent 2007, 15, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ame, M.V.; Galanti, L.; Menone, M.; Gerpe, S.; Moreno, V.; Wunderlin, D. Microcystin-LR, -RR, -YR and -LA in water samples and fishes from a shallow lake in Argentina. Harmful Algae 2010, 9, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- De Leon, L.; Yunes, J. First report of a Microcystis aeruginosa toxic bloom in La Plata river. Environ. Toxicol 2001, 16, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ouahid, Y.; Zaccaro, M.; Zulpa, G.; Storni, M.; Stella, A.; Bossio, J.C.; Tanuz, M.; del Campo, F. A single microcystin in a toxic Microcystis bloom from the river Rio de Plata, Argentina. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem 2011, 91, 525–536. [Google Scholar]

- Echenique, R.; Rodríguez, J.; Caneo, M.; Gianuzzi, L.; Barco, M.; Rivera, J.; Caixach, J.; Andrinolo, D. Microcystins in the Drinking Water Supply in the Cities of Ensenada and La Plata (Argentina). Congresso Brasileiro de Ficología & Simposio Latino-Americano de Algas Nocivas, Itajaí, Brasil; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, Y.; Nagata, S.; Tsutsumi, T.; Hasegawa, A.; Watanabe, M.F.; Park, H.D.; Chen, G.C.; Chen, G.; Yu, S.Z. Detection of microcystins, a blue-green algal hepatotoxin, in drinking water sampled in Haimen and Fusui, endemic areas of primary liver cancer in China, by highly sensitive immunoassay. Carcinogenesis 1996, 17, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Jochimsen, E.M.; Carmichael, W.W.; An, J.S.; Cardo, D.M.; Cookson, S.T.; Holmes, C.E.M.; Antunes, M.B.; de Melo Filho, D.A.; Lyra, T.M.; Barreto, B.S.T.; et al. Liver failure in death after exposure to microcystins at a hemodialysis center in Brazil. N. Engl. J. Med 1998, 338, 873–878. [Google Scholar]

- Bury, N.R.; Newlands, A.D.; Eddy, F.B.; Codd, G.A. In vivo and in vitro intestinal transport of 3H-microcystin-LR, a cyanobacterial toxin, in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquat. Toxicol 1998, 42, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Solter, P.; Wollenberg, G.; Huang, X.; Chu, F.; Runnegar, M. Prolonged sublethal exposure to the protein phosphatase inhibitor MC-LR Results in multiple dose-dependent hepatotoxic effects. Toxicol. Sci 1998, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, R.E.; Solter, P.F. Characterization of sublethal microcystin-LR exposure in mice. Vet. Pathol 2002, 39, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Q.; Hua, Z.; Shen, P. Toxicology analysis of immunomodulating nitric oxide, iNOS and cytokines mRNA in mouse macrophages induced by microcystin-LR. Toxicology 2004, 197, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pahan, K.; Sheikh, F.; Namboodiri, A.; Singh, I. Inhibitors of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A differentially regulate the expression of inducible nitric-oxide synthase in rat astrocytes and macrophages. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 12219–12226. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, R.E.; Solter, P.F. Hepatic oxidative stress following prolonged sublethal microcystin LR exposure. Toxicol. Pathol 1999, 5, 582–588. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, I.; Pichardo, S.; Jos, A.; Gómez-Amores, L.; Mate, A.; Vazquez, C.M.; Cameán, A.M. Antioxidant enzyme activity and lipid peroxidation in liver and kidney of rats exposed to MC-LR administered intraperitoneally. Toxicon 2005, 45, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Andrinolo, D.; Sedan, D.; Telese, L.; Aura, C.; Masera, S.; Giannuzzi, L.; Marra, C.; Alaniz, M.T. Recovery after damage produced by subchronic intoxication with the cyanotoxin microcystin LR. Toxicon 2008, 51, 456–765. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Ong, C. Role of oxidative stress and mitochondrial changes in cyanobacteria-induced apoptosis and hepatotoxicity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 2003, 220, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, A.C.L.; Jorge, M.C.M.; Menezes, D.B.; Fonteles, M.C.; Monteiro, H.S.A. Effects of microcystin-LR in isolated perfused rat kidney. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res 1999, 32, 985–988. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, E.; Andrade, M.; Alverca, E.; Pereira, P.; Batoreu, M.C.; Jordan, P.; Silva, M.J. Comparative study of the cytotoxic effect of microcistin-LR and purified extracts from M. aeruginosa on a kidney cell line. Toxicon 2009, 53, 487–495. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, R.M.; Cagido, V.R.; Ferraro, R.B.; Meyer-Fernandes, J.R.; Rocco, P.R.; Zin, W.A.; Acevedo, S.M. Effects of microcystin-LR on mouse lungs. Toxicon 2007, 50, 330–338. [Google Scholar]

- Dillinberg, H.O.; Dehnel, M.K. Toxic waterbloom in Saskatchewan, 1959. Can. Med. Assoc. J 1960, 83, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, P.C.; Gammie, A.J.; Hollinrake, K.; Codd, G.A. Pneumonia associated with cyanobacteria. Br. Med. J 1990, 300, 1400–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, E.; Kondo, F.; Harada, K. First report on the distribution of orally administered microcystin-LR in mouse tissue using an immunostaining method. Toxicon 2000, 38, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, E.; Kondo, F.; Harada, K. Intratracheal administration of microcystin-LR and its distribution. Toxicon 2001, 39, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin, D.N.; Stoner, R.D.; Adams, W.H.; Kycia, J.H.; Siegelman, H.W. Atypical pulmonary thrombosis caused by a toxic cyanobacterial peptide. Science 1983, 220, 1383–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Andrinolo, D.; Sedán, D.; Telese, L.; Aura, C.; Masera, S.; Giannuzzi, L.; Marra, C.A.; Alaniz, M. Hepatic recovery after damage produced by sub-chronic intoxication with the cyanotoxin microcystin-LR. Toxicon 2008, 51, 457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Lance, E.; Josso, C.; Dietrich, D.; Ernst, B.; Paty, P.; Senger, F.; Bormans, M.; Gérard, C. Histopathology and microcystin distribution in Lymnaea stagnalis (Gastropoda) following toxic cyanobacterial or dissolved microcystin-LR exposure. Aquat. Toxicol 2010, 98, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xie, P.; Li, L.; Xu, J. First Identification of the hepatotoxic microcystins in the serum of a chronically exposed human population together with indication of hepatocellular damage. Toxicol. Sci 2009, 108, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Utermöhl, H. Zur Vervolkommung der quantitative Phytoplankton-Methodik. Mitt. Int. Verein. Limnol 1958, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Sübwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Ettl, H., Gärtner, G., Heyning, H., Mollenhauer, D., Eds.; Gustav Fischer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannuzzi, L.; Sedan, D.; Echenique, R.; Andrinolo, D. An Acute Case of Intoxication with Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxins in Recreational Water in Salto Grande Dam, Argentina. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 2164-2175. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/md9112164

Giannuzzi L, Sedan D, Echenique R, Andrinolo D. An Acute Case of Intoxication with Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxins in Recreational Water in Salto Grande Dam, Argentina. Marine Drugs. 2011; 9(11):2164-2175. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/md9112164

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannuzzi, Leda, Daniela Sedan, Ricardo Echenique, and Dario Andrinolo. 2011. "An Acute Case of Intoxication with Cyanobacteria and Cyanotoxins in Recreational Water in Salto Grande Dam, Argentina" Marine Drugs 9, no. 11: 2164-2175. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/md9112164