Globalization, Work, and Health: A Nordic Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Nordic Working Life Model: A Brief Overview

3.1.1. Macro Perspectives

3.1.2. Micro Perspectives

3.1.3. Trust Binds Macro and Micro Together

3.1.4. Democratic Innovation

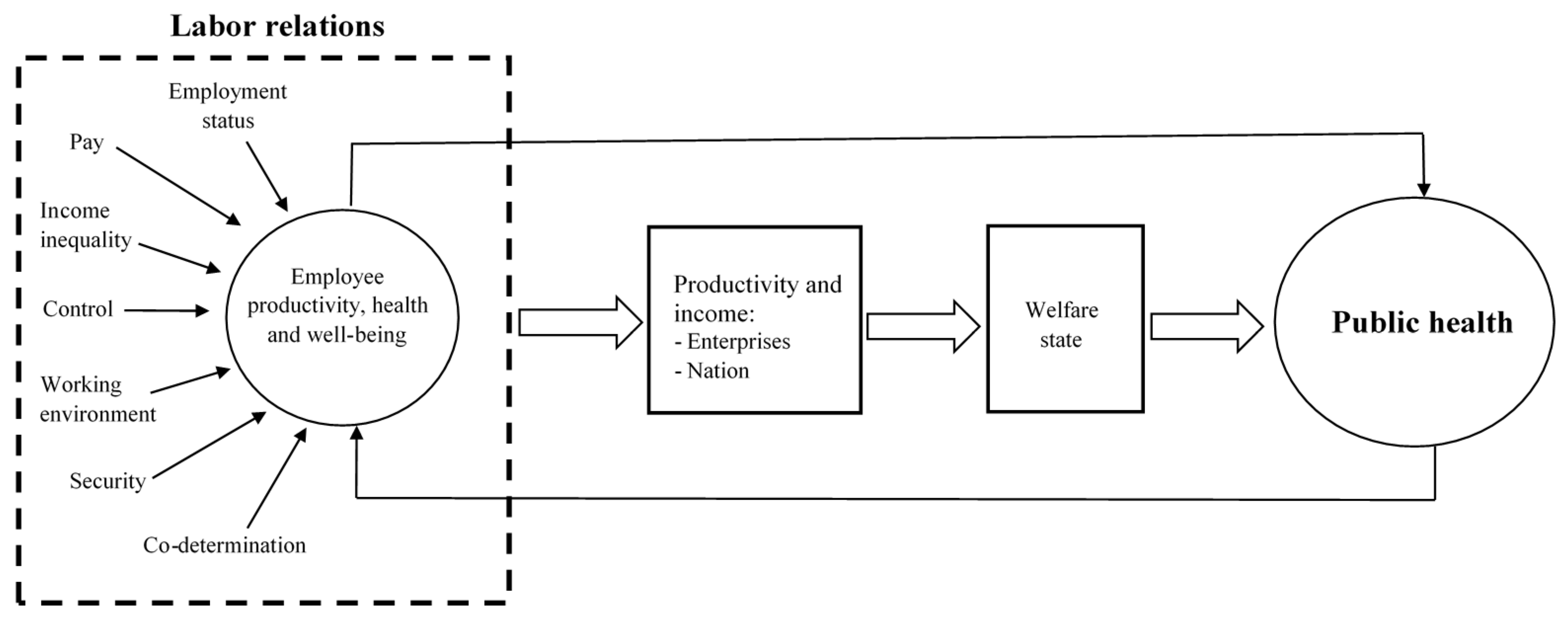

3.2. Employment, Working Environment, and Health

3.3. How Globalization Affects Labor Markets

3.3.1. Migration

3.3.2. From Standard to Atypical Employment Relationships

3.4. How New Technology Affects Labor Relations

3.4.1. The Platform Economy

3.4.2. Automation and Digitalization

3.5. Changing Management Culture

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationships between Globalization, the Nordic Working Life Model, Inequality, Trust, and Public Health

4.2. Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milanovic, B. Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, D. The Globalization Paradox: Why Global Markets, States, and Democracy Can't Coexist; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grimalda, G.; Trannoy, A.; Filgueira, F.; Moene, K.O. Egalitarian redistribution in the era of hyper-globalization. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2020, 78, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPS—International Panel on Social Progress. Rethinking Society for the 21st Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, O.; Palme, P. Social Policy and Economic Development in the Nordic Countries; Palgrave Macmillian: Hampshire, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moene, K. Scandinavian equality: A prime example of protection without protectionism. In The Quest for Security: Protection without Protectionism and the Challenge of Global Governance; Stiglitz, J., Kaldor, M., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pontusson, J. Inequality and Prosperity: Social Europe vs. Liberal America; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Valkonen, T.; Vihriälä, V. The Nordic Model—Challenged but Capable of Reform; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vike, H. Politics and Bureaucracy in the Norwegian Welfare State: An Anthropological Approach; Palgrave Macmillian: Hampshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. The Health Gap. The Challenge of an Unequal World; Bloomsbury Publishing PLC: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. Nordic leadership and global activity on health equity through action on social determinants of health. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 46, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raphael, D. Challenges to promoting health in the modern welfare state: The case of the Nordic nations. Scand. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey—Overview Report; Eurofound: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviewes: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Calmfors, L. How well is the Nordic model doing? Recent performance and future challenges. In The Nordic Model—Challenged but Capable of Reform; Valkonen, T., Vihriälä, V., Eds.; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, R.; Pickett, K. The Inner Level: How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone’s Well-Being; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Løken, E.; Stokke, T.A.; Nergaard, K. Labour Relations in Norway; Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research: Oslo, Norway, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moene, K.O.; Wallerstein, M. How social democracy worked: Labor-market institutions. Politics Soc. 1995, 23, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moene, K.; Wallerstein, M. Pay inequality. J. Labor Econ. 1997, 15, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moene, K.; Wallerstein, M. Social democracy as a development strategy. In Globalization and Egalitarian Redistribution; Bardhan, P., Bowles, S., Wallerstein, M., Eds.; Russel Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, S.K.; Dølvik, J.E.; Ibsen, C.L. Nordic Labour Market Models in Open Markets; ETUI Printshop: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, S. Frontfagsmodellen—fortsatt egnet? [The frontline model—still viable?]. In Fred Er Dog Det Beste. Riksmekleren Gjennom Hundre År [Peace is After all the Best. The National Mediator for a 100 Years]; Dalseide, N., Ed.; Pax forlag: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.; Dølvik, J.E.; Ibsen, C.; Schulten, T. The manufacturing sector: Still an anchor for pattern bargaining within and across countries? Eur. J. Ind. Relat. 2018, 24, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, E.; Moene, K.O.; Willumsen, F. The Scandinavian model—An interpretation. J. Public Econ. 2014, 117, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barth, E.; Moene, K. The equality multiplier: How wage compression and welfare empowerment interact. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2016, 14, 1011–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, S.; Rothstein, B. Trusting other people. J. Public Affairs 2017, 16, e1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E.M. The Moral Foundation of Trust; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, G.; Mocetti, S. Inequality and trust: New evidence from panel data. Econ. Inq. 2016, 54, 794–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothstein, B.; Samanni, M.; Teorell, J. Explaining the welfare state: Power resources vs. the quality of government. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2012, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, S.; Bjørnstad, R.; Mark, M.S. Den Norske Arbeidslivsmodellen Med Produktivitet I Verdenstoppen [The Norwegian Working Life Model with the Best Productivity in the World]; Report 37; Samfunnsøkonomisk analyse: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R. Who Can You Trust?: How Technology Brought Us Together—and Why It Could Drive Us Apart; Portfolio Penguin: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- van der Noordt, M.; IJzelenberg, H.; Droomers, M.; Proper, K. Health effects of employment: A systematic review of prospective studies. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 71, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddel, G.; Burton, A. Is Work Good For Your Health? TSO: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen, E.Q.; Fujishiro, K.; Cunningham, T.; Flynn, M. Work as an inclusive part of population health inequities research and prevention. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsbergis, P.A. Assessing the contribution of working conditions to socioeconomic disparities in health: A commentary. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlum, I.S. Betydningen av arbeidsmiljø for sosiale ulikheter i helse [The Importance of Working Environment on Social Inequality in Health]; National Insitute of Occupational Health: Oslo, Norway, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, V.; Kristensen, T.S. Social class and self-rated health: Can the gradient be explained by differences in life style or work environment? Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagestad, C.; Bjerkan, A.M.; Gravseth, H.M.U. Arbeidsmiljøet i Norge og EU—En sammenligning [Working Environment in Norway and EU—a Comparison]; National Institute of Occupational Health: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work. Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Falkum, E.; Ingelsrud, M.H.; Nordrik, B. Medbestemmelsesbarometeret 2016 [The Co-Determination Survey 2016]; Work Research Institute, Oslo and Akershus University College: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Constitution of the World Health Organization. Available online: http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Torp, S. Hva er helsefremmende arbeidsplasser—og hvordan skapes det? [What are healthy workplaces - and how can they be created?]. Swedish J. Soc. Med. 2013, 90, 768–779. [Google Scholar]

- Drobnič, S.; Beham, B.; Präg, P. Good job, good life? Working conditions and quality of life in Europe. J. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 99, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torp, S.; Grimsmo, A.; Hagen, S.; Duran, A.; Gudbergsson, S.B. Work engagement: A practical measure for workplace health promotion? Health Promot. Int. 2013, 28, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marmot, M.G.; Rose, G.; Shipley, M.; Hamilton, P.J. Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. J. Epidemiol. Community Heal. 1978, 32, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marmot, M.G.; Smith, G.D.; Stansfeld, S.; Patel, C.; North, F.; Head, J.; White, I.; Brunner, E.; Feeney, A. Health inequalities among British civil servants: The Whitehall II study. Lancet 1991, 337, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, C.T.; Shipley, M.J.; van de Mheen, H.; Grobbee, D.E.; Marmot, M.G. Employment grade differences in cause specific mortality. A 25 year follow up of civil servants from the first Whitehall study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimaki, M.; Vahtera, J.; Virtanen, M.; Elovainio, M.; Pentti, J.; Ferrie, J.E. Temporary employment and risk of overall and cause-specific mortality. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 158, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Benach, J.; Gimeno, D.; Benavides, F.G.; Martinez, J.M.; Torne Mdel, M. Types of employment and health in the European Union: Changes from 1995 to 2000. Eur. J. Public Heal. 2004, 14, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cummings, K.J.; Kreiss, K. Contingent workers and contingent health: Risks of a modern economy. JAMA 2008, 299, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Kivimaki, M.; Joensuu, M.; Virtanen, P.; Elovainio, M.; Vahtera, J. Temporary employment and health: A review. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howard, J. Nonstandard work arrangements and worker health and safety. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aronsson, G.; Bejerot, E.; Härenstam, A. Healthy work: Ideal and reality among public and private employed academics in Sweden. Public Pers. Manag. 1999, 28, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, I.K.; Konijn, E.A.; Righetti, F.; Rusbult, C.E. A healthy dose of trust: The relationship between interpersonal trust and health. Pers. Relatsh. 2011, 18, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dølvik, J.E.; Fløtten, T.; Hippe, J.M.; Jordfald, B. Den Nordiske Modellen Mot 2030. Et Nytt Kapittel? [The Nordic Model towards 2030. A New Chapter?]; Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Djuve, A.B.; Grødem, A.S. Innvandring Og Arbeidsmarkedsintegrering I Norden [Immigration and Labor Market Intergration in the Nordic Countries]; Fafo-report 2014:27; Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meld.St.13 (2018–2019). Muligheter for Alle. Fordeling og Sosial Bærekraft [Opportunities for All. Distribution and Social Sustainability]; Ministry of Finance: Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnstad, R. Virkninger av Allmenngjøring av Tariffavtaler [Effects of Generalization of Collective Agreements]; Economics Norway: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hoen, M.F.; Markussen, S.; Røed, K. Immigration and Social Mobility; Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Er Innvandring Virkelig Årsaken? [Is Immigation Really the Cause?]. Available online: https://www.dn.no/innlegg/innvandring/arbeidsliv/eos/er-innvandring-virkelig-arsaken/2-1-537112 (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Standing, G. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eldring, L.; Ørjasæter, E. Løsarbeidersamfunnet [The Freelance Society]; Cappelen Damm Akademisk: Oslo, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ingelsrud, M.H.; Warring, N.; Gleerup, J.; Hansen, P.B.; Jakobsen, A.; Underthun, A.; Weber, S.S. Precarity in Nordic working life? In Work and Wellbeing in the Nordic Countries. Critical Perspectives on the World's Beset Working Lives; Hvid, H., Falkum, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Elstad, L.; Ullmann, B. Ulovlig Innleie i Byggebransjen i Hovedstadsområdet Våren 2017 [Illegal Hiring in the Construction Industry in the Capital Area in Spring 2017]; Fellesforbundet, Elektromontørenes Forening, Oslo Bygningsarbeiderforening, Rørleggernes Fagforening, Tømrer og Byggfagforeningen: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. Høringsnotat om Endringer i Arbeidsmiiljøloven om Fast Ansettelse, Midlertidig Ansettelse i og Innleie Fra Bemannigsforetak. [Consultation Note on Amendments to the Working Environment Act on Permanent Employment, Temporary Employment in and Hiring from Staffing Companies]; Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NOU. Arbeidstidsutvalget. Regulering av Arbeidstid—Vern og Fleksibilitet [The Working Hours Committee. Regulation of Working Time—Frotection and Flexibility]; Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 96/71/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 1996 Concerning the Posting of Workers in the Framework of the Provision of Services. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A31996L0071 (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Cremers, J. In Search of Cheap Labour in Europe. Working and Living Condeitions of Posted Workers; International Books: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. The many faces of self-employment in Europe. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/blog/the-many-faces-of-self-employment-in-europe (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Nergaard, K. Tilknytningsformer i Norsk Arbeidsliv. Nullpunktsanalyse. [Forms of Affiliations to Norway's Labor Market. A Zero-Point Analysis]; Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grünfeld, L.; Salvanes, K.; Hvide, H.; Jensen, T.; Skogstrøm, J.F. Selvstendig Næringsdrivende i Norge. Hvem er de og Hva Betyr de for Fremtidens Arbeidsmarked? [Self-Employed People in Norway—Who Are They and How Will They Affect the Future Labour Market?]; Menon: Bergen, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NOU. Delingsøkonomien—Muligheter og Utfordringer [The Sharing Econom—Opportunities and Challenges]; Decision Support System: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, S.S. Working life on Nordic labour platforms. In Work and Wellbeing in the Nordic Countries. Critical Perspectives on the World's Best Working Lives; Hvid, H., Falkum, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 339–358. [Google Scholar]

- Alsos, K.; Jesnes, K.; Øistad, B. Når sjefen er en app—Delingsøkonomi i et arbeidsperspektiv [When the boss is an app—Sharing economy in a labor perspective]. Praktisk Øk. Finans 2018, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, K.J.; Guldvik, R.E. Arbeidslivet remikses [Re-mixing working life]. MAGMA 2016, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn-Rasmussen, P.; Klethagen, P. International management concepts meeting Nordic working life. In Work and Wellbeing in the Nordic Countries. Critical Perspectives on the World's Best Working Lives; Hvid, H., Falkum, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stugu, S. Du har sparken. Om HR og Amerikanisering av Norsk Arbeidsliv [You Are Fired. About HR and Americanization of Norwegian Working Life]; Forlaget Manifest: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, H.L. New working time and new temporalities: The erosion of influence and rythms in work. In Work and Wellbeing in the Nordic Countries. Critical Perspectives on the World’s Best Working Lives; Hvid, H., Falkum, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. Agreement on a More Inclusive Working Life. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/fc3b4fed90b146499b90947491c846ad/the-ia-agreement-20192022.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Kamp, A.; Hansen, A.G.; Wathne, C.T. Nordic approaches to New Public Management: Professions in transition—introduction. In Work and Wellbeing in the Nordic Countries. Critical Perspectives on the World's Beste Working Lives; Hvid, H., Falkum, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 217–282. [Google Scholar]

- Reiersen, J.; Torp, S. The Nordic income equality model in health promotion. Swedish J. Soc. Med. 2020, 97, 405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G. Democratic Innovations; Cambridge Universtiy Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, A. Putting the public back into governance: The challenges of citizen participation and its future. Public Admin. Rev. 2015, 75, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | GDP Per Capita 1 | Union Density 2 | Bargaining Coverage 3 | Wage Inequality 4 | Poverty Rate 5 | Trust 6 | Temporary Employment 7 | Work Satisfaction 8 | Life Satisfaction 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordic countries | 55,842 | 66.7 | 85.2 | 2.5 | 7.0 | 65.0 | 11.6 | 36.3 | 9.6 |

| Denmark | 55,138 | 66.5 | 82.0 | 2.6 | 5.5 | 64.5 | 10.9 | 47.0 | 9.7 |

| Finland | 48,248 | 60.3 | 89.3 | 2.6 | 6.3 | 58.0 | 15.6 | 28.0 | 10.0 |

| Iceland | 57,453 | 91.8 | 92.0 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 7.8 | 9.5 | ||

| Norway | 65,603 | 49.2 | 72.5 | 2.5 | 8.4 | 73.7 | 8.0 | 44.0 | 9.9 |

| Sweden | 52,766 | 65.6 | 90.0 | 2.1 | 9.3 | 63.8 | 16.6 | 26.0 | 8.9 |

| Continental Europe | 52,240 | 23.7 | 85.4 | 3.0 | 9.3 | 313 | 13.7 | 30.4 | 7.8 |

| Austria | 55,529 | 26.3 | 98.0 | 3.1 | 9.8 | 8.7 | 41.0 | 8.3 | |

| Belgium | 50,442 | 50.3 | 96.0 | 2.5 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 29.0 | 7.6 | |

| France | 45,149 | 8.8 | 98.5 | 3.0 | 8.3 | 18.7 | 16.4 | 21.0 | 6.1 |

| Germany | 53,752 | 16.5 | 56.0 | 3.3 | 10.4 | 32.1 | 12.0 | 30.0 | 7.8 |

| Netherlands | 56,326 | 16.4 | 78.6 | 3.0 | 8.3 | 43.0 | 20.3 | 31.0 | 9.3 |

| Southern Europe | 35,990 | 20.9 | 65.8 | 3.1 | 14.0 | 23.7 | 19.1 | 19.1 | 3.6 |

| Greece | 29,592 | 20.2 | 25.5 | 3.2 | 14.4 | 12.5 | 23.0 | 2.2 | |

| Italy | 41,426 | 34.3 | 80.0 | 2.3 | 13.7 | 28.3 | 16.7 | 18.0 | 4.4 |

| Portugal | 33,035 | 15.3 | 73.9 | 3.6 | 12.5 | 20.8 | 18.0 | 2.4 | |

| Spain | 39,908 | 13.6 | 83.6 | 3.1 | 15.5 | 19.0 | 26.3 | 5.5 | |

| UK | 45,505 | 23.4 | 26.3 | 3.4 | 11.1 | 30.0 | 5.2 | 37.0 | 7.2 |

| USA | 62,480 | 10.1 | 11.5 | 5.0 | 17.8 | 38.2 | 4.0 | 7.4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torp, S.; Reiersen, J. Globalization, Work, and Health: A Nordic Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7661. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17207661

Torp S, Reiersen J. Globalization, Work, and Health: A Nordic Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7661. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17207661

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorp, Steffen, and Jon Reiersen. 2020. "Globalization, Work, and Health: A Nordic Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7661. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17207661