Why Do Some Spanish Nursing Students with Menstrual Pain Fail to Consult Healthcare Professionals?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample and Comparison with Excluded Participants

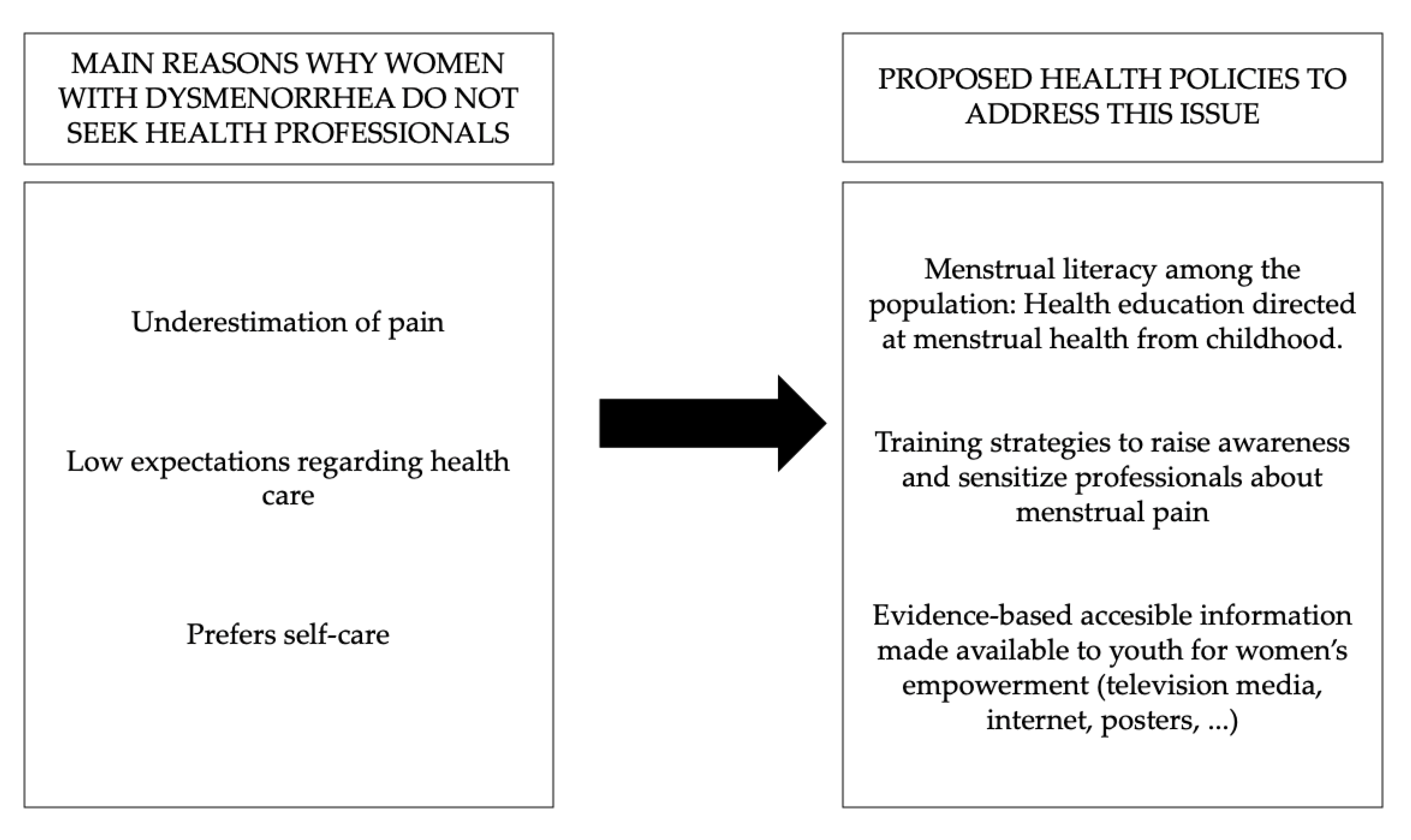

3.2. Why Do Women Fail to Consult Healthcare Professionals?

3.2.1. Underestimation of Pain

- P4 … I think it’s normal, it’s just the way it is.

- P58 … it’s part of the period.

- P176 … it’s a normal symptom of the period.

- P40 … it happens to everyone.

- P44 My whole family suffers menstrual pain and they consider it normal.

- P148 most women suffer from it.

- P37 The pain doesn’t last long.

- P95 It’s only 1 or 2 days every period and I have to deal with it.

3.2.2. Low Expectations Regarding Health Care

- P85 I don’t think it’s a good reason.

- P137 Because I don’t think it’s serious enough to go to a health clinic.

- P119 …as long as the pain is not too bad I don’t think it’s necessary to see a doctor.

- P200 It’s not serious enough for me to need to see a healthcare professional.

- P147 I went to the emergency room for the pain and they gave me an analgesic and didn’t give it any importance…

- P57 …they generally just give anti-inflammatories.

- P89 Because the most probable answer I’ll get is a hormonal contraceptive and I don’t want that kind of treatment.

- P193 They always say it’s normal; they give you analgesics and send you home.

- P8 Because it’s a bit uncomfortable.

- P36 …a doctor won’t be able to do much.

- P83 …I feel a bit ashamed that if I see a doctor they will just trivialise the problem.

- P41 I don’t have time.

- P91 I don’t have time to see a gynaecologist and getting an appointment takes forever.

3.2.3. A Preference for Self-Care

- P11 The pain is easier because I take oral contraceptives.

- P38 The pain generally goes away with an anti-inflammatory.

- P126 I mange with an analgesic.

- P202 I deal with the pain using analgesic medication.

- P37 I also use physical measures like local heat to relieve the pain.

- P108 …I need to be in bed and apply local heat for a few hours.

- P4 … it’s just the way it is.

- P65 … just put up with the pain until I can’t take it anymore.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iacovides, S.; Avidon, I.; Baker, F.C. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: A critical review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Martínez, E.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Parra-Fernández, M.L. Lifestyle and prevalence of dysmenorrhea among Spanish female university students. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Martínez, E.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Abreu-Sánchez, A.; Fernández-Muñóz, J.J.; Parra-Fernández, M.L. Absenteeism during menstruation among nursing students in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, S.-F.; Chuang, M. Factors that affect self-care behaviour of female high school students with dysmenorrhoea: A cluster sampling study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcikowska, Z.; Rajkowska-Labon, E.; Grzybowska, M.E.; Hansdorfer-Korzon, R.; Zorena, K. Inflammatory markers in dysmenorrhea and therapeutic options. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Martínez, E.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Parra-Fernández, M.L. The Impact of Dysmenorrhea on Quality of Life Among Spanish Female University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Armour, M.; Parry, K.; Manohar, N.; Holmes, K.; Ferfolja, T.; Curry, C.; MacMillan, F.; Smith, C.A. The Prevalence and Academic Impact of Dysmenorrhea in 21,573 Young Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Women’s Health 2019, 28, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoep, M.E.; Adang, E.M.M.; Maas, J.W.M.; De Bie, B.; Aarts, J.W.M.; Nieboer, T.E. Productivity loss due to menstruation-related symptoms: A nationwide cross-sectional survey among 32 748 women. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libarle, M.; Simon, P.; Bogne, V.; Pintiaux, A.; Furet, E. Management of dysmenorrhea. Rev. Med. Brux. 2018, 39, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stosic, R.; Dunagan, F.; Palmer, H.; Fowler, T.; Adams, I. Responsible self-medication: Perceived risks and benefits of over-the-counter analgesic use. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 19, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugumar, R.; Krishnaiah, V.; Channaveera, G.S.; Mruthyunjaya, S. Comparison of the pattern, efficacy, and tolerability of self-medicated drugs in primary dysmenorrhea: A questionnaire based survey. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2013, 45, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oladosu, F.A.; Tu, F.F.; Hellman, K.M. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug resistance in dysmenorrhea: Epidemiology, causes, and treatment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, M.; Smith, C.A.; Steel, K.A.; MacMillan, F. The effectiveness of self-care and lifestyle interventions in primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, M.; Parry, K.; Al-Dabbas, M.A.; Curry, C.; Holmes, K.; MacMillan, F.; Ferfolja, T.; Smith, C.A. Self-care strategies and sources of knowledge on menstruation in 12,526 young women with dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, M.; Lazzeri, L.; Perelli, F.; Reis, F.M.; Petraglia, F.; Bernardi, M.; Lazzeri, L.; Perelli, F.; Reis, F.M. Dysmenorrhea and related disorders. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osayande, A.S.; Mehulic, S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 89, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa, I.; Momoeda, M.; Osuga, Y.; Ota, I.; Koga, K. Cost-effectiveness of the recommended medical intervention for the treatment of dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in Japan. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2018, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ballard, K.; Lowton, K.; Wright, J. What’s the delay? A qualitative study of women’s experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 86, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J. The approach to chronic pelvic pain in the adolescent. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 41, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Essa, M.; Alshehri, A.; Alzahrani, M.; Bustami, R.; Adnan, S.; Alkeraidees, A.; Mudshil, A.; Gramish, J. Practices, awareness and attitudes toward self-medication of analgesics among health sciences students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, M.; Lemyre, M. Primary Dysmenorrhea Consensus Guideline. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2017, 39, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiVasta, A.D.; Vitonis, A.F.; Laufer, M.R.; Missmer, S.A. Spectrum of symptoms in women diagnosed with endometriosis during adolescence vs adulthood. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 324.e1–324.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersh, E.V.; Pinto, A.; Moore, P.A. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin. Ther. 2007, 29, 2477–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajalan, Z.; Moafi, F.; MoradiBaglooei, M.; Alimoradi, Z. Mental health and primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 40, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEGO. Gynecological history-taking and physical examination in adolescents (updated January 2013). Progresos Obstet. Ginecol. 2014, 57, 375–379. [Google Scholar]

- SEGO. Ciclo Menstrual y Visita Ginecológica. Available online: https://sego.es/mujeres/Guia del ciclo menstrual.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Chen, C.X.; Draucker, C.B.; Carpenter, J.S. What women say about their dysmenorrhea: A qualitative thematic analysis. BMC Womens Health 2018, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.X.; Shieh, C.; Draucker, C.B.; Carpenter, J.S. Reasons women do not seek health care for dysmenorrhea. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e301–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilson, E.; Haver, J.; Torondel, B.; Rubli, J.; Caruso, B.A. Dismantling menstrual taboos to overcome gender inequality. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagnik, A. Theorizing a model information pathway to mitigate the menstrual taboo. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.A.; Haththotuwa, R.; Fraser, I.S. Cultural aspects and mythologies surrounding menstruation and abnormal uterine bleeding. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 40, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente Ballesteros, S.L.; García Granja, N.; Hernández Carrasco, M.; Hidalgo Benito, A.; García Álvarez, I.; García Ramón, E. Tele-medicine consultation as a tool to improve the demand for consultation in Primary Care. Semergen 2018, 44, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez Montilla, J.M.; Sánchez Oropesa, A.; Garcés Redondo, G.; González Carnero, R.; Santos Béjar, L.; López de Castro, F. Motivos y condicionantes de la interconsulta entre atención primaria y especializada. Semergen 2013, 39, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Abreu-Sánchez, A.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D.; Iglesias-López, M.T.; Fernández-Martínez, E. Management of Primary Dysmenorrhea among University Students in the South of Spain and Family Influence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.X.; Kwekkeboom, K.L.; Ward, S.E. Beliefs About Dysmenorrhea and Their Relationship to Self-Management. Res. Nurs. Health 2016, 39, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coyne, I. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 26, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Brantelid, I.E.; Nilvér, H.; Alehagen, S. Menstruation During a Lifespan: A Qualitative Study of Women’s Experiences. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 600–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wood, J.M.; Koch, P.B.; Mansfield, P.K. Is my period normal? How college-aged women determine the normality or abnormality of their menstrual cycles. Women Health 2007, 46, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seear, K. The etiquette of endometriosis: Stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavallaee, M.; Joffres, M.R.; Corber, S.J.; Bayanzadeh, M.; Rad, M.M. The prevalence of menstrual pain and associated risk factors among Iranian women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2011, 37, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Omidvar, S.; Begum, K.B.-A. Characteristics and determinants of primary dysmenorrhea in young adults. Am. Med. J. 2012, 3, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ozerdogan, N.; Sayiner, D.; Ayranci, U.; Unsal, A.; Giray, S. Prevalence and predictors of dysmenorrhea among students at a university in Turkey. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2009, 107, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eCIE-Maps-CIE-10-ES Diagnósticos. Available online: https://eciemaps.mscbs.gob.es/ecieMaps/browser/index_10_mc_old.html (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Sánchez Galán, L.; Carbajo Sotillo, M.D. INSS Incapacidad Temporal, 4th ed.; Instituto Nacional de Seguridad Social: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.T.; Chen, Y.C. Study of menstrual attitudes and distress among postmenarcheal female students in Hualien County. J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 17, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E.; Momoeda, M.; Osuga, Y.; Rossi, B.; Nomoto, K.; Hayakawa, M.; Kokubo, K.; Wang, E.C.Y. Burden of menstrual symptoms in Japanese women—An analysis of medical care-seeking behavior from a survey-based study. Int. J. Womens. Health 2014, 6, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hansson, L.; Jormfeldt, H.; Svedberg, P.; Svensson, B. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards people with mental illness: Do they differ from attitudes held by people with mental illness? Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2013, 59, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, O.; Aroesty-Cohen, E. Attitudes of mental health professionals about mental illness: A review of the recent literature. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 38, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.M.G.; Psiquiatra, M. Aspectos subjetivos de la mujer con dismenorrea primaria. Rev. Chil. Obstet. Ginecol. 2017, 82, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SEGO. Primera Menstruación. Available online: https://sego.es/mujeres/Primera_menstruacion.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Hanson, B.; Johnstone, E.; Dorais, J.; Silver, B.; Peterson, C.M.; Hotaling, J. Female infertility, infertility-associated diagnoses, and comorbidities: A review. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2017, 34, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | Excluded Sample (Professionals Were Consulted) (n = 160) n (%)/M ± SD | Study Sample (Professionals Were not Consulted) (n = 202) n(%)/M ± SD | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22.0 ± 4.4 | 21.1 ± 2.4 | 0.031 a,* | |

| Weight (kg) | 61.0 ± 9.5 | 60.3 ± 9.5 | 0.471 | |

| Height(cm) | 164.5 ± 6.2 | 163.9 ± 6.3 | 0.400 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.6 ± 3.3 | 22.4 ± 3.3 | 0.749 | |

| Residential setting | Rural | 40 (50%) | 40 (50%) | 0.237 b |

| Urban | 120 (42.6%) | 162 (57.4%) | ||

| Worked while studying | No | 143 (44.3%) | 180 (55.7%) | 0.935 b |

| Yes | 17 (43.6%) | 22 (56.4%) | ||

| Completed the ‘women’s health’ subject | No | 69 (40.4%) | 102 (59.6%) | 0.163 b |

| Yes | 91 (47.6%) | 100 (52.4%) | ||

| Age of menarche | 12.1 ± 1.6 | 12.2 ± 1.5 | 0.814 a | |

| Regular cycle | No | 53 (50%) | 53 (50%) | 0.153 b |

| Yes | 107 (41.8%) | 149 (58.2%) | ||

| Days of bleeding | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 0.360 a | |

| Amount of flow | Low/Medium | 120 (42.1%) | 165 (57.9%) | 0.123 |

| Abundant | 40 (51.9%) | 37 (48.1%) | ||

| Cycle duration | 29.7 ± 8.8 | 29.9 ± 7.3 | 0.903 a | |

| Days of menstrual pain | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 0.001 a,* | |

| First degree relative affected | No | 67 (49.6%) | 69 (50.4%) | 0.096 b |

| Yes | 91 (40.6%) | 133 (59.4%) | ||

| Intensity of menstrual pain (VAS) | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 0.002 a,* | |

| Self-medication with analgesics | No | 47 (42.7%) | 63 (57.3%) | 0.768 b |

| Yes | 111 (44.4%) | 139 (55.6) | ||

| Consumption of contraceptives (OCPs) | No | 87 (37.2%) | 147 (62.8%) | <0.01 b,* |

| Yes | 73 (57%) | 55 (43%) | ||

| Use of non-pharmacological methods of pain relief | No | 102 (45.7%) | 121 (54.3%) | 0.504 |

| Yes | 56 (42.1%) | 77 (57.9%) | ||

| Principal Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| Underestimation of pain | It’s normal |

| It’s bearable | |

| It’s not a worry | |

| It doesn’t last long | |

| Low expectations regarding health care | It’s not a good enough reason to see a doctor |

| Disappointed expectations | |

| Lack of trust | |

| Lack of time | |

| Prefers self-care | Self-medication |

| Non-pharmacological methods | |

| Put up with the pain |

| Categories | Codes | e.g., Meaning Units |

|---|---|---|

| It’s normal | Normalisation | P13 I guess it’s normal to have pain. P32 I think it’s normal, since I’ve always had pain with my period. P85 … menstrual pain is normal and natural. |

| Known cause | P100 Because I consider that it is a pain with a known cause, and although it is annoying and sometimes intense, I don’t go to the doctor. | |

| It also happens to my family | P96 My mother, my aunt and my sister also get it. It happens to all of us, and we’ve never been to the doctor because of it. P75 Because in my family it is considered normal. | |

| It’s bearable | Bearable | P18 Because I consider it a bearable and endurable pain. P23 It’s bearable |

| Low intensity | P16 It is not a very intense pain and I don’t need to consult a doctor. P185 It is not excessive or intense pain. | |

| Not at all worrying | P21 I assumed it was because of my period and I wasn’t too worried about it. P97 It’s painful but it’s not too extreme or worrying. | |

| It’s not a worry | It’s not limiting | P138 Because it isn’t a disabling pain and does not condition my life excessively. P140 Because it doesn’t limit my ability to do things. |

| It isn’t important | P34 I haven’t given it more importance, I thought that it was simply period pain. P127 Because I don’t consider it important. | |

| It doesn’t last long | Variable duration | P161 I don’t think it’s extremely important because sometimes it lasts several days but sometimes just a few hours. |

| Short duration | P173 Because it’s only a pain that occurs just before I get my period, a short time, and I haven’t considered it important. P124 It lasts a short time. I only have it the first day and sometimes the second. |

| Categories | Codes | e.g., Meaning Units |

|---|---|---|

| It’s not a good enough reason to see a doctor | No consultation needed | P82 I don’t think it could be due to any major problem requiring me to see the doctor P113 I don’t think it’s a reason to see a doctor |

| I don’t usually go to the doctor | P2 I don’t usually go to the doctor much, and even less if it’s something unimportant like this. | |

| Disappointed expectations | Previous experiences | P147 I went to the emergency room for the pain and they gave me an analgesic and didn’t give it any importance… P198 My family doctor is never really interested in any of my problems and so I don’t bother going. |

| Predicting care | P168 Because what they are saying is that I should take birth control pills. P177 I expect they won’t think it’s important or will give me hormonal contraceptives. | |

| Lack of trust | They can’t help me | P36 …a doctor won’t be able to do much P111 A health professional is not going to change the situation much. It‘s unavoidable. |

| It’s uncomfortable/feelings of shame | P8 Because it’s a bit uncomfortable P83 …I feel a bit ashamed that if I see a doctor they will just trivialise the problem. | |

| Lack of time | I don’t have time | P55 I haven’t had time to make an appointment, although I will do so in the future. P107 I made an appointment once but I was on my way to exams. I didn’t go to the appointment and I didn’t go back for another appointment. |

| Appointment delays | P28 It takes so long to get an appointment that it’s not worth asking. P170 If you ask for an appointment, when they give it to you the pain has already gone away. |

| Categories | Codes | e.g., Meaning Units |

|---|---|---|

| Self-medication | Self-medication using hormonal contraceptives | P11 The pain is more bearable because I take oral contraceptives. P66 I usually take oral contraceptives and that works well for me. |

| Self-medication using analgesics | P42 I can deal with it if I take 1 or 2 Naproxen. P65 I usually take ibuprofen… P202 I deal with the pain thanks to analgesic medication. | |

| Non-pharmacological methods | Local heat | P56 …I apply heat to the area and that relieves the pain. P108 …I need to be in bed and apply local heat for a few hours. |

| Enduring the pain | Endure the pain | P105 I ‘ve always thought that menstrual pain must be endured. P122 That’s the way it is, you have to suffer it every month. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos-Pichardo, J.D.; Ortega-Galán, Á.M.; Iglesias-López, M.T.; Abreu-Sánchez, A.; Fernández-Martínez, E. Why Do Some Spanish Nursing Students with Menstrual Pain Fail to Consult Healthcare Professionals? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8173. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17218173

Ramos-Pichardo JD, Ortega-Galán ÁM, Iglesias-López MT, Abreu-Sánchez A, Fernández-Martínez E. Why Do Some Spanish Nursing Students with Menstrual Pain Fail to Consult Healthcare Professionals? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):8173. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17218173

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos-Pichardo, Juan Diego, Ángela María Ortega-Galán, María Teresa Iglesias-López, Ana Abreu-Sánchez, and Elia Fernández-Martínez. 2020. "Why Do Some Spanish Nursing Students with Menstrual Pain Fail to Consult Healthcare Professionals?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 8173. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17218173