Concurrent Daily and Non-Daily Use of Heated Tobacco Products with Combustible Cigarettes: Findings from the 2018 ITC Japan Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. User Definitions

2.2.2. Sociodemographic Measures

2.2.3. Pattern of Product Use

2.2.4. Beliefs toward HTPs and Cigarettes

2.2.5. Smoking Cessation-Related Behaviors

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Proportion and Characteristics of Exclusive and Concurrent User of Cigarette and HTP

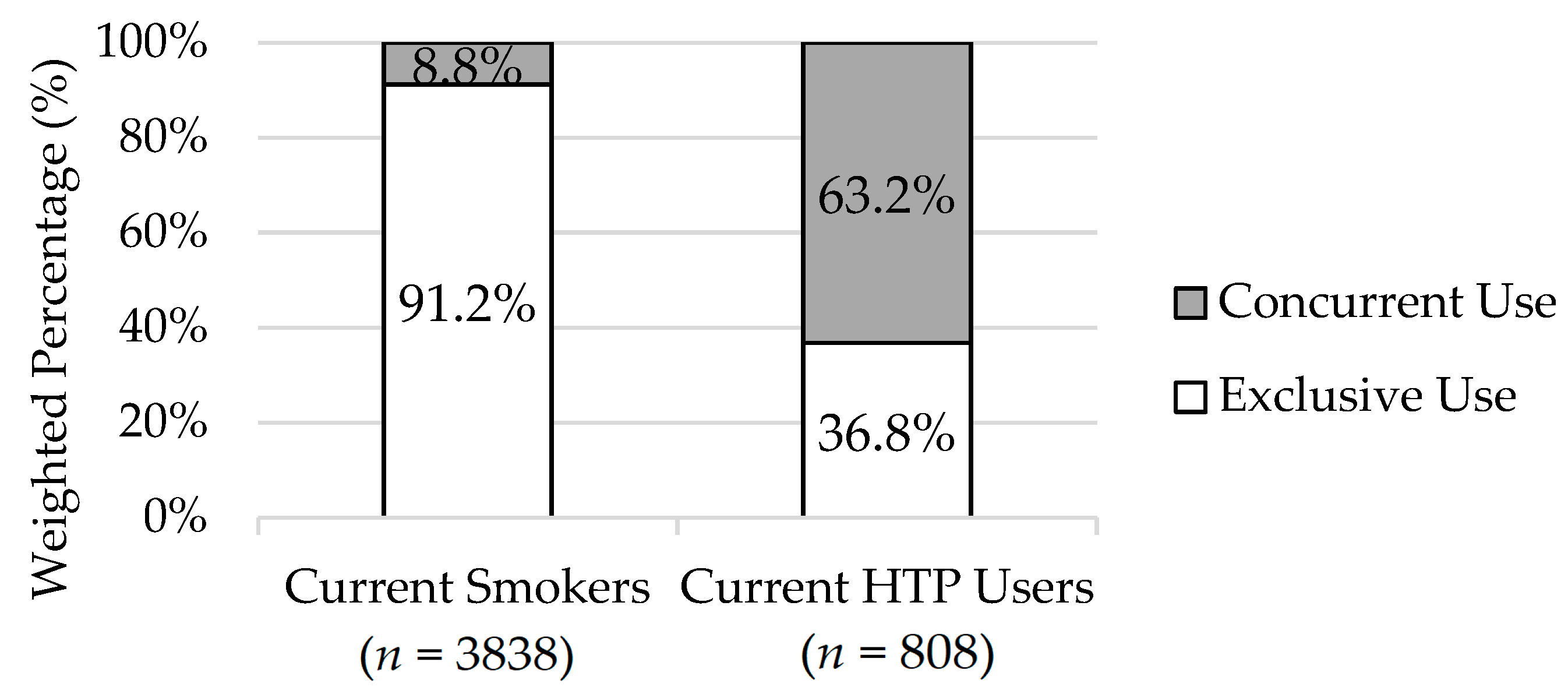

3.1.1. Proportion of Exclusive and Concurrent User of Cigarette and HTP

3.1.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Exclusive and Concurrent User of Cigarette and HTP

3.1.3. Pattern of Product Use of Exclusive and Concurrent User of Cigarette and HTP

3.1.4. Beliefs and Smoking Cessation-Related Behaviors of Exclusive and Concurrent User of Cigarette and HTP

3.2. Proportion and Characteristics of Subgroups of Concurrent Cigarette-HTP Users

3.2.1. Proportion of Subgroups of Concurrent Cigarette-HTP Users

3.2.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Subgroups of Concurrent Cigarette-HTP Users

3.2.3. Pattern of Product Use of Subgroups of Concurrent Cigarette-HTP Users

3.2.4. Beliefs and Smoking Cessation-Related Behaviors of Subgroups of Concurrent Cigarette-HTP Users

3.3. Differences among Daily Users

3.3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Daily Users

3.3.2. Pattern of Product Use of Daily Users

3.3.3. Beliefs and Smoking Cessation-Related Behaviors of Daily Users

3.4. Differences among Non-Daily Users

3.4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Subgroups of Non-Daily Users

3.4.2. Pattern of Product Use of Subgroups of Non-Daily Users

3.4.3. Beliefs and Smoking Cessation-Related Behaviors of Subgroups of Non-Daily Users

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Concurrent Cigarette-HTP Users

4.2. Characteristics of Subgroups of Concurrent Cigarette-HTP Users

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tabuchi, T.; Gallus, S.; Shinozaki, T.; Nakaya, T.; Kunugita, N.; Colwell, B. Heat-not-burn tobacco product use in Japan: Its prevalence, predictors and perceived symptoms from exposure to secondhand heat-not-burn tobacco aerosol. Tob. Control. 2017, 27, e25–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Euromonitor International. Smokeless Tobacco in Japan. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/smokeless-tobacco-in-japan/report (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- American Cancer Society, Vital Strategies. Japan Country Facts. The Tobacco Atlas. 2018. Available online: https://files.tobaccoatlas.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/japan-country-facts-en.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Uranaka, T.; Ando, R. Philip Morris Aims to Revive Japan Sales with Cheaper Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco. Reuters. Tokyo; 2018. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pmi-japan/philip-morris-aims-to-revive-japan-sales-with-cheaper-heat-not-burn-tobacco-idUSKCN1MX06E (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Tabuchi, T.; Kiyohara, K.; Hoshino, T.; Bekki, K.; Inaba, Y.; Kunugita, N. Awareness and use of electronic cigarettes and heat-not-burn tobacco products in Japan. Addiction 2016, 111, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Tobacco Inc. JT’s Annual Survey Finds 21.1 Percent of Japanese Adults Are Smokers. 2018. Available online: https://www.jt.com/investors/media/press_releases/2012/0730_01.html (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Sutanto, E.; Miller, C.R.; Smith, D.M.; O’Connor, R.J.; Quah, A.C.; Cummings, K.M.; Xu, S.; Fong, G.T.; Hyland, A.; Ouimet, J.; et al. Prevalence, Use Behaviors, and Preferences among Users of Heated Tobacco Products: Findings from the 2018 ITC Japan Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, J.H.; Ryu, D.H.; Park, S.-W. Heated tobacco products: Cigarette complements, not substitutes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 204, 107576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, A.; Nagaraja, H.N.; Cooper, S.; E Wewers, M. Tobacco product transition patterns in rural and urban cohorts: Where do dual users go? Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaura, R.; Rich, I.; Johnson, A.L.; Villanti, A.C.; Romberg, A.R.; Hair, E.C.; Vallone, D.M.; Abrams, D.B. Young Adult Tobacco and E-cigarette Use Transitions: Examining Stability using Multi-State Modeling. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.E.; Baker, T.B.; Benowitz, N.L.; E Jorenby, U. Changes in Use Patterns Over 1 Year Among Smokers and Dual Users of Combustible and Electronic Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.R.; Smith, D.M.; Goniewicz, M.L. Changes in Nicotine Product Use among Dual Users of Tobacco and Electronic Cigarettes: Findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013–2015. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR). Health Effects of Smokeless Tobacco Products. Brussel; 2008. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_risk/committees/04_scenihr/docs/scenihr_o_013.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes; Eaton, D.L., Kwan, L.Y., Stratton, K., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://0-www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.brum.beds.ac.uk/books/NBK507171/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK507171.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- McNeill, A.; Brose, L.; Calder, R.; Bauld, L.; Dobson, D. Evidence Review of E-Cigarettes and Heated Tobacco Products 2018; Public Health England: London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/684963/Evidence_review_of_e-cigarettes_and_heated_tobacco_products_2018.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Farsalinos, K.E.; Romagna, G.; Voudris, V. Factors associated with dual use of tobacco and electronic cigarettes: A case control study. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goniewicz, M.L.; Smith, D.M.; Edwards, K.C.; Blount, B.C.; Caldwell, K.L.; Feng, J.; Wang, L.; Christensen, C.; Ambrose, B.; Borek, N.; et al. Comparison of Nicotine and Toxicant Exposure in Users of Electronic Cigarettes and Combustible Cigarettes. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e185937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shahab, L.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Blount, B.C.; Brown, J.; McNeill, A.; Alwis, K.U.; Feng, J.; Wang, L.; West, R. Nicotine, carcinogen and toxicant exposure in long-term e-cigarette and nicotine replacement therapy users: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tverdal, A.; Bjartveit, K. Health consequences of reduced daily cigarette consumption. Tob. Control. 2006, 15, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hart, C.; Gruer, L.; Bauld, L. Does smoking reduction in midlife reduce mortality risk? Results of 2 long-term prospective cohort studies of men and women in Scotland. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 178, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, Y.; Myers, V.; Goldbourt, U. Smoking Reduction at Midlife and Lifetime Mortality Risk in Men: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 175, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leigh, N.J.; Palumbo, M.N.; Marino, A.M.; O’Connor, R.J.; Goniewicz, M.L. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNA) in heated tobacco product IQOS. Tob. Control. 2018, 27, s37–s38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farsalinos, K.E.; Yannovits, N.; Sarri, T.; Voudris, V.; Poulas, K.; Leischow, S.J. Carbonyl emissions from a novel heated tobacco product (IQOS): Comparison with an e-cigarette and a tobacco cigarette. Addiction 2018, 113, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, R.; Murray, K.; Gravely, S.; Fong, G.T.; Thompson, M.E.; McNeill, A.; O’Connor, R.J.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Yong, H.-H.; Levy, D.T.; et al. A new classification system for describing concurrent use of nicotine vaping products alongside cigarettes (so-called ‘dual use’): Findings from the ITC-4 Country Smoking and Vaping wave 1 Survey. Addiction 2019, 114, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Kozlowski, L.T.; Frecker, R.C.; Fagerstrom, K.-O. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Addiction 1991, 86, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sung, H.-Y.; Yao, T.; Lightwood, J.; Max, W. Infrequent and Frequent Nondaily Smokers and Daily Smokers: Their Characteristics and Other Tobacco Use Patterns. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017, 20, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roulet, S.; Chrea, C.; Kanitscheider, C.; Kallischnigg, G.; Magnani, P.; Weitkunat, R. Potential predictors of adoption of the Tobacco Heating System by U.S. adult smokers: An actual use study. F1000Research 2019, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soneji, S.; Sargent, J.D.; Tanski, S.E.; Primack, B.A. Associations between initial water pipe tobacco smoking and snus use and subsequent cigarette smoking: Results from a longitudinal study of US adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Whitsel, L.P.; Blaha, M.J.; Huffman, M.D.; Krishan-Sarin, S.; Maa, J.; Rigotti, N.; Robertson, R.M.; Warner, J.J.; on behalf of the American Heart Association. New and Emerging Tobacco Products and the Nicotine Endgame: The Role of Robust Regulation and Comprehensive Tobacco Control and Prevention: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, 937–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, D.; Arrazola, R.A.; Tworek, C.; Rolle, I.V.; Neff, L.J.; Portnoy, D. Openness to Using Non-cigarette Tobacco Products Among U.S. Young Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 50, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKelvey, K.; Popova, L.; Kim, M.; Chaffee, B.W.; Vijayaraghavan, M.; Ling, P.; Halpern-Felsher, B. Heated tobacco products likely appeal to adolescents and young adults. Tob. Control. 2018, 27, s41–s47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, E.C.; Bennett, M.; Sheen, E.; Cantrell, J.; Briggs, J.; Fenn, Z.; Willett, J.G.; Vallone, D. Examining perceptions about IQOS heated tobacco product: Consumer studies in Japan and Switzerland. Tob. Control. 2018, 27, s70–s73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, N.J.; Tran, P.L.; O’Connor, R.J.; Goniewicz, M.L. Cytotoxic effects of heated tobacco products (HTP) on human bronchial epithelial cells. Tob. Control. 2018, 27, s26–s29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sohal, S.S.; Eapen, M.S.; Naidu, V.G.; Sharma, P. IQOS exposure impairs human airway cell homeostasis: Direct comparison with traditional cigarette and e-cigarette. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00159-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomar, S.L.; Alpert, H.R.; Connolly, G.N. Patterns of dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco among US males: Findings from national surveys. Tob. Control. 2009, 19, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lund, K.E.; McNeill, A. Patterns of dual use of snus and cigarettes in a mature snus market. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012, 15, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanigaki, J.; Poudyal, H. Challenges and opportunities for greater tobacco control in Japan. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 70, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tada, A.; Kiya, M.; Okamoto, R. The status and future directions of comprehensive tobacco control policies for the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games: A review. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2019, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, A.; Schwartz, R.; O’Connor, S.; Fung, M.; Diemert, L. Marketing IQOS in a dark market. Tob. Control. 2018, 28, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Philip Morris International introduces new heat-not-burn product, IQOS, in South Korea. Tob. Control. 2017, 27, e76–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, C.; Burnley, A.; McNeill, A.; Hitchman, S.C. Factors that influence smokers’ and ex-smokers’ use of IQOS: A qualitative study of IQOS users and ex-users in the UK. Tob. Control. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, C.J.; Stratton, E.; Schauer, G.L.; Lewis, M.; Wang, Y.; Windle, M.; Kegler, M. Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: Marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Subst. Use Misuse 2014, 50, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.V.; Morrell, H.E.R.; Cornell, J.L.; Ramos, M.E.; Biehl, M.; Kropp, R.Y.; Halpern-Felsher, B.L. Perceptions of Smoking-Related Risks and Benefits as Predictors of Adolescent Smoking Initiation. Am. J. Public Heal. 2009, 99, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrock, S.; Zakhar, J.; Zhou, S.; Weitzman, M. Perception of E-Cigarette Harm and Its Correlation With Use Among U.S. Adolescents. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014, 17, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, N.; Cleland, C.; Wang, M.P.; Kwong, A.; Lai, V.W.Y.; Lam, T.H. Perceptions and use of e-cigarettes among young adults in Hong Kong. BMC Public Heal. 2019, 19, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baig, S.A.; Giovenco, D.P. Behavioral heterogeneity among cigarette and e-cigarette dual-users and associations with future tobacco use: Findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Addict. Behav. 2020, 104, 106263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Outline of the Act on the Partial Revision of the Health Promotion Act (No. 78 of 2018); Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/health-medical/health/dl/201904kenko.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Assunta, M.; Chapman, S. A “clean cigarette” for a clean nation: A case study of Salem Pianissimo in Japan. Tob. Control. 2004, 13, ii58–ii62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) Exclusive Smokers (n = 3194) | (B) Concurrent Cigarette-HTP Users (n = 644) | (C) Exclusive HTP Users (n = 164) | Significance * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % [95% Confidence Interval] | |||||

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Gender | Male | 69.2 [67.3–71.1] | 78.8 [73.8–83.0] | 71.8 [63.7–78.6] | A–B: 0.0007 |

| Female | 30.8 [28.9–32.7] | 21.2 [17.0–26.2] | 28.2 [21.4–36.3] | B–C: NS | |

| Age (years old) | 20–29 | 9.4 [8.3–10.6] | 19.7 [15.6–24.5] | 12.3 [6.8–21.1] | A–B < 0.0001 |

| 30–39 | 19.2 [17.7–20.7] | 28.3 [24.2–32.8] | 23.2 [16.9–31.1] | B–C: 0.0022 | |

| 40–59 | 41.2 [39.4–43.1] | 36.4 [31.9–41.1] | 57.0 [47.9–65.7] | ||

| 60 and older | 30.2 [28.5–32.0] | 15.7 [12.2–19.9] | 7.4 [3.8–14.2] | ||

| Annual Household Income | Low | 28.9 [27.2–30.7] | 16.4 [13.2–20.2] | 14.1 [9.2–21.0] | A–B < 0.0001 |

| Moderate | 21.9 [20.4–23.5] | 24.0 [20.0–28.4] | 20.0 [13.9–27.9] | B–C: NS | |

| High | 35.4 [33.7–37.3] | 47.9 [43.0–52.8] | 60.0 [51.1–68.2] | ||

| Refused/Do not know | 13.7 [12.5–15.1] | 11.8 [8.1–16.7] | 5.9 [3.0–11.1] | ||

| Education | Low | 32.3 [30.6–34.1] | 25.7 [22.0–29.8] | 24.5 [18.3–32.1] | A–B: 0.0052 |

| Moderate | 22.0 [20.3–23.8] | 21.1 [16.6–26.4] | 24.2 [18.0–31.7] | B–C: NS | |

| High | 44.4 [42.5–46.3] | 52.8 [47.8–57.8] | 50.9 [42.0–59.7] | ||

| Refused/Do not know | 1.2 [0.9–1.8] | 0.4 [0.1–1.1] | 0.4 [0.1–2.8] | ||

| Pattern of Product Use | |||||

| Frequency of Smoking | Daily | 94.8 [93.9–95.5] | 93.9 [91.2–95.9] | NA | A–B: NS |

| Non-daily | 5.2 [4.5–6.1] | 6.1 [4.1–8.8] | NA | ||

| Frequency of HTP Use | Daily | NA | 48.8 [43.9–53.8] | 89.1 [81.8–93.7] | B–C < 0.0001 |

| Non-daily | NA | 51.1 [46.2–56.0] | 10.9 [6.3–18.2] | ||

| Cigarettes per day † | 15.0 [10.0–20.0] | 15.0 [10.0–20.0] | NA | A–B: NS | |

| Tobacco-containing inserts per day † | NA | 5.0 [1.4–12.0] | 10.0 [5.0–20.0] | B–C < 0.0001 | |

| Time to first tobacco product use | 5 min or less | 26.4 [24.7–28.1] | 26.9 [23.0–31.2] | 19.3 [13.4–27.1] | A–B: 0.0384 |

| 6–30 min | 39.5 [37.7–41.4] | 44.2 [39.2–49.3] | 39.0 [30.7–48.1] | B–C: 0.0336 | |

| 31–60 min | 15.7 [14.3–17.1] | 16.6 [13.4–20.5] | 19.8 [13.4–28.4] | ||

| More than 60 min | 18.4 [17.0–19.9] | 12.3 [9.5–15.7] | 21.8 [15.1–30.4] | ||

| Beliefs toward HTPs and cigarettes | |||||

| Believes HTPs are much or somewhat less addictive than cigarettes ‡ | 20.0 [18.5–21.7] | 42.7 [37.9–47.6] | 47.9 [39.1–56.9] | A–B < 0.0001 | |

| B–C: NS | |||||

| Believes HTPs are much or somewhat less harmful to users than cigarettes ‡ | 43.7 [41.8–45.7] | 69.7 [64.9–74.0] | 88.2 [81.2–92.8] | A–B < 0.0001 | |

| B–C: 0.0001 | |||||

| Believes secondhand emissions from HTPs are much or somewhat less harmful than secondhand emissions from cigarettes ‡ | 50.3 [48.3–52.2] | 71.9 [67.1–76.2] | 86.3 [79.5–91.1] | A–B < 0.0001 | |

| B–C < 0.0001 | |||||

| Agrees society strongly or somewhat disapproves using HTPs ‡ | 23.5 [21.8–25.2] | 23.0 [18.5–28.3] | 29.5 [22.1–38.2] | A–B < 0.0001 | |

| B–C: NS | |||||

| Agrees society strongly or somewhat disapproves using cigarettes ‡ | 64.9 [63.0–66.7] | 64.0 [59.4–68.5] | 59.8 [50.8–68.2] | A–B: NS | |

| B–C: NS | |||||

| Has very positive or positive overall opinions of HTPs ‡ | 28.0 [26.2–29.8] | 56.2 [51.2–61.1] | 62.5 [53.3–70.9] | A–B < 0.0001 | |

| B–C: NS | |||||

| Has very positive or positive overall opinions of cigarettes ‡ | 37.5 [35.6–39.3] | 45.9 [41.0–50.9] | 34.4 [26.6–43.2] | A–B: 0.0075 | |

| B–C: 0.0119 | |||||

| Smoking Cessation-related Behaviors | |||||

| Attempted to quit at least once in the last 12 months | 50.4 [47.9–52.9] | 54.2 [47.4–60.9] | NA | A–B: NS | |

| Plans to quit smoking cigarettes in the next 6 months | 9.0 [7.9–10.3] | 11. 8 [9.2–15.1] | NA | A–B: NS | |

| Weighted % [95% Confidence Interval] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Daily HTP User (n = 550) | Non-daily HTP User (n = 258) | |

| 48.8 [43.9–53.8]* | 51.1 [46.2–56.0] * | |

| Daily smoker (n = 3626) | Dual Daily User (n = 396) | Predominant Smoker (n = 213) |

| 93.9 [91.2–95.9] † | 48.4 [43.5–53.3] | 45.5 [40.5–50.7] |

| Non-daily smoker (n = 212) | Predominant HTP User (n = 4) | Concurrent Non-daily User (n = 31) |

| 6.1 [4.1–8.8] † | 0.5 [0.2–1.3] | 5.6 [3.7–8.3] |

| (A) Concurrent Daily User (n = 609) * | (B) Concurrent Non-Daily User (n = 31) | Significance † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % [95% Confidence Interval] | ||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Gender | Male | 79.2 [74.0–83.7] | 70.5 [47.6–86.3] | A-B: NS |

| Female | 20.7 [16.3–26.0] | 29.5 [13.7–52.4] | ||

| Age (years old) | 20–29 | 18.1 [14.0–23.2] | 40.3 [22.6–61.0] | A-B: 0.0146 |

| 30–39 | 27.9 [23.6–32.6] | 36.1 [19.2–57.4] | ||

| 40–59 | 37.5 [32.9–42.4] | 20.3 [7.4–44.8] | ||

| 60 and older | 16.5 [12.7–21.0] | 3.2 [0.8–12.6] | ||

| Annual Household Income | Low | 15.8 [12.6–19.6] | 22.4 [8.5–47.2] | A-B: NS |

| Moderate | 24.4 [20.2–29.1] | 19.1 [8.5–37.5] | ||

| High | 47.7 [42.6–52.8] | 51.5 [31.6–71.0] | ||

| Refused/Do not know | 12.1 [8.3–17.4] | 7.0 [1.9–22.3] | ||

| Education | Low | 26.5 [22.6–30.7] | 11.3 [4.4–26.3] | A-B: NS |

| Moderate | 21.2 [16.6–26.8] | 19.0 [6.6–43.9] | ||

| High | 52.1 [46.8–57.2] | 67.5 [45.8–83.6] | ||

| Refused/Do not know | 0.2 [0.1–0.9] | 2.2 [0.3–14.4] | ||

| Pattern of Product Use | ||||

| Cigarettes per day ‡ | 15.0 [10.0–20.0] | 2.9 [1.3–6.0] | A-B < 0.0001 | |

| Tobacco-containing inserts per day ‡ | 6.0 [1.4–15.0] | 1.4 [0.4–2.8] | A-B < 0.0001 | |

| Time to first tobacco product use | 5 min or less | 27.9 [23.8–32.5] | 10.4 [3.1–29.7] | A-B < 0.0001 |

| 6–30 min | 45.6 [40.5–50.9] | 18.2 [6.5–41.3] | ||

| 31–60 min | 16.0 [12.7–19.9] | 27.3 [12.3–50.2] | ||

| More than 60 min | 10.4 [7.8–13.8] | 44.1 [25.6–64.4] | ||

| Beliefs toward HTPs and cigarettes | ||||

| Believes HTPs are much or somewhat less addictive than cigarettes § | 41.7 [36.8–46.8] | 59.8 [38.7–77.9] | A-B: NS | |

| Believes HTPs are much or somewhat less harmful to users than cigarettes§ | 68.9 [64.0–73.5] | 84.1 [64.6–93.8] | A-B: NS | |

| Believes secondhand emissions from HTP much or somewhat less harmful than secondhand emissions from cigarettes § | 72.3 [67.3–76.7] | 65.8 [43.0–83.1] | A-B: NS | |

| Agrees society strongly or somewhat disapproves using HTPs § | 23.6 [18.9–29.2] | 13.2 [4.3–34.2] | A-B: NS | |

| Agrees society strongly or somewhat disapproves smoking cigarettes § | 65.3 [60.5–69.8] | 46.5 [27.4–66.6] | A-B: NS | |

| Has very positive or positive overall opinions of HTPs § | 55.9 [50.6–61.0] | 58.5 [37.1–77.1] | A-B: NS | |

| Has very positive or positive overall opinions of cigarettes § | 46.3 [41.2–51.5] | 39.2 [21.7–60.0] | A-B: NS | |

| Smoking Cessation-related Behaviors | ||||

| Attempted to quit at least once in the last 12 months | 51.9 [44.7–58.9] | 89.4 [67.0–97.2] | A-B: 0.0013 | |

| Plans to quit smoking cigarettes in the next 6 months | 9.3 [7.0–12.3] | 50.6 [30.2–70.9] | A-B < 0.0001 | |

| (A) Exclusive Daily Smoker (n = 3017) | Concurrent Daily Use * | (D) Exclusive Daily HTP User (n = 150) | Significance † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (B) Predominant Smoker (n = 213) | (C) Dual Daily User (n = 396) | |||||

| Weighted % | ||||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 68.7 | 80.1 | 78.5 | 71.6 | A-B: 0.0369 |

| Female | 31.3 | 19.9 | 21.5 | 28.4 | B-C: NS | |

| C-D: NS | ||||||

| Age | 20–29 | 8.5 | 12.2 | 23.7 | 11.1 | A-B: NS |

| 30–39 | 18.7 | 26.6 | 29.1 | 22.9 | B-C: 0.0036 | |

| 40–59 | 41.7 | 37.3 | 37.7 | 58.0 | C-D: 0.0070 | |

| 60 and older | 31.0 | 24.0 | 9.4 | 7.9 | ||

| Annual Household Income | Low | 28.6 | 14.9 | 16.7 | 15.8 | A-B: 0.0202 |

| Moderate | 22.2 | 24.4 | 24.3 | 18.8 | B-C: NS | |

| High | 35.4 | 46.3 | 49.0 | 59.7 | C-D: NS | |

| Refused/Do not know | 13.9 | 14.4 | 10.0 | 5.6 | ||

| Education | Low | 32.8 | 23.5 | 29.2 | 23.1 | A-B: NS |

| Moderate | 22.1 | 22.4 | 20.1 | 26.2 | B-C: NS | |

| High | 43.9 | 54.1 | 50.2 | 50.2 | C-D: NS | |

| Refused/Do not know | 1.2 | - | 0.5 | 0.5 | ||

| Pattern of Product Use | ||||||

| Cigarettes per day‡ | 15.0 (10.0–20.0) | 18.0 (10.0–20.0) | 15.0 (10.0–20.0) | NA | A-B: 0.0309 | |

| A-C: NS | ||||||

| Tobacco-containing inserts per day‡ | NA | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 10.0 (5.0–15.0) | 10.0 (7.0–20.0) | B-D<0.0001 | |

| C-D: 0.0076 | ||||||

| Time to first tobacco product use | 5 min or less | 27.5 | 27.2 | 28.6 | 20.1 | A-B: NS |

| 6–30 min | 40.9 | 46.2 | 45.1 | 40.7 | B-C: NS | |

| 31–60 min | 16.0 | 15.0 | 16.9 | 20.3 | C-D: NS | |

| More than 60 min | 15.6 | 11.6 | 9.4 | 18.8 | ||

| Beliefs toward HTPs and cigarettes | ||||||

| Believes HTPs are much or somewhat less addictive than cigarettes§ | 20.0 | 38.9 | 44.3 | 47.7 | A-B < 0.0001 | |

| B-C: NS | ||||||

| C-D: NS | ||||||

| Believes HTPs are much or somewhat less harmful to users than cigarettes§ | 44.2 | 64.8 | 72.8 | 90.0 | A-B<0.0001 | |

| B-C: NS | ||||||

| C-D: 0.0001 | ||||||

| Believes secondhand emissions from HTP much or somewhat less harmful than secondhand emissions from cigarettes§ | 50.7 | 70.3 | 74.2 | 87.3 | A-B<0.0001 | |

| B-C: NS | ||||||

| C-D<0.0001 | ||||||

| Agrees society strongly or somewhat disapproves using HTPs§ | 23.4 | 27.5 | 20.0 | 28.8 | A-B: NS | |

| B-C: 0.0307 | ||||||

| C-D: NS | ||||||

| Agrees society strongly or somewhat disapproves smoking cigarettes§ | 64.9 | 70.9 | 60.0 | 62.6 | A-B: NS | |

| B-D: NS | ||||||

| C-D: NS | ||||||

| Has very positive or positive overall opinions of HTPs§ | 28.2 | 47.9 | 63.4 | 64.7 | A-B < 0.0001 | |

| B-C: 0.0160 | ||||||

| C-D: NS | ||||||

| Has very positive or positive overall opinions of cigarettes§ | 37.9 | 49.1 | 43.7 | 37.7 | A-B: 0.0257 | |

| B-C: NS | ||||||

| C-D: NS | ||||||

| Smoking Cessation-related Behaviors | ||||||

| Attempted to quit at least once in the last 12 months | 49.3 | 48.8 | 54.3 | NA | A-B: NS | |

| A-C: NS | ||||||

| Plans to quit smoking cigarettes in the next 6 months | 8.0 | 4.9 | 14.0 | NA | A-B: NS | |

| A-C: 0.0017 | ||||||

| (A) Exclusive Non-Daily Smoker (n = 177) | (B) Concurrent Non-Daily User (n = 31) | (C) Exclusive Non-Daily HTP User (n = 14) | Significance * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % | |||||

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Gender | Male | 78.8 | 70.5 | 72.6 | A-B: NS |

| Female | 21.2 | 29.5 | 27.4 | B-C: NS | |

| Age | 20–29 | 24.9 | 40.3 | 21.6 | A-B: NS |

| 30–39 | 26.8 | 36.1 | 25.6 | B-C: NS | |

| 40–59 | 32.3 | 20.3 | 49.0 | ||

| 60 and older | 16.0 | 3.2 | 3.7 | ||

| Annual Household Income | Low | 34.8 | 22.4 | - | A-B: NS |

| Moderate | 17.4 | 19.1 | 29.6 | B-C: NS | |

| High | 36.8 | 51.5 | 62.5 | ||

| Refused/Do not know | 11.0 | 7.0 | 7.9 | ||

| Education | Low | 23.5 | 11.3 | 35.9 | A-B: NS |

| Moderate | 21.1 | 19.0 | 7.9 | B-C: NS | |

| High | 54.1 | 67.5 | 56.2 | ||

| Refused/Do not know | 1.3 | 2.2 | - | ||

| Pattern of Product Use | |||||

| Cigarettes per day † | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 2.9 (1.3–6.0) | NA | A-B: 0.0017 | |

| Tobacco-containing inserts per day† | NA | 1.4 (0.4–2.8) | 1.7 (0.7–7.1) | B-C: NS | |

| Time to first tobacco product use | 5 min or less | 3.2 | 10.4 | 11.6 | A-B: 0.0200 |

| 6–30 min | 13.6 | 18.2 | 22.6 | B-C: NS | |

| 31–60 min | 9.5 | 27.3 | 14.7 | ||

| More than 60 min | 73.7 | 44.1 | 51.1 | ||

| Beliefs toward HTPs and cigarettes | |||||

| Believes HTPs are much or somewhat less addictive than cigarettes ‡ | 20.1 | 59.8 | 49.9 | A-B: 0.0002 | |

| B-C: NS | |||||

| Believes HTPs are much or somewhat less harmful than cigarettes ‡ | 35.9 | 84.1 | 73.5 | A-B: 0.0008 | |

| B-C: NS | |||||

| Believes secondhand emissions from HTP much or somewhat less harmful than secondhand emissions from cigarettes ‡ | 43.4 | 65.8 | 78.1 | A-B: NS | |

| B-C: NS | |||||

| Agrees society strongly or somewhat disapproves using HTPs ‡ | 23.8 | 13.2 | 35.3 | A-B: 0.0422 | |

| B-C: NS | |||||

| Agrees society strongly or somewhat disapproves smoking cigarettes ‡ | 63.9 | 46.5 | 36.4 | A-B: NS | |

| B-C: 0.0317 | |||||

| Has very positive or positive overall opinions of HTPs ‡ | 24.5 | 58.5 | 44.2 | A-B: 0.0202 | |

| B-C: NS | |||||

| Has very positive or positive overall opinions of cigarettes ‡ | 28.6 | 39.2 | 7.5 | A-B: NS | |

| B-C: NS | |||||

| Smoking Cessation-related Behaviors | |||||

| Attempted to quit at least once in the last 12 months | 68.3 | 89.4 | NA | A-B: NS | |

| Plans to quit smoking cigarettes in the next 6 months | 25.9 | 50.6 | NA | A-B: 0.0215 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sutanto, E.; Miller, C.; Smith, D.M.; Borland, R.; Hyland, A.; Cummings, K.M.; Quah, A.C.K.; Xu, S.S.; Fong, G.T.; Ouimet, J.; et al. Concurrent Daily and Non-Daily Use of Heated Tobacco Products with Combustible Cigarettes: Findings from the 2018 ITC Japan Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2098. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17062098

Sutanto E, Miller C, Smith DM, Borland R, Hyland A, Cummings KM, Quah ACK, Xu SS, Fong GT, Ouimet J, et al. Concurrent Daily and Non-Daily Use of Heated Tobacco Products with Combustible Cigarettes: Findings from the 2018 ITC Japan Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):2098. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17062098

Chicago/Turabian StyleSutanto, Edward, Connor Miller, Danielle M. Smith, Ron Borland, Andrew Hyland, K. Michael Cummings, Anne C.K. Quah, Steve Shaowei Xu, Geoffrey T. Fong, Janine Ouimet, and et al. 2020. "Concurrent Daily and Non-Daily Use of Heated Tobacco Products with Combustible Cigarettes: Findings from the 2018 ITC Japan Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 6: 2098. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17062098