Forest Volatile Organic Compounds and Their Effects on Human Health: A State-of-the-Art Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

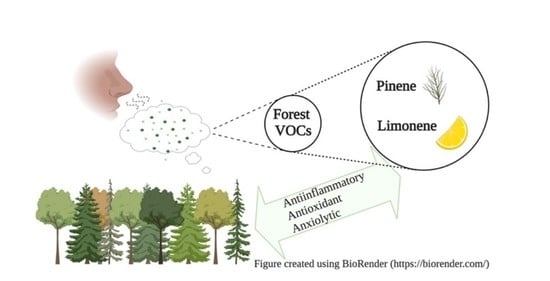

1.1. Forest Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): Background and Natural Functions

- Inducible forest VOCs (herbivore-induced plant volatiles; henceforth HIPVs) are compounds whose synthesis is increased or initiated de-novo after herbivore attacks but also after stimulation by abiotic stressors. They have some metabolic costs but they make the plant phenotypically plastic and herbivore adaptation more unlikely to occur [5].

1.2. Non-Tree-Derived Forest BVOCs

1.3. Research Aim

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Biochemistry of Forest VOCs

3.1.1. Isoprenoids

3.1.2. Oxylipins

3.1.3. Shikimate Pathway

3.2. A Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Forest VOC Emissions

3.3. BVOCs and Plant-Derived Essential Oils

- antimicrobial effects on antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains;

- antitussive, mucoactive, bronchodilation, and antispasmodic activities on the respiratory system;

- non-olfactory-mediated psychopharmacological effects on arousal, activation, memory loss, dementia, cognitive performance, anxiety, quality of life, quality of sleep;

- antioxidant effect;

- antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic activity;

- anti-nausea and spasmolytic effects on the intestine.

3.4. Evidence about the General Effects of Forest VOCs on Health

3.4.1. Immune System and Inflammation

3.4.2. Nervous System and Psychological Behavior

3.4.3. Endocrine System and Stress

3.5. Limonene

3.5.1. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

3.5.2. Antioxidant Activity

3.5.3. Antiproliferative Activity

3.5.4. Antinociceptive Activity

3.5.5. Other Pharmacological Activities

3.6. Pinenes

Pharmacological and Clinical Activities of Pinenes

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Individual Health

- the exact concentration of any BVOC in the forest air when exposure occurs;

- the duration of exposure;

- the intensity of physical activities performed in the green environment;

- specific modalities of biological sample collection, transport, and analysis;

- individual health-related characteristics, which can influence the uptake, metabolism, accumulation, and excretion of inhaled BVOCs;

- lifestyle habits, which can determine baseline blood levels of compounds like limonene and pinene absorbed from food, medicines, and perfumes [58].

| Molecule | Effects | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-Limonene | Anti-inflammatory | It inhibits the synthesis or release of pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, NO, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-5, IL-13, TGF-β), enzymes (5-LOX, COX-2, iNOS), transcription factors (NF-κB), and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase family members (p38, JNK, ERK). | [4,70,71,124] |

| Antioxidant | It inhibits caspase-3/caspase-9 activation, increases the activities of cell antioxidant enzymes (catalase, peroxidase) and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio. | [4,70,123] | |

| Antiproliferative | It induces phase II carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes, inhibits prenyl-transferase activity, increases cell autophagy (via MAP1LC3B, mitochondrial death pathway, the PI3k/Akt pathway, and caspase-3 and -9 activity) and differentiation, reduces cyclin-D1 and increases TGF-β signaling, decreases tumor-induced immunosuppression, reduces circulating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and blocks the receptor VEGF-R1, increases DNA damage repair and PARP cleavage. It modulates the expression of the chemotactic protein MCP-1 and of the proteolytic enzymes MMP-2, MMP-9. | [4,17,24,110,111,121,124,128,129] | |

| Antinociceptive | Bimodal activity: topically applied, it seems capable of eliciting pain, via interaction with TRPA1 ion channels, while in other modes of administration, it has shown antinociceptive effects in different experimental models. | [24,90,116,127,133,136,137] | |

| Anxiolytic | It shows some degree of efficacy in mice and rat models. | [90,127,135] | |

| Antidepressant | It shows some degree of efficacy in mice and rat models. | [132,133,134] | |

| α-Pinene | Anxiolytic, sedative | In several animal models, it enhances sleep by acting as a positive modulator for GABA-A-BZD receptors, prolonging GABAergic inhibitory signaling. | [91,155,157,158,159,160,161] |

| Anti-inflammatory | It modulates NF-κB and IκBα, ERK, JNK, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS (and NO secretions), MMP-1, MMP-13, COX-2. | [146,152,153,155,156] | |

| Antioxidant | It reduces ROS production, caspase-3 activity, modulates superoxide dismutase, catalase, peroxidase activity, NO and IL-6 secretions. | [146,155,168] | |

| Antiproliferative | It acts on efflux pumps responsible for multidrug-resistant tumors and on cell cycle arrest via the cyclin-B protein. | [147,148] | |

| Analgesic | It shows some degree of efficacy in animal models. | [156,162,163] | |

| β-Pinene | Anxiolytic, antidepressant | It binds to the GABA-A receptor, prolonging GABAergic inhibitory signaling. It showed efficacy in animal models. | [91,94,95,96,97] |

| Anti-inflammatory | It modulates NF-κB and IκBα. | [146] | |

| Antioxidant | It reduces ROS production, caspase-3 activity, MMP and NO activities. | [77,78,79,80,146] | |

| Antiproliferative | It acts on efflux pumps responsible for multidrug-resistant tumors and on cell cycle arrest via the cyclin-B protein. | [147,148] | |

| β-Myrcene | Anti-inflammatory | It modulates MAP kinases such as JNK, p38, and it inhibits the synthesis and release of PGE-2. | [70,71,169] |

| Antiproliferative | It blocks hepatic carcinogenesis caused by aflatoxin. | [170] | |

| Analgesic | It is analgesic in mice, and its action is blocked by naloxone, perhaps via the α-2 adrenoreceptor. | [171] | |

| Sedative, myorelaxant | It is a muscle relaxant in mice, and it potentiates barbiturate sleep time at high doses. | [88] | |

| Gastroprotective | It contributes to the integrity of the gastric mucosa, decreasing ulcerative lesions, attenuating lipid peroxidative damage, and preventing depletion of GSH, GR, and GPx. | [172] | |

| Camphene | Metabolism | As a food supplement, it reduces animal models’ body weight and increases adiponectin levels and receptor mRNA expression in the liver. | [173] |

| Antiproliferative | It induces apoptosis in cancer cell lines (B16F10-Nex2 melanoma), chromatin condensation, cell shrinkage, apoptotic body formation, fragmentation of nucleus, and caspase-3 activation. | [174] | |

| Antioxidant | It prevents AAPH-induced lipoperoxidation and inhibits the superoxide radical. | [175] | |

| Antinociceptive | Weak effects on acetic acid-induced writhing in mice models. | [175] | |

| Antihyperlipidemic | It reduces total and LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides in hyperlipidemic rats and in HepG2 cells, not by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase but by increasing apolipoprotein AI expression, possibly via SREBP-1 upregulation and MTP inhibition. | [176] |

4.2. Implications for Preventive Medicine and Public Health

4.3. Forest VOCs and Natural Landscape Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Went, F.W. Blue hazes in the atmosphere. Nature 1960, 187, 641–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, R.A.; Went, F.W. Volatile organic material of plant origin in the atmosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1965, 53, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guenther, A.B.; Jiang, X.; Heald, C.L.; Sakulyanontvittaya, T.; Duhl, T.; Emmons, L.K.; Wang, X. The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): An extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012, 5, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, T.; Song, B.; Cho, K.S.; Lee, I.-S. Therapeutic Potential of Volatile Terpenes and Terpenoids from Forests for Inflammatory Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Niinemets, Ü.; Monson, R.K. Biology, Controls and Models of Tree Volatile Organic Compound Emissions; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 9789400766051. [Google Scholar]

- Dyakov, Y.T.; Dzhavakhiya, V.G.; Korpela, T. Comprehensive and Molecular Phytopathology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 9780444521323. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, M. Phytoncide—Its Properties and Applications in Practical Use. In Gas Biology Research in Clinical Practice; Karger Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Laothawornkitkul, J.; Taylor, J.E.; Paul, N.D.; Hewitt, C.N. Biogenic volatile organic compounds in the Earth system. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- War, A.R.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ahmad, T.; Buhroo, A.A.; Hussain, B.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Sharma, H.C. Mechanisms of plant defense against insect herbivores. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1306–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Materić, D.; Bruhn, D.; Turner, C.; Morgan, G.; Mason, N.; Gauci, V. Methods in plant foliar volatile organic compounds research. Appl. Plant Sci. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonwani, S.; Saxena, P.; Kulshrestha, U. Role of Global Warming and Plant Signaling in BVOC Emissions. In Plant Responses to Air Pollution; Kulshrestha, U., Saxena, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 45–57. ISBN 9789811012013. [Google Scholar]

- Loreto, F.; Schnitzler, J.-P. Abiotic stresses and induced BVOCs. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Pichersky, E.; Gershenzon, J. Biochemistry of plant volatiles. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vivaldo, G.; Masi, E.; Taiti, C.; Caldarelli, G.; Mancuso, S. The network of plants volatile organic compounds. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Memari, H.R.; Pazouki, L.; Niinemets, Ü. The Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Volatile Messengers in Trees. In Biology, Controls and Models of Tree Volatile Organic Compound Emissions; Niinemets, Ü., Monson, R.K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 47–93. ISBN 9789400766068. [Google Scholar]

- Peñuelas, J.; Llusià, J. BVOCs: Plant defense against climate warming? Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, M.E.; Gertsch, J.; Appendino, G. Plant volatiles: Production, function and pharmacology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1359–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Sureda, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Daglia, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Valussi, M.; Tundis, R.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; et al. Biological Activities of Essential Oils: From Plant Chemoecology to Traditional Healing Systems. Molecules 2017, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimpraga, M.; Ghimire, R.P.; Van Der Straeten, D.; Blande, J.D.; Kasurinen, A.; Sorvari, J.; Holopainen, T.; Adriaenssens, S.; Holopainen, J.K.; Kivimäenpää, M. Unravelling the functions of biogenic volatiles in boreal and temperate forest ecosystems. Eur. J. For. Res. 2019, 138, 763–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ditengou, F.A.; Müller, A.; Rosenkranz, M.; Felten, J.; Lasok, H.; van Doorn, M.M.; Legué, V.; Palme, K.; Schnitzler, J.-P.; Polle, A. Volatile signalling by sesquiterpenes from ectomycorrhizal fungi reprogrammes root architecture. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourtsoukidis, E.; Behrendt, T.; Yañez-Serrano, A.M.; Hellén, H.; Diamantopoulos, E.; Catão, E.; Ashworth, K.; Pozzer, A.; Quesada, C.A.; Martins, D.L.; et al. Strong sesquiterpene emissions from Amazonian soils. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofikoya, A.O.; Miura, K.; Ghimire, R.P.; Blande, J.D.; Kivimäenpää, M.; Holopainen, T.; Holopainen, J.K. Understorey Rhododendron tomentosum and Leaf Trichome Density Affect Mountain Birch VOC Emissions in the Subarctic. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salehi, B.; Upadhyay, S.; Erdogan Orhan, I.; Kumar Jugran, A.; LD Jayaweera, S.; A Dias, D.; Sharopov, F.; Taheri, Y.; Martins, N.; Baghalpour, N.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of α- and β-Pinene: A Miracle Gift of Nature. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vieira, A.J.; Beserra, F.P.; Souza, M.C.; Totti, B.M.; Rozza, A.L. Limonene: Aroma of innovation in health and disease. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 283, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antonelli, M.; Firenzuoli, F.; Salvarani, C.; Gensini, G.F.; Donelli, D. Reading and interpreting reviews for health professionals: A practical review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med. Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholl, D.; Sohrabi, R.; Huh, J.-H.; Lee, S. The biochemistry of homoterpenes—Common constituents of floral and herbivore-induced plant volatile bouquets. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heil, M. Indirect defence via tritrophic interactions. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brilli, F.; Ciccioli, P.; Frattoni, M.; Prestininzi, M.; Spanedda, A.F.; Loreto, F. Constitutive and herbivore-induced monoterpenes emitted by Populus × euroamericana leaves are key volatiles that orient Chrysomela populi beetles. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L.; Bartolini, G.; Zabini, F. Temporal and Spatial Variability of Volatile Organic Compounds in the Forest Atmosphere. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bach, A.; Yáñez-Serrano, A.M.; Llusià, J.; Filella, I.; Maneja, R.; Penuelas, J. Human Breathable Air in a Mediterranean Forest: Characterization of Monoterpene Concentrations under the Canopy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, V. Estimating the emission of volatile organic compounds (VOC) from the French forest ecosystem. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, G.-Y.; Park, G.-H.; Kim, I.-S.; Bae, J.-S.; Park, H.-Y.; Seo, Y.-G.; Yang, S.-I.; Lee, J.-K.; Jeong, S.-H.; Lee, W.-J. Comparison of Major Monoterpene Concentrations in the Ambient Air of South Korea Forests. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2010, 99, 698–705. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Cho, K.S.; Jeon, Y.; Kim, J.B.; Lim, Y.-R.; Lee, K.; Lee, I.-S. Characteristics and distribution of terpenes in South Korean forests. Hangug Hwangyeong Saengtae Haghoeji 2017, 41, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lerdau, M.; Litvak, M.; Palmer, P.; Monson, R. Controls over monoterpene emissions from boreal forest conifers. Tree Physiol. 1997, 17, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llusia, J.; Peñuelas, J.; Guenther, A.; Rapparini, F. Seasonal variations in terpene emission factors of dominant species in four ecosystems in NE Spain. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 70, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kesselmeier, J.; Staudt, M. Biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOC): An overview on emission, physiology and ecology. J. Atmos. Chem. 1999, 33, 23–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidorov, V.A.; Zenkevich, I.G.; Ioffe, B.V. Volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere of forests. Atmos. Environ. 1985, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.J.B.; Johannes, A.D.V.; Duivenbode, R.V.; Duyzer, J.H.; Verhagen, H.L.M. The determination of terpenes in forest air. Atmos. Environ. 1994, 28, 2413–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-C.; Kim, K.-H. Factors Affecting Ambient Monoterpene Levels in a Pine Forest. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2002, 11, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Woo, J.-S.; Choi, S.-R.; Shin, E.-S. Comparison of Phytoncide (monoterpene) Concentration by Type of Recreational Forest. J. Environ. Health Sci. 2015, 41, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noe, S.M.; Hüve, K.; Niinemets, Ü.; Copolovici, L. Seasonal variation in vertical volatile compounds air concentrations within a remote hemiboreal mixed forest. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 3909–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janson, R. Monoterpene concentrations in and above a forest of scots pine. J. Atmos. Chem. 1992, 14, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk Filipsson, A.; Bard, J.; Karlsson, S. Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 5: Limonene. Available online: https://www.who.int/ipcs/publications/cicad/en/cicad05.pdf?ua=1#:~:text=Limonene%2C%20like%20other%20monoterpenes%2C%20occurs,large%20(Str%C3%B6mvall%2C%201992) (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Courtois, E.A.; Paine, C.E.T.; Blandinieres, P.-A.; Stien, D.; Bessiere, J.-M.; Houel, E.; Baraloto, C.; Chave, J. Diversity of the volatile organic compounds emitted by 55 species of tropical trees: A survey in French Guiana. J. Chem. Ecol. 2009, 35, 1349–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Galbally, I.E.; Porter, N.; Weeks, I.A.; Lawson, S.J. BVOC emissions from mechanical wounding of leaves and branches of Eucalyptus sideroxylon (red ironbark). J. Atmos. Chem. 2011, 68, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmig, D.; Klinger, L.F.; Guenther, A.; Vierling, L.; Geron, C.; Zimmerman, P. Biogenic volatile organic compound emissions (BVOCs). I. Identifications from three continental sites in the U.S. Chemosphere 1999, 38, 2163–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Courtois, E.A.; Dexter, K.G.; Paine, C.E.T.; Stien, D.; Engel, J.; Baraloto, C.; Chave, J. Evolutionary patterns of volatile terpene emissions across 202 tropical tree species. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 2854–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brasseur, G.P.; Prinn, R.G.; Pszenny, A.A.P. Atmospheric Chemistry in a Changing World: An Integration and Synthesis of a Decade of Tropospheric Chemistry Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; ISBN 9783642623967. [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen, J.K.; Blande, J.D. Where do herbivore-induced plant volatiles go? Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Natürliche Aromatische Rohstoffe—Vokabular; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2015.

- Senatore, F. Oli Essenziali; EMSI: Rome, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, M.; Kon, K. Fighting Multidrug Resistance with Herbal Extracts, Essential Oils and Their Components; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780124017085. [Google Scholar]

- Bagetta, G.; Cosentino, M.; Sakurada, T. Aromatherapy: Basic Mechanisms and Evidence Based Clinical Use; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781482246643. [Google Scholar]

- Buckle, J. Clinical Aromatherapy: Essential Oils in Healthcare; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 9780702054402. [Google Scholar]

- Husnu Can Baser, K.; Buchbauer, G. Handbook of Essential Oils: Science, Technology, and Applications, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781466590472. [Google Scholar]

- Sumitomo, K.; Akutsu, H.; Fukuyama, S.; Minoshima, A.; Kukita, S.; Yamamura, Y.; Sato, Y.; Hayasaka, T.; Osanai, S.; Funakoshi, H.; et al. Conifer-Derived Monoterpenes and Forest Walking. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 4, A0042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, J.A.; Hakim, I.A.; Chew, W.; Thompson, P.; Thomson, C.A.; Chow, H.-H.S. Adipose tissue accumulation of d-limonene with the consumption of a lemonade preparation rich in d-limonene content. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.; Göen, T. Human metabolism of α-pinene and metabolite kinetics after oral administration. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterfalvi, A.; Miko, E.; Nagy, T.; Reger, B.; Simon, D.; Miseta, A.; Czéh, B.; Szereday, L. Much More than a Pleasant Scent: A Review on Essential Oils Supporting the Immune System. Molecules 2019, 24, 4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Kobayashi, M.; Wakayama, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; Kawada, T.; Park, B.J.; et al. Effect of phytoncide from trees on human natural killer cell function. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2009, 22, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.S.; Shanahan, D.F.; Fuller, R.A. A Review of the Benefits of Nature Experiences: More than Meets the Eye. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Nakadai, A.; Matsushima, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; Krensky, A.M.; Kawada, T.; Morimoto, K. Phytoncides (Wood Essential Oils) Induce Human Natural Killer Cell Activity. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2006, 28, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, H.C.; Petriello, M.C.; Kim, B.Y.; Do, J.T.; Lim, D.-S.; Lee, H.G.; Han, S.G. Phytoncide Extracted from Pinecone Decreases LPS-Induced Inflammatory Responses in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.Y.; Chang, H.-J.; Lee, S.-K.; Kim, H.-J.; Hwang, J.-K.; Chun, H.S. Amelioration of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice by oral administration of beta-caryophyllene, a sesquiterpene. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-G.; Kim, S.-M.; Min, J.-H.; Kwon, O.-K.; Park, M.-H.; Park, J.-W.; Ahn, H.I.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Oh, S.-R.; Lee, J.-W.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of linalool on ovalbumin-induced pulmonary inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 74, 105706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, H.D.S.; Neto, B.S.; Sousa, D.P.; Gomes, B.S.; da Silva, F.V.; Cunha, F.V.M.; Wanderley, C.W.S.; Pinheiro, G.; Cândido, A.G.F.; Wong, D.V.T.; et al. α-Phellandrene, a cyclic monoterpene, attenuates inflammatory response through neutrophil migration inhibition and mast cell degranulation. Life Sci. 2016, 160, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, J.; Fang, C.; Tang, F. 1,8-cineol attenuates LPS-induced acute pulmonary inflammation in mice. Inflammation 2014, 37, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, A.T.; Ribeiro, M.; Sousa, C.; Judas, F.; Salgueiro, L.; Cavaleiro, C.; Mendes, A.F. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, anti-catabolic and pro-anabolic effects of E-caryophyllene, myrcene and limonene in a cell model of osteoarthritis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 750, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liang, Q.; Lin, A.; Wu, Y.; Min, H.; Song, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yi, L.; Gao, Q. Borneol alleviates brain injury in sepsis mice by blocking neuronal effect of endotoxin. Life Sci. 2019, 232, 116647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, A.F.; Marcon, R.; Dutra, R.C.; Claudino, R.F.; Cola, M.; Leite, D.F.P.; Calixto, J.B. β-Caryophyllene inhibits dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice through CB2 receptor activation and PPARγ pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 178, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, B.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Kechrid, M.; Patel, V.; Tanchian, G.; Wink, D.A.; Gertsch, J.; Pacher, P. β-Caryophyllene ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in a cannabinoid 2 receptor-dependent manner. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Lv, O.; Zhou, F.; Li, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y. Linalool Inhibits LPS-Induced Inflammation in BV2 Microglia Cells by Activating Nrf2. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 1520–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.; Pak, S.C.; Koo, B.-S.; Jeon, S. Borneol alleviates oxidative stress via upregulation of Nrf2 and Bcl-2 in SH-SY5Y cells. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 51, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, J.; Cao, G.; Li, R.; Liu, J.; Dong, Z.; Xu, L. β-Caryophyllene Attenuates Focal Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 1291–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutillas, A.-B.; Carrasco, A.; Martinez-Gutierrez, R.; Tomas, V.; Tudela, J. Thymus mastichina L. essential oils from Murcia (Spain): Composition and antioxidant, antienzymatic and antimicrobial bioactivities. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scherer, M.M.d.C.; de Christo Scherer, M.M.; Marques, F.M.; Figueira, M.M.; Peisino, M.C.O.; Schmitt, E.F.P.; Kondratyuk, T.P.; Endringer, D.C.; Scherer, R.; Fronza, M. Wound healing activity of terpinolene and α-phellandrene by attenuating inflammation and oxidative stress in vitro. J. Tissue Viability 2019, 28, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E.; Ngo, H.T.T.; Park, B.; Seo, S.-A.; Yang, J.-E.; Yi, T.-H. Myrcene, an Aromatic Volatile Compound, Ameliorates Human Skin Extrinsic Aging via Regulation of MMPs Production. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2017, 45, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porres-Martínez, M.; González-Burgos, E.; Carretero, M.E.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Major selected monoterpenes α-pinene and 1,8-cineole found in Salvia lavandulifolia (Spanish sage) essential oil as regulators of cellular redox balance. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Vaibhav, K.; Javed, H.; Tabassum, R.; Ahmed, M.E.; Khan, M.M.; Khan, M.B.; Shrivastava, P.; Islam, F.; Siddiqui, M.S.; et al. 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) mitigates inflammation in amyloid Beta toxicated PC12 cells: Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2014, 39, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, B.; Guo, S. Trans-caryophyllene inhibits amyloid β (Aβ) oligomer-induced neuroinflammation in BV-2 microglial cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 51, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Mou, X.; Huang, J.; Xiong, N.; Li, H. Trans-caryophyllene suppresses hypoxia-induced neuroinflammatory responses by inhibiting NF-κB activation in microglia. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2014, 54, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Liu, Q.F.; Choi, B.; Shin, C.; Lee, B.; Yuan, C.; Song, Y.J.; Yun, H.S.; Lee, I.-S.; Koo, B.-S.; et al. Neuroprotective Effects of Limonene (+) against Aβ42-Induced Neurotoxicity in a Drosophila Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 43, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sabogal-Guáqueta, A.M.; Osorio, E.; Cardona-Gómez, G.P. Linalool reverses neuropathological and behavioral impairments in old triple transgenic Alzheimer’s mice. Neuropharmacology 2016, 102, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.; Lee, K.J.; Zaslawski, C.; Yeung, A.; Rosenthal, D.; Larkey, L.; Back, M. Health and well-being benefits of spending time in forests: Systematic review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Vale, T.G.; do Vale, T.G.; Couto Furtado, E.; Santos, J.G.; Viana, G.S.B. Central effects of citral, myrcene and limonene, constituents of essential oil chemotypes from Lippia alba (Mill.) N.E. Brown. Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.I.G.; de Aquino Neto, M.R.; Teixeira Neto, P.F.; Moura, B.A.; do Amaral, J.F.; de Sousa, D.P.; Vasconcelos, S.M.M.; de Sousa, F.C.F. Central nervous system activity of acute administration of isopulegol in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007, 88, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.-W.; Lin, C.-T.; Chu, F.-H.; Chang, S.-T.; Wang, S.-Y. Neuropharmacological activities of phytoncide released from Cryptomeria japonica. J. Wood Sci. 2009, 55, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.; Lee, C.J. Sleep-enhancing Effects of Phytoncide via Behavioral, Electrophysiological, and Molecular Modeling Approaches. Exp. Neurobiol. 2020, 29, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, R.E.; Campbell, E.L.; Johnston, G.A.R. (+)- And (−)-borneol: Efficacious positive modulators of GABA action at human recombinant alpha1beta2gamma2L GABA(A) receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005, 69, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A.; Sahin-Nadeem, H.; Lummis, S.C.R.; Weigel, I.; Pischetsrieder, M.; Buettner, A.; Villmann, C. GABA(A) receptor modulation by terpenoids from Sideritis extracts. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linck, V.M.; da Silva, A.L.; Figueiró, M.; Caramão, E.B.; Moreno, P.R.H.; Elisabetsky, E. Effects of inhaled Linalool in anxiety, social interaction and aggressive behavior in mice. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto-Maior, F.N.; de Carvalho, F.L.; de Morais, L.C.S.L.; Netto, S.M.; de Sousa, D.P.; de Almeida, R.N. Anxiolytic-like effects of inhaled linalool oxide in experimental mouse anxiety models. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2011, 100, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guzmán-Gutiérrez, S.L.; Bonilla-Jaime, H.; Gómez-Cansino, R.; Reyes-Chilpa, R. Linalool and β-pinene exert their antidepressant-like activity through the monoaminergic pathway. Life Sci. 2015, 128, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán-Gutiérrez, S.L.; Gómez-Cansino, R.; García-Zebadúa, J.C.; Jiménez-Pérez, N.C.; Reyes-Chilpa, R. Antidepressant activity of Litsea glaucescens essential oil: Identification of β-pinene and linalool as active principles. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological Effects of Nature Therapy: A Review of the Research in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, M.; Barbieri, G.; Donelli, D. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarker: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, K.; Kawamoto, M.; Nomura, M.; Otani, H.; Nabika, T.; Gonda, T. Effects of phytoncides on blood pressure under restraint stress in SHRSP. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2004, 31 (Suppl. S2), S27–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akutsu, H.; Kikusui, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Sano, K.; Hatanaka, A.; Mori, Y. Alleviating effects of plant-derived fragrances on stress-induced hyperthermia in rats. Physiol. Behav. 2002, 75, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuhara, M.; Maruyama, K.; Ishii, H.; Masuda, Y.; Sakurai, K.; Tamai, E.; Urakami, K. A Fragrant Environment Containing α-Pinene Suppresses Tumor Growth in Mice by Modulating the Hypothalamus/Sympathetic Nerve/Leptin Axis and Immune System. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 1534735419845139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, S.; Honda, Y.; Kodama, T.; Kimura, M. The Effects of Frankincense Essential Oil on Stress in Rats. J. Oleo Sci. 2019, 68, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, X.-P.; Guo, X.-H.; Geng, D.; Weng, L.-J. d-Limonene protects PC12 cells against corticosterone-induced neurotoxicity by activating the AMPK pathway. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 70, 103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.F.; Bessière, Y. Limonene. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1989, 6, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisserand, R.; Young, R. Essential Oil Safety: A Guide for Health Care Professionals; Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780443062414. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.C.; Siani, A.C.; Ramos, M.F.S.; Menezes-de-Lima, O.J.; Henriques, M.G.M.O. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of essential oils from two Asteraceae species. Pharmazie 2003, 58, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santana, H.S.R.; de Carvalho, F.O.; Silva, E.R.; Santos, N.G.L.; Shanmugam, S.; Santos, D.N.; Wisniewski, J.O.; Junior, J.S.C.; Nunes, P.S.; Araujo, A.A.S.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Limonene in the Prevention and Control of Injuries in the Respiratory System: A Systematic Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 2182–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostan, R.; Béné, M.C.; Spazzafumo, L.; Pinto, A.; Donini, L.M.; Pryen, F.; Charrouf, Z.; Valentini, L.; Lochs, H.; Bourdel-Marchasson, I.; et al. Impact of diet and nutraceutical supplementation on inflammation in elderly people. Results from the RISTOMED study, an open-label randomized control trial. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blowman, K.; Magalhães, M.; Lemos, M.F.L.; Cabral, C.; Pires, I.M. Anticancer Properties of Essential Oils and Other Natural Products. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 3149362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, K.; Büssing, A.; Ostermann, T. Aromatherapy as an adjuvant treatment in cancer care—A descriptive systematic review. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 9, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattenberg, L.W.; Coccia, J.B. Inhibition of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone carcinogenesis in mice by D-limonene and citrus fruit oils. Carcinogenesis 1991, 12, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, J.D.; Lindstrom, M.J.; Gould, M.N. Limonene-induced regression of mammary carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 4021–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Vigushin, D.M.; Poon, G.K.; Boddy, A.; English, J.; Halbert, G.W.; Pagonis, C.; Jarman, M.; Coombes, R.C. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of D-limonene in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Research Campaign Phase I/II Clinical Trials Committee. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1998, 42, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.A.; Lang, J.E.; Ley, M.; Nagle, R.; Hsu, C.-H.; Thompson, P.A.; Cordova, C.; Waer, A.; Chow, H.-H.S. Human breast tissue disposition and bioactivity of limonene in women with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2013, 6, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Erasto, P.; Viljoen, A.M. Limonene—A Review: Biosynthetic, Ecological and Pharmacological Relevance. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 1934578X0800300728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Igimi, H.; Tamura, R.; Toraishi, K.; Yamamoto, F.; Kataoka, A.; Ikejiri, Y.; Hisatsugu, T.; Shimura, H. Medical dissolution of gallstones. Clinical experience of d-limonene as a simple, safe, and effective solvent. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1991, 36, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-W.; Wu, P.-J.; Chiang, B.-H. In vitro neuropeptide Y mRNA expressing model for screening essences that may affect appetite using Rolf B1.T cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 7824–7829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, W.-J.; Lee, N.H.; Hyun, C.-G. Limonene suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced production of nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J. Oleo Sci. 2010, 59, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bai, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, P. Protective Effect of D-Limonene against Oxidative Stress-Induced Cell Damage in Human Lens Epithelial Cells via the p38 Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 5962832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliocchi, L.; Chiappini, C.; Adornetto, A.; Gentile, D.; Cerri, S.; Russo, R.; Bagetta, G.; Corasaniti, M.T. Early LC3 lipidation induced by D-limonene does not rely on mTOR inhibition, ERK activation and ROS production and it is associated with reduced clonogenic capacity of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Phytomedicine 2018, 40, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Toro-Arreola, S.; Flores-Torales, E.; Torres-Lozano, C.; Del Toro-Arreola, A.; Tostado-Pelayo, K.; Guadalupe Ramirez-Dueñas, M.; Daneri-Navarro, A. Effect of D-limonene on immune response in BALB/c mice with lymphoma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2005, 5, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberto, D.; Micucci, P.; Sebastian, T.; Graciela, F.; Anesini, C. Antioxidant activity of limonene on normal murine lymphocytes: Relation to H2O2 modulation and cell proliferation. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 106, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirota, R.; Nakamura, H.; Bhatti, S.A.; Ngatu, N.R.; Muzembo, B.A.; Dumavibhat, N.; Eitoku, M.; Sawamura, M.; Suganuma, N. Limonene inhalation reduces allergic airway inflammation in Dermatophagoides farinae-treated mice. Inhal. Toxicol. 2012, 24, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, G.; Wei, M.; Xie, X.; Soromou, L.W.; Liu, F.; Zhao, S. Suppression of MAPK and NF-κB pathways by limonene contributes to attenuation of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in acute lung injury. Inflammation 2013, 36, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.U.; Tahir, M.; Khan, A.Q.; Khan, R.; Oday-O-Hamiza; Lateef, A.; Hassan, S.K.; Rashid, S.; Ali, N.; Zeeshan, M.; et al. D-limonene suppresses doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress and inflammation via repression of COX-2, iNOS, and NFκB in kidneys of Wistar rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2014, 239, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida, A.A.C.; Silva, R.O.; Nicolau, L.A.D.; de Brito, T.V.; de Sousa, D.P.; Barbosa, A.L.D.R.; de Freitas, R.M.; da Sila Lopes, L.; Medeiros, J.-V.R.; Ferreira, P.M.P. Physio-pharmacological Investigations About the Anti-inflammatory and Antinociceptive Efficacy of (+)-Limonene Epoxide. Inflammation 2017, 40, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Yan, J.; Sun, Z. D-limonene exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties in an ulcerative colitis rat model via regulation of iNOS, COX-2, PGE2 and ERK signaling pathways. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 2339–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, X.; Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Lv, W.; Zhang, S.; Qian, Y.; Deng, X.; Feng, N.; Yu, H.; Qian, B. D-limonene exhibits antitumor activity by inducing autophagy and apoptosis in lung cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 1833–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durço, A.O.; de Souza, D.S.; Heimfarth, L.; Miguel-dos-Santos, R.; Rabelo, T.K.; de Oliveira Barreto, T.; Rhana, P.; Santana, M.N.S.; Braga, W.F.; dos Santos Cruz, J.; et al. d-Limonene Ameliorates Myocardial Infarction Injury by Reducing Reactive Oxygen Species and Cell Apoptosis in a Murine Model. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 3010–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, A.A.C.; de Carvalho, R.B.F.; Silva, O.A.; de Sousa, D.P.; de Freitas, R.M. Potential antioxidant and anxiolytic effects of (+)-limonene epoxide in mice after marble-burying test. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014, 118, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yun, J. Limonene inhibits methamphetamine-induced locomotor activity via regulation of 5-HT neuronal function and dopamine release. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinelli, A.C.; Santos, J.A.; Konkiewitz, E.C.; Oesterreich, S.A.; Formagio, A.S.N.; Croda, J.; Ziff, E.B.; Kassuya, C.A.L. Antihyperalgesic and antidepressive actions of (R)-(+)-limonene, α-phellandrene, and essential oil fromSchinus terebinthifoliusfruits in a neuropathic pain model. Nutr. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-L.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Fan, G.; Ren, J.-N.; Yin, K.-J.; Pan, S.-Y. Antidepressant-like Effect of Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck Essential Oil and Its Main Component Limonene on Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13817–13828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, N.G.P.B.; De Sousa, D.P.; Pimenta, F.C.F.; Alves, M.F.; De Souza, F.S.; Macedo, R.O.; Cardoso, R.B.; de Morais, L.C.S.L.; Melo Diniz, M.d.F.F.; de Almeida, R.N. Anxiolytic-like activity and GC-MS analysis of (R)-(+)-limonene fragrance, a natural compound found in foods and plants. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2013, 103, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Do Amaral, J.F.; Silva, M.I.G.; Neto, M.R.d.A.; Neto, P.F.T.; Moura, B.A.; de Melo, C.T.V.; de Araújo, F.L.O.; de Sousa, D.P.; de Vasconcelos, P.F.; de Vasconcelos, S.M.M.; et al. Antinociceptive effect of the monoterpene R-(+)-limonene in mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Piccinelli, A.C.; Morato, P.N.; Dos Santos Barbosa, M.; Croda, J.; Sampson, J.; Kong, X.; Konkiewitz, E.C.; Ziff, E.B.; Amaya-Farfan, J.; Kassuya, C.A.L. Limonene reduces hyperalgesia induced by gp120 and cytokines by modulation of IL-1 β and protein expression in spinal cord of mice. Life Sci. 2017, 174, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubChem Alpha-Pinene. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/6654 (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- PubChem Beta-Pinene. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/14896 (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Matthys, H.; de Mey, C.; Carls, C.; Ryś, A.; Geib, A.; Wittig, T. Efficacy and tolerability of myrtol standardized in acute bronchitis. A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel group clinical trial vs. cefuroxime and ambroxol. Arzneimittelforschung 2000, 50, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, M.B.; Ahmadi, S. Effectiveness of eucalyptus and cinnamon essential oils compared to permethrin in treatment of head lice infestation. J. Adv. Med. Biomed. Res. 2017, 25, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Oladimeji, F.A.; Orafidiya, O.O.; Ogunniyi, T.A.; Adewunmi, T.A. Pediculocidal and scabicidal properties of Lippia multiflora essential oil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 72, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, L.; Rouse, M.; Wesnes, K.A.; Moss, M. Differential effects of the aromas of Salvia species on memory and mood. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 25, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tildesley, N.T.J.; Kennedy, D.O.; Perry, E.K.; Ballard, C.G.; Savelev, S.; Wesnes, K.A.; Scholey, A.B. Salvia lavandulaefolia (Spanish sage) enhances memory in healthy young volunteers. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003, 75, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N.S.L.; Bollen, C.; Perry, E.K.; Ballard, C. Salvia for dementia therapy: Review of pharmacological activity and pilot tolerability clinical trial. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003, 75, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, A.L.; Figueiredo, C.R.; Arruda, D.C.; Pereira, F.V.; Scutti, J.A.B.; Massaoka, M.H.; Travassos, L.R.; Sartorelli, P.; Lago, J.H.G. α-Pinene isolated from Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae) induces apoptosis and confers antimetastatic protection in a melanoma model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 411, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshida, N.; Takada, T.; Yamamura, Y.; Adachi, I.; Suzuki, H.; Kawakami, J. Inhibitory effects of terpenoids on multidrug resistance-associated protein 2- and breast cancer resistance protein-mediated transport. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Mao, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, R.; Jin, X.; Ye, L. Anti-tumor effect of α-pinene on human hepatoma cell lines through inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 127, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nam, S.-Y.; Chung, C.-K.; Seo, J.-H.; Rah, S.-Y.; Kim, H.-M.; Jeong, H.-J. The therapeutic efficacy of α-pinene in an experimental mouse model of allergic rhinitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 23, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soković, M.; Glamočlija, J.; Marin, P.D.; Brkić, D.; van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antibacterial effects of the essential oils of commonly consumed medicinal herbs using an in vitro model. Molecules 2010, 15, 7532–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elaissi, A.; Rouis, Z.; Mabrouk, S.; Salah, K.B.H.; Aouni, M.; Khouja, M.L.; Farhat, F.; Chemli, R.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F. Correlation between chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oils from fifteen Eucalyptus species growing in the Korbous and Jbel Abderrahman arboreta (North East Tunisia). Molecules 2012, 17, 3044–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.-S.; Lee, H.-J.; Jeon, Y.-D.; Han, Y.-H.; Kee, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Shin, H.-J.; Kang, J.; Lee, B.S.; Kim, S.-H.; et al. Alpha-Pinene Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Activity Through the Suppression of MAPKs and the NF-κB Pathway in Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2015, 43, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, A.T.; Ribeiro, M.; Judas, F.; Salgueiro, L.; Lopes, M.C.; Cavaleiro, C.; Mendes, A.F. Anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective activity of (+)-α-pinene: Structural and enantiomeric selectivity. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkez, H.; Aydın, E. In vitro assessment of cytogenetic and oxidative effects of α-pinene. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2016, 32, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnazar, M.; Bigdeli, M.R.; Parvardeh, S.; Pouriran, R. Attenuating effect of α-pinene on neurobehavioural deficit, oxidative damage and inflammatory response following focal ischaemic stroke in rat. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, I.; Abbasnejad, M.; Haghani, J.; Raoof, M.; Kooshki, R.; Esmaeili-Mahani, S. The effect of central administration of alpha-pinene on capsaicin-induced dental pulp nociception. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, S.; Tomita, T.; Imaizumi, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Hatanaka, A. Effects of plant-derived odors on sleep-wakefulness and circadian rhythmicity in rats. Chem. Senses 2005, 30 (Suppl. S1), i264–i265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Satou, T.; Kasuya, H.; Maeda, K.; Koike, K. Daily inhalation of α-pinene in mice: Effects on behavior and organ accumulation. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 1284–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Woo, J.; Pae, A.N.; Um, M.Y.; Cho, N.-C.; Park, K.D.; Yoon, M.; Kim, J.; Justin Lee, C.; Cho, S. α-Pinene, a Major Constituent of Pine Tree Oils, Enhances Non-Rapid Eye Movement Sleep in Mice through GABAA-benzodiazepine Receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016, 90, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kong, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, R.; Ma, Y.; Song, S.; Liu, J.; Hu, W.; Li, S. Inhalation of Roman chamomile essential oil attenuates depressive-like behaviors in Wistar Kyoto rats. Sci. China Life Sci. 2017, 60, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, H.; Shimada, A.; Suemitsu, S.; Murakami, S.; Kitamura, N.; Wani, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Ishihara, T. Attenuation Effects of Alpha-Pinene Inhalation on Mice with Dizocilpine-Induced Psychiatric-Like Behaviour. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2019, 2019, 2745453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Him, A.; Ozbek, H.; Turel, I.; Oner, A.C. Antinociceptive activity of alpha-pinene and fenchone. Pharmacologyonline 2008, 3, 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Quintão, N.L.; da Silva, G.F.; Antonialli, C.S.; Rocha, L.W.; Cechinel Filho, V.; Cicció, J.F. Chemical composition and evaluation of the anti-hypernociceptive effect of the essential oil extracted from the leaves of Ugni myricoides on inflammatory and neuropathic models of pain in mice. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, D.; Okello, E.; Chazot, P.; Howes, M.-J.; Ohiomokhare, S.; Jackson, P.; Haskell-Ramsay, C.; Khan, J.; Forster, J.; Wightman, E. Volatile Terpenes and Brain Function: Investigation of the Cognitive and Mood Effects of Mentha × Piperita L. Essential Oil with in Vitro Properties Relevant to Central Nervous System Function. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, D.O.; Wightman, E.L. Herbal extracts and phytochemicals: Plant secondary metabolites and the enhancement of human brain function. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk-Filipsson, A.; Löf, A.; Hagberg, M.; Hjelm, E.W.; Wang, Z. d-limonene exposure to humans by inhalation: Uptake, distribution, elimination, and effects on the pulmonary function. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 1993, 38, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlert, C.; van Rensen, I.; März, R.; Schindler, G.; Graefe, E.U.; Veit, M. Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of natural volatile terpenes in animals and humans. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Porres-Martínez, M.; González-Burgos, E.; Carretero, M.E.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. In vitro neuroprotective potential of the monoterpenes α-pinene and 1,8-cineole against H2O2-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells. Z. Naturforsch. C 2016, 71, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzetti, B.B.; Souza, G.E.; Sarti, S.J.; Santos Filho, D.; Ferreira, S.H. Myrcene mimics the peripheral analgesic activity of lemongrass tea. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991, 34, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Oliveira, A.C.; Ribeiro-Pinto, L.F.; Paumgartten, J.R. In vitro inhibition of CYP2B1 monooxygenase by beta-myrcene and other monoterpenoid compounds. Toxicol. Lett. 1997, 92, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.S.; Menezes, A.M.; Viana, G.S. Effect of myrcene on nociception in mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1990, 42, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suntar, I.; Khan, H.; Patel, S.; Celano, R.; Rastrelli, L. An Overview on Citrus aurantium L.: Its Functions as Food Ingredient and Therapeutic Agent. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7864269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Choi, Y.; Choi, S.; Choi, Y.; Park, T. Dietary camphene attenuates hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in mice. Obesity 2014, 22, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girola, N.; Figueiredo, C.R.; Farias, C.F.; Azevedo, R.A.; Ferreira, A.K.; Teixeira, S.F.; Capello, T.M.; Martins, E.G.A.; Matsuo, A.L.; Travassos, L.R.; et al. Camphene isolated from essential oil of Piper cernuum (Piperaceae) induces intrinsic apoptosis in melanoma cells and displays antitumor activity in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 467, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintans-Júnior, L.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Pasquali, M.A.B.; Rabie, S.M.S.; Pires, A.S.; Schröder, R.; Rabelo, T.K.; Santos, J.P.A.; Lima, P.S.S.; Cavalcanti, S.C.H.; et al. Antinociceptive Activity and Redox Profile of the Monoterpenes (+)-Camphene, p-Cymene, and Geranyl Acetate in Experimental Models. ISRN Toxicol. 2013, 2013, 459530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vallianou, I.; Peroulis, N.; Pantazis, P.; Hadzopoulou-Cladaras, M. Camphene, a plant-derived monoterpene, reduces plasma cholesterol and triglycerides in hyperlipidemic rats independently of HMG-CoA reductase activity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Berg, M.; Wendel-Vos, W.; van Poppel, M.; Kemper, H.; van Mechelen, W.; Maas, J. Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, S.V. Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon; UNM Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780826347305. [Google Scholar]

- Hamayon, R. Shamanism and the hunters of the Siberian forest: Soul, life force, spirit. In The Handbook of Contemporary Animism; Acumen Publishing: Slough, UK, 2013; pp. 284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Schellevis, F.G.; Groenewegen, P.P. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, A.C.K.; Maheswaran, R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: A review of the evidence. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotte, D.; Li, Q.; Shin, W.S. International Handbook of Forest Therapy; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781527541740. [Google Scholar]

- ABOUT US|INFOM. Available online: https://www.infom.org/aboutus/index.html (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Martellucci, S. L’Idea Paesaggio. Caratteri Interattivi del Progetto Architettonico e Urbano; Alinea Editrice: Florence, Italy, 2007; ISBN 9788860551320. [Google Scholar]

- Delendi, M.L. Il Progetto di Paesaggio come Dispositivo Terapeutico; Gangemi Editore Spa: Milan, Italy, 2015; ISBN 9788849293487. [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli, E. Scent. Esperienze Olfattive; Politecnico di Milano: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gillis, K.; Gatersleben, B. A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design. Buildings 2015, 5, 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcus, C.C.; Barnes, M. Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; ISBN 9780471192039. [Google Scholar]

- Mencagli, M.; Nieri, M. La Terapia Segreta degli Alberi. L’Energia Nascosta delle Piante e dei Boschi per il Nostro Benessere; Sperling & Kupfer: Milan, Italy, 2020; ISBN 9788855440035. [Google Scholar]

- Firenzuoli, F. Lo Smart Garden del CERFIT (Careggi A.O.U.). Available online: https://www.regione.toscana.it/documents/10180/15989178/MC_41_careggi.pdf/d7e05406-afdc-4867-b8db-f3f94e9cf1f9 (accessed on 29 July 2020).

| Constitutive Forest VOCs | Herbivore-Induced Plant Volatiles (HIPVs) |

|---|---|

| Reduction of abiotic stress. Isoprene and monoterpenes increase general thermal tolerance of photosynthesis, protect photosynthetic apparatus and its activity under high-temperature stress by stabilizing the thylakoid membranes and quenching Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) | Reduction of abiotic stress. Isoprene and monoterpenes increase general thermal tolerance of photosynthesis, protect photosynthetic apparatus and its activity under high-temperature stress by stabilizing the thylakoid membranes and quenching Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) |

| Defense against herbivores. Comprises toxic, repellent, anti-nutritive constitutive BVOCs (biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds) or HIPVs, as well as growth and reproductive reducers | Defense against herbivores, mainly indirectly but also directly. HIPVs and volatile compounds that attract, nourish, or otherwise favor another organism that reduces herbivore pressure |

| Inter-plant signaling. HIPVs, especially Green Leaf Volatiles (GLVs), and constitutive BVOCs can travel from a herbivore-damaged part to other plants (both conspecific and heterospecific), activating defense genes and priming a more vigorous response after an attack | Inter- and intra-plant signaling. HIPVs, especially GLVs, and constitutive BVOCs can travel from a herbivore-damaged part to an undamaged one, or to other plants (both conspecific and heterospecific), activating defense genes and priming a more vigorous response after an attack |

| Defense against microbial pathogens | Defense against microbial pathogens |

| Allelopathy. Inhibition of competing species’ seed germination and competition | |

| Attraction of pollinators and seed dispersers |

| Molecule | Chemical Family | IUPAC | Formula | Structure | CAS number | Boiling Point (at 760 mmHg) | Molar Mass (g/mol) | I/C 1 | C/D 2 | E 3 | P 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoprene | Isoprenoids | 2-methylbuta-1,3-diene | C5H8 |  | 78-79-5 | 34.1 °C | 68.12 | C | D | **** | +++ |

| cis-3-Hexen-1-ol | GLVs | (Z)-hex-3-en-1-ol | C6H12O |  | 928-96-1 | 156.5 °C | 100.16 | I | D | *** | +++ |

| cis-3-Hexenal | GLVs | (Z)-hex-3-enal | C6H10O |  | 6789-80-6 | 126 °C | 98.14 | I | D | *** | +++ |

| cis-3-Hexenyl acetate | GLVs | [(Z)-hex-3-enyl] acetate | C8H14O2 |  | 3681-71-8 | 174.2 °C | 142.2 | I | D | *** | +++ |

| d-Limonene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | (4R)-1-methyl-4-prop-1-en-2-ylcyclohexene | C10H16 |  | 65996-98-7 | 175.4 °C | 136.23 | C, I | D | *** | +/+++ |

| α-Pinene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 2,6,6-trimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene | C10H16 |  | 67762-73-6 | 156 °C | 136.23 | C, I | D | *** | +/+++ |

| (E)-β-Ocimene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | (3E)-3,7-dimethylocta-1,3,6-triene | C10H16 |  | 3779-61-1 | 175.2 °C | 136.23 | C, I | D | ** | +/++ |

| 1,8-Cineole | Monoterpenoid ethers | 1,3,3-trimethyl-2-oxabicyclo[2.2.2]octane | C10H18O |  | 470-82-6 | 176.4 °C | 154.25 | C, I | D | ** | |

| Camphor | Monoterpenoid ketones | 1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-one | C10H16O |  | 76-22-2 | 205.7 °C | 152.23 | ** | |||

| Linalool | Monoterpenoid alcohol | 3,7-dimethylocta-1,6-dien-3-ol | C10H18O |  | 78-70-6 | 197.5 °C | 154.25 | C, L | D | ** | +/++ |

| p-Cymene | Aromatic monoterpene hydrocarbons | 1-methyl-4-propan-2-ylbenzene | C10H14 |  | 99-87-6 | 177 °C | 134.22 | C | D | ** | |

| Sabinene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 4-methylidene-1-propan-2-ylbicyclo[3.1.0]hexane | C10H16 |  | 3387-41-5 | 164 °C | 136.23 | C | D | ** | |

| β-Caryophyllene | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | (1R,4E,9S)-4,11,11-trimethyl-8-methylidenebicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene | C15H24 |  | 87-44-5 | NA | 204.35 | C, I | D | ** | +/++ |

| β-Myrcene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 7-methyl-3-methylideneocta-1,6-diene | C10H16 |  | 123-35-3 | 167 °C | 136.23 | C | D | ** | |

| β-Pinene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 6,6-dimethyl-2-methylidenebicyclo[3.1.1]heptane | C10H16 |  | 127-91-3 | 166.0 °C | 136.234 | C, I | D | ** | |

| β 3-Carene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 3,7,7-trimethylbicyclo[4.1.0]hept-3-ene | C10H16 |  | 74806-04-5 | 171.4 °C | 136.234 | C | D | ** | |

| (E)-Linalool-oxide | Monoterpenoid oxide | 2-[(2S,5S)-5-ethenyl-5-methyloxolan-2-yl]propan-2-ol | C10H18O2 |  | 11063-78-8 | NA | 170.25 | C | D | * | |

| (Z)-Linalool-oxide | Monoterpenoid oxide | 2-(5-ethenyl-5-methyloxolan-2-yl)propan-2-ol | C10H18O2 |  | 14049-11-7 | 224.2 °C | 170.25 | C | D | * | |

| Borneol | Monoterpenoid alcohol | 1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-ol | C10H18O |  | 464-45-9 | 212.0 °C | 154.25 | C | * | ||

| Bornyl acetate | Monoteropene-derived ester | (1,7,7-trimethyl-2-bicyclo[2.2.1]heptanyl) acetate | C12H20O2 |  | 20347-65-3 | 223.5 °C | 196.286 | C | * | ||

| Camphene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 2,2-dimethyl-3-methylidenebicyclo[2.2.1]heptane | C10H16 |  | 79-92-5 | 157.5 °C | 136.234 | C | D | * | |

| Terpinen-4-ol | Monoterpenoid alcohol | 4-methyl-1-propan-2-ylcyclohex-3-en-1-ol | C10H18O |  | 562-74-3 | 209.0 °C | 154.25 | C | * | ||

| α-Copaene | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | (1R)-1,3-dimethyl-8-propan-2-yltricyclo[4.4.0.02,7]dec-3-ene | C15H24 |  | 3856-25-5 | 248.5 °C | 204.35 | I | * | ||

| α-Humulene | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | (1E,4E,8E)-2,6,6,9-tetramethylcycloundeca-1,4,8-triene | C15H24 |  | 6753-98-6 | 166-168 °C | 204.35 | C | D | * | |

| α-Phellandrene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 2-methyl-5-propan-2-ylcyclohexa-1,3-diene | C10H16 |  | 99-83-2 | 171.5 °C | 136.234 | C | * | ||

| α-Terpinene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 1-methyl-4-propan-2-ylcyclohexa-1,3-diene | C10H16 |  | 99-86-5 | 174.1 °C | 136.234 | C | D | * | |

| α-Terpineol | Monoterpenoid alcohol | 2-(4-methylcyclohex-3-en-1-yl)propan-2-ol | C10H18O |  | 10482-56-1 | 217.5 °C | 154.249 | C | * | ||

| α-Terpinolene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 1-methyl-4-propan-2-ylidenecyclohexene | C10H16 |  | 1124-27-2 | 186.0 °C | 138.25 | C | D | * | |

| β-Phellandrene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 3-methylidene-6-propan-2-ylcyclohexene | C10H16 |  | 555-10-2 | 175 °C | 136.234 | C, I | * | +/+++ | |

| β-Terpinene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 1-methyl-4-propan-2-ylcyclohexa-1,4-diene | C10H16 |  | 99-85-4 | 183.0 °C | 136.234 | C, I | D | * | |

| (Z)-β-Ocimene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | (3Z)-3,7-dimethylocta-1,3,6-triene | C10H16 |  | 13877-91-3 | 175.2 °C | 136.234 | C, I | D | +/++ | |

| Bergamotene | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | 6-methyl-2-methylidene-6-(4-methylpent-3-enyl)bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane | C15H24 |  | 7663-66-3 | NA | 208.38 | I | |||

| DMNT | Homoterpene hydrocarbons | 4,8-dimethylnona-1,3,7-triene | C11H18 |  | 19945-61-0 | 195.6 °C | 150.26 | I | +/++ | ||

| Longifolene | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | 3,3,7-trimethyl-8-methylidenetricyclo[5.4.0.02,9]undecane | C15H24 |  | 475-20-7 | 252.2 °C | 204.35 | C | D | ||

| Methyl jasmonate | Jasmonate ester | methyl 2-[(1R,2R)-3-oxo-2-[(Z)-pent-2-enyl]cyclopentyl]acetate | C13H20O3 |  | 39924-52-2 | 302.9 °C | 224.296 | I | |||

| Methyl salicylate | Benzoate ester | methyl 2-hydroxybenzoate | C8H8O3 |  | 119-36-8 | 222.0 °C | 152.147 | I | ++++ | ||

| TMTT | Homoterpene hydrocarbons | (3E,7Z)-4,8,12-trimethyltrideca-1,3,7,11-tetraene | C16H26 |  | 62235-06-7 | 293.2 °C | 218.38 | I | +/++ | ||

| α-Thujene | Monoterpene hydrocarbons | 2-methyl-5-propan-2-ylbicyclo[3.1.0]hex-2-en | C10H16 |  | 2867-05-2 | 152 °C | 136.23 | C | |||

| β-Farnesene | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | 7,11-dimethyl-3-methylidenedodeca-1,6,10-triene | C15H24 |  | 18794-84-8 | 279.6 °C | 204.35 | I | ++ |

| Plant Source | Botanical Family | Part of the Plant Used | Content (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boswellia rivae Engl. | Burseraceae | Oleoresin | 28.0–45.0 |

| Boswellia sacra Flueck | Burseraceae | Oleoresin | 6.0–21.9 |

| Bursera graveolens (Kunth) Triana et Planch | Burseraceae | Oleoresin | 58.6–63.3 |

| Canarium luzonicum (Blume) A. Gray, C. vulgare Leenh. | Burseraceae | Oleoresin | 26.9–65.0 |

| Ravensara aromatica Sonnerat | Lauraceae | Leaves | 13.9–22.5 |

| Abies alba Mill. | Pinaceae | Leaves and branches | 28.5–54.7 |

| Abies spectabilis (D. Don) Spach | Pinaceae | Leaves and branches | 29.6 |

| Pinus mugo Turra | Pinaceae | Leaves and branches | 6.1–37.1 |

| Citrus spp. | Rutaceae | Fruit peel | 27.0–95.0 |

| Type | Doses | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal model—mice | 25 mg orally administered | Limonene reduces mice stomach/lung tumors by 3% | [112] |

| Animal model—rats | 7.5–10% diet | Breast cancer regression in 89% of animals | [113] |

| Phase I—humans | 0.5–12 g/m2 | Partial response in breast cancer patients Absence of progression in subjects with colorectal cancer | [114] |

| Phase II—humans | 8 g/m2 | No responses in patients with solid tumors | [114] |

| Open-label—humans | 2 g/die | 22% reduction in cyclin D1 in early-stage breast cancer | [115] |

| Functional Response | Model | Molecules/Mechanisms Involved in Targeted Pathways | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory Antioxidant | Murine raw 264.7 cell line | TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6 | [119] |

| Human chondrocytes | NF-kB, NO, iNOS, p38, JNK | [70] | |

| Human lens epithelial cells | ROS, CASP, MAPK, Bcl-2/Bax | [120] | |

| Human neuroblastoma cells | LC3, clonogenic capacity | [121] | |

| Fruit fly | NO | [84] | |

| BALB/c mice | NO | [122] | |

| BALB/c mice | Catalase, peroxidase | [123] | |

| BALB/c mice | IL-5, IL-13, MCP-1, TGF-β | [124] | |

| BALB/c mice | NF-kB, p38, JNK, ERK | [125] | |

| Wistar rats | NF-kB, COX-2, iNOS | [126] | |

| Swiss mice | IL-1β | [127] | |

| Sprague–Dawley rats | COX2, ERK, iNOS, MMP-2, MMP-9, PGE, TGF-β | [128] | |

| BALB/c mice | Apoptosis-related genes | [129] | |

| Swiss mice | Oxidative stress | [130] | |

| Anxiolytic Antidepressant Sedative | ICR mice | Elevated plus maze test | [90] |

| Mice | Sleeping time | [88] | |

| Swiss mice | MBT assay, anxiolytic effect | [131] | |

| Rats | Locomotion, dopamine level | [132] | |

| Rats | Immobility in forced swim test | [133] | |

| CUMS mice | Body weight, sucrose preference, mobility | [134] | |

| Mus musculus albino mice | Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) test | [135] | |

| Analgesic | Swiss mice | Induced nociception | [136] |

| ICR mice | Writhing test | [90] | |

| Rats | Mechanical hyperalgesia | [133] | |

| Swiss mice | Writhing test | [127] | |

| Swiss mice | Mechanical hyperalgesia, IL-1β, TNF-α | [137] |

| Plant Source | Botanical Family | Part of the Plant Used | Content (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boswellia frereana Birdwood | Burseraceae | Oleoresin | 41.7–80.0 |

| Boswellia sacra Flueck | Burseraceae | Oleoresin | 10.3–51.3 |

| Cupressus sempervirens L. | Cupressaceae | Leaves | 20.4–52.7 |

| Juniperus communis L. | Cupressaceae | Fruit | 24.1–55.4 |

| Juniperus phoenicea L. | Cupressaceae | Leaves and branches | 41.8–53.5 |

| Dryobalanops aromatica Gaertn | Dipterocarpaceae | Wood | 54.3 |

| Abies alba Mill. | Pinaceae | Cones | 18.0–31.7 |

| Larix laricina Du Roi | Pinaceae | Leaves and branches | 38.5 |

| Picea abies (Mill.) Britton | Pinaceae | Leaves | 14.2–21.5 |

| Pinus divaricata Aiton | Pinaceae | Leaves and branches | 23.1–32.1 |

| Pinus mugo Turra | Pinaceae | Leaves | 4.1–31.5 |

| Pinus nigra J. F. X Arnold | Pinaceae | Leaves | 11.5–35.1 |

| Pinus resinosa Ait. | Pinaceae | Leaves and branches | 47.7–52.8 |

| Pinus strobus L | Pinaceae | Leaves | 30.8–36.8 |

| Pinus sylvestris L | Pinaceae | Leaves | 20.3–45.8 |

| Plant Source | Botanical Family | Part of the Plant Used | Content (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abies alba Mill. | Pinaceae | Cones | 3.0–22.5 |

| Abies balsamea L. | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 28.1–56.1 |

| Picea abies (Mill.) Britton | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 4.8–31.9 |

| Picea glauca (Moench) Voss | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 23.0 |

| Pinus mugo Turra | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 1.3–20.7 |

| Pinus ponderosa Douglas ex P. Lawson & C. Lawson | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 28.9 |

| Pinus resinosa Ait. | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 29.4–29.9 |

| Pinus strobus L. | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 31.1–33.3 |

| Pinus sylvestris L. | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 1.9–33.3 |

| Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carriere | Pinaceae | Leaves and twigs | 20.8 |

| Citrus x aurantifolia Christm. | Rutaceae | Fruit peel | 21.1 |

| Model | Target | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory Antioxidant | Murine macrophages | NF-kB, ERK, JNK | [152] |

| Human U373-MG cells | ROS, peroxidase | [80] | |

| Human chondrocytes | NF-kB, IL-1β, JNK, iNOS, MMP-1, MMP-13 | [153] | |

| Human lymphocytes | Total antioxidant capacity | [154] | |

| Mouse | Ig-E, IL-4 | [149] | |

| Wistar rats | Superoxide dismutase, catalase, peroxidase, NO, IL-6 | [155] | |

| C57BL/6 mice | CD4, CD8 and NK cells | [102] | |

| Wistar rats | COX2 | [156] | |

| Anxiolytic Antidepressant Sedative | Sprague–Dawley rats | Sleep rhythm | [157] |

| Mice | BDNF, TH, EPM test | [158] | |

| ICR and C57BL/6N mice | GABA BZD receptor, sleep behavior | [159] | |

| Wistar–Kyoto mice | Forced swim test, oxidative phosphorylation expression | [160] | |

| Wistar rats | Sensorimotor severity score | [155] | |

| C57BL/6 mice | Schizophrenia-like behavior | [161] | |

| Analgesic | BALB/c mice | Tail-flick test | [162] |

| Mice | Neuropathic pain | [163] | |

| Wistar rats | Nociception | [156] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D.; Barbieri, G.; Valussi, M.; Maggini, V.; Firenzuoli, F. Forest Volatile Organic Compounds and Their Effects on Human Health: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6506. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17186506

Antonelli M, Donelli D, Barbieri G, Valussi M, Maggini V, Firenzuoli F. Forest Volatile Organic Compounds and Their Effects on Human Health: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(18):6506. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17186506

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntonelli, Michele, Davide Donelli, Grazia Barbieri, Marco Valussi, Valentina Maggini, and Fabio Firenzuoli. 2020. "Forest Volatile Organic Compounds and Their Effects on Human Health: A State-of-the-Art Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 18: 6506. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17186506