How Can Job Crafting Be Reproduced? Examining the Trickle-Down Effect of Job Crafting from Leaders to Employees

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Job Crafting

2.2. Trickle-Down Effect of Job Crafting: From Team Leaders to Team Members

2.3. Mediating Effect of Leaders’ Job Resources

2.4. The Moderating Role of Empowering Leadership

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

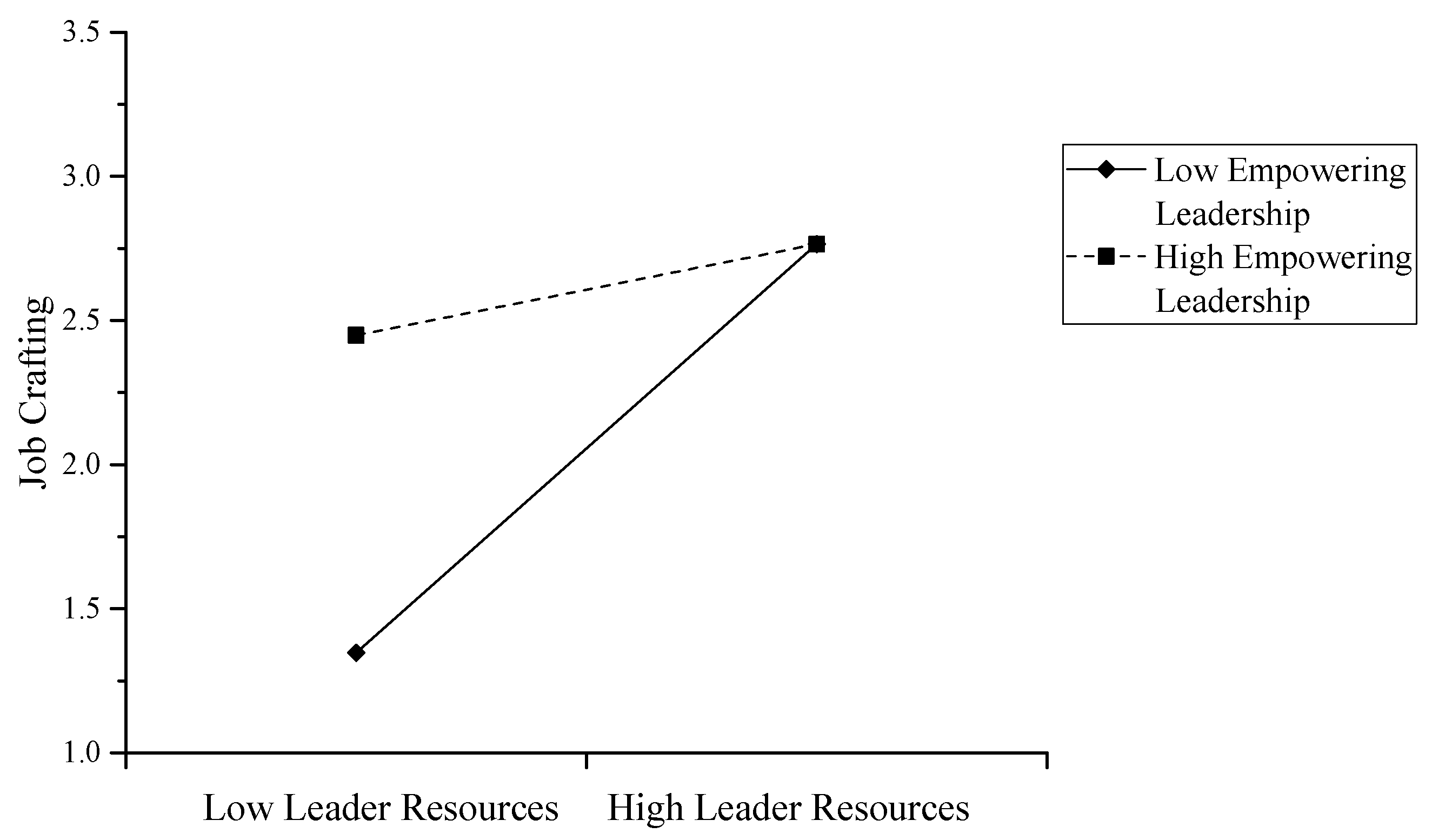

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berg, J.M.; Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazazzara, A.; Tims, M.; De Gennaro, D. The process of reinventing a job: A meta–synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 116, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D.; Van Rhenen, W. Job crafting at the team and individual level: Implications for work engagement and performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, L.K.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hakanen, J.J. A multilevel study on servant leadership, job boredom and job crafting. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, R.; Ming, Y.; Ma, J.; Huo, R. How do servant leaders promote engagement? A bottom-up perspective of job crafting. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2017, 45, 1815–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierdorff, E.C.; Jensen, J.M. Crafting in context: Exploring when job crafting is dysfunctional for performance effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1766–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.-J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xie, B.; Guo, Y. The trickle-down of work engagement from leader to follower: The roles of optimism and self-efficacy. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.; Ruiz, C.; Martínez, R. Improving the “leader–follower” relationship: Top manager or supervisor? The ethical leadership trickle-down effect on follower job response. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 587–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawritz, M.B.; Mayer, D.M.; Hoobler, J.M.; Wayne, S.J.; Marinova, S.V. A trickle-down model of abusive supervision. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 325–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Sotial Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Beehr, T.A. Can empowering leaders affect subordinates’ well-being and careers because they encourage subordinates’ job crafting behaviors? J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Social-learning theory of identificatory processes. Handb. Social. Theory Res. 1969, 213, 262. [Google Scholar]

- Wo, D.X.; Ambrose, M.L.; Schminke, M. What drives trickle-down effects? A test of multiple mediation processes. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1848–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghitulescu, B.E. Shaping Tasks and Relationships at Work: Examining the Antecedents and Consequences of Employee Job Crafting; University of Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Derks, D. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Dutton, J.E.; Wrzesniewski, A. What is job crafting and why does it matter. Posit. Organ. Scholarsh. 2008, 15, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. Design your own job through job crafting. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Parker, S.K. 7 redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 317–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.; Appelbaum, E.; Shevchuk, I. Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H.J. How to build your team for innovation? A cross-level mediation model of team personality, team climate for innovation, creativity, and job crafting. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 92, 842–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.; Lepsinger, R. Flexible Leadership: Creating Value by Balancing Multiple Challenges and Choices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 223. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, H.M. Subordinate imitation of supervisor behavior: The role of modeling in organizational socialization. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1977, 19, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.G.; Cheol Gang, M. Managers as a Missing Entity in Job Crafting Research: Relationships between Store Manager Job Crafting, Job Resources, and Store Performance. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. Psychol. Appl. Rev. Int. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.; Bardes, M.; Salvador, R.B. How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 108, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somech, A.; Ohayon, B.-E. The trickle-down effect of OCB in schools: The link between leader OCB and team OCB. J. Educ. Adm. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job crafting in changing organizations: Antecedents and implications for exhaustion and performance. J. Occup. Health Psych. 2015, 20, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voydanoff, P. The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. J. Marriage Fam. 2004, 66, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, S.W.; Bell, B.S. Work groups and teams in organizations. Handb. Psychol. 2003, 333–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, J.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Teng, H.-Y.; Yen, C.-H. Tour leaders’ job crafting and job outcomes: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Aunola, K.; Seppälä, P.; Hakanen, J. Work engagement–team performance relationship: Shared job crafting as a moderator. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 772–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Mathieu, J.; Rapp, A. To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amundsen, S.; Martinsen, Ø.L. Empowering leadership: Construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, J.A.; Arad, S.; Rhoades, J.A.; Drasgow, F. The empowering leadership questionnaire: The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring leader behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Silver, S.R.; Randolph, W.A. Taking empowerment to the next level: A multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 332–349. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, T.; Pelled, L.H.; Smith, K.A. Making use of difference: Diversity, debate, and decision comprehensiveness in top management teams. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 662–673. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology 1980, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Laurence, G.A. Workaholism and Expansion and Contraction Oriented Job Crafting: The Moderating Effects of Individual and Contextual Factors; Syracuse University: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R. Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. In Health Work; Basic Books Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. The transformation of professionals into self-managing and partially self-designing contributors: Toward a theory of leadership-making. J. Manag. Syst. 1991, 3, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.; Bartol, K.M.; Locke, E.A. Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi, D.; MacKinnon, D.P. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behav. Res. Methods 2011, 43, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fritz, M.S.; Williams, J.; Lockwood, C.M. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thun, S.; Bakker, A.B. Empowering leadership and job crafting: The role of employee optimism. Stress Health 2018, 34, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. A review of job-crafting research: The role of leader behaviors in cultivating successful job crafters. In Proactivity at Work; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Waybe, S.J.; Hoobler, J.; Marinova, S.V.; Johnson, M.M. Abusive Behavior: Trickle-Down Effects beyond the Dyad; Academy of Management Proceedings, Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor: Westchester County, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers; Cartwright, D., Ed.; Harper: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Derks, D. Who takes the lead? A multi-source diary study on leadership, work engagement, and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Liao, H.; Raub, S.; Han, J.H. What it takes to get proactive: An integrative multilevel model of the antecedents of personal initiative. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerr, S.; Jermier, J.M. Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1978, 22, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Sharma, P.N.; Edinger, S.K.; Shapiro, D.L.; Farh, J.-L. Motivating and demotivating forces in teams: Cross-level influences of empowering leadership and relationship conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, D.J.; Wall, T.D.; Jackson, P.R. The effect of empowerment on job knowledge: An empirical test involving operators of complex technology. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, W.; Han, Y.; Zhang, P. Linking empowering leadership and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: The role of thriving at work and autonomy orientation. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2016, 29, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.L.; Liao, H.; Campbell, E.M. Directive versus empowering leadership: A field experiment comparing impacts on task proficiency and proactivity. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1372–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level | |||||||

| 1. Age | 29.95 | 7.04 | |||||

| 2. Gender | 1.36 | 0.48 | 0.18 * | ||||

| 3. Education | 3.70 | 0.78 | −0.03 | 0.14 * | |||

| 4. Tenure | 5.84 | 7.26 | 0.86 *** | 0.14 * | −0.13 | ||

| 5. Team members’ job crafting | 2.34 | 0.69 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.91 |

| Team-level | |||||||

| 1. Leaders’ job crafting | 2.50 | 0.60 | 0.92 | ||||

| 2. Leaders’ job resource | 3.80 | 0.51 | 0.55 *** | 0.89 | |||

| 3. Empowering leadership | 4.68 | 0.49 | 0.37 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.92 |

| Variables | Leader’s Job Resource | Team Employees’ Job Crafting | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Intercept (γ00) | 1.99 *** | 2.24 *** | 1.45 ** | 0.29 | 1.76 *** |

| Level 1 control variables | |||||

| Gender (γ10) | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.06 | |

| Age (γ20) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.01 | |

| Tenure (γ30) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Education (γ40) | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | |

| Level 2 independent variables | |||||

| Leaders’ Job Crafting (γ01) | 0.44 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.24 * | 0.25 * | |

| Empowering Leadership (γ02) | 0.30 *** | ||||

| Level 2 mediated variables | |||||

| Leaders’ Job Resource (γ03) | 0.35 *** | 0.26 * | |||

| Level 2 Cross-level interactions | |||||

| Empowering Leadership × Leaders’ Job Resource (γ06) | −0.21 * | ||||

| Moderator Variable Empowering Leadership | Stage | Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Direct | Indirect | Total | |

| Low (−1 s.d.) | 0.45 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.23 ** | 0.21 *** | 0.46 *** |

| High (1 s.d.) | 0.45 *** | 0.21 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.10 | 0.34 *** |

| Differences between low and high | 0.00 | –0.26 † | 0.00 | –0.11 * | –0.11 * |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xin, X.; Cai, W.; Zhou, W.; Baroudi, S.E.; Khapova, S.N. How Can Job Crafting Be Reproduced? Examining the Trickle-Down Effect of Job Crafting from Leaders to Employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 894. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17030894

Xin X, Cai W, Zhou W, Baroudi SE, Khapova SN. How Can Job Crafting Be Reproduced? Examining the Trickle-Down Effect of Job Crafting from Leaders to Employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):894. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17030894

Chicago/Turabian StyleXin, Xun, Wenjing Cai, Wenxia Zhou, Sabrine El Baroudi, and Svetlana N. Khapova. 2020. "How Can Job Crafting Be Reproduced? Examining the Trickle-Down Effect of Job Crafting from Leaders to Employees" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 894. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17030894