Employee-Organization Fit and Voluntary Green Behavior: A Cross-Level Model Examining the Role of Perceived Insider Status and Green Organizational Climate

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Person-Environment Fit Theory and Voluntary Green Behavior

2.2. The Mediating Role of Perceived Insider Status

2.3. The Moderating Role of Green Organizational Climate

3. Methodology

3.1. Samples and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Employee-Organization Fit

3.2.2. Perceived Insider Status

3.2.3. Green Organizational Climate

3.2.4. Voluntary Green Behavior

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

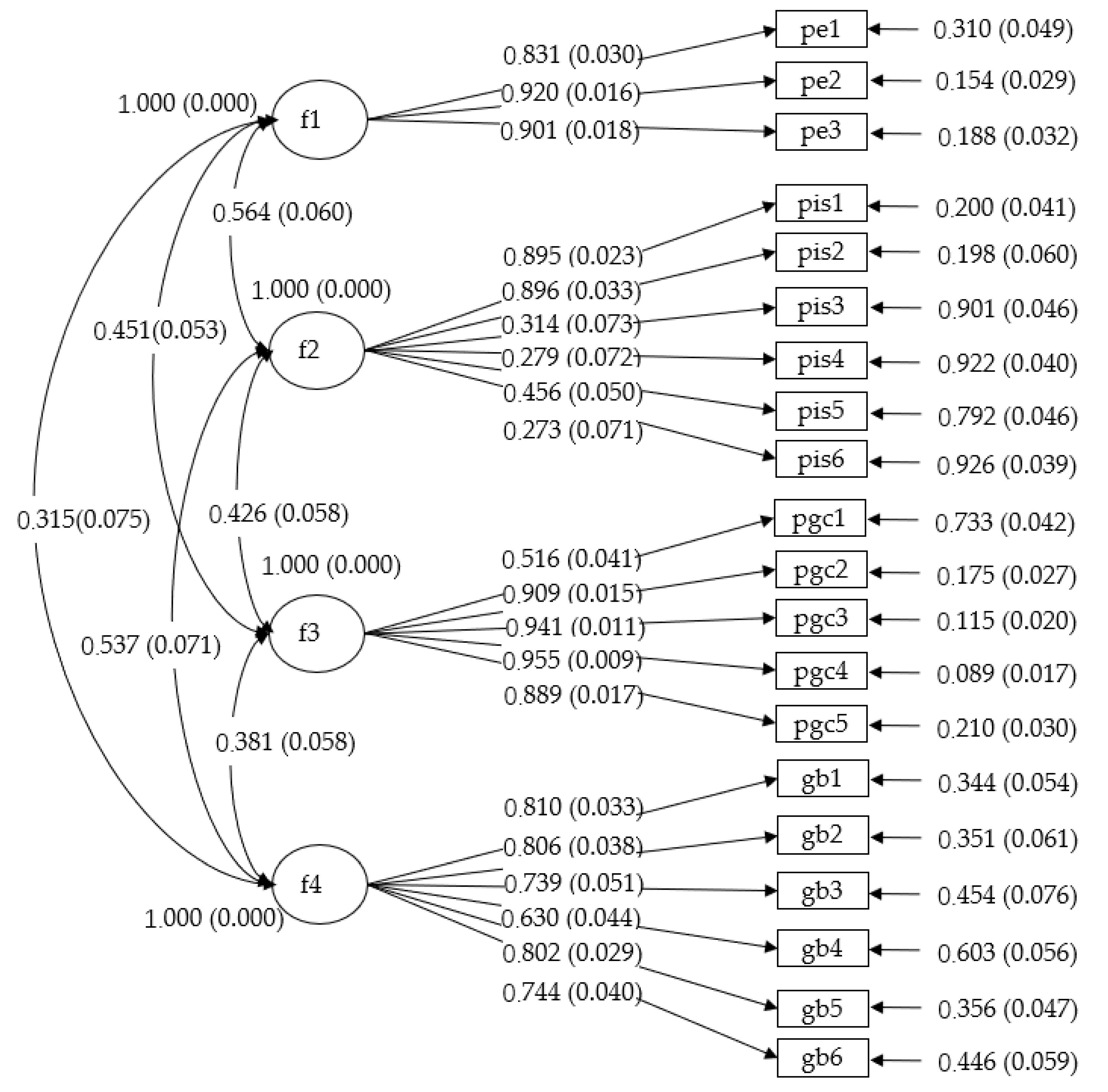

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

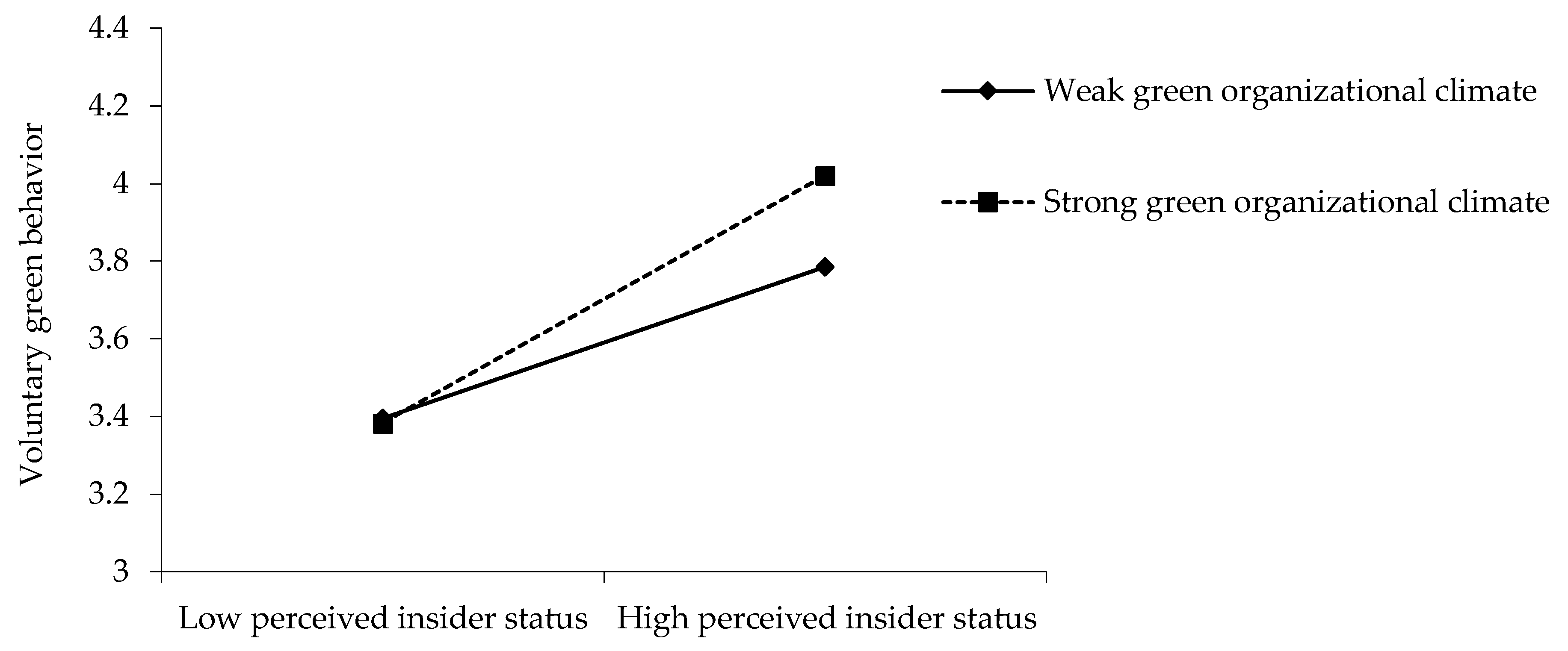

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Items |

|---|---|

| Employee-Organization Fit | 1. The things that I value in life are very similar to the things that my organization values. |

| 2. My personal values match my organization’s values and culture. | |

| 3. My organization’s values and culture provide a good fit with the things that I value in life. | |

| Perceived Insider Status | 1. I feel very much a part of my work organization. |

| 2. My work organization makes me believe that I am included in it. | |

| 3. I feel like I am an ‘outsider’ at this organization (R). | |

| 4. I don’t feel included in this organization (R). | |

| 5. I feel I am an ‘insider’ in my work organization. | |

| 6. My work organization makes me frequently feel ‘left-out’ (R). | |

| Green Organizational Climate | The extent to which your company is: |

| 1. Worried about its environmental impact. | |

| 2. Interested in supporting environmental causes. | |

| 3. Believes it is important to protect the environment. | |

| 4. Concerned with becoming more environmentally friendly. | |

| 5. Would like to be seen as environmentally friendly. | |

| Voluntary Green Behavior | Thinking about your work, to what extent do you…? |

| 1. Avoid unnecessary printing to save papers. | |

| 2. Use personal cups instead of disposable cups. | |

| 3. Use stairs instead of elevators when going from floor to floor in the building. | |

| 4. Reuse papers to take notes in the office. | |

| 5. Recycle reusable things in the workplace. | |

| 6. Sort recyclable materials into their appropriate bins when other group members do not recycle them. | |

| Environmental Attitude | 1. It is still the case that the major part of the population does not act in an environmentally conscious way. |

| 2. There are limits to economic growth which our industrialized world has crossed or will reach very soon. | |

| 3. Environmental-protection measures should be carried out even if this reduces the number of jobs in the economy. | |

| 4. Thinking about the environmental conditions our children and grandchildren have to live under, worries me. | |

| 5. When I read newspaper articles about environmental problems or view such TV-reports, I am indignant and angry. | |

| 6. If we continue as before, we are approaching an environmental catastrophe. | |

| 7. It is still true that politicians do far too little for environmental protection. | |

| 8. For the benefit of the environment we should be prepared to restrict our momentary style of living |

References

- Andersson, L.; Jackson, S.E.; Russell, S.V. Greening organizational behavior: An introduction to the special issue. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holme, R.; Watts, P. Corporate Social Responsibility: Making Good Business Sense; World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental sustainability at work: A call to action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and employee green behavior: The role of green psychological climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Talbot, D.; Paillé, P. Leading by example: A model of organizational citizenship behavior for the environment. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2015, 24, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Employee green behaviors. In Managing HR for Environmental Sustainability; Jackson, S.E., Ones, D.S., Dilchert, S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 85–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, K.L.; Dmitrieva, A.; Adriasola, E. Changing behavior: Increasing the effectiveness of workplace interventions in creating pro-environmental behavior change. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organizational sustainability policies and employee green behavior: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee green behavior: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. How green human resource management can promote green employee behavior in China: A technology acceptance model perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P.; Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O. The measurement of green workplace behaviors: A systematic review. Organ. Environ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.; Han, H.S.; Holland, S. The determinants of hospitality employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: The moderating role of generational differences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. How transformational leadership and employee motivation combine to predict employee pro-environmental behaviors in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1996; Volume 18, pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Afsar, B.; Badir, Y.; Kiani, U.S. Linking spiritual leadership and employee pro-environmental behavior: The influence of workplace spirituality, intrinsic motivation, and environmental passion. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decision Processes. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Dumont, J.; Deng, X. Employees’ perceptions of green HRM and non-green employee work outcomes: The social identity and stakeholder perspectives. Group Organ. Manag. 2018, 43, 594–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, F.V. Developing an integrated conceptual framework of pro-environmental behavior in the workplace through synthesis of the current literature. Admin. Sci. 2014, 4, 276–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Alfaro-Barrantes, P. Pro-environmental behavior in the workplace: A review of empirical studies and directions for future research. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2015, 120, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, A.E. Person-environment fit: A review of its basic tenets. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, J.; Dehghanpour Farashah, A.; Kazemi, M. The impact of person-job fit and person-organization fit on OCB: The mediating and moderating effects of organizational commitment and psychological empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 672–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Li, C.S.; Schneider, B. Fitting in and doing good: A review of person-environment fit and organizational citizenship behavior research. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior; Podsakoff, P.M., Scott, B., Mackenzie Podsakoff, N.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vleugels, W.; De Cooman, R.; Verbruggen, M.; Solinger, O. Understanding dynamic change in perceptions of person–environment fit: An exploration of competing theoretical perspectives. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Woehr, D.J. A quantitative review of the relationship between person-organization fit and behavioral outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.S.; Chiang, H.H.; McConville, D.; Chiang, C.L. A longitudinal investigation of person-organization fit, person-job fit, and contextual performance: The mediating role of psychological ownership. Hum. Perform. 2015, 28, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Cable, D.M. The value of value congruence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, K.Y.T. A motivational model of person-environment fit: Psychological motives as drivers of change. In Organizational Fit: Key Issues and New Directions; Kristof-Brown, A.L., Billsberry, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, I.R.; Shipp, A.I. The relationship between person-environment fit and outcomes: An integrative. In Perspectives on Organizational Fit; Ostroff, C., Judge, T.A., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 209–258. [Google Scholar]

- Greguras, G.J.; Diefendorff, J.M. Different fits satisfy different needs: Linking person-environment fit to employee commitment and performance using self-determination theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.; Lee, C.; Wang, H. Organizational inducements and employee citizenship behavior: The mediating role of perceived insider status and the moderating role of collectivism. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M.A.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.W. Servant leadership and innovative behavior: An empirical analysis of Ghana’s manufacturing sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stamper, C.L.; Masterson, S.S. Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, A.E.; Shen, C.T.; Chuang, A. Person-organization and person-supervisor fits: Employee commitments in a Chinese context. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 906–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, J.R. Person-environment fit in organizations: An assessment of theoretical progress. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 167–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Parks-Leduc, L. Selection for fit. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personal. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, M.; Schwartz, S.; Alessandri, G.; Döring, A.K.; Castellani, V.; Caprara, M.G. Stability and change of basic personal values in early adulthood: An 8-year longitudinal study. J. Res. Personal. 2016, 63, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verquer, M.L.; Beehr, T.A.; Wagner, S.H. A meta-analysis of relations between person-organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Bynum, B.H.; Piccolo, R.F.; Sutton, A.W. Person-organization value congruence: How transformational leaders influence work group effectiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masterson, S.S.; Stamper, C.L. Perceived organizational membership: An aggregate framework representing the employee-organization relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, J.R.; Smith, B.R.; Sprinkle, T.A. Clarifying the relational ties of organizational belonging: Understanding the roles of perceived insider status, psychological ownership, and organizational identification. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.M.; Shen, Y.; Chong, S. A dual-stage moderated mediation model linking authoritarian leadership to follower outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyne, L.; Pierce, J.L. Psychological ownership and feelings of possession: Three field studies predicting employee attitudes and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J.N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dai, L.; Chen, Y. A systematic review of perceived insider status. J. Hum. Resour. Sustain. Stud. 2015, 3, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hewlin, P.F.; Dumas, T.L.; Burnett, M.F. To thine own self be true? Facades of conformity, values incongruence, and the moderating impact of leader integrity. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littleford, C.; Ryley, T.J.; Firth, S.K. Context, control and the spillover of energy use behaviors between office and home settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schneider, B.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Macey, W.H. Organizational climate and culture. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, L.R.; Choi, C.C.; Ko, C.H.E.; McNeil, P.K.; Minton, M.K.; Wright, M.A.; Kim, K.I. Organizational and psychological climate: A review of theory and research. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2008, 17, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Chen, I.H.; Chang, P.C. Sense of calling in the workplace: The moderating effect of supportive organizational climate in Taiwanese organizations. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chiaburu, D.S.; Kirkman, B.L. Cross-level influences of empowering leadership on citizenship behavior Organizational support climate as a double-edged sword. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1076–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.E.; Rosen, C.C.; Richardson, H.A.; Williams, L.J.; Johnson, R.E. A new perspective on method variance: A measure-centric approach. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 855–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dollard, M.F.; Bakker, A.B. Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morrison, E.W.; Wheeler-Smith, S.L.; Kamdar, D. Speaking up in groups: A cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 89, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBreton, J.M.; Senter, J.L. Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 11, 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.E. Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 2005, 8, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. How do socio-demographic and psychological factors relate to households’ direct and indirect energy use and savings? J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén and Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Selig, J.P.; Preacher, K.J. Monte Carlo Method for Assessing Mediation: An Interactive Tool for Creating Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects [Computer Software]. 2008. Available online: http://www.quantpsy.org (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Preacher, K.J.; Selig, J.P. Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Commun. Methods Meas. 2012, 6, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, H.; Guan, Y.; Wu, C.H.; Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.; Yao, X. A relational model of perceived overqualification: The moderating role of interpersonal influence on social acceptance. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 3288–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R.; Lülfs, R. Legitimizing negative aspects in GRI-oriented sustainability reporting: A qualitative analysis of corporate disclosure strategies. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hoever, I.J. Research on workplace creativity: A review and redirection. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wee, Y.S.; Quazi, H.A. Development and validation of critical factors of environmental management. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2005, 105, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamper, C.L.; Masterson, S.S.; Knapp, J. A typology of organizational membership: Understanding different membership relationships through the lens of social exchange. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2009, 5, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.A.; Hasnan, N.; Osman, N.H. Environmental issues and corporate performance: A critical review. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 2, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.G.M.; Hong, P.; Modi, S.B. Impact of lean manufacturing and environmental management on business performance: An empirical study of manufacturing firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 129, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Cable, D.M.; Williamson, I.O.; Lambert, L.S.; Shipp, A.J. The phenomenology of fit: Linking the person and environment to the subjective experience of person-environment fit. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 802–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Billsberry, J. Fit for the future. In Organizational Fit: Key Issues and New Directions; Kristof–Brown, A.L., Billsberry, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, A.; Hsu, R.S.; Wang, A.C.; Judge, T.A. Does West “fit” with East? In search of a Chinese model of person-environment fit. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 480–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farh, J.L.; Tsui, A.S.; Xin, K.; Cheng, B.S. The influence of relational demography and guanxi: The Chinese case. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | χ2 | df | Δχ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized 4-factor model (EOF, PIS, GOC, VGB) | 328.81 | 164 | — | 0.05 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.01 |

| Alternative 3-factor model (EOF + PIS, GOC, VGB) | 402.08 | 167 | 73.27 *** (3) | 0.06 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.01 |

| Alternative 3-factor model (EOF, GOC, PIS + VGB) | 469.92 | 167 | 141.11 *** (3) | 0.07 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.01 |

| Alternative 3-factor model (EOF, PIS, GOC + VGB) | 537.96 | 167 | 209.15 *** (3) | 0.07 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.01 |

| Alternative 2-factor model (EOF + PIS, GOC + VGB) | 602.30 | 169 | 273.22 *** (5) | 0.08 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.01 |

| Alternative 2-factor model (EOF + PIS + VGB, GOC) | 616.15 | 169 | 287.34 *** (5) | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.01 |

| Alternative 1-factor model (EOF + PIS + GOC + VGB) | 711.61 | 170 | 382.80 *** (6) | 0.09 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.01 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.62 | 0.49 | — | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 35.72 | 9.45 | −0.04 | — | |||||||

| 3. Education | 1.83 | 0.72 | 0.05 | −0.35 *** | — | ||||||

| 4. Organizational tenure | 11.22 | 8.99 | −0.02 | 0.86 *** | −0.36 *** | — | |||||

| 5. Environmental attitude | 3.90 | 0.71 | 0.01 | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | 0.12 * | (0.86) | ||||

| 6. Employee-organization fit | 4.20 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.14 ** | 0.05 | 0.10 * | 0.46 *** | (0.91) | |||

| 7. Perceived insider status | 4.24 | 0.77 | 0.12* | 0.17 *** | 0.03 | 0.21 *** | 0.11 * | 0.32 *** | (0.76) | ||

| 8. Green organizational climate | 4.17 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.22 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.27 *** | (0.91) | |

| 9. Voluntary green behavior | 4.38 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.24 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.28 *** | (0.88) |

| Variables | Main Effect | Mediation Effect | Moderation Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Green Behavior | Perceived Insider Status | Voluntary Green Behavior | Voluntary Green Behavior | |

| Intercept | 3.84 *** (0.15) | 3.97 *** (0.21) | 2.56 *** (0.23) | 3.94*** (0.18) |

| Control variables | ||||

| Gender | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.17 ** (.06) | -0.01 (0.06) | −0.03 (0.08) |

| Age | −0.01 *** (0.00) | −0.01 (0.01) | -0.01 ** (0.00) | −0.01 ** (0.00) |

| Education | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.10 * (0.05) | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.01 (0.10) |

| Organizational tenure | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 *** (0.01) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Environmental attitude | 0.16 * (0.10) | −0.07 *** (0.02) | 0.18 * (0.10) | 0.18 (0.09) |

| Main predictors | ||||

| Employee-organization fit | 0.20 ** (0.07) | 0.30 *** (0.03) | 0.10 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.06) |

| Perceived insider status | 0.33 *** (0.03) | 0.33 *** (0.03) | ||

| Green organizational climate | 0.12 * (0.06) | |||

| Interaction | ||||

| Perceived insider status ×Green organizational climate | 0.17 *** (0.02) | |||

| Monte Carlo 95% CI | (0.08, 0.12) | |||

| Outcome | Moderator | Stage | Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Organizational Climate | First (Pmx) | Second (Pym) | Indirect (Pmx × Pym) | 95% CI of Indirect Effect | |

| Voluntary green behavior | High (+1 SD) | 0.30 *** (0.03) | 0.41 *** (0.03) | 0.12 *** (0.01) | (0.10, 0.15) |

| Low (−1 SD) | 0.30 *** (0.03) | 0.25 *** (0.03) | 0.08 *** (0.01) | (0.05, 0.10) | |

| Difference | — | 0.16 *** (0.02) | 0.05 *** (0.003) | (0.04, 0.06) | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, J.; Mao, J.-Y.; Huang, S.; Qing, T. Employee-Organization Fit and Voluntary Green Behavior: A Cross-Level Model Examining the Role of Perceived Insider Status and Green Organizational Climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2193. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072193

Xiao J, Mao J-Y, Huang S, Qing T. Employee-Organization Fit and Voluntary Green Behavior: A Cross-Level Model Examining the Role of Perceived Insider Status and Green Organizational Climate. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(7):2193. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072193

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Jincen, Jih-Yu Mao, Sihao Huang, and Tao Qing. 2020. "Employee-Organization Fit and Voluntary Green Behavior: A Cross-Level Model Examining the Role of Perceived Insider Status and Green Organizational Climate" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2193. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072193