Suicide Risk among Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities: A Literature Overview

Abstract

:1. Introduction

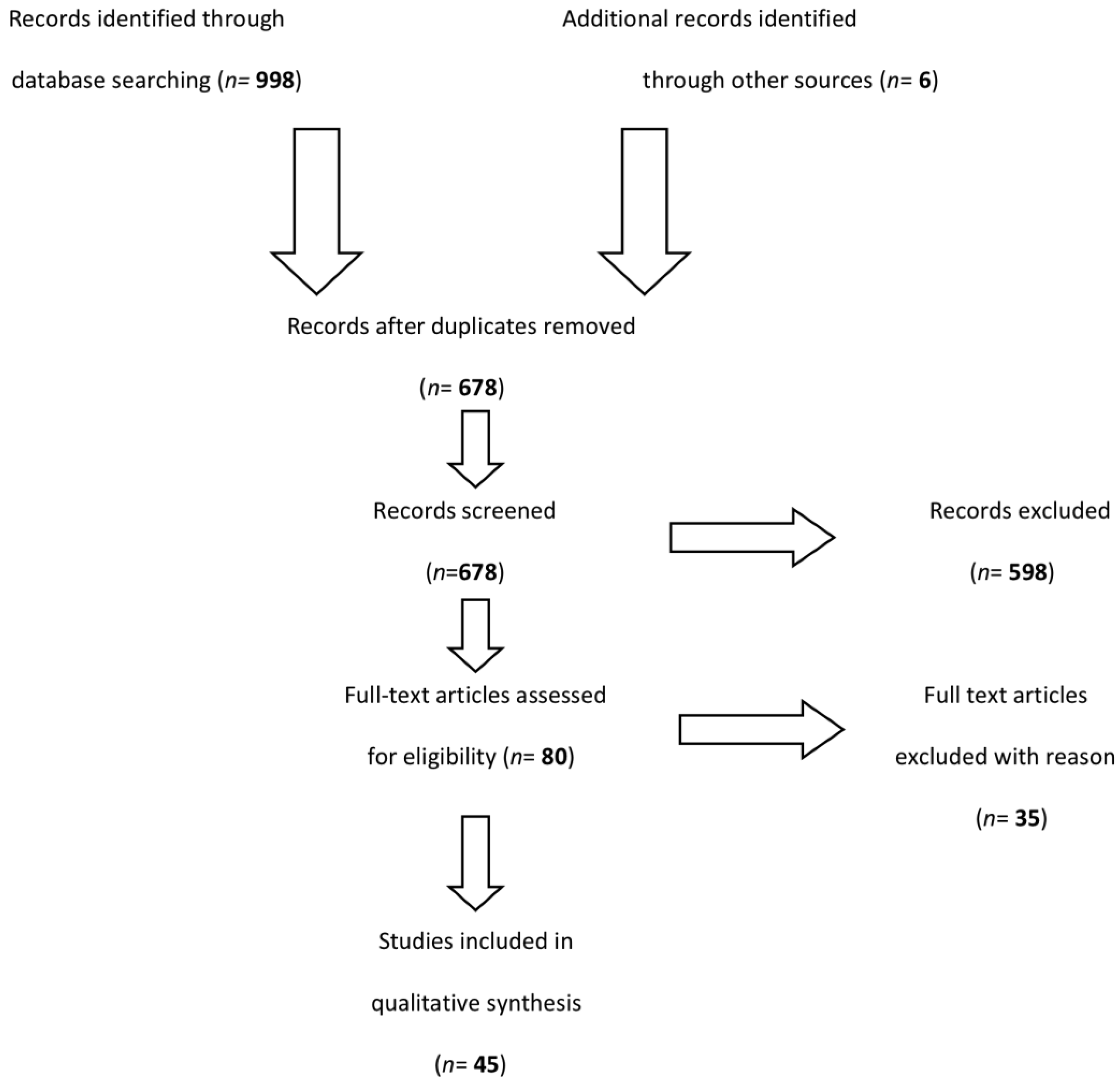

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Study Concept, Quality Assessment and Terminology

3. Results

3.1. Suicide Attempts and Ideation in Immigrants

3.2. Suicide Deaths in Immigrants

3.3. Suicidal Ideation and Attempt among Ethnic Minorities

3.4. Suicide Deaths in Ethnic Minorities

3.5. Cultural Stress as Risk Factor for Suicidal Behaviour in Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, A. The mental-health crisis among migrants. Nature 2016, 538, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carta, M.G.; Bernal, M.; Hardoy, M.C.; Haro-Abad, J.M.; The “Report on the Mental Health in Europe” Working Group. Migration and mental health in Europe (the state of the mental health in Europe working group: Appendix 1). Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2005, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straiton, M.; Reneflot, A.; Diaz, E. Immigrants’ use of primary health care services for mental health problems. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Derr, A.S. Mental Health Service Use among Immigrants in the United States: A Systematic Review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhugra, D.; Gupta, S.; Bhui, K.; Craig, T.; Dogra, N.; Ingleby, J.D.; Kirkbride, J.; Moussaoui, D.; Nazroo, J.; Qureshi, A.; et al. WPA guidance on mental health and mental health care in migrants. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gilliver, S.C.; Sundquist, J.; Li, X.; Sundquist, K. Recent research on the mental health of immigrants to Sweden: A literature review. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindert, J.; Ehrenstein, O.S.; Priebe, S.; Mielck, A.; Brähler, E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor-Graae, E.; Selten, J.-P. Schizophrenia and Migration: A Meta-Analysis and Review. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R.; Vigod, S.; Dennis, C.-L. Prevalence of postpartum depression among immigrant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 70, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spallek, J.; Reeske, A.; Norredam, M.; Nielsen, S.S.; Lehnhardt, J.; Razum, O. Suicide among immigrants in Europe—A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia Montesinos, A. Precipitating and risk factors for suicidal behavior among immigrants and ethnic minorities in Europe: A review of the literature. Suicidal Behav. Immigrants Ethn. Minor. Eur. 2015, 4, 60–80. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sharifi, A.; Krynicki, C.R.; Upthegrove, R. Self-harm and ethnicity: A systematic review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, L.C.; Ung, T.; Park, R.; Kwon, S.C.; Trinh-Shevrin, C. Risk Factors of Suicide and Depression among Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Youth: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2015, 26, 191–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abraído-Lanza, A.F.; Armbrister, A.N.; Flórez, K.R.; Aguirre, A.N. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.L.; Berry, J.W. Primary prevention of acculturative stress among refugees. Application of psychological theory and practice. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Res. Methods Rep. 2009, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.I.; Hales, R.E.; American Psychiatric Publishing. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management; American Psychiatric Pub: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR General Assembly Statute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for RefugeesStatute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 428 (V). Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/excom/bgares/3ae69ee64/statute-office-united-nations-high-commissioner-refugees.html (accessed on 6 July 2018).

- Šmihula, D. National minorities in the law of the EC/EU. Rom. J. Eur. Aff. 2008, 8, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, Y.K.; Ip, W.C. Suicidality and migration among adolescents in Hong Kong. Death Stud. 2007, 31, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Zhong, B.L.; Xiang, Y.T.; Chiu, H.F.K.; Chan, S.S.M.; Yu, X.; Caine, E.D. Internal migration, mental health, and suicidal behaviors in young rural Chinese. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoval, G.; Schoen, G.; Vardi, N.; Zalsman, G. Suicide in Ethiopian immigrants in Israel: A case for study of the genetic-environmental relation in suicide. Arch. Suicide Res. 2007, 11, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bergen, D.D.; Eikelenboom, M.; Smit, J.H.; van de Looij-Jansen, P.M.; Saharso, S. Suicidal behavior and ethnicity of young females in Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Rates and risk factors. Ethn. Health 2010, 15, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Termorshuizen, F.; Wierdsma, A.I.; Visser, E.; Drukker, M.; Sytema, S.; Laan, W.; Smeets, H.M.; Selten, J.P. Psychosis and suicide risk by ethnic origin and history of migration in the Netherlands. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 138, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Thiene, D.; Alexanderson, K.; Tinghög, P.; La Torre, G.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E. Suicide among First-generation and Second-generation Immigrants in Sweden: Association with Labour Market Marginalisation and Morbidity. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, C.K.; Kolves, K.; De Leo, D. Suicide mortality in second-generation migrants, Australia, 2001–2008. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kposowa, A.J.; McElvain, J.P.; Breault, K.D. Immigration and Suicide: The Role of Marital Status, Duration of Residence, and Social Integration. Arch. Suicide Res. 2008, 12, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Maskari, F.; Shah, S.M.; Al-Sharhan, R.; Al-Haj, E.; Al-Kaabi, K.; Khonji, D.; Schneider, J.D.; Nagelkerke, N.J.; Bernsen, R.M. Prevalence of depression and suicidal behaviors among male migrant workers in United Arab Emirates. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsicas, C.B.; Mäkinen, I.H.; Wasserman, D.; Apter, A.; Kerkhof, A.; Michel, K.; Renberg, E.S.; Van Heeringen, K.; Värnik, A.; Schmidtke, A. Repetition of attempted suicide among immigrants in Europe. Can. J. Psychiatry 2014, 59, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, L.M.; Sundquist, J.; Johansson, S.E.; Qvist, J.; Bergman, B. The influence of ethnicity and social and demographic factors on Swedish suicide rates. A four year follow-up study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1997, 32, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ryan, L.; Leavey, G.; Golden, A.; Blizard, R.; King, M. Depression in Irish migrants living in London: Case-control study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006, 188, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavey, G. Suicide and Irish migrants in Britain: Identity and integration. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 1999, 11, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L. Suicidal and Depressive Symptoms in Filipino Home Care Workers in Israel. J. Cross. Cult. Gerontol. 2012, 27, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, I.; Van Hemert, A.M.; Schudel, W.J.; Middelkoop, B.J.C. Suicidal Behavior in Four Ethnic Groups in the Hague, 2002–2004. Crisis 2009, 30, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duldulao, A.A.; Takeuchi, D.; Hong, S. Correlates of Suicidal Behaviors among Asian Americans. Arch. Suicide Res. 2009, 13, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhugra, D. Suicidal behavior in South Asians in the UK. Crisis 2002, 23, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.J.; Vaughan, E.L.; Liu, T.; Chang, T.K. Asian Americans’ proportion of life in the United States and suicide ideation: The moderating effects of ethnic subgroups. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2014, 5, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Lindesay, J.; Dennis, M. Suicides by country of birth groupings in England and Wales: Age-associated trends and standardised mortality ratios. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhui, K.S.; McKenzie, K. Rates and risk factors by ethnic group for suicides within a year of contact with mental health services in England and Wales. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, V.M.; Wingate, L.R.; Tucker, R.P.; Rhoades-Kerswill, S.; Slish, M.L.; Davidson, C.L. Interpersonal suicide risk for American Indians: Investigating thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2014, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheel, K.R.; Prieto, L.R.; Biermann, J. American Indian college student suicide: Risk, beliefs, and help-seeking preferences. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2011, 24, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.S.; Sugimoto-Matsuda, J.J.; Chang, J.Y.; Hishinuma, E.S. Ethnic differences in risk factors for suicide among American high school students, 2009: The vulnerability of multiracial and Pacific Islander adolescents. Arch. Suicide Res. 2012, 16, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, I.M.; Robinson, J.; Bickley, H.; Meehan, J.; Parsons, R.; McCann, K.; Flynn, S.; Burns, J.; Shaw, J.; Kapur, N.; et al. Suicides in ethnic minorities within 12 months of contact with mental health services. National clinical survey. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 183, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhui, K.S.; Dinos, S.; McKenzie, K. Ethnicity and its influence on suicide rates and risk. Ethn. Health 2012, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwena, J. Black and minority ethnic groups (BME) suicide, admission with suicide or self-harm: An inner city study. J. Public Health 2014, 22, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.L.; Utsey, S.O.; Bolden, M.A.; Williams, O. Do sociocultural factors predict suicidality among persons of African descent living in the U.S.? Arch. Suicide Res. 2005, 9, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, I.W.; Caine, E.D.; Barron, C.T.; Badaracco, M.A. Clinical and psychosocial profiles of Asian immigrants who repeatedly attempt suicide. Crisis 2015, 36, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagaman, A.K.; Sivilli, T.I.; Ao, T.; Blanton, C.; Ellis, H.; Lopes Cardozo, B.; Shetty, S. An Investigation into Suicides Among Bhutanese Refugees Resettled in the United States Between 2008 and 2011. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, D.K.; Foti, K.; Brener, N.D.; Crosby, A.E.; Flores, G.; Kann, L. Associations between risk behaviors and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: Do racial/ethnic variations in associations account for increased risk of suicidal behaviors among Hispanic/Latina 9th- to 12th-grade female students? Arch. Suicide Res. 2011, 15, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, J.B.; Wyman, P.A.; Brown, C.H.; Matthieu, M.M.; Olivares, T.E.; Hartel, D.; Zayas, L.H. Immigration generation status and its association with suicide attempts, substance use, and depressive symptoms among Latino adolescents in the USA. Prev. Sci. 2008, 9, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovey, J.D.; Magaña, C.G. Suicide Risk Factors among Mexican Migrant Farmworker Women in the Midwest United States. Arch. Suicide Res. 2003, 7, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.; Breslau, J.; Su, M.; Miller, M.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. Immigration and suicidal behavior among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorenson, S.B.; Shen, H. Mortality among young immigrants to California: Injury compared to disease deaths. J. Immigr. Health 1999, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.D.; Edelstein, A.; Vota, D. Suicidal ideation and alcohol use among ethiopian adolescents in Israel the relationshipwith ethnic identity and parental support. Eur. Psychol. 2012, 17, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichberger, M.C.; Heredia Montesinos, A.; Bromand, Z.; Yesil, R.; Temur-Erman, S.; Rapp, M.A.; Heinz, A.; Schouler-Ocak, M. Suicide attempt rates and intervention effects in women of Turkish origin in Berlin. Eur. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voracek, M.; Loibl, L.M.; Dervic, K.; Kapusta, N.D.; Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Sonneck, G. Consistency of immigrant suicide rates in Austria with country-of-birth suicide rates: A role for genetic risk factors for suicide? Psychiatry Res. 2009, 170, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, L.M.; Sundquist, J.; Johansson, S.E.; Bergman, B.; Qvist, J.; Träskman-Bendz, L. Suicide among foreign-born minorities and native swedes: An epidemiological follow-up study of a defined population. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. The Effect of Immigration on Suicide: A Cross-National Analysis. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 1981, 2, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burvill, P.W. Migrant suicide rates in Australia and in country of birth. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Värnik, A.; Kõlves, K.; Wasserman, D. Suicide among Russians in Estonia: Database study before and after independence. BMJ 2005, 330, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, M.J.; Rosato, M.; Teyhan, A.; Harding, S. Trends in suicide among migrants in England and Wales 1979–2003. Ethn. Health 2012, 17, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, R.; Morrell, S.; Slaytor, E.; Ford, P. Suicide in urban New South Wales, Australia 1985–1994: Socio-economic and migrant interactions. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, S.; Taylor, R.; Slaytor, E.; Ford, P. Urban and rural suicide differentials in migrants and the Australian-Born, New South Wales, Australia 1985–1994. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.; Morrell, S.; Taylor, R.; Carter, G.; Dudley, M. Divergent trends in suicide by socio-economic status in Australia. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ide, N.; Kõlves, K.; Cassaniti, M.; De Leo, D. Suicide of first-generation immigrants in Australia, 1974–2006. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 1917–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsicas, C.B.; Makinen, I.H.; Apter, A.; De Leo, D.; Kerkhof, A.; Lönnqvist, J.; Michel, K.; Renberg, E.S.; Sayil, I.; Schmidtke, A.; et al. Attempted suicide among immigrants in European countries: An international perspective. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, M.; Tan, C.H.; Sim, K.; Lau, G.; Mondry, A.; Leong, J.Y.; Tan, E.C. Epidemiology of completed suicides in Singapore for 2001 and 2002. Crisis 2007, 28, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, D. Explaining regional differences in suicide rates. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 40, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandrychyn, S. Geographic variation in suicide rates: Relationships to social factors, migration, and ethnic history. Arch. Suicide Res. 2004, 8, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, B.; Rousseau, C.; Slatkoff, J.; Lewkowski, M.; Davis, M.; Dube, S.; Lashley, M.E.; Morin, I.; Dray, P.; Harnden, B. Profile of a Metropolitan North American Immigrant Suicidal Adolescent Population. Can. J. Psychiatry 2006, 51, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malenfant, E.C. Suicide in Canada’s immigrant population. Health Rep. 2004, 15, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joiner, T.E. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Else, I.R.N.; Andrade, N.N.; Nahulu, L.B. Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Stud. 2007, 31, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsicas, C.B.; Mäkinen, I.H. Immigration and suicidality in the young. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.R.; Boden, J.M.; Rucklidge, J.J. The relationship between ADHD symptomatology and self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behaviours in adults: A pilot study. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2014, 6, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Quality Score | Country | Aim and Study Design | Sample | Attempt N | Suicide N | Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic minorities | ||||||||

| O’Keefe et al., 2014 [40] | I:1 II:1 III:0 IV:1 Total: 3 | USA | Investigated American Indian students’ suicidal ideation and its predictability. Observational study. | 171 | not reported | not reported | On-line survey. | Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness predict suicidal ideation in American Indians. |

| Scheel et al., 2011 [41] | I:1 II:1 III:0 IV:1 Total: 3 | USA | Examined American Indian college students’ suicidality. Cross-sectional survey. | 272 | not reported | not reported | Suicidal Risk Questionnaire (SRQ), Cultural commitment and demographic questionnaire, Suicide-related beliefs and help-seeking preferences questionnaire. | Suicidal ideation comparable with general college students. Low awareness of traditional tribal suicide (10%). Participants more committed to tribal culture prefer counselling from American Indian persons. |

| Wong et al., 2012 [42] | I:3 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 6 | USA | Investigated youth risk factors for suicide in ethnic minorities among American high school students. Cross-sectional survey | 88,532 | not reported | not reported | Data from the 1999–2009 Youth Risk Behaviour Surveys (YRBS), a national survey of high school students. Questionnaire. | Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander adolescents and multiracial adolescents have a higher prevalence of risk factors for suicide. |

| Hunt et al., 2003 [43] | I:1 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 5 | UK | Investigated suicides in ethnic minorities within 12 months of contact with mental health services in England and Wales. Clinical survey | 282 | not reported | 282 | Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and questionnaire. | Among patients from ethnic minorities who had been in contact with mental health services in the 12 months before death, suicide was characterised by: violent methods, first episode of self-harm, high rates of schizophrenia, unemployment, history of violence, and drug misuse |

| Bhui et al., 2012 [44] | I:2 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 6 | UK | Investigated the influence of ethnicity on suicide, and related risk indicators among suicidal patients in contact with psychiatric services. Retrospective. | 1358 | not reported | 1358 | Data from the United Kingdom’s Office for National Statistics between 1996 and 2001. Questionnaire. | Black African men have higher rates of suicide as compared with the white British group. Classical indicators of suicide risk are less common in black Africans and South Asians, as compared with the white British group. |

| Bhui et al., 2008 [39] | I:2 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 6 | UK | Investigated suicide rates, symptoms, and preventability of suicide among suicidal patients within 12 months of contact with mental health services. Retrospective. | 8029 | not reported | 8029 | Data from the United Kingdom’s Office for National Statistics. | Rates and SMRs varied across ethnic groups. |

| Ngwena, 2014 [45] | I:1 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 5 | UK | Investigated trends of suicides in black and minority ethnic (BME) groups. Retrospective. | 192 | not reported | 192 | Data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) and Public Health Observatory Mortality files, over the periods 2009–2012 and 2010–2013. | Suicides among patients from black and minority ethnic (BME) groups most prevalent in those of Arab origin and North or South Americans (28%), followed by those of Western and Eastern European origin (26%). |

| Walker et al., 2005 [46] | I:1 II:1 III:0 IV:1 Total: 3 | USA | Investigated the role of acculturation in suicidal-behaviour among African descendants living in the USA. Cross-sectional survey | 423 | - | not reported | African American Acculturation Scale (AAAS). The Multi-Dimensional Support Scale (MDSS). The Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) | Religious well being, and not acculturation, is predictive of suicidal ideation and history of suicide attempt. |

| Immigrants | ||||||||

| Continent of Origin: Asia | - | |||||||

| Chung et al., 2015 [47] | I:1 II:1 III:1 IV:1 Total: 4 | USA | Risks and protective factors among Asian immigrants who repeatedly attempt suicide. Mixed-method study: Study 1 = retrospective study and Study 2 = clinical survey. | Study 1 = 44 Study 2 = 12 | ≥2–5/persons | 0 | Retrospective study (n = 44: clinical records) and clinical survey (n = 12 semi-structured interviews). | Among Asian immigrants with repeated suicide attempts, risk factors are: hopelessness, social isolation, self-stigma, feelings of failure, and sense of rejection by own family. Protective factors: psychological well-being, feeling cared for and able to reciprocate care for others. |

| Bhugra et al., 2002 [36] | I:1 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 5 | UK | Collected information on inception rates of attempted suicides across all ethnic groups, in the UK. Cross-sectional survey. | 434 | 65 | 0 | Data from the 1991 census. Semi-structured interview (schedule assessing the attempt, culture identity schedule, life events, GHQ–28, and Clinical Interview Schedule–R). | South Asian women, especially those aged 18–24, have higher rates of attempted suicide, in association with high rates of cultural alienation and previous attempts. |

| Dai et al., 2015 [21] | I:2 II:1 III:1 IV:1 Total: 5 | China | Explored psychological consequences of internal migration among young rural Chinese and the associations between migrant status, mental health, and suicidal behaviours. Cross-sectional survey. | 1646 | 10 | 0 | Structured interview. Questionnaire (psycho-QOL subscale of the World Health Organization’s QOL Questionnaire—Brief Version; CEDS). | Socio-demographic and clinical variables, and social support, not migrant status, were the central determinants of mental health among all participants. Compared to their rural-residing peers, migrant workers had a decreased risk for depression and comparable risk for poor psycho-QOL and one-year serious suicide ideation. |

| Ayalon, 2012 [33] | I:1 II:1 III:1 IV:1 Total: 4 | Israel | Investigated suicidal and depressive symptoms along with exposure to abuse and perceived social support in Filipino home care workers in Israel. Cross-sectional survey. | 178 | 8 | - | Questionnaires (Paykel Suicide Scale; Patient Health Questionnaire-9). | The Filipino sample in Israel showed higher levels of suicide attempts compared to national statistics in the Philippines. Abuse within the home/work environment (35% of the sample) was predictive for depressive symptoms (3.4% depressed) |

| Hagaman et al., 2016 [48] | I:1 II:1 III:1 IV:1 Total: 4 | USA | Explored suicides among Bhutanese refugees in the USA. Cross-sectional survey. | 14 | not reported | 14 | Psychological autopsies, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSC). | Suicide among Bhutanese refugees is connected with experiences of family withdrawal, integration difficulties, and perceived lack of care. |

| Duldulao et al., 2009 [35] | I:2 II:2 III:1 IV:2 Total: 7 | USA | Investigated suicidal behaviours among Asian Americans, focusing on the correlates of suicidal ideation, plan, and attempt with nativity and gender. Prospective study. | 2095 | 52 | - | Interviews. Data from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS). | U.S.-born Asian American women showed higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide plan than U.S.-born Asian American men and immigrant Asian American men and women. |

| Wong et al., 2014 [37] | I:2 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 5 | USA | Explored the correlation between the proportion of life in the USA and suicide ideation among Asian Americans in order to address within-group ethnic variability. Cross-sectional survey. | 1332 | - | Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. | Asian Americans in the U.S. had higher rate of suicide ideation, with significant differences within ethnic groups: the highest rates were found in Korean Americans and the lowest in Indian Americans. | |

| Continent of Origin: The Americas | ||||||||

| Eaton, 2011 [49] | I:2 II:1 III:1 IV: 2 Total: 6 | USA | Investigated the associations between racial/ethnic variations and risk of suicidal behaviours among Hispanic/Latina female students. Cross-sectional survey. | 6322 | Total: 575 White 318 African american 101 Hispanic 161 | - | Data from The 2007 national school-based Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (YRBS); | Hispanic/Latina female students had a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation (21.1%) and suicide attempts (14.0%) than white and African American students. The risk behaviours associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were: injuries and violence; tobacco use; alcohol and drug use; sexual behaviours; perceived health status. |

| Peña et al., 2008 [50] | I:2 II:2 III:1 IV: 2 Total: 7 | USA | Investigated the associations between immigration generation status and suicide attempts, substance use and depressive symptoms among Latino adolescents in the USA. Cross-sectional survey (prospective cohort study). | 3135 | I generation 53 II generation 106 Later generation 153 | - | Data from The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Interviews. | Among Latino adolescents, immigrant generation status is determinant for suicide attempts. Second-generation U.S.-born Latino youths were 2.87 times more likely to have made suicide attempts as compared to foreign-born youth. Later generations of U.S.-born Latinos were 3.57 times more likely to have made suicide attempts as compared to first-generation Latino youths. |

| Hovey et al., 2003 [51] | I:1 II:2 III:0 IV: 1 Total: 4 | USA | Investigated suicide risk factors and depressive symptoms among Mexican migrant women farmworkers in the U.S. Midwest. Prospective study. | 20 | - | - | Interview and questionnaires (Adult Self- Perception Scale, Family Assessment Device, Beck Hopelessness Scale, SAFE Scale, The Personal Resource Questionnaire, Personality Assessment Inventory, Suicidal Ideation and Interview Topics, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). | Migrant women farmworkers presented elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. High depression symptoms were associated with: family dysfunction, ejective social support, hopelessness, and acculturative stress. High suicidal ideation was associated with lower self-esteem, family dysfunction, less ejective social support, hopelessness, acculturative stress. |

| Borges et al., 2009 [52] | I:2 II:1 III:1 IV: 2 Total: 6 | USA | Explored suicidal behaviour among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Retrospective study. | n1 = 5782; n2 = 1284 | - | 1284 | Data from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) (2001–2002; n1 = 5782) and the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES): (2001–2003; n2 = 1284). | Migration to the USA is a risk factor for suicidal behaviour among Mexican people. Risk for suicidal ideation: having a family member in the USA; having arrived in the USA before the age of 12, and being U.S.-born. Risk for suicide attempts: having a family member in the USA and being U.S.-born. |

| Sorenson et al., 1999 [53] | I:3 II:1 III:1 IV: 2 Total: 7 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | 38,166 | - | 1344 | Data from California Master Mortality. | The differences in mortality between foreign- and U.S.-born persons: young immigrants have lower or similar risk of death and they are underrepresented in suicides and overrepresented in homicides compared with U.S.-born persons. |

| Continent of Origin: Africa | ||||||||

| Shoval et al., 2007 [22] | I:0 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 4 | Israel | Investigated suicide in Ethiopian immigrants. | - | - | 25/100,000 | Data from National epidemiological surveys by the Israeli Ministry of Health. | High rates of suicide among Ethiopian immigrants in Israel, significantly higher than other immigrant populations. |

| Walsh et al., 2012 [54] | I:1 II:1 III:0 IV:1 Total: 3 | Israel | Investigated the relations between suicidal ideation and alcohol abuse with ethnic identity and parental support among Ethiopian adolescents in Israel. Cross-sectional survey. | 200 | - | - | Questionnaires. | Suicidal ideation correlates with ethnic identity, alcohol use and parental support. A strong positive ethnic identity plays a protective role against suicidal and risk behaviours. Among Ethiopian adolescents in Israel, Ethiopian identity correlates with lower levels of suicidal ideation and alcohol use. |

| Continent of Origin: Europe | ||||||||

| Aichberger et al., 2015 [55] | I:1 II:1 III:1 IV:1 Total: 4 | Germany | Investigated rates, motives and effectiveness of intervention-programs for suicidal behaviour among Turkish women in Berlin who made suicide attempts. Cross-sectional survey. | 159 | 159 | - | Questionnaires. | The high rate of suicide attempts among second-generation Turkish women in Berlin showed a significant reduction due to the application of the intervention program. |

| Ryan et al., 2006 [31] | I:1 II:2 III:0 IV:1 Total: 4 | UK | Explored depression and suicide rates in Irish migrants in London. Case–control study | 360 | - | - | Questionnaire (Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). | Irish migrants in London show higher rates of depression and suicide compared with other minority ethnic groups, especially when associated with poorly planned migration. This effect can be modified by positive post-migration experiences. |

| Shah et al. A, 2011 [38] | I:0 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 3 | UK | Examined suicide rates in England and Wales and its correlation with ethnicity. Retrospective. | - | - | - | Data from the Office of National Statistics. | Differences in suicide rates among ethnic groups: male suicide rates were higher in all ethnic groups, except in the Chinese group, and increased with ageing among Indians; female suicide rates were higher among Chinese and increased with ageing among the African and Chinese groups. |

| Voracek et al., 2009 [56] | I:3 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 7 | Austria | Investigated the role of genetic risk factors for suicide, comparing immigrant suicide rates in Austria with country-of-birth ones. Retrospective. | 65,206 | - | 65,206 | Data from Statistics Austria. | Immigrant and homeland suicide rates were significantly positively associated. This evidence confirms the existence of genetic risk factors for suicide specific for each population. |

| Termorshuizen et al., 2012 [24] | I:3 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 7 | Netherlands | Examined ethnic density and suicide risk among migrant groups in four big cities in the Netherlands. Retrospective cohort study. | 2,874,464 | - | 2572 | Data from Statistics Netherlands. | The ethnic density influenced suicide risk among ethnic groups. The presence of their own ethnic group in the neighbourhood has a positive effect on suicide risk among non-Western minorities. |

| Di Thiene et al., 2015 [25] | I:3 II:2 III:1 IV:2 Total: 8 | Sweden | Investigated differences in suicide between first- and second-generation immigrants in Sweden. Prospective population-based cohort study. | 4,034,728 | - | 4358 | Data from Statistics Swede: theNational Board of Health and Welfare. | The risk of suicide is lower in the first generation and higher in the second generation of immigrants compared with natives in Sweden. |

| Johansonn, 1997 [57] | I:3 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 6 | Sweden | Analysed the influence of ethnicity, age, sex, marital status, and date of immigration on suicide rates among immigrants in Sweden. Retrospective. | 6,725,274 | - | - | Data from Central Cause of Death Register. | Risk factors for suicide among immigrants in Sweden: ethnicity, being unmarried, male sex, age 45–54 or 75 and older, being born in Eastern Europe, Finland, or in non-European countries, and having immigrated to Sweden in 1967 or earlier. Males born in Russia/Finland and females born in Hungary/ Russia/ Finland/ Poland showed the highest risk ratios for suicide and higher risks than in their countries of birth. |

| Stack, 1981 [58] | I:0 II:2 III:0 IV:2 Total: 4 | USA | Examined the association between immigration and suicide. Systematic cross-national investigation. | - | - | - | Data from the World Bank. | The rate of immigration has effects on the incidence of suicide: 1% increase in immigration is associated with a 13% increase in the rate of suicide. |

| Burvill, 1998 [59] | I:3 II:2 III:0 IV:1 Total: 6 | Australia | Investigate suicide rates in migrant groups to Australia from Britain, Ireland, and the rest of Europe for the years 1979–1990. Epidemiological study. | - | - | - | Data from the Australian Bureau of statics (ABS) and the World Health Organization Annual Statistics between 1979 and 1990. | Comparison between the Australian-born and migrants from 11 European countries showed increased rates in immigrants compared with those in their country of birth (COB), and a significant rank correlation of the immigrant rates with those in their COB. |

| Värnik et al., 2005 [60] | I:3 II:2 III:0 IV:1 Total: 6 | Estonia | Investigated changes in suicide rates among Russians in Estonia before (1983–1990) and after (1991–1998) Estonian independence from the Soviet Union. Epidemiological study. | - | - | - | Data from the World Health Organization and the Estonian Statistical Office. | Significantly higher suicide rate in Estonian Russians after Estonian independence in 1991, as compared to that of Estonians and Russians in Russia. The loss of privileged status of Russians during the Soviet era led to increasing suicide rates. |

| Maynard et al., 2012 [61] | I:0 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 3 | UK | Analysed suicide in England and Wales among immigrants. Cross-sectional survey. | 0 | Data from The Office for National Statistics (ONS). | This study indicated declining trends of suicide rates for most migrant groups and for English and Welsh-born women, but adverse trends for some country of birth groups. | ||

| Continent of Origin: Australia | ||||||||

| Taylor et al., 1998 [62] | I:0 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 3 | Australia | Examined the differences in suicide by socio-economic status (SES) in urban areas of Australia. Retrospective. | - | - | - | Data from the NSW unit record mortality tape, from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). | Risk of suicide in females was 28% that of males in adults, and 21% for youth. The risk increased significantly with decreasing socio-economic status in males, but not in females and depended on the country of origin. |

| Morrell et al., 1999 [63] | I:0 II:2 III:0 IV:2 Total: 4 | Australia | Examined the differences in suicide rates between urban and rural areas of Australia among immigrants. Population-study. | - | - | - | Epidemiological data on the entire Australia population. | The higher rates of suicide in older males in non-metropolitan areas of Australia is mainly due to the high migrant suicide rates in these regions, but the same it is not true for the higher rates of male youth suicide in non-metropolitan areas. |

| Page et al., 2006 [64] | I:0 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 3 | Australia | Examined the correlation between trends in suicide and socio-economic status (SES) in Australia. Cross-sectional survey. | - | - | - | Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) | Socio economic status (SES) influenced suicide rates in Australia and the suicide rate was higher in low-SES males. The suicide rate was lower in young males in middle and high SES groups. |

| Law, 2014 [26] | I:2 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 6 | Australia | Investigated suicide rates in second-generation migrants in Australia. Cross-sectional survey. | 5541 | - | 5541 | Data obtained from the National Coroners’ Information System (NCIS). | Second-generation migrants in Australia had a lower suicide risk compared to first-generation migrants or locals (third-plus-generation), and this evidence could be explained by their better socioeconomic status. |

| Ide et al., 2012 [65] | I:3 II:2 III:0 IV:2 Total: 7 | Australia | Investigated suicide of first-generation immigrants in Australia between 1974 and 2006. Epidemiological study. | - | - | - | Data from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). | First-generation male migrants in Australia had suicide rates that correlated to those of their countries of birth (COB), but not females. Rates are probably influenced by cultures, traditions, ethnicities, and the genetic predispositions of their home country. All COB groups showed suicide rates decreasing in time. |

| Lipsicas et al., 2012 [66] | I:3 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 6 | EU | Investigated suicide among immigrants in European countries. Cross-sectional survey. | 27,048 | - | - | Data from the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Suicidal Behaviour | Immigrants in European countries showed significantly higher suicide-attempt rates (SARs) than their hosts and had similar rates across different European countries as well as country-of-origin suicide rate. |

| Loh et al., 2007 [67] | I:1 II:1 III:1 IV:2 Total: 6 | Singapore | Analysed suicide in Singapore. Cross-sectional survey. | 640 | - | 640 | Data from the Center for Forensic Medicine database. | The suicide patterns in Singapore showed a few changes with the passing of time. The characteristics that remained constant for suicides were: low prevalence for teenagers, higher prevalence for older adults, male/female ratio, and method of jumping from heights. Factors with increased prevalence were: unemployment and history of psychiatric disorder. |

| Lester, 1995 [68] | I:0 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 3 | USA | Retrospective. | Data obtained from Kramer et al. Predictor variables obtained from the Census Bureau. | The suicide rate of those born in non-contiguous states of America and abroad is predicted by social characteristics. | |||

| Kandrychyn, 2004 [69] | I:0 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 3 | Russia | Investigated how suicide rates vary in each geographic area due to social factors, migration, and ethnicity. Retrospective. | - | - | - | Data from the publication of Goskomstat—the Russian State Statistics Committee. | The suicide rates vary through Russian Federation and are higher in the north because of the historical prevalence of the Finno-Ugrian component in the north of the country. |

| Greenfield, 2006 [70] | I:1 II:2 III:1 IV:1 Total: 5 | USA | Examine suicide among North American adolescent immigrant population. Prospective. | 344 | 344 | - | Questionnaire | Canadian immigrant adolescents presented lower suicide rates compared to non-migrant ones, and this is due to a lower rate of reported drug use among immigrants. |

| Kwan et al., 2007 [20] | I:2 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 5 | China | Examined suicide among Hong Kong adolescents. Cross-sectional survey. | 4540 | - | - | Questionnaire. Data from Census & Statistics Department. | This study indicated that suicide rates among immigrant adolescents in Hong Kong depend on duration of residence: short-duration (<10 years) correlated with lower suicide rates, and long-duration (>10 years or more) with higher suicide rates than the local-born counterparts. |

| Malenfant et al., 2004 [71] | I:0 II:1 III:0 IV:2 Total: 3 | Canada | Examined suicide among Canadian immigrants. Cross-sectional survey. | - | - | - | Data from the Canadian Vital Statistics Data Base and the World Health Statistics Annual of the World Health Organization. | This study examined differences in suicide rates between immigrants and non-immigrant Canadian residents. Immigrants had 50% lower suicide rates, which increased with age and involved predominately males. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forte, A.; Trobia, F.; Gualtieri, F.; Lamis, D.A.; Cardamone, G.; Giallonardo, V.; Fiorillo, A.; Girardi, P.; Pompili, M. Suicide Risk among Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities: A Literature Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1438. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15071438

Forte A, Trobia F, Gualtieri F, Lamis DA, Cardamone G, Giallonardo V, Fiorillo A, Girardi P, Pompili M. Suicide Risk among Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities: A Literature Overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(7):1438. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15071438

Chicago/Turabian StyleForte, Alberto, Federico Trobia, Flavia Gualtieri, Dorian A. Lamis, Giuseppe Cardamone, Vincenzo Giallonardo, Andrea Fiorillo, Paolo Girardi, and Maurizio Pompili. 2018. "Suicide Risk among Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities: A Literature Overview" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 7: 1438. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph15071438