The Relationship between Frailty Syndrome and Concerns about an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

2.2. Study Participants and Selection

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Research Instruments

3. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Study limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bandeen-Roche, K.; Xue, Q.; Ferrucci, L.; Walston, J.; Guralnik, J.M.; Chaves, P.; Zeger, S.L.; Fried, L.P. Phenotype of frailty: Characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fried, L.; Tangen, C.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, T.; Gahbauer, E.; Allore, H.; Han, L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.; Snih, S.; Berges, I.; Ray, L.; Markides, K.S.; Ottenbacher, K.J. Frailty and 10-year mortality in community-living Mexican American older adults. Gerontology 2009, 55, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensrud, K.; Ewing, S.; Cawthon, P.; Fink, H.A.; Taylor, B.C.; Cauley, J.A.; Dam, T.T.; Marshall, L.M.; Orwoll, E.S.; Cummings, S.R.; et al. A comparison of frailty indexes for the prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and mortality in older men. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, M.; Orkaby, A.; Rosenberg, M.; Driver, J.A. Frailty, implantable cardioverter defibrillators, and mortality: A systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 2224–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibas, L.; Levi, M.; Touchette, J.; Mardigyan, V.; Bernier, M.; Essebag, V.; Afilalo, J. Implications of frailty in elderly patients with electrophysiological conditions. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2016, 2, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frizelle, D.; Lewin, B.; Kaye, G.; Moniz-Cook, E.D. Development of a measure of the concerns held by people with implanted cardioverter defibrillators: The ICDC. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchmanowicz, I.; Gobbens, R.; Jankowska-Polanska, B.; Łoboz-Rudnicka, M.; Manulik, S.; Łoboz-Grudzień, K. Cross-Cultural adaptation and reliability testing of the Tilburg frailty indicator for optimizing care of Polish patients with frailty syndrome. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gobbens, R.; van Assen, M.; Luijkx, K.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M.T.; Schols, J.M.G.A. The Tilburg frailty indicator: Psychometric properties. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2010, 11, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santulli, G.; Pascale, V.; Finelli, R.; Visco, V.; Giannotti, R.; Massari, A.; Morisco, C.; Ciccarelli, M.; Illario, M.; Iaccarino, G.; et al. We are what we eat: Impact of food from short supply chain on metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pedersen, S.; van Domburg, R.; Theuns, D.; Jordaens, L.; Erdman, R.A. Concerns about the implantable cardioverter defibrillator: A determinant of anxiety and depressive symptoms independent of experienced shocks. Am. Heart J. 2005, 149, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, S.; Shea, J.; Conti, J. How to respond to an implantable cardioverter defibrillator shock. Circulation 2005, 111, e380–e382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohamed, M.; Sharma, P.; Volgman, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kwok, C.S.; Rashid, M.; Barker, D.; Patwala, A.; Mamas, M.A. Prevalence, outcomes, and costs according to patient frailty status for 2.9 million cardiac electronic device implantations in the United States. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, D.; Tsai, T.; Natarajan, P.; Tewksbury, E.; Mitchell, S.L.; Travison, T.G. Frailty, physical activity, and mobility in patients with cardiac implantable electrical devices. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frizelle, D.; Lewin, R.; Kaye, G.; Hargreaves, C.; Hasney, K.; Beaumont, N.; Moniz-Cook, E. Cognitive-Behavioural rehabilitation programme for patients with an implanted cardioverter defibrillator: A pilot study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, S.; Van den Berg, M.; Erdman, R.; VAN Son, J.; Jordaens, L.; Theuns, D.A. Increased anxiety in partners of patients with a cardioverter-defibrillator: The role of indication for ICD therapy, shocks, and personality. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2009, 32, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, J.; Mortensen, P.; Videbæk, R.; Riahi, S.; Møller, M.; Haarbo, J.; Pedersen, S.S. Attitudes towards implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy: A national survey in Danish health-care professionals. Europace 2011, 13, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, N.; Carlson, M.; Livote, E.; Kutner, J. Brief communication: Management of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in hospice: A nationwide survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.; Leff, B.; Wang, Y.; Spatz, E.S.; Masoudi, F.A.; Peterson, P.N.; Daugherty, S.L.; Matlock, D.D. Geriatric conditions in patients undergoing defibrillator implantation for prevention of sudden cardiac death: Prevalence and impact on mortality. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2016, 9, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Parameter | All | Frail | Robust | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 71.56 ± 8.17 | 71.67 ± 8.40 | 71.24 ± 7.54 | 0.562 |

| Weight | 80.89 ± 17.61 | 79.01 ± 18.13 | 86.28 ± 15.19 | 0.386 |

| BMI | 28.80 ± 4.72 | 28.04 ± 4.83 | 30.25 ± 4.49 | 0.748 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| City area | 81.55% | 79.49% | 88% | 0.339 |

| Rural area | 18.45% | 20.51% | 12% | |

| Education | ||||

| Non or primary | 37.87% | 61.54% | 56% | 0.693 |

| Secondary | 61.16% | 1.28% | 4% | |

| Vocational or higher | 0.97% | 37.18% | 40% | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married/living with partner | 89.32% | 88.46% | 92% | 0.683 |

| Unmarried | 7.77% | 8.97% | 4% | |

| Widow/widower | 2.91% | 2.56% | 4% | |

| Professional status | ||||

| Working | 21.36% | 19.23% | 28% | 0.568 |

| Retired | 71.84% | 73.08% | 68% | |

| Pensioner | 6.80% | 7.69% | 4% | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Smoker | 29.13% | 44% | 24.36% | 0.059 |

| Number | Question I Am Worried About: | Not at all n (%) | A little Bit n (%) | Somewhat n (%) | Quite a Lot n (%) | Very Much So n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | My ICD firing | 21 (20.39%) | 52 (50.48%) | 27 (26.21%) | 3 (2.91%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2. | My ICD not working when I need it to | 26 (25.24%) | 55 (53.40%) | 18 (17.47%) | 4 (3.88%) | 0 (0%) |

| 3. | What I should do if my ICD fires | 29 (28.16%) | 46 (44.66%) | 26 (25.24%) | 2 (1.94%) | 0 (0%) |

| 4. | Doing exercise in case it causes my ICD to fire | 29 (28.16%) | 42 (40.78%) | 29 (28.16%) | 3 (2.91%) | 0 (0%) |

| 5. | Doing activities/hobbies that may cause my ICD to fire | 28 (27.18%) | 45 (43.69%) | 26 (25.24%) | 4 (3.88%) | 0 (0%) |

| 6. | My heart condition getting worse if the ICD fires | 27 (26.21%) | 40 (38.83%) | 32 (31.07%) | 4 (3.88%) | 0 (0%) |

| 7. | The amount of time I spend thinking about my heart condition and having an ICD | 33 (32.04%) | 43 (41.75%) | 26 (25.24%) | 1 (0.97%) | 0 (0%) |

| 8. | The amount of time I spend thinking about my ICD firing | 32 (31.07%) | 40 (38.83%) | 28 (27.18%) | 3 (2.91%) | 0 (0%) |

| 9. | The ICD battery running out | 27 (26.21%) | 41 (39.81%) | 25 (24.27%) | 10 (0.97%) | 0 (0%) |

| 10. | Working too hard/overdoing things and causing my ICD to fire | 30 (29.13%) | 41 (39.81%) | 29 (28.16%) | 3 (2.91%) | 0 (0%) |

| 11. | Making love in case my ICD fires | 34 (33.01%) | 44 (42.72%) | 21 (20.39%) | 4 (3.88%) | 0 (0%) |

| 12. | Having no warning that my ICD will fire | 26 (25.24%) | 36 (34.95%) | 36 (34.95%) | 5 (4.85%) | 0 (0%) |

| 13. | The symptoms/pain associated with my ICD firing | 24 (23.30%) | 45 (43.69%) | 31 (30.09%) | 3 (2.92%) | 0 (0%) |

| 14. | Being a burden on my partner/family | 48 (46.60%) | 35 (33.98%) | 16 (15.53%) | 4 (3.88%) | 0 (0%) |

| 15. | Not being able to prevent my ICD from firing | 27 (26.21%) | 45 (43.69%) | 26 (25.24%) | 4 (3.88%) | 1 (0.97%) |

| 16. | The future now that I have an ICD | 22 (21.36%) | 48 (46.60%) | 30 (29.13%) | 3 (2.91%) | 0 (0%) |

| 17. | Problems occurring with my ICD, e.g., battery failure | 31 (30.09%) | 42 (40.77%) | 25 (24.27%) | 5 (4.85%) | 0 (0%) |

| 18. | Getting too stressed in case my ICD fires | 29 (28.16%) | 54 (52.43%) | 18 (17.47%) | 2 (1.94%) | 0 (0%) |

| 19. | Not being able to work/take part in activities and hobbies because I have an ICD | 46 (44.66%) | 31 (30.09%) | 22 (21.36%) | 4 (3.88%) | 0 (0%) |

| 20. | Exercising too hard and causing my ICD to fire | 56 (54.37%) | 35 (33.98%) | 11 (10.68%) | 1 (0.97%) | 0 (0%) |

| Parameter | Frail | Robust | All | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total questionnaire score | 36.14 ± 17.08 | 27.56 ± 20.13 | 34.06 ± 18.15 | 0.039035 |

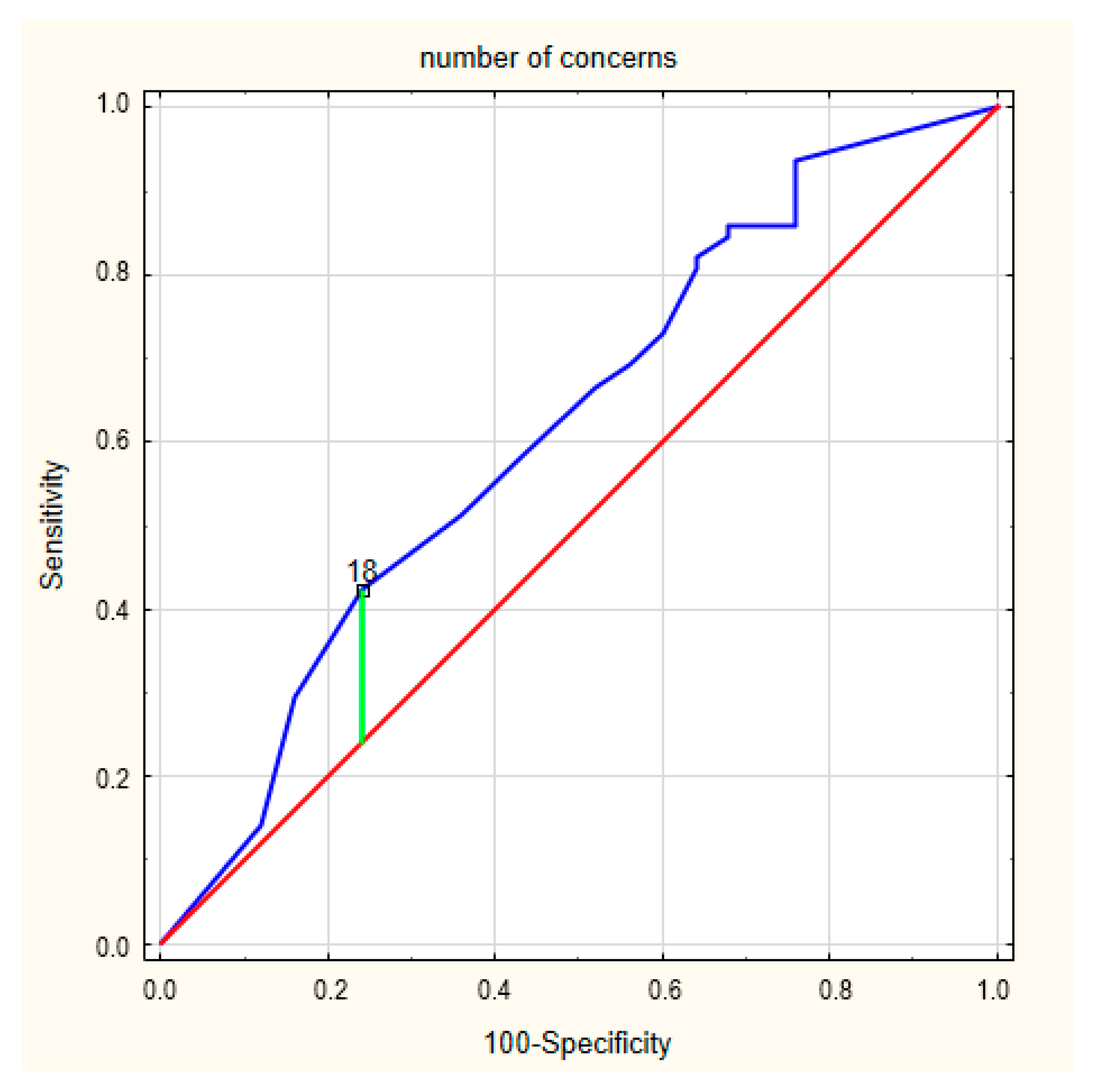

| Number of concerns | 14.55 ± 5.85 | 11.68 ± 7.49 | 13.85 ± 6.37 | 0.049406 |

| Severity of concerns | 21.59 ± 11.65 | 15.88 ± 13.23 | 20.20 ± 12.23 | 0.041722 |

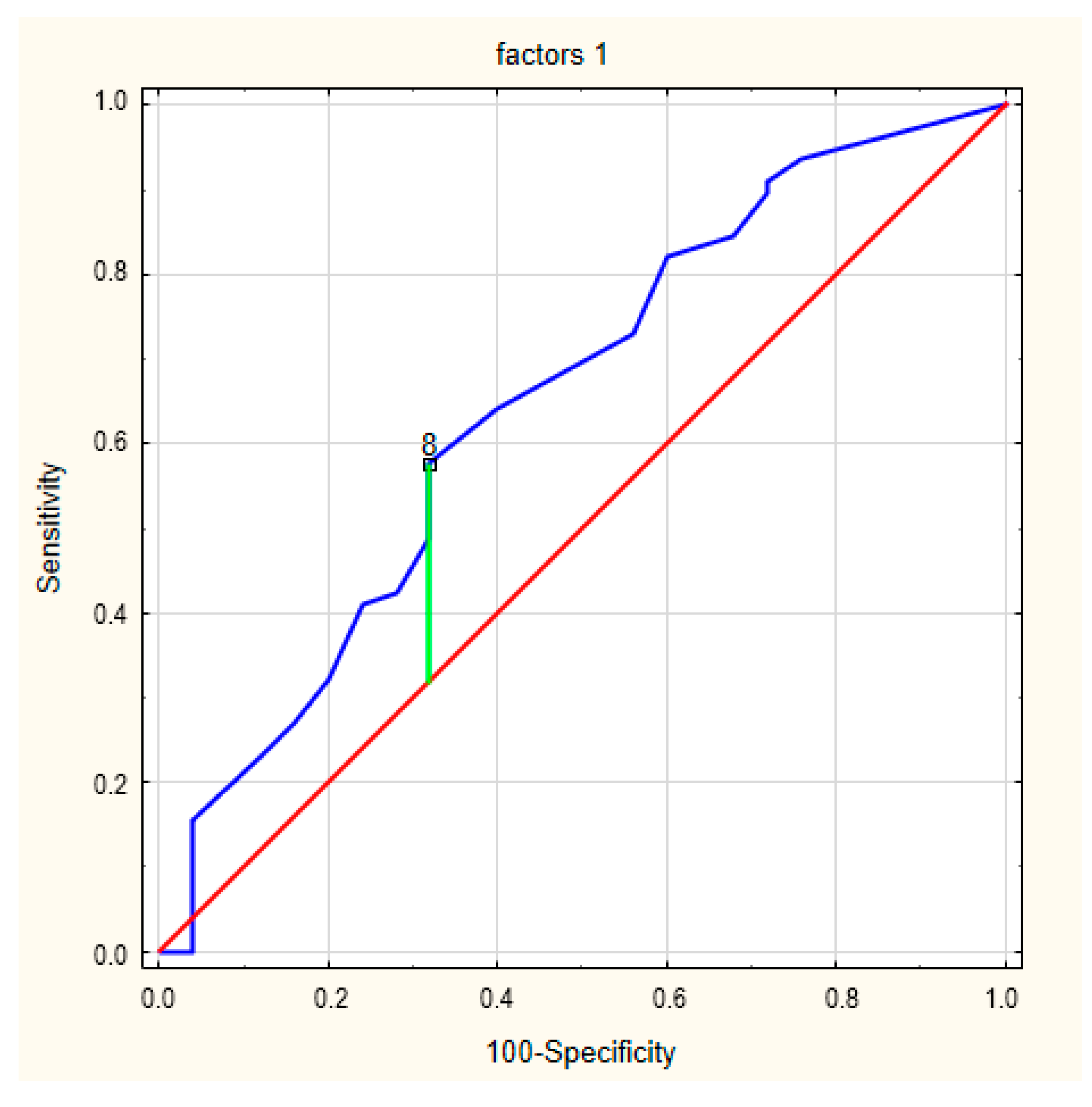

| Factor 1—perceived limitations | 8.93 ± 5.12 | 6.48 ± 5.92 | 8.34 ± 5.40 | 0.047413 |

| Factor 2—device-specific concerns | 9.63 ± 5.23 | 7.08 ± 5.52 | 9.01 ± 5.39 | 0.038913 |

| Parameter | Frailty Syndrome Global | Physical Domain | Psychological Domain | Social Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total questionnaire score | r = 0.5090 | r = 0.4804 | r = 0.3340 | r = 0.2274 |

| p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.021 | |

| Number of concerns | r = 0.4744 | r = 0.4236 | r = 0.3506 | r = 0.2125 |

| p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.031 | |

| Severity of concerns | r = 0.5079 | r = 0.4920 | r = 0.3128 | r = 0.2267 |

| p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.021 | |

| Factor 1—perceived limitations | r = 0.4972 | r = 0.4885 | r = 0.2801 | r = 0.2511 |

| p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.004 | p = 0.011 | |

| Factor 2—device-specific concerns | r = 0.4917 | r = 0.4647 | r = 0.3223 | r = 0.2186 |

| p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.027 |

| Rating | Standard Error | Wald x2 | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total questionnaire score | 0.026153 | 0.012898 | 4.1117 | 1.0265 | 1.0009–1.0528 | 0.0426 |

| Number of concerns | 0.065835 | 0.034166 | 3.7126 | 1.0680 | 0.9989–1.1420 | 0.0540 |

| Severity of concerns | 0.040839 | 0.020379 | 4.0161 | 1.0417 | 1.0009–1.0841 | 0.0451 |

| Factor 1—perceived limitations | 0.091981 | 0.047114 | 3.8115 | 1.0963 | 0.9996–1.2024 | 0.0509 |

| Factor 2—device-specific concerns | 0.093687 | 0.046153 | 4.1205 | 1.0982 | 1.0032–1.2022 | 0.0424 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mlynarska, A.; Mlynarski, R.; Uchmanowicz, I.; Marcisz, C.; Golba, K.S. The Relationship between Frailty Syndrome and Concerns about an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1954. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17061954

Mlynarska A, Mlynarski R, Uchmanowicz I, Marcisz C, Golba KS. The Relationship between Frailty Syndrome and Concerns about an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):1954. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17061954

Chicago/Turabian StyleMlynarska, Agnieszka, Rafal Mlynarski, Izabella Uchmanowicz, Czeslaw Marcisz, and Krzysztof S. Golba. 2020. "The Relationship between Frailty Syndrome and Concerns about an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 6: 1954. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17061954