Teachers’ Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Thwarting: Can They Explain Students’ Behavioural Engagement in Physical Education? A Multi-Level Analysis

Abstract

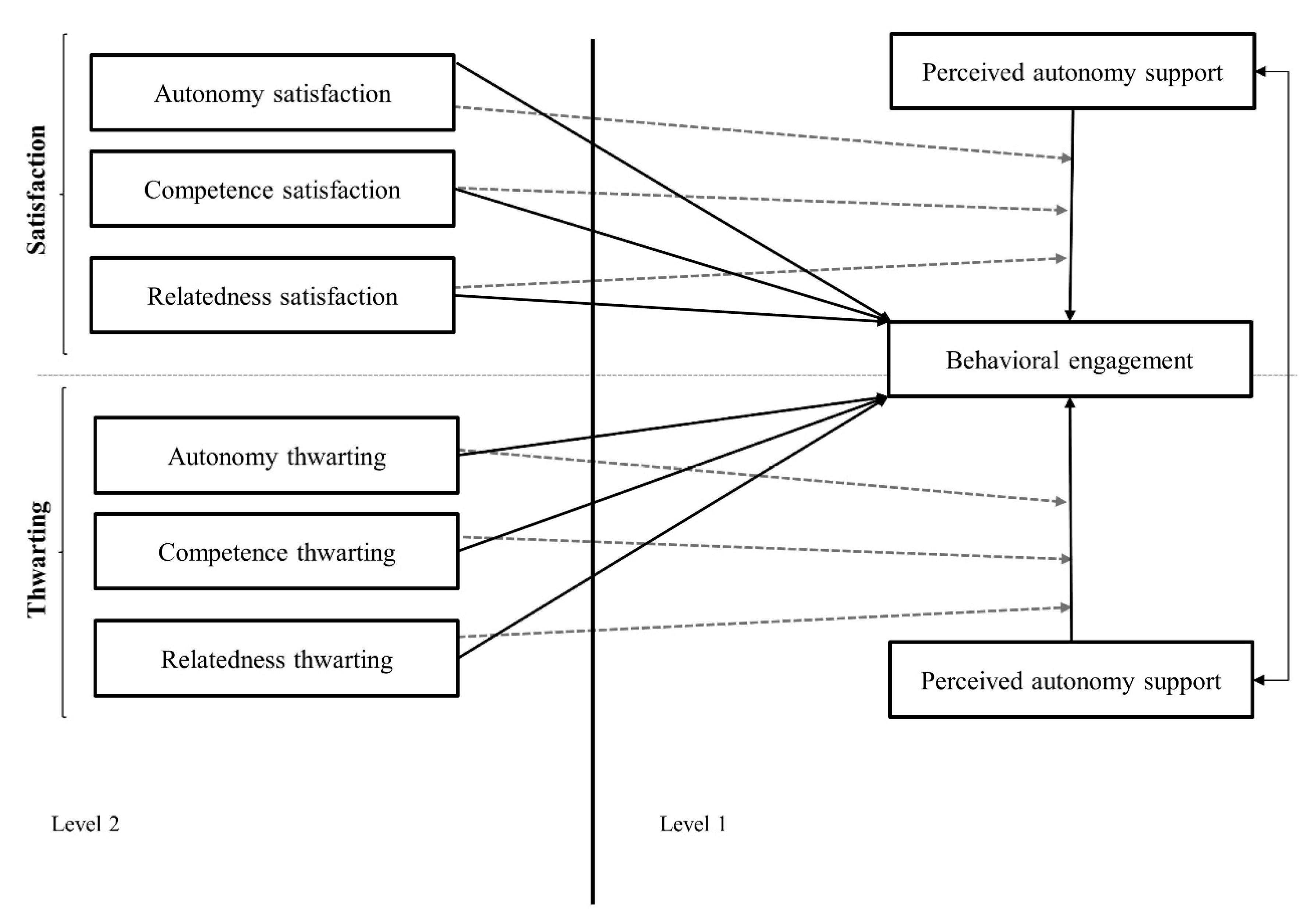

:1. Introduction

1.1. Engagement in PE

1.2. Teachers’ Provision of Autonomy Support in PE

1.3. Teachers’ Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Thwarting

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Teachers’ Basic Needs Satisfaction

2.2.2. Teachers’ Basic Needs Thwarting

2.2.3. Students’ Behavioural Engagement

2.2.4. Students’ Perceived Autonomy Support

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Prediction of Students’ Engagement through BPN Satisfaction

3.2.1. Null Model

3.2.2. Random Intercepts Model

3.2.3. Intercepts- and Slopes-as-Outcomes Model

3.3. Prediction of Students’ Engagement through BPN Thwarting

Intercepts- and Slopes-as-Outcomes Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, A.; Schweighardt, R.; Zhang, T.; Wells, S.; Ennis, C. The nature of learning tasks and knowledge acquisition: The role of cognitive engagement in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, E.; Furrer, C.; Marchand, G.; Kinderman, T. Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations:Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, A.D.; Smedegaard, S.; Pawloski, C.S.; Skovgaard, T.; Christiansen, L.B. Pupils’ experiences of autonomy, competence and relatedness in “Move for well-being in schools”: A physical activity intervention. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2018, 25, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. Perceived autonomy support and behavioral engagement in physical education: A conditional process model of positive emotion and autonomous motivation. Percept. Mot. Ski. Exerc. Sport 2015, 120, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. Autonomy-Supportive Teaching: What it is, How to Do it. In Building Autonomous Learners; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, J.; Cheon, S.H. Teachers become more autonomy supportive after they believe it is easy to do. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 22, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berghe, L.; Soenens, B.; Aelterman, N.; Cardon, G.; Tallir, I.B.; Haerens, L. Within-person profiles of teachers’ motivation to teach: Associations with need satisfaction at work, need-supportive teaching, and burnout. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matosic, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; Quested, E. Antecedents of Need Supportive and Controlling Interpersonal Styles from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective: A Review and Implications for Sport Psychology Research. In Sport and Exercise Psychology Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 145–180. [Google Scholar]

- Abós, A.; Haerens, L.; Sevil, J.; Aelterman, N.; García-González, L. Teachers’ motivation in relation to their psychological functioning and interpersonal style: A variable- and person-centered approach. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 74, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J. Why autonomy-supportive interventions work: Explaining the professional development of teachers’ motivating style. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 69, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, I.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Standage, M. A self-determination theory approach to understanding the antecedents of teachers’ motivational strategies in physical education. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Korthagen, F.A.J.; Evelein, F.G. Relations between student teachers’ basic needs fulfillment and their teaching behavior. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 60, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Cuevas, R.; Lonsdale, C. Job pressure and ill-health in physical education teachers: The mediating role of psychological need thwarting. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 37, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stebbings, J.; Taylor, I.M.; Spray, C.; Ntoumanis, N. Antedecents of perceived coach interpersonal behaviors: The coaching environment and coach psychological well- and ill-being. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Curran, T.; Standage, M. Psychological needs and the quality of student engagement in Physical Education: Teachers as key facilitators. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D. Physical education, youth sport and lifelong participation: The importance of early learning experiences. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2005, 11, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.N.; Wu, W.; West, S.G. Teacher performance goal practices and elementary students’ behavioral engagement: A developmental perspective. J. Sch. Psychol. 2011, 49, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skinner, E.A.; Pitzer, J.R. Developmental Dynamics of Student Engagement, Coping, and Everyday Resilience. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- González, A.; Paoloni, P.; Donolo, D.; Rinaudo, C. Behavioral engagement and disaffection in school activities: Exploring a model of motivational facilitators and performance outcomes. An. Psicol. 2015, 31, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hospel, V.; Galand, B.; Janosz, M. Multidimensionality of behavioural engagement: Empirical support and implications. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 77, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J.J.; Christenson, S.L.; Furlong, M.J. Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychol. Sch. 2008, 45, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, I.; Janosz, M.; Fallu, J.-S.; Pagani, L.S. Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, H.M. Student Engagement in Instructional Activity: Patterns in the Elementary, Middle, and High School Years. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 37, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Lens, W.; Sideridis, G. The motivating role of positive feedback in sport and physical education: Evidence for a motivational model. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 240–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van den Berghe, L.; Cardon, G.; Tallir, I.B.; Kirk, D.; Haerens, L. Dynamics of need-supportive and need-thwarting teaching behavior: The bidirectional relationship with student engagement and disengagement in the beginning of a lesson. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Uden, J.M.; Ritzen, H.; Pieters, J.M. I think I can engage my students. Teachers’ perceptions of student engagement and their beliefs about being a teacher. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 32, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leptokaridou, E.T.; Vlachopoulos, S.P.; Papaioannou, A. Experimental longitudinal test of the influence of autonomy-supportive teaching on motivation for participation in elementary school physical education. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 36, 1138–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.L.; Sung, H.C.; Williams, J.D. The defining features of teacher talk within autonomy-supportive classroom management. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 42, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Moon, I.S. Experimentally based, longitudinally designed, teacher-focused intervention to help physical education teachers be more autonomy supportive toward their students. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.H. Emotional labor, teacher burnout, and turnover intention in high-school physical education teaching. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.; Andrew, K.; Washburn, N.S.; Hemphill, M.A. Exploring the influence of perceived mattering, role stress, and emotional exhaustion on physical education teacher/coach job satisfaction. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Assor, A.; Ahmad, I.; Cheon, S.H.; Jang, H.; Kaplan, H.; Moss, J.D.; Olaussen, B.S.; Wang, J.C.K. The beliefs that underlie autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching: A multinational investigation. Motiv. Emot. 2014, 38, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.; Sharp, E. Administrative pressures and teachers’ interpersonal behaviour in the classroom. Theory Res. Educ. 2009, 7, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, I.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Smith, B. The context as a determinant of teacher motivational strategies im physical education. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Berghe, L.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Aelterman, N.; Cardon, G.; Tallir, I.B.; Haerens, L. Observed need-supportive and need-thwarting teaching behavior in physical education: Do teachers’ motivational orientations matter? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Gagné, M.; Leone, D.; Usunov, J.; Kornazheva, B.P. Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural sudy of self-determination. PSPB 2001, 27, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carson, R.L.; Chase, M.A. An examination of physical education teacher motivation from a self-determination theoretical framework. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2009, 14, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Self-determination theory and the darker side of athletic experience: The role of interpersonal control and need thwarting. Sport Exerc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 7, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Pulido, J.J.; López-Chamorro, J.M.; Cuevas, R. Motivation y burnout en profesores de educación física: Incidencia de la frustración de las necesidades psicológicas básicas. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2014, 14, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (Amended August 3, 2016); American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Questionnaires: Basic Psychological Needs Scale. Available online: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/basic-psychological-needs-scale/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Cuevas, R.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; García-Calvo, T. Adaptation and validation of the psychological need thwarting scale in Spanish Physical Education teachers. Span. J. Psychol. 2015, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Psychological need thwarting in the sport context: Assessing the darker side of athletic experience. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 33, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shen, B.; McCaughtry, N.; Martin, J.; Fahlman, M.; Garn, A. Urban high-school girls’ sense of relatedness and their engagement in Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2012, 31, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiz, M. Soporte de Autonomía y Motivación en Educación. Consecuencias a Nivel Contextual y Global. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Miguel Hernández, Elche, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Röder, B.; Kleine, D. Selbstbesstimmung/Autonomie. In Förderung von Selbstwirksamkeitund Selbstbestimmungim Unterricht; Jerusalem, M., Drössler, S., Kleine, D., Klein-HeBling, J., Mittag, W., Röder, B., Eds.; Hummboldt-Universitätzu Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bechter, B.E.; Dimmock, J.A.; Howard, J.L.; Whipp, P.R.; Jackson, B. Student Motivation in High School Physical Education: A Latent Profile Analysis Approach. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 40, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hospel, V.; Galand, B. Are both classroom autonomy support and structure equally important for students’ engagement? A multilevel analysis. Learn. Instr. 2016, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, K.; Simmons, P. Exploring the use of effect sizes to evaluate the impact of different influences on child outcomes: Possibilities and limitations. In But What Does It Mean? The Use of Effect Sizes in Educational Research; Schagen, I., Elliot, K., Eds.; National Foundation for Educational Research: Berks, UK, 2004; pp. 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, F.; Gray, S.; Inchley, J. “This choice thing really works…” Changes in experiences and engagement of adolescent girls in physical education classes, during a school-based physical activity programme. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2015, 20, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Jang, H.; Carrell, D.; Jeon, S.; Barch, J. Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motiv. Emot. 2004, 28, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, V. Perceived autonomy support and behavioral engagement: Comment on Yoo (2015). Percept. Mot. Ski. 2016, 123, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Ntoumanis, N. A needs-supportive intervention to help PE teachers enhance students’ prosocial behavior and diminish antisocial behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 35, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Song, Y. A teacher-focused intervention to decrease PE students’ amotivation by increasing need satisfaction and decreasing need frustration. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Van Keer, H.; Haerens, L. Changing teachers’ beliefs regarding autonomy support and structure: The role of experienced psychological need satisfaction in teacher training. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 23, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Witte, H.; Soenens, B.; Lens, W. Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: Construction and initial validation of the work-related Basic Need Satisfaction scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cordeiro, P.; Paixão, P.; Lens, W.; Lacante, M.; Sheldon, K. Factor structure and dimensionality of the balanced measure of psychological needs among portuguese high school students. Relations to well-being and ill-being. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 47, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, Y.; Alcaraz-Ibáñez, M.; Sicilia, A. Evidence supporting need satisfaction and frustration as two distinguishable constructs. Psicothema 2018, 30, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 2013, 23, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Bosch, J.A.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C. Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klassen, R.M.; Perry, N.E.; Frenzel, A.C. Teachers’ relatedness with students: An underemphasized component of teachers’ basic psychological needs. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. Motivational Factors Influencing Teaching as a Career Choice: Development and Validation of the FIT-Choice Scale. J. Exp. Educ. 2007, 75, 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-López, P.; Almagro, B.J.; Ibáñez, S.J. Describing problems experienced by spanish novice physical education teachers. Open Sports Sci. J. 2011, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, B.; Aelterman, N.; Beyers, W.; Aper, L.; Buysschaert, F.; Vansteenkiste, M. The role of teachers’ motivation and mindsets in predicting a (de)motivating teaching style in higher education: A circumplex approach. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 270–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Autonomy satisfaction | ||||||||

| 2. Competence satisfaction | 0.45 ** | |||||||

| 3. Relatedness satisfaction | 0.49 ** | 0.46 ** | ||||||

| 4. Autonomy thwarting | −0.53 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.24 ** | |||||

| 5. Competence thwarting | −0.43 ** | −0.51 ** | −0.28 ** | 0.61 ** | ||||

| 6. Relatedness thwarting | −0.36 ** | −0.55 ** | −0.39 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.56 ** | |||

| 7. Engagement | 0.29 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.48 ** | −0.40 ** | −0.31 ** | ||

| 8. Students’ autonomy support | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.28 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.07 | 0.27 ** | |

| Possible range | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–5 | 1–5 |

| M | 4.01 | 4.11 | 3.76 | 2.36 | 2.03 | 1.87 | 4.21 | 3.01 |

| SD | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 1.47 | 1.34 | 1.10 | 0.65 | 1.04 |

| Parameter | Null Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed part | |||||

| Intercept | 4.19 (0.07) | 4.19 (0.07) | 4.19 (0.06) | ||

| Student level variables (level1) | |||||

| PAS | 0.08 (0.03) ** | 0.08 (0.02) ** | 0.017 | ||

| Teacher level variables (level2) | |||||

| Autonomy satisfaction | 0.33 (0.14) * | 0.318 | |||

| Competence satisfaction | 0.12 (0.12) | ||||

| Relatedness satisfaction | −0.01 (0.16) | ||||

| Interaction | |||||

| Autonomy satisfaction * slope | 0.02 (0.05) | ||||

| Competence satisfaction * slope | −0.05 (0.05) | ||||

| Relatedness satisfaction * slope | 0.02 (0.07) | ||||

| Random part | |||||

| Teacher-level variance | 0.37 (0.14) | 0.37 (0.14) | 0.32 (0.10) | ||

| Student-level variance | 0.55 (0.30) | 0.54 (0.29) | 0.54 (0.29) | ||

| Model fit | |||||

| Deviance | 1117.54 | 1114.83 | 1093.42 | ||

| χ2/df | 2.71 (2) | 21.41 (8) ** |

| Parameter | Null Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed part | |||||

| Intercept | 4.19 (0.07) | 4.19 (0.07) | 4.19 (0.03) | ||

| Student level variables (level1) | |||||

| PAS | 0.08 (0.03) ** | 0.10 (0.02) ** | 0.014 | ||

| Teacher level variables (level2) | |||||

| Autonomy thwarting | −0.17 (0.03) *** | 0.036 | |||

| Competence thwarting | −0.06 (0.03) * | 0.012 | |||

| Relatedness thwarting | −0.03 (0.03) | ||||

| Interaction | |||||

| Autonomy thwarting * slope | −0.02 (0.02) | ||||

| Competence thwarting * slope | 0.04 (0.03) | ||||

| Relatedness thwarting * slope | 0.02 (0.03) | ||||

| Random part | |||||

| Teacher-level variance | 0.37 (0.14) | 0.37 (0.14) | 0.11 (0.02) | ||

| Student-level variance | 0.55 (0.30) | 0.54 (0.29) | 0.54 (0.29) | ||

| Model fit | |||||

| Deviance | 1117.54 | 1114.83 | 1053.71 | ||

| χ2/df | 2.71 (2) | 61.12 (8) *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coterón, J.; Franco, E.; Ocete, C.; Pérez-Tejero, J. Teachers’ Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Thwarting: Can They Explain Students’ Behavioural Engagement in Physical Education? A Multi-Level Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8573. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17228573

Coterón J, Franco E, Ocete C, Pérez-Tejero J. Teachers’ Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Thwarting: Can They Explain Students’ Behavioural Engagement in Physical Education? A Multi-Level Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8573. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17228573

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoterón, Javier, Evelia Franco, Carmen Ocete, and Javier Pérez-Tejero. 2020. "Teachers’ Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Thwarting: Can They Explain Students’ Behavioural Engagement in Physical Education? A Multi-Level Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8573. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17228573