The Effect of Social Communication on Life Satisfaction among the Rural Elderly: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

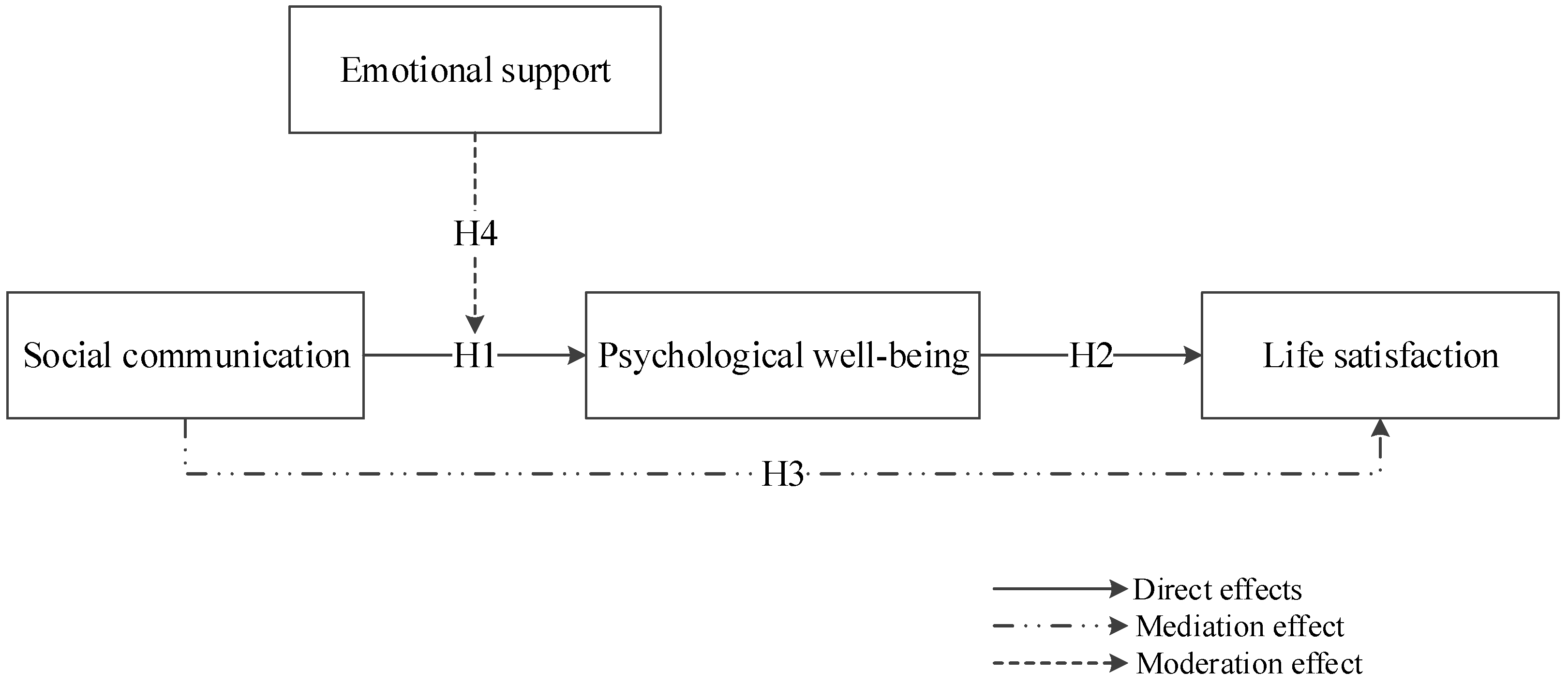

2. Theory Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. The Mediating Role of Psychological Well-Being

2.1.1. Social Communication and Psychological Well-Being

2.1.2. Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction

2.1.3. Social Communication, Psychological Well-Being, and Life Satisfaction

2.2. The Moderating Effect of Emotional Support

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Common Method Variance

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Partial Questionnaire

| Constructs | Items |

|---|---|

| Social communication | Do you often go to your neighbor’s house to chat or go out to chat with people in the village? 1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes 4 = often, 5 = everyday |

| Who usually chat with you? 1 = children, 2 = relatives, 3 = neighbors, 4 = friends | |

| Psychological well-being (1 = disagree; 5 = agree) | I feel good every day. |

| I feel like every day is fine. | |

| I find life interesting. | |

| I often feel lonely. | |

| I always feel sad in my heart. | |

| I always feel old and useless. | |

| Now, I always feel like I have nothing to do. | |

| I always feel like I don’t want to eat, and it’s tasteless. | |

| I can’t sleep well (dream a lot/wake up early/insomnia). | |

| Emotional support (1 = disagree; 5 = agree) | All things considered, you feel very close to your children. |

| Generally speaking, you feel that you get along well with your children. | |

| When you talk to your child about your worries or difficulties, you think he/she is willing to listen to you pour out them. | |

| Life satisfaction (1 = disagree; 5 = agree) | In most cases my life is close to what I want to have. |

| My living conditions are very good | |

| I am satisfied with my life | |

| By far, I’ve got the most important thing I ever wanted in my life. | |

| If I had my life to live over, I would change almost nothing. |

References

- LI, X.R. Steady Growth of the Total Population Steady Improvement of Urbanization Level. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj./sjjd/201901/t20190123_1646380.html (accessed on 23 January 2019).

- Bhattarai, K.; Budd, D. Effects of rapid urbanization on the quality of life. In Multidimensional Approach to Quality of Life Issues: A Spatial Analysis; Braj Raj Kumar, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.-J.; Du, W.-T.; Liu, Y.-C.; Guo, L.-N.; Zhang, J.-J.; Qin, M.-M.; Liu, K. Loneliness, stress, and depressive symptoms among the chinese rural empty nest elderly: A moderated mediation analysis. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 1, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, K.; Khan, H.T.A. Exploring the relationship between social support and life satisfaction among rural elderly in japan. Ageing Int. 2016, 4, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y. Personal life satisfaction of China’s rural elderly: Effect of the new rural pension programme. J. Int. Dev. 2017, 1, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.Y.; Su, X.R.; Wu, J.J. The satisfaction level of the needs of the rural elderly affects their life satisfaction: The mediating effect of loneliness. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Education and Social Science (ICESS 2019), Shenyang, China, 29 March 2019; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, E.W. Newcomers’ relationships: The role of social network ties during socialization. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 6, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, P.H.; Norman, D.A. Human Information Processing: An Introduction to Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zur, H. Coping styles and affect. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2009, 2, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hou, Y.; Sun, M.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Chang, F.; Hao, M. An evaluation of China’s new rural cooperative medical system: Achievements and inadequacies from policy goals. BMC Public Health 2015, 1, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phibbs, S.; Stawski, R.S.; MacDonald, S.W.S.; Munoz, E.; Smyth, J.M.; Sliwinski, M.J. The influence of social support and perceived stress on response time inconsistency. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 2, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfani, S.S.; Abedin, B. Impacts of the use of social network sites on users’ psychological well-being: A systematic review. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.H.; Geng, Y.H. Research on social communication between migrant workers and citizens and its influence on psychological integration of migrant workers. Stud. Pract. 2007, 7, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Aboderin, I. Decline in material family support for older people in urban Ghana, Africa: Understanding processes and causes of change. J. Gerontol. 2004, 3, S128–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwell, L.; Bengtson, V.L. Geographic distance and contact between middle-aged children and their parents: The effects of social class over 20 years. J. Gerontol. 1997, 1, S13–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, L.; Fu, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wu, H.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, L. Socio-economic factors related with the subjective well-being of the rural elderly people living independently in China. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.N.; Zeng, Y. Dynamic changes of individual social and economic characteristics and self-care ability of the Oldest-Old. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2004, S1, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 6, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarotti, S.; Biassoni, F.; Villani, D.; Prunas, A.; Velotti, P. Individual differences in cognitive emotion regulation: Implications for subjective and psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 1, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 4, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Feng, H.; Yuan, Q.; He, G.P. The effect of nostalgic group psychological intervention on depressive symptoms and life satisfaction of the elderly in the community. Chin. J. Gerontol. 2011, 3, 386–388. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Wu, M.; Xie, H.; Zhang, J.; Jia, J.; Su, Y. Social support moderates the effects of self-esteem and depression on quality of life among Chinese rural elderly in nursing homes. Arch. Psychiat. Nurs. 2017, 2, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cage, E.; Di Monaco, J.; Newell, V. Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 2, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Houlfort, N.; Vallerand, R.; Krantz, D. Emphasizing the self in organizational research on self-determination theory. In The Self at Work: Fundamental Theory and Research; Ferris, D.L., Johnson, R.E., Sedikides, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 145–171. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney, B.C.; Collins, N.L. A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 2, 113–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Chua, B.L.; Yeung, A.S.; Ryan, R.M.; Chan, W.Y. The importance of autonomy support and the mediating role of work motivation for well-being: Testing self-determination theory in a Chinese work organisation. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 4, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.H.; Cai, F.W. Social communication and mental health of new generation migrant workers—An empirical analysis based on survey data from Beijing and pearl river delta regions. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2012, 4, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Jia, Y.J. The influence of social communication on the health self-evaluation of rural elderly women: Based on the survey of shaanxi province. J. Humanit. 2010, 4, 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. On the relationship between human’s social communication and human’s essence and development. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. 1996, 4, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.X. Research on the relationship between social support and life satisfaction of the elderly. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2004, S1, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.X. Social support and quality of life of the elderly in China. Popul. Res. 2007, 3, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.X.; Yu, X.J.; Wang, G.Z.; Liu, H.Y. Desires and practices for old-age support in China. Popul. Econ. 2004, 5, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn, M. The effects of ageing on intergenerational support exchange: A new look at the hypothesis of flow reversal. Eur. J. Popul. 2019, 2, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhenhui, C. Intergenerational relations and subjective well-being among Chinese oldest-old. Chin. Stud. 2016, 2, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.T. Native Chinese Birth System; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Ai, B. A study of the social communication of the urban elderly people in Tibet. J. Yunnan Univ. Natl. 2012, 4, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Wei, L.I. Construction of social support system based on psychological needs of left-behind elderly in rural areas. J. Chongqing Univ. 2018, 1, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Li, S.Z. The effect of intergenerational support on physical health of rural elderly under the background of out-migration of young adults. Popul. Dev. 2012, 2, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 3, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 1, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 4, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, D.; Judd, C.M.; Yzerbyt, V.Y. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 6, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.J.; Wen, Z.l. A discussion on testing methods for mediated moderation models: Discrimination and integration. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2013, 9, 1050–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Y. The relationship of college students’ social support and well-being: The mediating role of social self-esteem. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2014, 3, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Age | −0.048 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. Spouse situation | −0.001 | −0.025 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4. Housing situation | 0.009 | 0.030 | 0.020 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5. Social communication | −0.004 | −0.054 | 0.065 | 0.146 ** | (0.807) | - | - | - |

| 6. Emotional support | 0.068 | 0.011 | 0.232 ** | 0.040 | 0.409 ** | (0.807) | - | - |

| 7. Life satisfaction | 0.013 | −0.010 | 0.145 ** | −0.022 | 0.389 ** | 0.617 ** | (0.794) | - |

| 8. Psychological well-being | 0.000 | −0.016 | 0.084 | 0.070 | 0.599 ** | 0.537 ** | 0.526 * | (0.773) |

| M | 0.5 | 71.12 | 1.16 | 1.83 | 4.89 | 3.69 | 2.99 | 3.48 |

| SD | 0.501 | 40.87 | 0.784 | 0.387 | 1.25 | 1.03 | 1.17 | 0.91 |

| Min | 0 | 60 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Max | 1 | 95 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Model | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model | 2.673 | 0.949 | 0.940 | 0.071 |

| M1 | 5.659 | 0.874 | 0.853 | 0.095 |

| M2 | 5.324 | 0.883 | 0.864 | 0.092 |

| M3 | 6.981 | 0.838 | 0.811 | 0.108 |

| M4 | 8.087 | 0.807 | 0.776 | 0.118 |

| M5 | 8.828 | 0.787 | 0.753 | 0.124 |

| M6 | 10.034 | 0.754 | 0.715 | 0.133 |

| M7 | 8.393 | 0.799 | 0.767 | 0.120 |

| Model | Ma | Mb | Mc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Y: life satisfaction | W: psychological well-being | Y: life satisfaction |

| Social communication(X) | 0.394 (0.000) | 0.588 (0.037) | 0.242 (0.022) |

| Emotional support(U) | 0.638 (0.000) | 0.528 (0.047) | 0.639 (0.000) |

| Social communication × emotional support (UX) | −0.300 (0.020) | −0.356 (0.000) | −0.278 (0.043) |

| Psychological well-being (W) | - | - | 0.140 (0.228) |

| Path | Indirect Effect | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LL95%CI | UL95%CI | ||

| Social communication-psychological well-being-life satisfaction | 0.110 | 0.061 | 0.157 |

| Social communication × emotional support-psychological well-being-life satisfaction | 0.075 | 0.052 | 0.103 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Feng, S. The Effect of Social Communication on Life Satisfaction among the Rural Elderly: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3791. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16203791

Chen Y, Yang C, Feng S. The Effect of Social Communication on Life Satisfaction among the Rural Elderly: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(20):3791. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16203791

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yashuo, Chunjiang Yang, and Shangjun Feng. 2019. "The Effect of Social Communication on Life Satisfaction among the Rural Elderly: A Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 20: 3791. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16203791