Effectiveness of an Adapted Physical Activity Protocol for Upper Extremity Recovery and Quality of Life Improvement in a Case of Seroma after Breast Cancer Treatment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Description

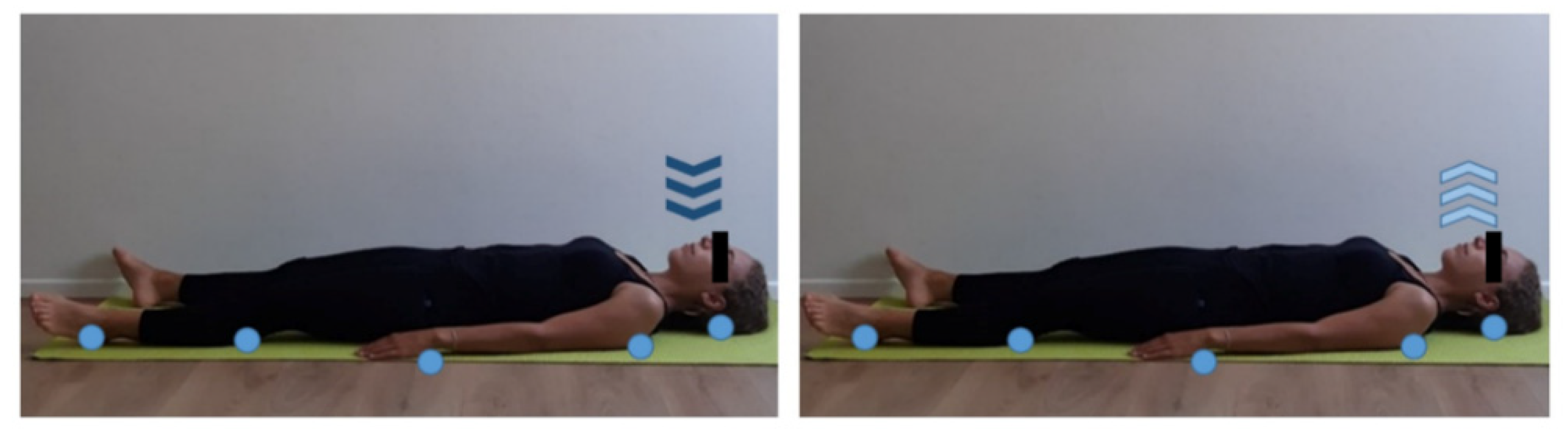

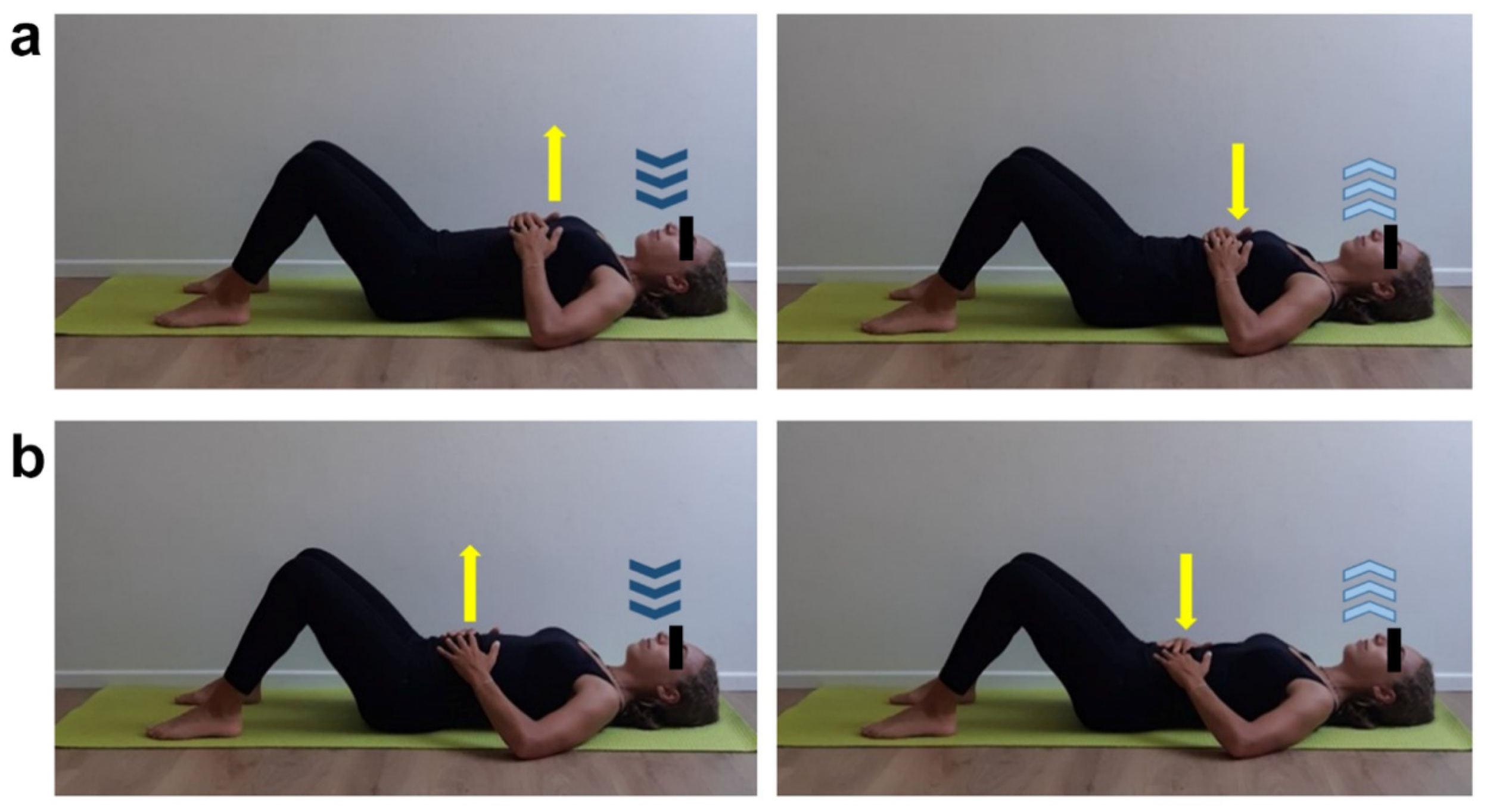

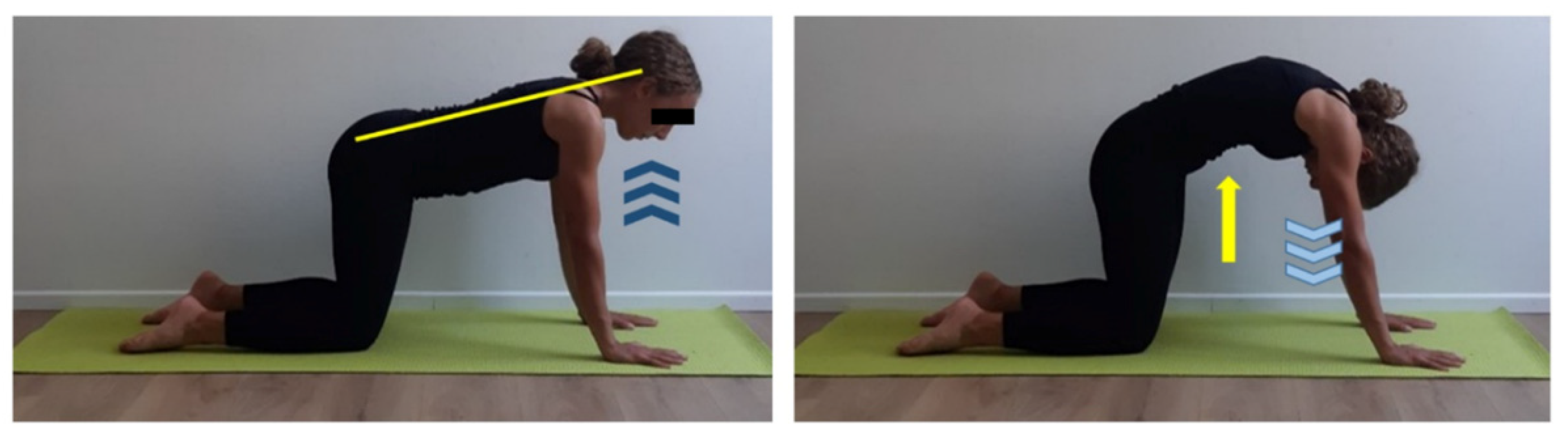

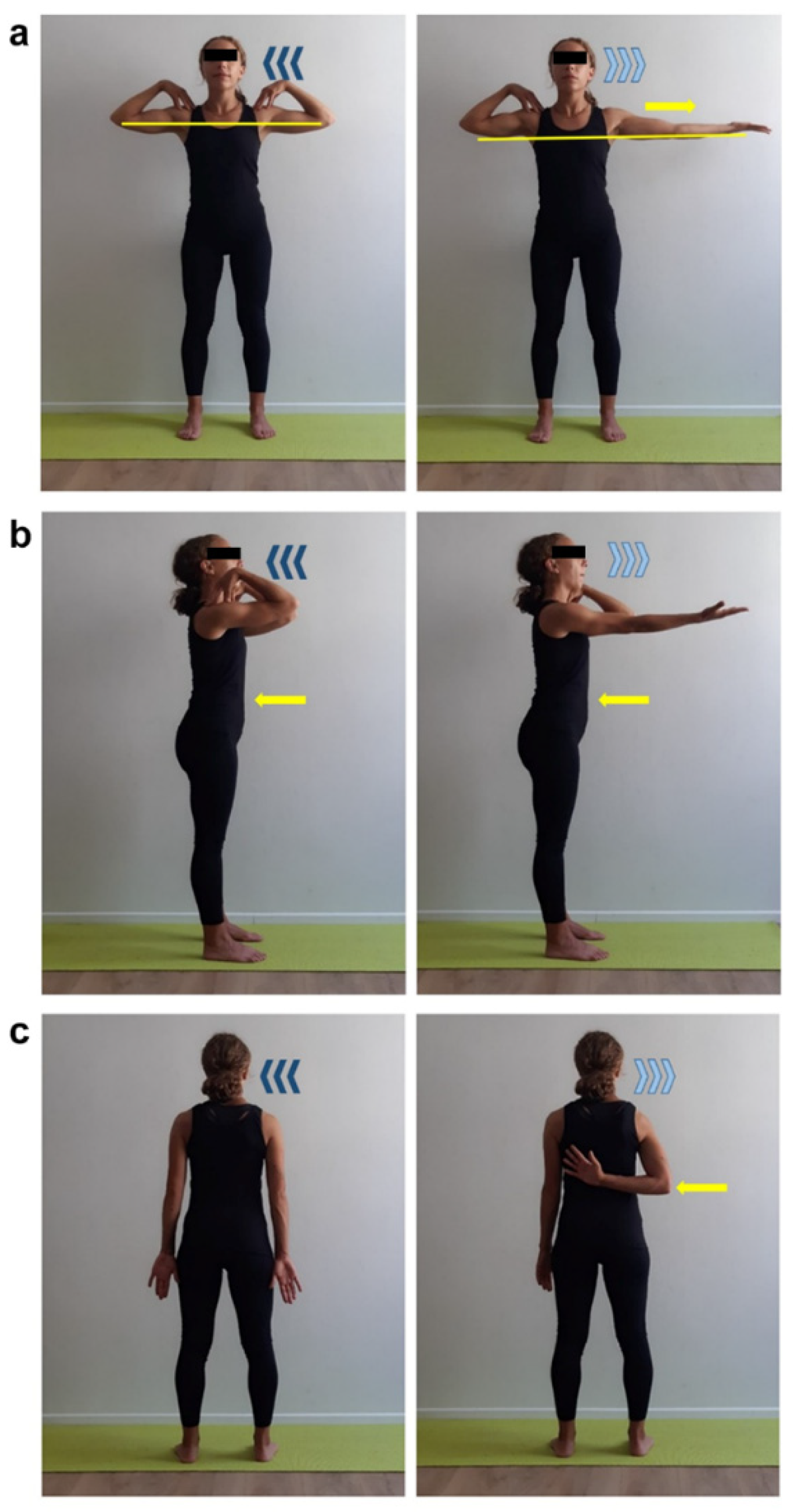

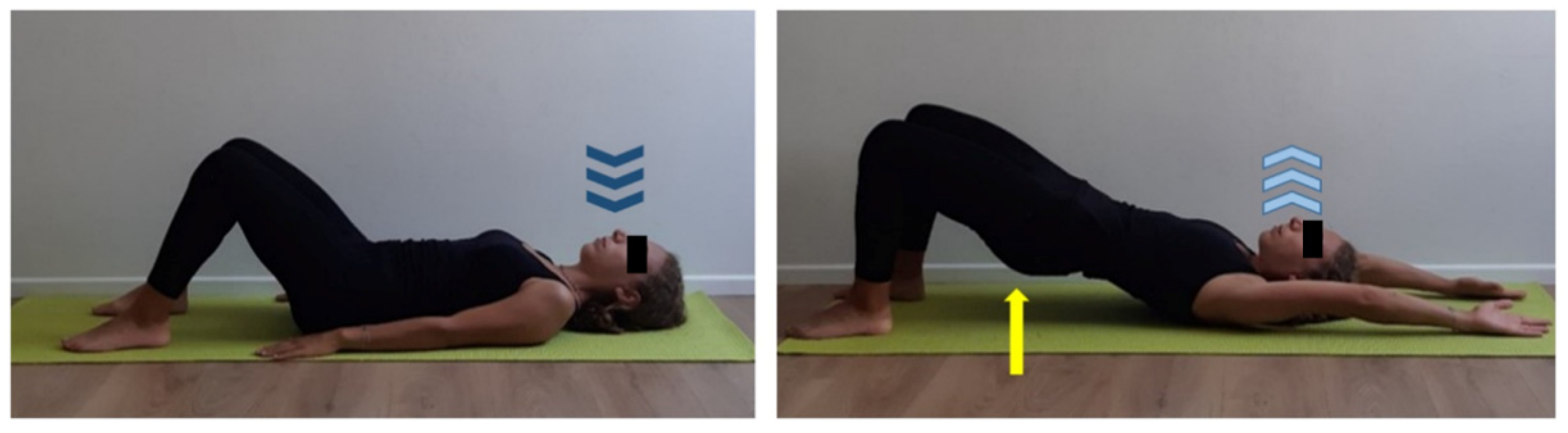

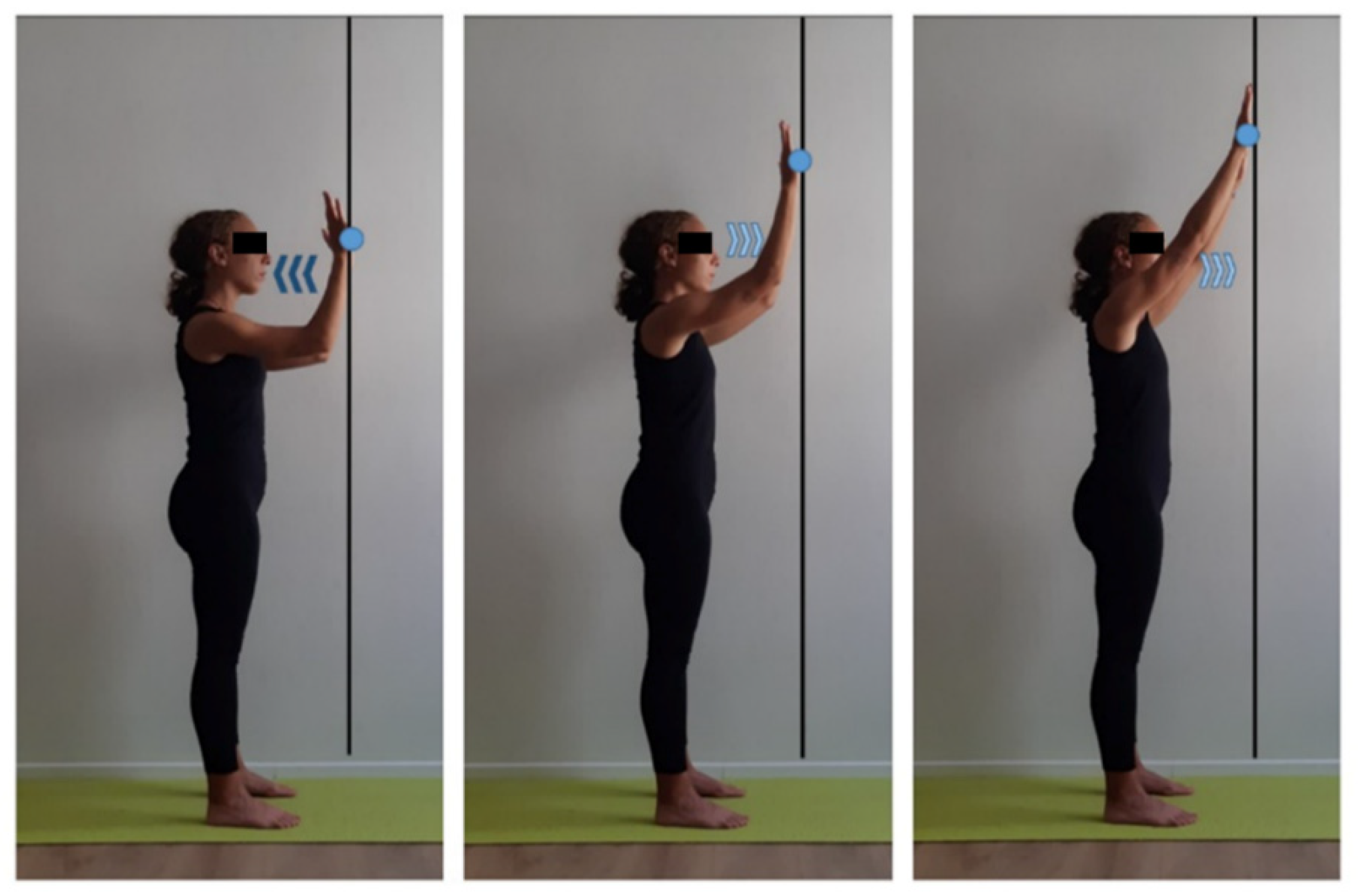

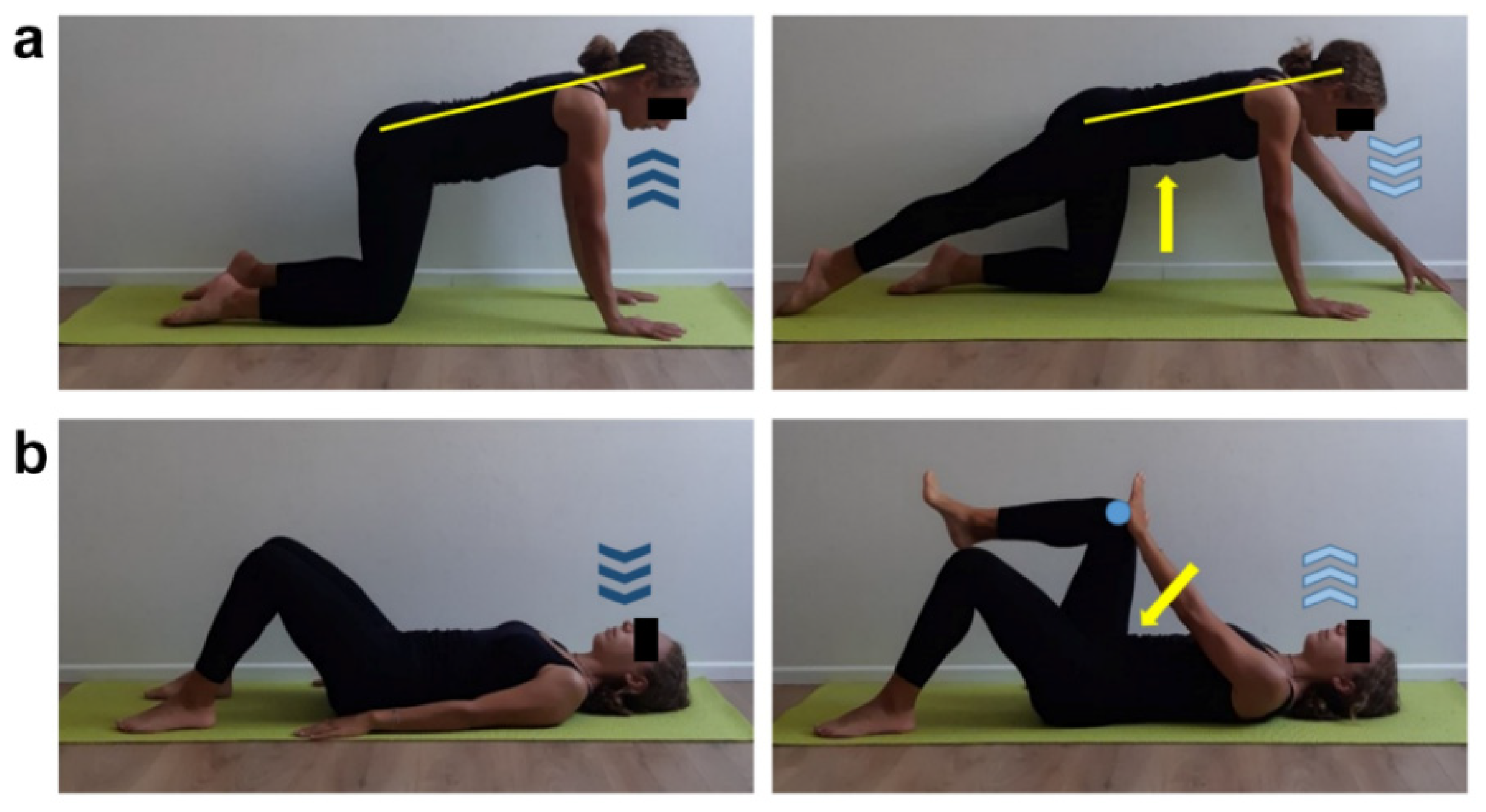

2.2. Structured Physical Activity Protocol

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rostas, J.W.; Dyess, D.L. Current operative management of breast cancer: An age of smaller resections and bigger cures. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2012, 2012, 516417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riis, M. Modern surgical treatment of breast cancer. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 56, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirandola, D.; Monaci, M.; Miccinesi, G.; Ventura, L.; Muraca, G.M.; Casini, E.; Sgambati, E.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. Long-term benefits of adapted physical activity on upper limb performance and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2017, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidding, J.T.; Beurskens, C.H.G.; van der Wees, P.J.; van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G. Treatment related impairments in arm and shoulder in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirandola, D.; Miccinesi, G.; Muraca, M.G.; Belardi, S.; Giuggioli, R.; Sgambati, E.; Manetti, M.; Monaci, M.; Marini, M. Longitudinal assessment of the impact of adapted physical activity on upper limb disability and quality of life in breast cancer survivors from an Italian cohort. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhee, D.E.; Steele, J.R. Physical side-effects following breast reconstructive surgery impact physical activity and function. Support. Care Cancer 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester-Hvid, A.; Avnstorp, M.B.; Wagenblast, L.; Lock-Andersen, J.; Matzen, S.H. Case report: Breast seroma mimicking breast implants. Int. J. Surg. Case. Rep. 2017, 40, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Hai, J.; Mao, J.; Dong, X.; Xiao, Z. Quilting suture is better than conventional suture with drain in preventing seroma formation at pectoral area after mastectomy. BMC Surg. 2020, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourmouzi, D.; Vryzas, T.; Drevelegas, A. New spontaneous breast seroma 5 years after augmentation: A case report. Cases J. 2009, 2, 7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Penttinen, H.; Utriainen, M.; Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P.L.; Raitanen, J.; Sievänen, H.; Nikander, R.; Blomqvist, C.; Huovinen, R.; Vehmanen, L.; Saarto, T. Effectiveness of a 12-month exercise intervention on physical activity and quality of life of breast cancer survivors; five-year results of the BREX-study. In Vivo 2019, 33, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirandola, D.; Franchi, G.; Maruelli, A.; Vinci, M.; Muraca, M.G.; Miccinesi, G.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. Tailored sailing experience to reduce psychological distress and improve the quality of life of breast cancer survivors: A survey-based pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, T.; Bracha, J. Identification of signs and symptoms of axillary web syndrome and breast seroma during a course of physical therapy 7 months after lumpectomy: A case report. Phys. Ther. 2019, 99, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirandola, D.; Miccinesi, G.; Muraca, M.G.; Sgambati, E.; Monaci, M.; Marini, M. Evidence for adapted physical activity as an effective intervention for upper limb mobility and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, N.; Cruz, J. The pectoralis minor muscle and shoulder movement-related impairments and pain: Rationale, assessment and management. Phys. Ther. Sport 2016, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soerjomataram, I.; Louwman, M.W.J.; Ribot, J.G.; Roukema, J.A.; Coebergh, J.W.W. An overview of prognostic factors for long-term survivors of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008, 107, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.B.; Gwark, S.C.; Kang, C.M.; Sohn, G.; Kim, J.; Chung, I.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Ko, B.S.; Ahn, S.H.; et al. The effects of poloxamer and sodium alginate mixture (Guardix-SG®) on range of motion after axillary lymph node dissection: A single-center, prospective, randomized, double-blind pilot study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Chung, S.Y.; Kim, W.Y.; Yang, S.N. Effect of breast cancer surgery on chest tightness and upper limb dysfunction. Medicine 2019, 98, e15524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Basu, S.; Shukla, V.K. Seroma formation after breast cancer surgery: What we have learned in the last two decades. J. Breast Cancer 2012, 15, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirandola, D.; Muraca, M.G.; Sgambati, E.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. Role of a structured physical activity pathway in improving functional disability, pain and quality of life in a case of breast and gynecological cancer survivorship. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tait, R.C.; Zoberi, K.; Ferguson, M.K.; Levenhagen, K.; Luebbert, R.A.; Rowland, K.; Salsich, G.B.; Herndon, C. Persistent post-mastectomy pain: Risk factors and current approaches to treatment. J. Pain 2018, 19, 1367–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, W.A.; Monteiro, M.N.; Queiroz, J.F.; Gonçalves, A.K. Pain and quality of life in breast cancer patients. Clinics 2017, 72, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadivelu, N.; Schreck, M.; Lopez, J.; Kodumudi, G.; Narayan, D. Pain after mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Am. Surg. 2008, 74, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, M.; Bendinelli, B.; Assedi, M.; Occhini, D.; Castaldo, M.; Fabiano, J.; Petranelli, M.; Migliolo, M.; Monaci, M.; Masala, G. Low back pain in healthy postmenopausal women and the effect of physical activity: A secondary analysis in a randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variables | Baseline | Post-APA1 | Post-APA2 | Post-AF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical limb ROM | ||||

| Flexion (°) | 145 | 155 | 180 | 180 |

| Extension (°) | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| External rotation (°) | 55 | 60 | 75 | 90 |

| Abduction (°) | 110 | 120 | 180 | 180 |

| Non-surgical limb ROM | ||||

| Flexion (°) | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| Extension (°) | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| External rotation (°) | 80 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Abduction (°) | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| Surgical shoulder mobility (cm) | 29 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-surgical shoulder mobility (cm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgical shoulder PMm length test (cm) | 13 | 10.5 | 9 | 8 |

| Non-surgical shoulder PMm length test (cm) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Sit and reach (cm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Perception of pain (NRS) | ||||

| Surgical shoulder pain | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-surgical shoulder pain | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Cervical pain | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dorsal pain | 8 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Lumbar pain | 10 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Quality of life (SF-12) | ||||

| Physical | 45.92 | 47.79 | 51.59 | 51.70 |

| Mental | 59.37 | 60.57 | 59.67 | 59.53 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirandola, D.; Maestrini, F.; Carretti, G.; Manetti, M.; Marini, M. Effectiveness of an Adapted Physical Activity Protocol for Upper Extremity Recovery and Quality of Life Improvement in a Case of Seroma after Breast Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7727. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17217727

Mirandola D, Maestrini F, Carretti G, Manetti M, Marini M. Effectiveness of an Adapted Physical Activity Protocol for Upper Extremity Recovery and Quality of Life Improvement in a Case of Seroma after Breast Cancer Treatment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):7727. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17217727

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirandola, Daniela, Francesca Maestrini, Giuditta Carretti, Mirko Manetti, and Mirca Marini. 2020. "Effectiveness of an Adapted Physical Activity Protocol for Upper Extremity Recovery and Quality of Life Improvement in a Case of Seroma after Breast Cancer Treatment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 7727. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17217727