Social and Structural Determinants of Household Support for ART Adherence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Process

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening Process

2.4. Data Extraction, Assessment of Study Quality and Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Definitions, Concepts and Measurement

3.3.1. Definitions, Concepts and Measurement

3.3.2. Social and Structural Determinants Affecting Household and Family Member Support for ART Adherence

Gender

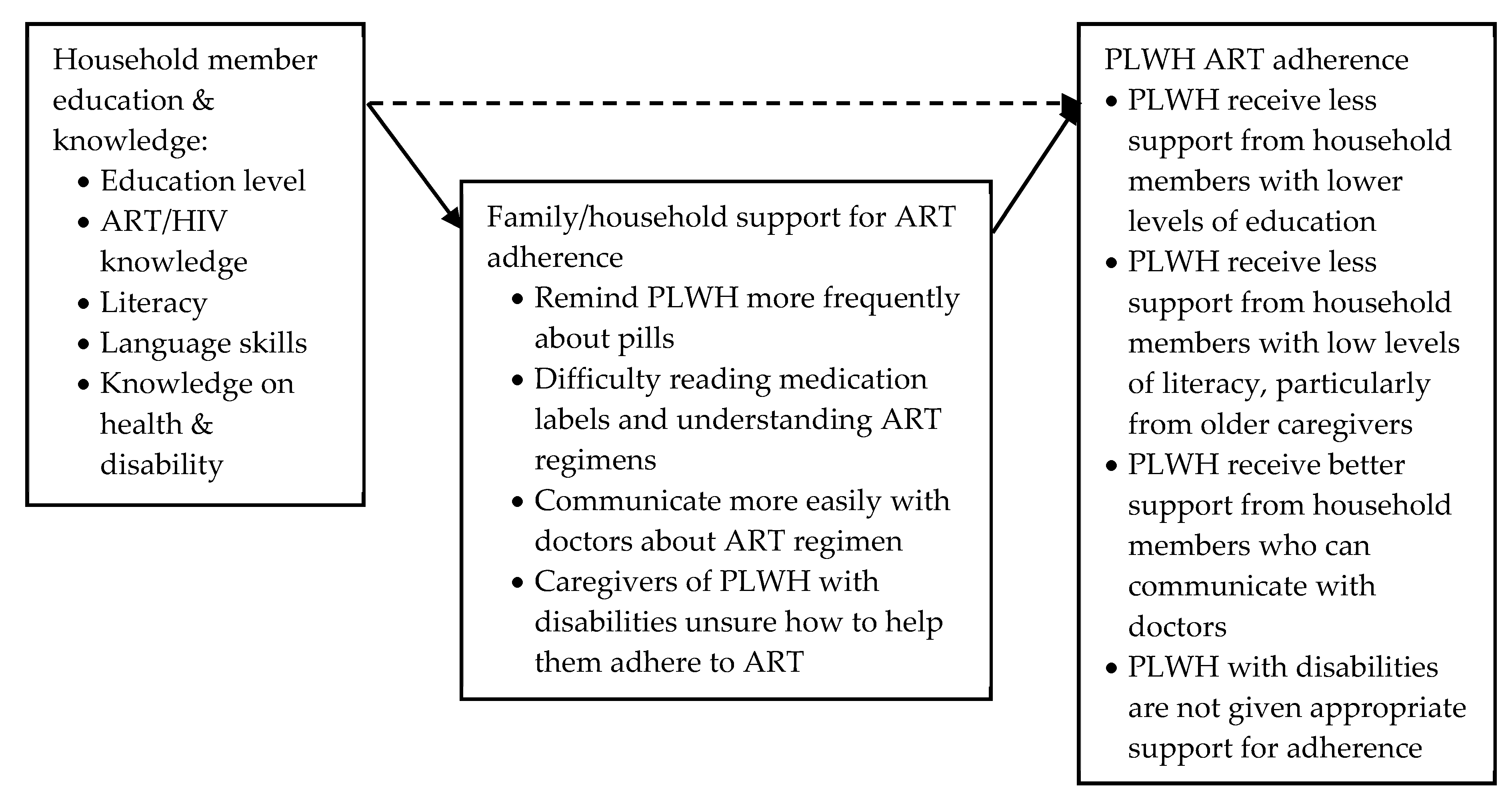

Education: Literacy, Language Skills and Health Knowledge

Religious and Cultural Health Beliefs

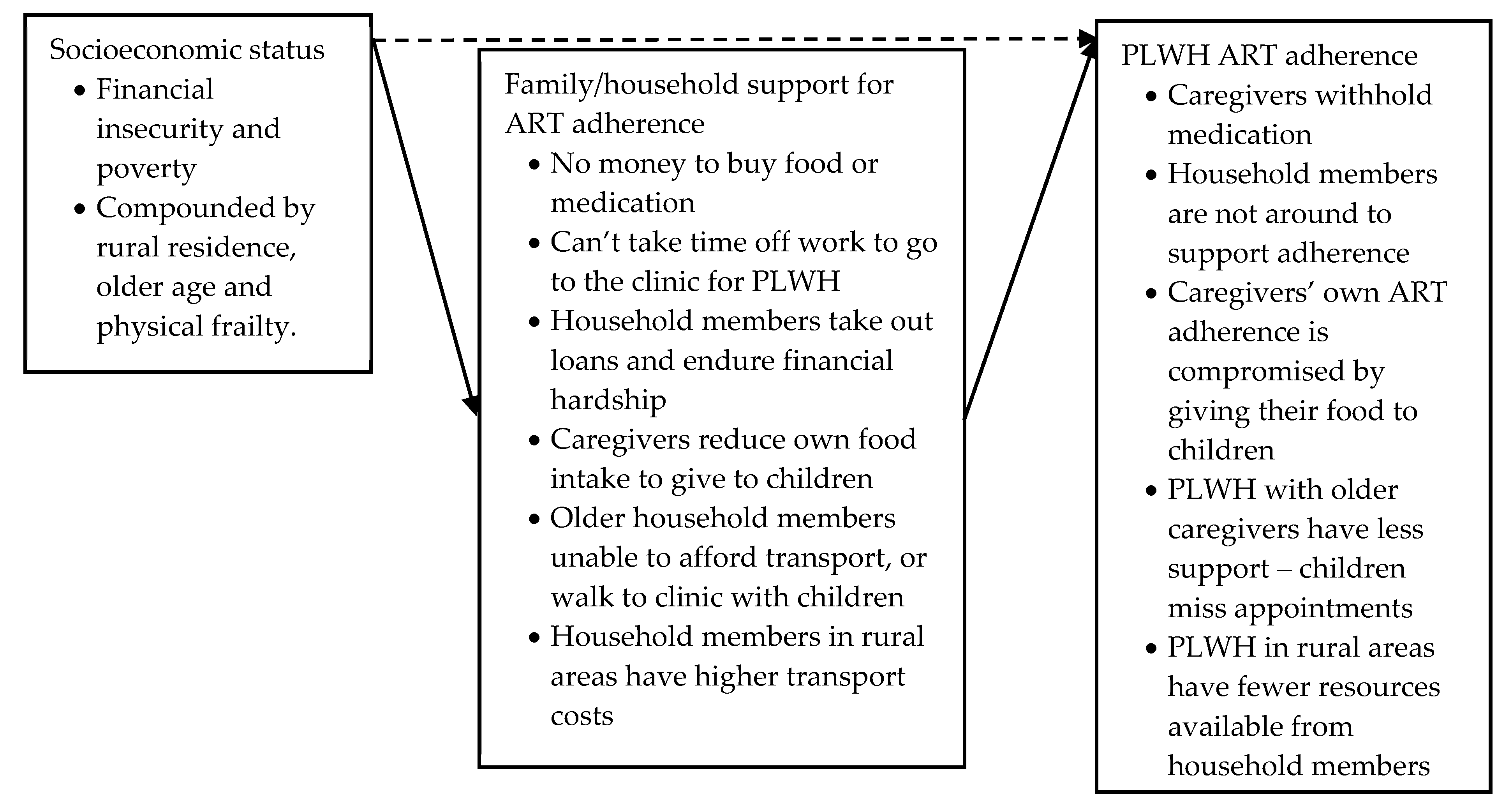

Socioeconomic Status: Poverty

Stigma: Secrecy, Disclosure and Access to Support

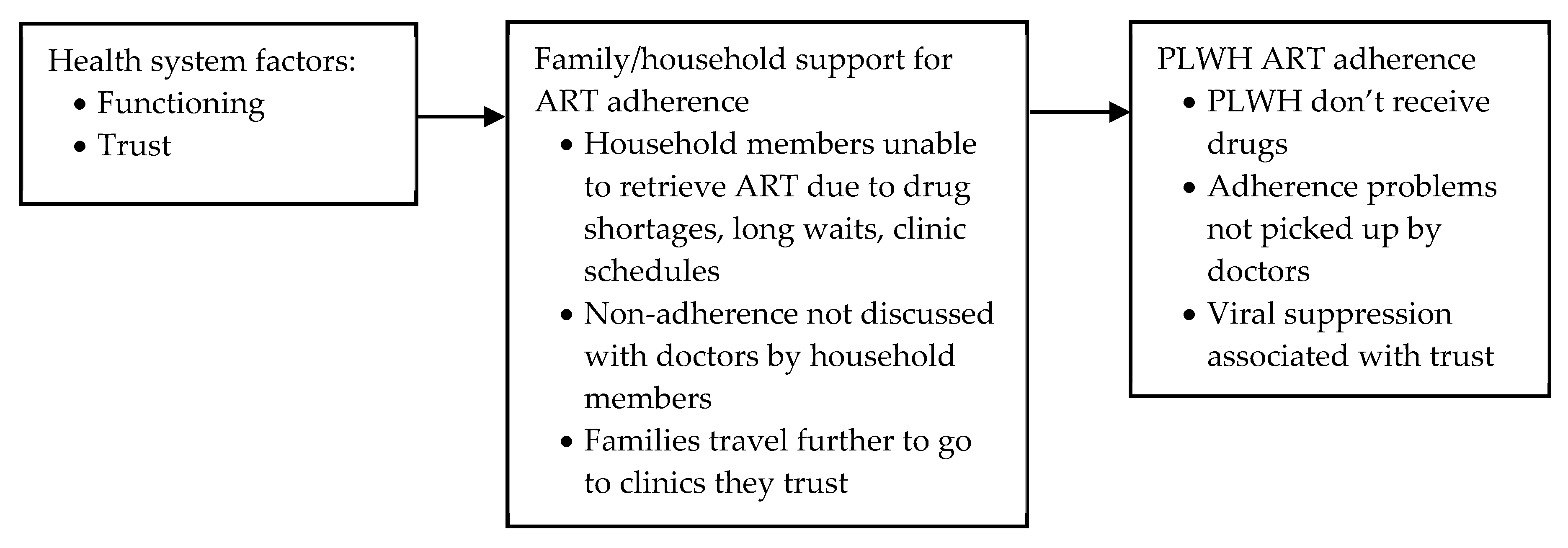

Health System Factors: Trust and Functioning

3.3.3. Caring for PLWH and Caring for the Carers

4. Discussion

Future Research

- (1)

- The majority of the studies reviewed focused on children and adolescents; further research on the social and structural determinants of household support for adherence among adults is needed to inform policy and intervention development.

- (2)

- Important gaps in knowledge such as how disability and sexual orientation stigma affect support for ART adherence.

- (3)

- The relationship between support given to household members, and the support they give to PLWH for adherence.

- (4)

- A more nuanced approach is warranted in the analysis of caregiver education and socioeconomic status, the resulting impact on support, and how this affects ART adherence. Researchers should maintain awareness, for example, of how different measures of socioeconomic status may result in considerably different classifications of household wealth [108] and therefore lead to different conclusions on the relationship between poverty, support and adherence.

- (5)

- The particular impact of gender, and religious and cultural health beliefs, on both household members and PLWH, and how this affects support for ART adherence.

- (6)

- How social and structural determinants intersect, in order to identify particularly vulnerable groups.

- (7)

- The effect of household support on ART adherence over time, and the impact of caregiver education, socioeconomic status, gender and decision-making power, which would better capture the changing influences on household support. Studies using path models could enable researchers to identify relationships between social determinants, household support, and ART adherence outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Margaret Chan, D.-G. Ten Years. In Public Health 2007–2017; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, S.; Egger, M.; Müller, M.; Zwahlen, M.; Low, N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2009, 23, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.S.; Chen, Y.Q.; McCauley, M.; Gamble, T.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; Kumarasamy, N.; Hakim, J.G.; Kumwenda, J.; Grinsztejn, B.; Pilotto, J.H.; et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Taylor, G. Rolling out HIV antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: 2003–2017. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2018, 44, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Treat All People Living with HIV, Offer Antiretrovirals as Additional Prevention Choice for People at “Substantial” Risk. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/hiv-treat-all-recommendation/en/ (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Vardell, E. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2020, 39, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNAIDS. FACT SHEET–WORLD AIDS DAY 2019; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Juneja, S.; Vitoria, M.; Habiyambere, V.; Nguimfack, B.D.; Doherty, M.; Low-Beer, D. Projected Uptake of New Antiretroviral (ARV) Medicines in Adults in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Forecast Analysis 2015-2025. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussari, O.; Subtil, F.; Genolini, C.; Bastard, M.; Iwaz, J.; Fonton, N.H.; Etard, J.-F.; Ecochard, R. Impact of variability in adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy on the immunovirological response and mortality. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, R.K.; Gregson, J.; Parkin, N.; Haile-Selassie, H.; Tanuri, A.; Forero, L.A.; Kaleebu, P.; Watera, C.; Aghokeng, A.; Mutenda, N.; et al. HIV-1 drug resistance before initiation or re-initiation of first-line antiretroviral therapy in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogg, R.S.; Heath, K.; Bangsberg, D.; Yip, B.; Press, N.; O’Shaughnessy, M.V.; Montaner, J.S.G. Intermittent use of triple-combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up. AIDS 2002, 16, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mannheimer, S.; Friedland, G.; Matts, J.; Child, C.; Chesney, M. The Consistency of Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Predicts Biologic Outcomes for Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Infected Persons in Clinical Trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsberg, D.R.; Perry, S.; Charlebois, E.D.; Clark, R.A.; Roberston, M.; Zolopa, A.R.; Moss, A. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS 2001, 15, 1181–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D.L.; Swindells, S.; Mohr, J.; Brester, M.; Vergis, E.N.; Squier, C.; Wagener, M.M.; Singh, N. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberer, J.E.; Sabin, L.; Amico, R.K.; Orrell, C.; Galárraga, O.; Tsai, A.C.; Vreeman, R.C.; Wilson, I.; Sam-Agudu, N.A.; Blaschke, T.F.; et al. Improving antiretroviral therapy adherence in resource-limited settings at scale: A discussion of interventions and recommendations. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgeway, K.; Dulli, L.; Murray, K.R.; Silverstein, H.; Santo, L.D.; Olsen, P.; De Mora, D.D.; McCarraher, D.R. Interventions to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simoni, J.M.; Amico, R.K.; Smith, L.; Nelson, K.M. Antiretroviral Adherence Interventions: Translating Research Findings to the Real World Clinic. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010, 7, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simoni, J.M.; Pearson, C.R.; Pantalone, D.W.; Marks, G.; Crepaz, N. Efficacy of Interventions in Improving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence and HIV-1 RNA Viral Load. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006, 43, S23–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masquillier, C.; Wouters, E.; Mortelmans, D.; Van Wyk, B. On the Road to HIV/AIDS Competence in the Household: Building a Health-Enabling Environment for People Living with HIV/AIDS. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 3264–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masquillier, C.; Wouters, E.; Mortelmans, D.; Van Wyk, B.; Hausler, H.; Van Damme, W. HIV/AIDS Competent Households: Interaction between a Health-Enabling Environment and Community-Based Treatment Adherence Support for People Living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, C.; Jana, S.; Lambert, H. What makes a structural intervention? Reducing vulnerability to HIV in community settings, with particular reference to sex work. Glob. Public Health 2010, 5, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.R.; Parkhurst, J.O.; Ogden, J.A.; Aggleton, P.; Mahal, A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet 2008, 372, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, S.; Logie, C.H.; Grosso, A.; Wirtz, A.L.; Melbye, K. Modified social ecological model: A tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaufman, M.R.; Cornish, F.; Zimmerman, R.S.; Johnson, B.T. Health Behavior Change Models for HIV Prevention and AIDS Care. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 66, S250–S258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wouters, E.; Masquillier, C.; Ponnet, K.; Booysen, F. A peer adherence support intervention to improve the antiretroviral treatment outcomes of HIV patients in South Africa: The moderating role of family dynamics. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 113, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukumbang, F.C.; Knight, L.; Masquillier, C.; Delport, A.; Sematlane, N.; Dube, L.T.; Lembani, M.; Wouters, E. Household-focused interventions to enhance the treatment and management of HIV in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wouters, E. Life with HIV as a chronic illness: A theoretical and methodological framework for antiretroviral treatment studies in resource-limited settings. Soc. Theory Health 2012, 10, 368–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, C.A.; Israel, B.A. Social networks and social support. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sumartojo, E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: Concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS 2000, 14, S3–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweat, M.D.; Denison, J.A. Reducing HIV incidence in developing countries with structural and environmental interventions. AIDS 1995, 9, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, J.; Parkhurst, J.O.; Cáceres, C.F. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Glob. Public Health 2011, 6, S293–S309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettifor, A.; MacPhail, C.; Nguyen, N.; Rosenberg, M. Can money prevent the spread of HIV? A review of cash payments for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16, 1729–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, S.L. Who is epidemiologically fathomable in the HIV/AIDS epidemic? Gender, sexuality, and intersectionality in public health. Cult. Health Sex. 2006, 7, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammon, N.; Mason, S.; Corkery, J.M. Factors impacting antiretroviral therapy adherence among human immunodeficiency virus–positive adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Public Health 2018, 157, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azmach, N.N.; Hamza, T.A.; Husen, A.A. Socioeconomic and Demographic Statuses as Determinants of Adherence to Antiretroviral Treatment in HIV Infected Patients: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Curr. HIV Res. 2019, 17, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Zarkadoulia, E.A.; Pliatsika, P.A.; Panos, G. Socioeconomic status (SES) as a determinant of adherence to treatment in HIV infected patients: A systematic review of the literature. Retrovirology 2008, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hudelson, C.; Cluver, L.D. Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, E.J.; Nachega, J.B.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Singh, S.; Rachlis, B.; Wu, P.; Wilson, K.; Buchan, I.; Gill, C.J.; Cooper, C. Adherence to HAART: A systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, A.A.; Biadgilign, S. Determinants of Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Infected Patients in Africa. AIDS Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 574656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reisner, S.; Mimiaga, M.J.; Skeer, M.; Perkovich, B.; Johnson, C.V.; Safren, S.A. A review of HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Top. HIV Med. Publ. Int. AIDS Soc. USA 2009, 17, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni, J.M.; Montgomery, A.; Martin, E.; New, M.; Demas, P.A.; Rana, S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infection: A qualitative systematic review with recommendations for research and clinical management. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e1371–e1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vreeman, R.; Wiehe, S.; Pearce, E.C.; Nyandiko, W.M. A Systematic Review of Pediatric Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2008, 27, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.P.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Simkhada, P.; Randall, J.; Baxter, S.; Kirkpatrick, P.; Gc, V.S. Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Asian developing countries: A systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 17, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woke, F. Socio-demographic Determinants of Anti-Retroviral Therapy Adherence in South Africa: A Systematic Review from 2009–2014. WebMed Cent. AIDS 2015, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, A.; McKenna, S.A.; Comfort, M.L.; Darbes, L.A.; Tan, J.Y.; Mkandawire, J. Marital infidelity, food insecurity, and couple instability: A web of challenges for dyadic coordination around antiretroviral therapy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 214, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheurer, D.; Choudhry, N.; Swanton, K.A.; Matlin, O.; Shrank, W. Association between different types of social support and medication adherence. Am. J. Manag. Care 2012, 18, 461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Berman, S.M.; Swindells, S.; Justis, J.C.; Mohr, J.A.; Squier, C.; Wagener, M.M. Adherence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Infected Patients to Antiretroviral Therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999, 29, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, U.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niehof, A. Conceptualizing the household as an object of study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, W. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2019. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Spencer, L.; Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Dillon, L. Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence; National Centre for Social Research: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies Systematic Review. 2013. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A.; Oakley, A.; Oliver, S.; Sutcliffe, K.; Rees, R.; Brunton, G.; Kavanagh, J. Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews. BMJ 2004, 328, 1010–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shepperd, S.; Lewin, S.; Straus, S.; Clarke, M.; Eccles, M.P.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Wong, G.; Sheikh, A. Can We Systematically Review Studies That Evaluate Complex Interventions? PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hare, G. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA; London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwanjee, A.; Govender, K.; Reardon, C.; Johnstone, L.; George, G.; Gordon, S. Gendered constructions of the impact of HIV and AIDS in the context of the HIV-positive seroconcordant heterosexual relationship. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikaako-Kajura, W.; Luyirika, E.; Purcell, D.; Downing, J.; Kaharuza, F.; Mermin, J.; Malamba, S.; Bunnell, R. Disclosure of HIV Status and Adherence to Daily Drug Regimens Among HIV-infected Children in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busza, J.; Dauya, E.; Bandason, T.; Mujuru, H.; Ferrand, R.A. I don’t want financial support but verbal support. How do caregivers manage children’s access to and retention in HIV care in urban Zimbabwe? J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2014, 17, 18839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, A.; Leddy, A.; Johnson, M.; Ngubane, T.; Van Rooyen, H.; Darbes, L. “I told her this is your life”: Relationship Dynamics, Partner Support, and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among South African Couples. Cult. Health Sex. 2017, 19, 1239–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Demmer, C. Experiences of families caring for an HIV-infected child in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: An exploratory study. AIDS Care 2011, 23, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fetzer, B.C.; Mupenda, B.; Lusiama, J.; Kitetele, F.; Golin, C.; Behets, F. Barriers to and Facilitators of Adherence to Pediatric Antiretroviral Therapy in a Sub-Saharan Setting: Insights from a Qualitative Study. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2011, 25, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohli, R.; Purohit, V.; Karve, L.; Bhalerao, V.; Karvande, S.; Rangan, S.; Reddy, S.; Paranjape, R.; Sahay, S. Caring for Caregivers of People Living with HIV in the Family: A Response to the HIV Pandemic from Two Urban Slum Communities in Pune, India. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mafune, R.V.; Lebese, R.T.; Nemathaga, L.H. Challenges faced by caregivers of children on antiretroviral therapy at Mutale Municipality selected healthcare facilities, Vhembe District, Limpopo Province. Curationis 2017, 40, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez, R.M. The Stigma and Discrimination in the Processes of Lack of Adherence to Antiretroviral Treatment. An Analysis within the Context of Family, Community and Health Care Providers in Guayaquil (Ecuador). Aposta-Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2018, 78, 33–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nasuuna, E.; Kigozi, J.; Muwanguzi, P.A.; Babirye, J.; Kiwala, L.; Muganzi, A.; Sewankambo, N.K.; Nakanjako, D. Challenges faced by caregivers of virally non-suppressed children on the intensive adherence counselling program in Uganda: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nestadt, D.F.; Lakhonpon, S.; Pardo, G.; Saisaengjan, C.; Gopalan, P.; Bunupuradah, T.; McKay, M.M.; Ananworanich, J.; Mellins, C.A. A qualitative exploration of psychosocial challenges of perinatally HIV-infected adolescents and families in Bangkok, Thailand. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2017, 13, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, P.K.; Kiwanuka, J.P.; Ware, N.C.; Tsai, A.C.; Haberer, J. Explaining antiretroviral therapy adherence success among HIV-infected children in rural Uganda: A qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2015, 19, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paranthaman, K.; Kumarasamy, N.; Bella, D.; Webster, P. Factors influencing adherence to anti-retroviral treatment in children with human immunodeficiency virus in South India—A qualitative study. AIDS Care 2009, 21, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petersen, I.; Bhana, A.; Myeza, N.; Alicea, S.; John, S.; Holst, H.; McKay, M.; Mellins, C. Psychosocial challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. AIDS Care 2010, 22, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Punpanich, W.; Detels, R.; Gorbach, P.M.; Leowsrisook, P. Understanding the psychosocial needs of HIV-infected children and families: A qualitative study. J. Med Assoc. Thail. Chotmaihet Thangphaet 2008, 91, S76–S84. [Google Scholar]

- Purchase, S.; Cunningham, J.; Esser, M.; Skinner, N. Keeping kids in care: Virological failure in a paediatric antiretroviral clinic and suggestions for improving treatment outcomes. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2016, 15, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remien, R.H.; Mellins, C.A.; Robbins, R.N.; Kelsey, R.; Rowe, J.; Warne, P.; Chowdhury, J.; Lalkhen, N.; Hoppe, L.; Abrams, E.J.; et al. Masivukeni: Development of a multimedia based antiretroviral therapy adherence intervention for counselors and patients in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 1979–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, K.; Campbell, C.; Madanhire, C.; Skovdal, M.; Nyamukapa, C.; Gregson, S. In what ways do communities support optimal antiretroviral treatment in Zimbabwe? Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaibu, S. Caring for HIV-positive orphans in the context of HIV and AIDS: Perspectives of Botswana grandmothers. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2016, 11, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovdal, M.; Campbell, C.; Madanhire, C.; Nyamukapa, C.; Gregson, S. Challenges faced by elderly guardians in sustaining the adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 2011, 23, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovdal, M.; Campbell, C.; Nyamukapa, C.; Gregson, S. When masculinity interferes with women’s treatment of HIV infection: A qualitative study about adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2011, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vreeman, R.; Nyandiko, W.; Ayaya, S.O.; Walumbe, E.G.; Marrero, D.G.; Inui, T.S. Factors Sustaining Pediatric Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Western Kenya. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 1716–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, N.C.; Idoko, J.; Kaaya, S.; Biraro, I.A.; Wyatt, M.A.; Agbaji, O.; Chalamilla, G.; Bangsberg, D.R. Explaining Adherence Success in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Ethnographic Study. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yeap, A.D.; Hamilton, R.; Charalambous, S.; Dwadwa, T.; Churchyard, G.; Geissler, P.; Grant, A. Factors influencing uptake of HIV care and treatment among children in South Africa—A qualitative study of caregivers and clinic staff. AIDS Care 2010, 22, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.; Boulle, A.; Fakir, T.; Nuttall, J.; Eley, B. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in young children in Cape Town, South Africa, measured by medication return and caregiver self-report: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2008, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knodel, J.; Hak, S.; Khuon, C.; So, D.; McAndrew, J. Parents and family members in the era of ART: Evidence from Cambodia and Thailand. AIDS Care 2011, 23, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, A.; Bode, S.; Myer, L.; Stahl, J.; Von Steinbüchel, N. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral treatment and therapeutic success among children in South Africa. AIDS Care 2010, 23, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polisset, J.; Ametonou, F.; Arrive, E.; Aho, A.; Perez, F. Correlates of Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV-Infected Children in Lomé, Togo, West Africa. AIDS Behav. 2008, 13, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I.; Shiu, C.-S.; Starks, H.; Chen, W.-T.; Simoni, J.M.; Kim, H.-J.; Pearson, C.R.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, F. “You Must Take the Medications for You and for Me”: Family Caregivers Promoting HIV Medication Adherence in China. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2011, 25, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tran, C.; Pham, T.; Tran, K.; Nguyen, T.; Larsson, M. Caretakers’ barriers to pediatric antiretroviral therapy adherence in Vietnam—A qualitative and quantitative study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, R.; Namakhoma, I.; Tauzie, J.; Chiunguzeni, D.; Phiri, S.; Theobald, S. Supporting children to adhere to anti-retroviral therapy in urban Malawi: Multi method insights. BMC Pediatr. 2009, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, L.; Munir, K.; Kanabkaew, C.; Le Coeur, S. Factors influencing antiretroviral treatment suboptimal adherence among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuo, C.; Operario, D. Caring for AIDS-orphaned children: A systematic review of studies on caregivers. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2009, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, E.; Igonya, E.K. When families fail: Shifting expectations of care among people living with HIV in Nairobi, Kenya. Anthr. Med. 2014, 21, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hatcher, A.; Smout, E.M.; Turan, J.M.; Christofides, N.J.; Stoeckl, H. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women. AIDS 2015, 29, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arage, G.; Tessema, G.; Kassa, H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its associated factors among children at South Wollo Zone Hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Howe, L.D.; Galobardes, B.; Matijasevich, A.; Gordon, D.; Johnston, D.; Onwujekwe, O.; Patel, R.; Webb, E.; Lawlor, D.; Hargreaves, J.R. Measuring socio-economic position for epidemiological studies in low- and middle-income countries: A methods of measurement in epidemiology paper. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kendrick, H.M. Are religion and spirituality barriers or facilitators to treatment for HIV: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Care 2016, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, M. Economic strengthening for retention in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A review of the evidence. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vreeman, R.C.; Scanlon, M.L.; Tu, W.; Slaven, J.E.; McAteer, C.I.; Kerr, S.J.; Bunupuradah, T.; Chanthaburanum, S.; Technau, K.; Nyandiko, W.M. Validation of a self-report adherence measurement tool among a multinational cohort of children living with HIV in Kenya, South Africa and Thailand. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aderomilehin, O.; Hanciles-Amu, A.; Ozoya, O. Perspectives and Practice of HIV Disclosure to Children and Adolescents by Health-Care Providers and Caregivers in sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katz, I.; Ryu, A.E.; Onuegbu, A.G.; Psaros, C.; Weiser, S.D.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Tsai, A.C. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: Systematic review and meta-synthesis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijker, R.; Jiamsakul, A.; Kityo, C.; Kiertiburanakul, S.; Siwale, M.; Phanuphak, P.; Akanmu, S.; Chaiwarith, R.; Wit, F.W.; Sim, B.L.; et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia: A comparative analysis of two regional cohorts. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, S.A.; Cameron, C.; Hanass-Hancock, J.; Simwaba, P.; Solomon, P.; Bond, V.A.; Menon, A.; Richardson, E.; Stevens, M.; Zack, E. Perceptions of HIV-related health services in Zambia for people with disabilities who are HIV-positive. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2014, 17, 18806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanass-Hancock, J.; Myezwa, H.; Carpenter, B. Disability and Living with HIV: Baseline from a Cohort of People on Long Term ART in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arnold, E.A.; Rebchook, G.M.; Kegeles, S.M. ‘Triply cursed’: Racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young Black gay men. Cult. Health Sex. 2014, 16, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Micheni, M.; Secor, A.; Van Der Elst, E.M.; Kombo, B.; Operario, N.; Amico, K.R.; Sanders, E.J.; Simoni, J.M. HIV care engagement and ART adherence among Kenyan gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: A multi-level model informed by qualitative research. AIDS Care 2018, 30, S97–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quinn, K.; Dickson-Gomez, J.; Broaddus, M.; Kelly, J.A. “It’s Almost Like a Crab-in-a-Barrel Situation”: Stigma, Social Support, and Engagement in Care Among Black Men Living With HIV. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2018, 30, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conroy, A.A.; McKenna, S.A.; Ruark, A. Couple Interdependence Impacts Alcohol Use and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2018, 23, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczynski, N.L.; Haynes, R.B. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound prognostic studies in MEDLINE: An analytic survey. BMC Med. 2004, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howe, L.D.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Ploubidis, G.B.; De Stavola, B.; Huttly, S.R.A. Subjective measures of socio-economic position and the wealth index: A comparative analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2010, 26, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Web of Science (TS = topic = title + abstract + key words) Filter: 2003–2019 | #1 TS = (household* OR home* OR famil* OR couple* OR relationship* OR interpersonal) #2 TS = (adhere* OR complian*) #3 TS = (help OR support OR empower* OR care OR caring OR social support) #4 TS = (HIV OR ART OR ARV OR viral* OR CD4 OR pill count OR antiretroviral therapy OR antiretroviral treatment) #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 |

| Social/Structural Factor | Studies of Good Quality | Studies of Fair Quality | Studies of Poor Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 3 studies [46,61,78] | 6 studies [58,62,64,66,75,81] | 1 study [88] |

| Education: literacy, language and knowledge | 2 studies [82,84] | 8 studies [65,74,75,76,81,83,85,87] | 3 studies [77,86,89] |

| Religious & cultural health beliefs | 1 study [79] | 8 studies [62,63,66,68,76,80,81,82] | 2 studies [86,89] |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | 4 studies [46,61,79,82] | 16 studies [59,60,62,63,64,65,67,68,69,71,73,76,80,81,85,87] | 6 studies [70,72,77,86,88,89] |

| Stigma | 2 studies [79,84] | 17 studies [59,60,62,63,65,66,67,68,69,71,73,75,76,80,81,85,87] | 4 studies [70,72,86,88] |

| Health system factors | 2 studies [79,84] | 7 studies [60,67,73,80,81,85,87] | 2 studies [70,88] |

| Caring for the carers: mitigating social and structural barriers | 2 studies [79,84] | 11 studies [59,60,63,67,69,71,74,75,76,80,83] | 2 studies [70,77] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campbell, L.; Masquillier, C.; Thunnissen, E.; Ariyo, E.; Tabana, H.; Sematlane, N.; Delport, A.; Dube, L.T.; Knight, L.; Kasztan Flechner, T.; et al. Social and Structural Determinants of Household Support for ART Adherence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review . Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3808. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17113808

Campbell L, Masquillier C, Thunnissen E, Ariyo E, Tabana H, Sematlane N, Delport A, Dube LT, Knight L, Kasztan Flechner T, et al. Social and Structural Determinants of Household Support for ART Adherence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review . International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):3808. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17113808

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampbell, Linda, Caroline Masquillier, Estrelle Thunnissen, Esther Ariyo, Hanani Tabana, Neo Sematlane, Anton Delport, Lorraine Tanyaradzwa Dube, Lucia Knight, Tair Kasztan Flechner, and et al. 2020. "Social and Structural Determinants of Household Support for ART Adherence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review " International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 11: 3808. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17113808