Diverged Preferences towards Sustainable Development Goals? A Comparison between Academia and the Communication Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

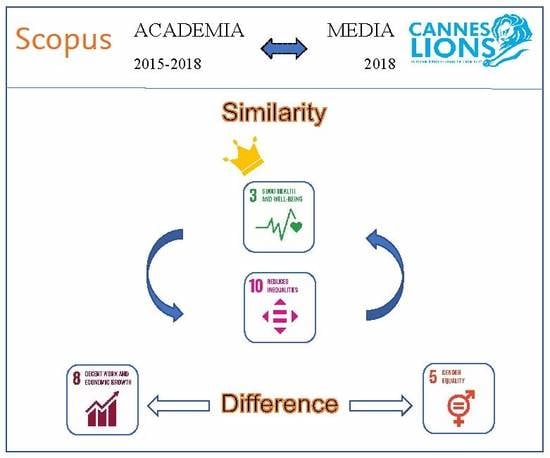

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Annual and Total Features of Academic Publications for Each SDG

3.2. The Preference of Communication Communities in 2018 SDG Lions

3.3. The Comparison of Influential SDGs between Academia and Communication Industries in 2018

3.4. The Frequency Analysis of Tied Pairs in the 17-goal Network

3.5. The Correlation Strength of Each of the SDG 3 Pairs

3.6. The Multiple Connections of SDGs in Academic Publications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Le Blanc, D. Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) Earth Summit. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/milestones/unced (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Gore, C. The post-2015 moment: Towards sustainable development goals and a new global development paradigm. J. Int. Dev. (DSA Conf. Spec. Issue) 2015, 27, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future Earth. Available online: http://futureearth.org/sites/default/files/2016_report_contribution_ science_sdgs.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Pradhan, P.; Costa, L.; Rybski, D.; Lucht, W.; Kropp, J. A systematic study of sustainable development goal (SDG) interactions. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Kanie, N.; Kim, R.E. Global governance by goal-setting: The novel approach of the UN sustainable development goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the interactions between sustainable development goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Chisholm, E.; Griggs, D.; Howden-Chapman, P.; McCollum, D.; Messerli, P.; Neumann, B.; Stevance, A.; Visbeck, M.; Stafford-Smith, M. Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: Lessons learned and ways forward. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1489–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Science Council. Available online: https://council.science/cms/2017/05/SDGs-Guide-to-Interactions.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- McCollum, D.L.; Echeverri, L.G.; Busch, S.; Pachauri, S.; Parkinson, S.; Rogelj, J.; Krey, V.; Minx, J.C.; Nilsson, M.; Stevance, A.; et al. Connecting the sustainable development goals by their energy inter-linkages. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 033006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.G.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Swartz, W.; Cheung, W.; Guy, J.A.; Kenny, T.; McOwen, C.J.; Asch, R.; Geffert, J.L.; Wabnitz, C.C.C.; et al. A rapid assessment of co-benefits and trade-offs among sustainable development goals. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Water. Available online: http://www.unwater.org/publications/water-sanitation-interlinkages-across-2030-agenda-sustainable-development (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Vladimirova, K.; Le Blanc, D. Exploring links between education and sustainable development goals through the lens of UN flagship reports. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collste, D.; Pedercini, M.; Cornell, S.E. Policy coherence to achieve the SDGs: Using integrated simulation models to assess effective policies. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, M.; Cranmer, C.; Lawford, R.; Engel-Cox, J. Toward an understanding of synergies and trade-offs between water, energy, and food SDG targets. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhamo, L.; Ndlela, B.; Nhemachena, C.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Mpandeli, S.; Matchaya, G. The water-energy-food nexus: Climate risks and opportunities in Southern Africa. Water 2018, 10, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Nilsson, M. Toward a multi-level action framework for sustainable development goals. In Governing Through Goals: Sustainable Development Goals as Governance Innovation, 1st ed.; Kanie, N., Biermann, F., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9780262533195. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, T.R.; Crootof, A.; Scott, C.A. The water-energy-food nexus: A systematic review of methods for nexus assessment. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 043002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Cudennec, C.; Gain, A.K.; Hoff, H.; Lawford, R.; de Strasser, J.Q.L.; Yillia, P.T.; Zheng, C. Challenges in operationalizing the water-energy-food nexus. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2017, 62, 1714–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Tsurita, I.; Burnett, K.; Orencio, P.M. A review of the current state of research on the water, energy, and food nexus. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2017, 11, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_WI_WaterSecurity_ WaterFoodEnergyClimateNexus_2011.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-bl496e.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Leal Filho, W.; Azeiteiro, U.; Alves, F.; Pace, P.; Mifsud, M.; Brandli, L.; Caeiro, S.S.; Disterheft, A. Reinvigorating the sustainable development research agenda: The role of the sustainable development goals (SDG). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World. 2018, 25, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Initial progress in implementing the sustainable development goals (SDGs): A review of evidence from countries. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Group. Available online: https://undg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/UNDG-Mainstreaming-the-2030-Agenda-Reference-Guide-2017.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2018).

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D.; Hillier, D. Common ground: The sustainable development goals and the marketing and advertising industry. J. Pub. Affairs 2018, 18, e1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, P.; Lopez, C. Out of the loop: Why research rarely reaches policymakers and the public and what can be done. Biotropica 2009, 41, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, S.; Mao, F.; Buytaert, W. Environmental data visualization for non-scientific contexts: Literature review and design framework. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2016, 85, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibeck, V.; Neset, T.S.; Linnér, B.O. Communicating climate change through ICT-based visualization: Towards an analytical framework. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4760–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.; Zweigenthal, V.; Olivier, J. Evidence map of knowledge translation strategies, outcomes, facilitators and barriers in African health systems. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2019, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körfgen, A.; Förster, K.; Glatz, I.; Maier, S.; Becsi, B.; Meyer, A.; Kromp-Kolb, H.; Stötter, J. It’s a hit! Mapping Austrian research contributions to the sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, A.L.; Filho, W.L.; Brandli, L.L.; Griebeler, J.S. Assessing research trends related to sustainable development goals: Local and global issues. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Methodology. Available online: https://research-methodology.net/sampling-in-primary-data-collection/snowball-sampling (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Lindblom, C.E. The Policy-Making Process, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M.; Shaw, D. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Pub. Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.W.; Gaskell, G. Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook, 1st ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2000; pp. 131–151. ISBN 9780761964810. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Freeman, L.C. UCINET for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis, 1st ed.; Analytic Technologies: Harvard, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psycho. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. Available online: http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm (accessed on June 2019). [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.A.; Nisbet, M.C.; Maibach, E.W. A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Clim. Chang. 2012, 113, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, K.T.; Garrett, R.K.; Slater, M.D. Promoting persuasion with ideologically tailored science messages: A novel approach to research on emphasis framing. Sci. Commun. 2019, 41, 488–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brolan, C.E.; Hill, P.S. Sexual and reproductive health and rights in the evolving post-2015 agenda: Perspectives from key players from multilateral and related agencies in 2013. Reprod. Health Matter. 2014, 22, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.S.; Buse, K.; Brolan, C.E.; Ooms, G. How can health remain central post-2015 in a sustainable development paradigm? Glob. Health 2014, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodney, A.M.; Hill, P.S. Achieving equity within universal health coverage: A narrative review of progress and resources for measuring success. Int. J. Qual. Health. 2014, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Bergen, N.; Schlotheuber, A. Promoting health equity: WHO health inequality monitoring at global and national levels. Glob. Health Act. 2015, 8, 29034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1758GSDR%202015%20Advance%20Unedited%20Version.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Biggeri, M.; Clark, D.A.; Ferrannini, A.; Mauro, V. Tracking the SDGs in an integrated manner: A proposal for a new index to capture synergies and trade-offs between and within goals. World Dev. 2019, 122, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, E. No Turning Back: The History of Feminism and the Future of Women, 1st ed.; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0345450531. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Emma Watson: Gender Equality Is Your Issue Too. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2014/9/emma-watson-gender-equality-is-your-issue-too (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- The Guardian. Meryl Streep Urges Congress to Back Equal Rights Amendment. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jun/23/meryl-streep-congress-equal-rights-amendment (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Chadwick, A.; Dennis, J.; Smith, A.P. Politics in the Age of Hybrid Media: Power, Systems, and Media Logics, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 7–22. ISBN 9781138860766. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, R.E.; Trent, J.S.; Friedenberg, R.V. Political Campaign Communication: Principles and Practices, 1st ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2019; pp. 293–359. ISBN 1538112604. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. The sustainable development goals and the systems approach to sustainability. Economics 2017, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waage, J.; Yap, C.; Bell, S.; Levy, C.; Mace, G.; Pegram, T.; Unterhalter, E.; Dasandi, N.; Hudson, D.; Kock, R.; et al. Governing the UN sustainable development goals: Interactions, infrastructures, and institutions. In Thinking Beyond Sectors for Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; Waage, J., Yap, C., Eds.; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, J.; Guo, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, W.; Xiang, Y. Information and communications technologies for sustainable development goals: State-of-the-art, needs and perspectives. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 2018, 20, 2389–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ford, M. The functions of higher education. Am. J. Econ. Soc. 2017, 76, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. ‘The degree is not enough’: Students’ perceptions of the role of higher education credentials for graduate work and employability. Brit. J. Sociol. Educ. 2008, 29, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1979, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhong, J.; Pan, Y. Predicting essential proteins based on weighted degree centrality. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2014, 11, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G. A Graph-theoretic perspective on centrality. Soc. Netw. 2006, 28, 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sade, D.S. Sociometrics of macaca mulatta Ⅲ: N-path centrality in grooming networks. Soc. Netw. 1989, 11, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/events/meetings/2015/un-sustainable-development-summit/en (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Nunes, A.R.; Lee, K.; O’Riordan, T. The importance of an integrating framework for achieving the sustainable development goals: The example of health and well-being. BMJ Glob. Health 2016, 1, e000068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Policy: Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baziliana, M.; Rognerb, H.; Howellsc, M.; Hermannc, S.; Arentd, D.; Gielene, D.; Stedutof, P.; Muellerf, A.; Komorg, P.; Tolh, R.S.J.; et al. Considering the energy, water and food nexus: Towards an integrated modelling approach. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7896–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giupponi, C.; Gain, A.K. Integrated spatial assessment of the water, energy and food dimensions of the sustainable development goals. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 1881–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. Governance of the water-energy-food security nexus: A multi-level coordination challenge. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 92, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B.; Luukkanen, J.; Silveira, S.; Kaivo-oja, J. Evaluating synergies and trade-offs among sustainable development goals (SDGs): Explorative analyses of development paths in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nhemachena, C.; Matchaya, G.; Nhemachena, C.R.; Karuaihe, S.; Muchara, B.; Nhlengethwa, S. Measuring baseline agriculture-related sustainable development goals index for southern Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avellán, T.; Ardakanian, R.; Perret, S.R.; Ragab, R.; Vlotman, W.; Zainal, H.; Im, S.; Gany, H.A. Considering resources beyond water: Irrigation and drainage management in the context of the water-energy-food nexus. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 67, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yillia, P.T. Water-energy-food nexus: Framing the opportunities, challenges and synergies for implementing the SDGs. Österreichische Wasser-und Abfallwirtschaft 2016, 68, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, G. Managing the food, water, and energy nexus for achieving the sustainable development goals in South Asia. Environ. Dev. 2016, 18, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- My World 2030. Available online: https://myworld2030.org/ (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- Stafford-Smith, M.; Griggs, D.; Gaffney, O.; Ullah, F.; Reyers, B.; Kanie, N.; Stigson, B.; Shrivastava, P.; Leach, M.; O’Connell, D. Integration: The key to implementing the sustainable development goals. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; Filho, W.L.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; de Mattos ascimento, D.L.; Ávila, L.V. A literature-based review on potentials and constraints in the implementation of the sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, R. Stakeholder Politics: Social Capital, Sustainable Development, and the Corporation; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780804763035. [Google Scholar]

- Katsoulakos, T.; Katsoulacos, Y. Strategic management, corporate responsibility and stakeholder management integrating corporate responsibility principles and stakeholder approaches into mainstream strategy: A stakeholder-oriented and integrative strategic management framework. Corp. Gov. 2007, 7, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| SDG | Relevant Keywords |

|---|---|

| 1. No poverty | poverty; *poor |

| 2. Zero hunger | hung*; food; agricult*; *nutriti*; “food energy” |

| 3. Good health and well-being | health*; mortality; death*; disease*; illness* |

| medicine*; vaccine*; “world health organization”; WHO | |

| 4. Quality education | educat*; learn*; school*; train*; knowledge; skill*; teach* |

| 5. Gender equality | “gender equality”; wom?n; girl*; femal*; feminis*; marriage; unpaid |

| 6. Clean water and sanitation | *water*; hydro*; aqua*; sanitation*; hygien* |

| 7. Affordable and clean energy | *energy; *fuel; electri*; biomass; *power |

| 8. Decent work and economic growth | “decent work”; “decent job”; *employ*; worker*; labour; labor; *econom*; “economic growth”; |

| “financial institution*”; “financial perform*”; “corporate social responsibility”; CSR; business | |

| 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure | Infrastructure; industr*; innovation; research*; internet; technology |

| “Information and communications technology”; ICT | |

| 10. Reduced inequalities | *equal*; inclus*; “protect* polic*”; “developing countr*”; “least developed countr*”; |

| “low?income countr*”; mobility; migra*; “world trade organization”; WTO | |

| 11. Sustainable cities and communities | city; cities; urban*; settlement*; housing; slum*; transport*; heritage; “public space*”; building*; “disaster risk management”; “air quality” |

| 12. Responsible consumption and production | consumption; consumer; production; product*; waste*; chemi*; reuse; recycle*; |

| “corporate social responsibility”; CSR; subsid*; “green economy”; “circular economy”; | |

| “low-carbon economy”; “green product”; “green growth”; “clean growth”; “environmental tax*” | |

| 13. Climate action | climat* |

| 14. Life below water | ocean*; mari*; sea*; coast*; *fish*; “life ? water” |

| 15. Life on land | *land*; ecosystem*; *forest*; terrestrial; biodiversity; “biological diversity”; desertification |

| 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions | peace*; violen*; war; just*; institution*; law*; crim*; *legal*; legislat*; act* |

| 17. Partnerships for the goals | global*; world; internation*; cooperat*; partnership*; trade; export |

| F | SDG 1 | SDG 2 | SDG 3 | SDG 4 | SDG 5 | SDG 6 | SDG 7 | SDG 8 | SDG 9 | SDG 10 | SDG 11 | SDG 12 | SDG 13 | SDG 14 | SDG 15 | SDG 16 | SDG 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 1 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| — | |||||||||||||||||

| SDG 2 | 121 | — | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| SDG 3 | 143 | 127 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 6 | — | |||||||||||||||

| SDG 4 | 116 | 109 | 152 | — | |||||||||||||

| 3 | 1 | 3 | — | ||||||||||||||

| SDG 5 | 104 | 91 | 124 | 107 | — | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | — | |||||||||||||

| SDG 6 | 107 | 124 | 136 | 104 | 93 | — | |||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | — | ||||||||||||

| SDG 7 | 104 | 118 | 107 | 96 | 87 | 125 | — | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | — | |||||||||||

| SDG 8 | 126 | 129 | 142 | 130 | 109 | 117 | 110 | — | |||||||||

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | — | ||||||||||

| SDG 9 | 103 | 116 | 113 | 115 | 88 | 110 | 112 | 125 | — | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | — | |||||||||

| SDG 10 | 127 | 107 | 160 | 110 | 112 | 109 | 99 | 127 | 106 | — | |||||||

| 7 | 0 | 14 | 7 | 39 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | — | ||||||||

| SDG 11 | 101 | 108 | 112 | 98 | 89 | 115 | 99 | 112 | 112 | 102 | — | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6 | — | |||||||

| SDG 12 | 94 | 111 | 107 | 97 | 87 | 104 | 108 | 118 | 118 | 93 | 99 | — | |||||

| 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | — | ||||||

| SDG 13 | 99 | 118 | 112 | 99 | 89 | 112 | 116 | 109 | 106 | 103 | 111 | 105 | — | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | — | |||||

| SDG 14 | 94 | 95 | 97 | 89 | 83 | 95 | 94 | 98 | 92 | 90 | 90 | 91 | 98 | — | |||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | — | ||||

| SDG 15 | 106 | 127 | 110 | 97 | 85 | 121 | 114 | 121 | 110 | 98 | 102 | 110 | 130 | 117 | — | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | — | |||

| SDG 16 | 107 | 98 | 132 | 113 | 103 | 99 | 96 | 114 | 97 | 125 | 95 | 91 | 101 | 90 | 100 | — | |

| 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | ||

| SDG 17 | 95 | 92 | 126 | 106 | 85 | 94 | 89 | 106 | 96 | 112 | 88 | 91 | 94 | 81 | 90 | 113 | — |

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | — | |

| A | 1747 | 1791 | 2000 | 1738 | 1536 | 1765 | 1674 | 1893 | 1719 | 1780 | 1633 | 1624 | 1702 | 1494 | 1738 | 1674 | 1558 |

| M | 21 | 17 | 53 | 22 | 51 | 19 | 16 | 20 | 15 | 95 | 42 | 34 | 21 | 17 | 19 | 28 | 42 |

| Rank | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic publications | SDG 3 | SDG 8 | SDG 10 | SDG 2 | SDG 6 | SDG 1 | SDG 15 | SDG 4 | SDG 9 | SDG 13 |

| Degree Centrality | 0.781 | 0.739 | 0.695 | 0.700 | 0.689 | 0.682 | 0.679 | 0.679 | 0.671 | 0.665 |

| Media | SDG 10 | SDG 3 | SDG 5 | SDG 11 | SDG 17 | SDG 12 | SDG 16 | SDG 4 | SDG 1 | SDG 13 |

| Degree Centrality | 0.152 | 0.085 | 0.082 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.054 | 0.045 | 0.035 | 0.034 | 0.034 |

| SDG# | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | Total Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combination | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2, 6, 7 | * | * | * | 14 | |||||||||||||||

| 3, 10, 16 | * | * | * | 14 | |||||||||||||||

| 1, 3, 10 | * | * | * | 13 | |||||||||||||||

| 3, 4, 10 | * | * | * | 13 | |||||||||||||||

| 1, 3, 4 | * | * | * | 13 | |||||||||||||||

| 3, 4, 8 | * | * | * | 12 | |||||||||||||||

| 3, 10, 17 | * | * | * | 11 | |||||||||||||||

| 2, 13, 15 | * | * | * | 11 | |||||||||||||||

| 3, 5, 10 | * | * | * | 11 | |||||||||||||||

| 1, 2, 3 | * | * | * | 10 | |||||||||||||||

| # of inclusion | 3 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ID | Year | Author | Title | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2018 | Albrecht et al. | The water-energy-food nexus: A systematic review of methods for nexus assessment [18] | Environmental Research Letters |

| 2 | Avellán et al. | Considering resources beyond water: Irrigation and drainage management in the context of the Water-Energy-Food nexus. [72] | Irrigation and Drainage | |

| 3 | Mainali et al. | Evaluating synergies and trade-offs among sustainable development goals (SDGs): Explorative analyses of development paths in south Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa [70] | Sustainability (Switzerland) | |

| 4 | Nhamo et al. | The water-energy-food nexus: Climate risks and opportunities in southern Africa. [16] | Water (Switzerland) | |

| 5 | Nhemachena et al. | Measuring baseline agriculture-related sustainable development goals index for southern Africa. [71] | Sustainability (Switzerland) | |

| 6 | 2017 | Giupponi & Gain | Integrated spatial assessment of the water, energy and food dimensions of the sustainable development goals. [68] | Regional Environmental Change |

| 7 | Liu et al. | Challenges in operationalizing the water–energy–food nexus. [19] | Hydrological Sciences Journal | |

| 8 | Pahl-Wostl | Governance of the water-energy-food security nexus: A multi-level coordination challenge. [69] | Environmental Science and Policy | |

| 9 | 2016 | Rasul | Managing the food, water, and energy nexus for achieving sustainable development goals in South Asia. [74] | Environmental Development |

| 10 | Yillia | Water-energy-food nexus: Framing the opportunities, challenges and synergies for implementing the SDGs. [73] | Osterreichische Wasser-Und Abfallwirtschaft |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeh, S.-C.; Chiou, H.-J.; Wu, A.-W.; Lee, H.-C.; Wu, H.C. Diverged Preferences towards Sustainable Development Goals? A Comparison between Academia and the Communication Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4577. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16224577

Yeh S-C, Chiou H-J, Wu A-W, Lee H-C, Wu HC. Diverged Preferences towards Sustainable Development Goals? A Comparison between Academia and the Communication Industry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(22):4577. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16224577

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeh, Shin-Cheng, Haw-Jeng Chiou, Ai-Wei Wu, Ho-Ching Lee, and Homer C. Wu. 2019. "Diverged Preferences towards Sustainable Development Goals? A Comparison between Academia and the Communication Industry" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 22: 4577. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph16224577