Educational Interventions for Nursing Students to Develop Communication Skills with Patients: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

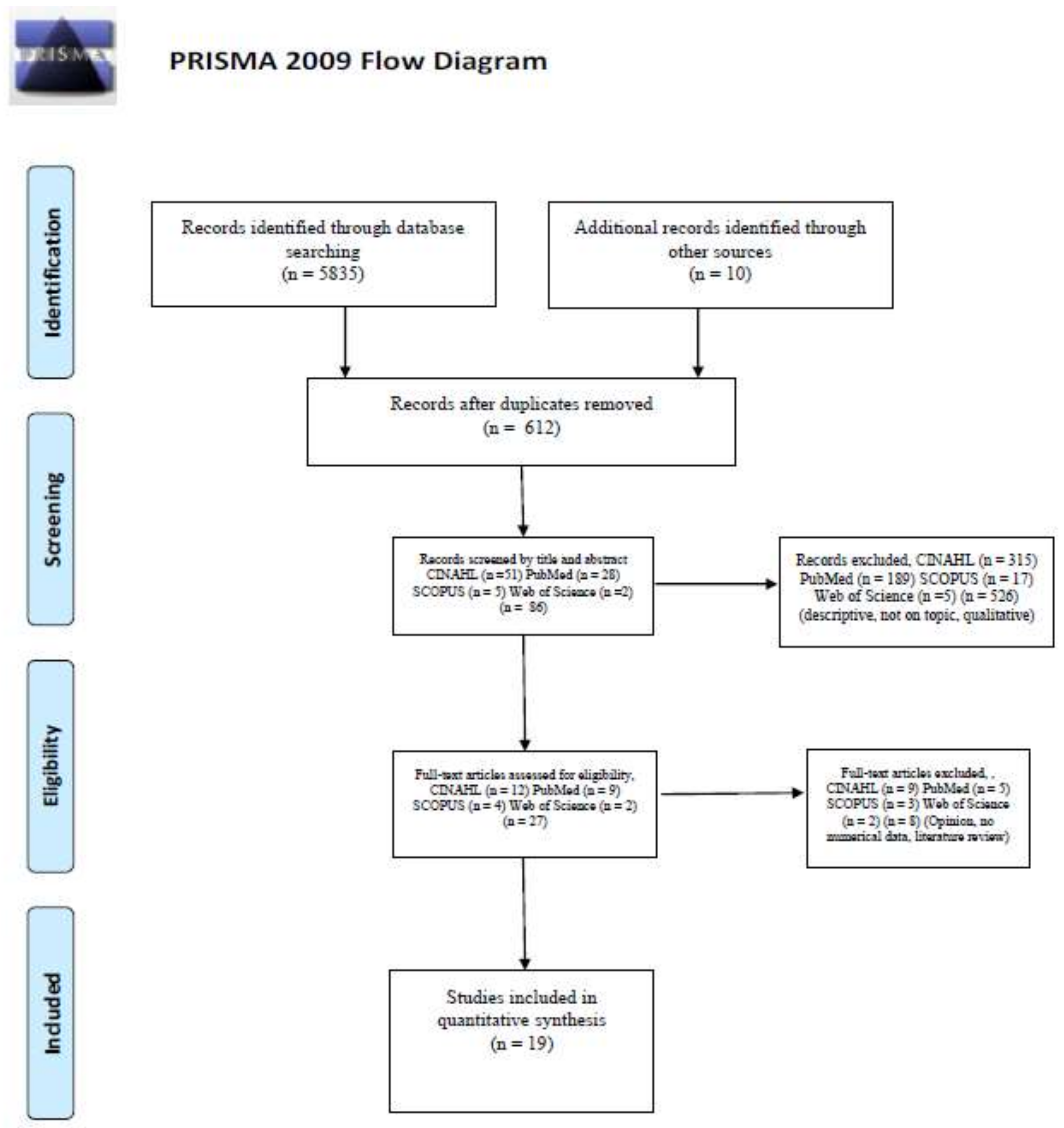

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data extraction

2.3. Quality appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study

3.2. Theoretical frameworks

3.3. Intervention characteristics

3.4. Outcome measures

3.5. Intervention impact on outcomes

3.6. Quality assessment

4. Discussion

Strengths and limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosenberg, S.; Gallo-Silver, L. Therapeutic communication skills and student nurses in the clinical setting. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2011, 6, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peplau, H. Interpersonal Relations in Nursing: A Conceptual Frame of Reference for Psychodynamic Nursing; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cusatis, R.; Holt, J.M.; Williams, J.; Nukuna, S.; Asan, O.; Flynn, K.E.; Neuner, J.; Moore, J.; Crotty, B.H. The impact of patient-generated contextual data on communication in clinical practice: A qualitative assessment of patient and clinician perspectives. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makoul, G.; Krupat, E.; Chang, C.H. Measuring patient views of physician communication skills: Development and testing of the Communication Assessment Tool. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 67, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolrahimi, M.; Ghiyasvandian, S.; Zakerimoghadam, M.; Ebadi, A. Antecedents and Consequences of Therapeutic Communication in Iranian Nursing Students: A Qualitative Research. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2017, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ryan, C.A.; Walshe, N.; Gaffney, R.; Shanks, A.; Burgoyne, L.; Wiskin, C.M. Using standardized patients to assess communication skills in medical and nursing students. BMC Med. Educ. 2010, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hsu, L.L.; Chang, W.H.; Hsieh, S.I. The effects of scenario-based simulation course training on nurses’ communication competence and self-efficacy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Prof. Nurs. 2015, 31, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Tietsort, C.; Posteher, K.; Michaelides, A.; Toro-Ramos, T. Enabling Self-management of a Chronic Condition through Patient-centered Coaching: A Case of an mHealth Diabetes Prevention Program for Older Adults. Health Commun. 2019, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, C. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care; National Consensus Project: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, B.B.; Rodzen, L.; Spross, G. Raising the SBAR: How better communication improves patient outcomes. Nursing 2008, 38, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghee, S.; Lotfabadi, M.K.; Salarhaji, A.; Vaghei, N.; Hashemi, B.M. Comparing the Effects of Contact-Based Education and Acceptance and Commitment-Based Training on Empathy toward Mental Illnesses among Nursing Students. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2018, 13, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excelence. End of Life Care for Infants, Children and Young People with Life-Limiting Conditions: Planning and Management 2016. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng61/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Alasad, J.; Ahmad, M. Communication with critically ill patients. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, B.A.; Kothe, E.J. Evaluating a nursing communication skills training course: The relationships between self-rated ability, satisfaction, and actual performance. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2010, 10, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neilson, S.J.; Reeves, A. The use of a theatre workshop in developing effective communication in pediatric end of life care. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 36, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, S.; Perry, R.; Blanchard, K.; Linsell, L. Effectiveness of a three-day communication skills course in changing nurses’ communication skills with cancer/palliative care patients: A randomised controlled trial. Palliat. Med. 2008, 22, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, F.; Balouchi, A.; Shahsavani, A. Investigation of nursing students’ verbal communication quality during patients’ education in zahedan hospitals: Southeast of Iran. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2016, 8, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhana, V.M. Interpersonal skills development in Generation Y student nurses: A literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 1430–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heidari, H.; Mardani Hamooleh, M. Improving communication skills in clinical education of nursing students. J. Client Cent. Nurs. Care 2015, 1, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shafakhah, M.; Zarshenas, L.; Sharif, F.; Sarvestani, R.S. Evaluation of nursing students’ communication abilities in clinical courses in hospitals. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 7, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, R.M.; Fiscella, K.; Lesser, C.S.; Stange, K.C. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.H.; Callister, L.C.; Berry, J.A.; Dearing, K.A. Patient-centered care and adherence: Definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2008, 20, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0; Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK; Jonh Wiley & Sons Ltd: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 Edition; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, L.M.; Mullen, L.K. Expanding nursing simulation programs with a standardized patient protocol on therapeutic communication. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 38, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merriam, S.B.; Cafferella, R.S.; Baumgartner, L.M. Learning in Adulthood a Comprehensive Guide, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, S.; Kowitlawakul, Y.; Devi, M.K.; Chen, H.C.; Soong, S.K.A.; Ang, E. Blended Learning Pedagogy designed for Communication Module among Undergraduate Nursing Students: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 61, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Herrington, J.; Reeves, T.; Oliver, R. A Guide to Authentic E-Learning; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K.L.; Rose, L.E.; Berg, J.B.; Park, H.; Shatzer, J.H. The Teaching Effectiveness of Standardized Patients. J. Nurs. Educ. 2006, 45, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomfield, J.G.; O’Neill, B.; Gillett, K. Enhancing student communication during end-of-life care: A pilot study. Palliat. Supportive Care 2015, 13, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylle, D. In-simulation Debriefing Increases Therapeutic Communication Skills. Nurs. Educ. 2019, 44, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Ko, E.; Lee, E.S. Effects of simulation-based education on communication skill and clinical competence in maternity nursing practicum. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2012, 18, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, E.C.L.; Chen, S.L.; Chao, S.Y.; Chen, Y.C. Using standardized patient with immediate feedback and group discussion to teach interpersonal and communication skills to advanced practice nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.T.; Chanda, N. Mental Health Clinical Simulation: Therapeutic Communication. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2016, 12, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, E.; Kutlu, F.Y.; Ates, E. The Effect of Standardized Patient Simulation Prior to Mental Health Rotation on Nursing Students’ Anxiety and Communication Skills. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 41, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D. Using Standardized Patients to teach Therapeutic Communication in Psychiatric Nursing. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2014, 10, e81–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, T.; Blake, T. Improving Therapeutic Communication in Nursing through Simulation Exercise. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2019, 14, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.Y. Training Nursing Students’ Communication Skills with Online video peer Assessment. Comput. Educ. 2016, 97, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghcheghi, N.; Koohestani, H.R.; Rezaei, K. A comparison of the cooperative learning and traditional learning methods in theory classes on nursing students’ communication skill with patients at clinical settings. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, M.S.; Park, H.R. Effects of case-based learning on communication skills, problem-solving ability, and learning motivation in nursing students. Nurs. Health Sci. 2015, 17, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, K.H.; An, G.J. Effect of end-of-life Care Education using Humanistic Approach in Korea. Collegian 2015, 22, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.; Wang, W. Development and evaluation of a learner-centered training course on communication skills for baccalaureate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.; Wang, W. Development and Evaluation of a learner-centered educational Summer Camp Program on Soft Skills for baccalaureate nursing students. Nurse Educ. 2014, 39, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, R.; Hasanpour-Dehkordi, A.; Shakhaei, S.; Motaarefi, H. The Effects of Teaching Communication Skills to Nursing Students on the Quality of Care for Patients. Asian J. Pharm. 2018, 12, S1252–S1255. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E.; Goldsmith, J.; Richardson, B.; Hallett, J.S.; Clark, R. The practical nurse: A case for COMFORT communication training. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2013, 30, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.N.; Park, S.C.; Yoo, S.W.; Shen, H. Mapping health communication scholarship: Breadth, depth, and agenda of published research in health communication. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Esparcia, A.; Castillero-Ostio, E. Communication research. Methodologies, themes and sources. Rev. Int. Rel. Public. 2019, 18, 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Reidl-Martínez, L.M. Marco conceptual en el proceso de investigación. Invest. Educ. Med. 2012, 1, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Cant, R.; Lapkin, S. A systematic review of the effectiveness of empathy education for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 75, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacLean, S.; Kelly, M.; Geddes, F.; Della, P. Use of simulated patients to develop communication skills in nursing education: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 48, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Foronda, C.; Liu, S.; Bauman, E.B. Evaluation of simulation in undergraduate nurse education: An integrative review. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013, 9, e409–e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, P.J.; Jeon, K.D.; Koh, M.S. The effects of simulation-based learning using standardized patients in nursing students: A meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e6–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INACSL Standards Committee. INACSL Standards of best practice: Simulation. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013, 12, S1–S50. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K.L.; Bohnert, C.A.; Gammon, W.L.; Hölzer, H.; Lyman, L.; Smith, C.; Thompson, T.M.; Wallace, A.; Gliva-McConvey, G. The association of standardized patient educators (ASPE) standards of best practice (SOBP). Adv. Simul. 2017, 2, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, M.A.; Hagle, H.; Puskar, K.; Knapp, E.; Kane, I.; Lindsay, D.; Terhorst, L.; Mitchell, A.M. Creative learning through the use of simulation to teach nursing students screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for alcohol and other drug use in a culturally competent manner. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2018, 29, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplonyi, J.; Bowles, K.A.; Nestel, D.; Kiegaldie, D.; Maloney, S.; Haines, T.; Williams, C. Understanding the impact of simulated patients on health care learners’ communication skills: A systematic review. Med. Educ. 2017, 51, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Rowe, J.; Watson, K.; Hitchen-Holmes, D. Graduating nurses’ self-efficacy in palliative care practice: An exploratory study. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, A.; Harrison, P.; Rowe, J.; Edwards, S.; Barnes, M.; Henderson, S. Students take the lead for learning in practice: A process for building self-efficacy into undergraduate nursing education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018, 31, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oyelana, O.; Martin, D.; Scanlan, J.; Temple, B. Learner-centred teaching in a non-learner-centred world: An interpretive phenomenological study of the lived experience of clinical nursing faculty. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 67, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chicca, J.; Shellenbarger, T. Connecting with Generation Z: Approaches in nursing education. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2018, 13, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repsha, C.L.; Quinn, B.L.; Peters, A.B. Implementing a Concept-Based Nursing Curriculum: A Review of the Literature. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2020, 15, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatto, B.; Shagavah, A.; Krieger, M.; Lutz, L.; Duncan, C.E.; Wagner, E.K. Active learning outcomes on NCLEX-RN or standardized predictor examinations: An integrative review. J. Nurs. Educ. 2019, 58, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarikoc, G.; Ozcan, C.T.; Elcin, M. The impact of using standardized patients in psychiatric cases on the levels of motivation and perceived learning of the nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 51, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Reddy, P.; Marshall, S.; Beovich, B.; McKarney, L. Simulation and mental health outcomes: A scoping review. Adv. Simul. 2017, 2, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Øgård-Repål, A.; De Presno, Å.K.; Fossum, M. Simulation with standardized patients to prepare undergraduate nursing students for mental health clinical practice: An integrative literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 66, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.A. Cue-responding during simulated routine nursing care: A mixed method study. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; Wolter Kluwer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Order Number | 1st Author, Date (Country) | MAStARI | Participants | Objetives | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Becker et al. 2006 [31] (USA) 1C | 10 | n = 147 nursing students enrolled in a psychiatric nursing course (IG = 58; CG = 89). | To evaluate knowledge of depression and therapeutic communication skills SP. | Desing: randomized control group. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 2 | Baghcheghi et al. 2011 [41] (Iran) 2C | 7 | N = 34 sophomore nursing students (16 IG; 18 CG). | To evaluate the effect of tradicional learning and cooperative learning methods on nursing students´communication with patients. | Design: Experimental, observer-blinder two groups study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 3 | Kim et al. 2012 [34] (Korea) 2C | 7 | n = 70 sophomores nursing students enrolled in a theoretical course in maternity. | To determine the effect of simulation-based education on the communication skill and clinical competence of nursing students in maternity nursing practicum. | Design: quasi-experimental study, two gropup study. Data Collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 4 | Wittenberg-Lyles et al. 2012 [47] (USA) 2D | 7 | n = 32 nursing students. | To assess the effects of communication training for the practical nurse. | Design: quasi-experimental pilot study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 5 | Jo and An 2013 [43] (Korea) 2C | 7 | n = 39 nursing students (19 IG; 20 GC) from two universities. | To examine the effects of a humanistic end-of-life care course on South Korean undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes toward death, death anxiety, and communication skills. | Design: quasi-experimental two group study. Data collection: Pre-test, post-test. |

| 6 | Lau and Wang 2013 [44] (China) 2D | 7 | n = 62 fourth-year nursing students enrolled CST course. | To develop a learner-centered Communication Skills Training (CST) course; (2) to evaluate the course by comparing scores for communication skills, clinical interaction, interpersonal dysfunction, and social problem-solving ability. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study, two-phase mixed methods Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 7 | Lin et al. 2013 [35] (Taiwan) 1C | 9 | n = 26 first year nursing students (14 IG; 12 CG). | To examine the effectiveness of using SP with SP feedback and group discussion to teach Interpersonal and communication skills (IPCS) in nursing education. | Desing: Randomized Controlled Study two group. Data collection: pre-tets, post-test. |

| 8 | Lau and Wang 2014 [45] (China) 2D | 7 | n = 59 fourth-year nursing students attended the summer camp program. | To develop a learner-centered educational summer camp program for nursing students and to evaluate the effectiveness of the camp program on enhancing the participants’ communication skills. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study, two-phase mixed methods. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 9 | Webster 2014 [38] (USA) 2D | 7 | n = 89 senior baccalaureate nursing students enrolled in a psychiatric clinical course. | To determine the effectiveness of SPEs as a teaching modality to improve nursing students’ use of therapeutic communication skills with individuals with mental illness. | Design: quasi-experimental, one group study. Data Collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 10 | Bloomfield et al. 2015 [32] (UK) 2D | 6 | n = 28 second-year nursing students and fourth-year medical students from a population of N = 180 nursing students and N = 450 medical students. | To design, implement, and evaluate an educational intervention employing simulated patient actors to enhance students’ abilities to communicate with dying patients and their families. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study, two-phase mixed methods. Data Collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 11 | Yoo and Park 2015 [42] (Korea) 2C | 7 | n = 143 (72 IG; 71 CG) sophomore undergraduate nursing student enrolled in a mandatory health communication course from a population of N = 151. | To evaluate the effectiveness of Case-based learning on undergraduate nursing students in the health communication course. | Design: quasi-experimental two group study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 12 | Lai 2016 [40] (Taiwan) 2D | 7 | n = 50 quasi-experimental single group study. | To implement an online video peer assessment system to scaffold their communication skills and to examine the effects and validity of the peer assessment. | Desing: quasi-experimental single group study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 13 | Martin and Chanda 2016 [36] (USA) 2D | 8 | n = 28 prelicensure nursing students enrolled in a mental health nursing theory and clinical course. | To introduce therapeutic communication simulations with emphasis on symptoms related to psychiatric disorders as a part of mental health theory and clinical courses. | Design: quasi-experimental, one group. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 14 | Taghizadeh et al. 2017 [46] (Iran) 2D | 8 | n = 66 last year nursing students and n = 132 patients. | To determine the impact of teaching communication skills to nurse students on the quality of care given by nursing students. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study. Data collection: pre-test, post- test. |

| 15 | Shorey et al. 2018 [28] (China) 2D | 8 | n = 124 first-year undergraduate nursing students enrolled in the nursing course. | To evaluate the effectiveness of blended learning pedagogy in a redesigned communication module among nursing undergraduates in enhancing their satisfaction levels and attitudes towards learning communication module as well as self-efficacy in communication. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study. Data Collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 16 | Blake and Blake 2019 [39] (USA) 2D | 5 | n = 32 nursing students in their capstone course from a population of N = 35. | To examine the effects of a nursing lab simulation used to increase the self-efficacy of nursing students with their ability to use effective communication. | Design: quasi-experimental single group. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 17 | Donovan and Mullen 2019 [26] (USA) 2D | 7 | n = 116 undergraduate nursing students registered for three successive mental health nursing courses during academic year from a population of N = 160 (RR 72.5%). | To examine the efficacy of learned classroom therapeutic communication techniques applied to a standardized patient mental health simulated experience. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 18 | Gaylle 2019 [33] (USA) 2C | 7 | n = 65 senior students enrolled in a psychiatric clinical rotation at a public university from a population of N = 67 (RR 97%). (IG = 32; CG = 33). | To explored the effects of in-simulation and postsimulation debriefing on students’ knowledge, performance, anxiety, and perceptions of the debriefing process. | Design: quasi-experimental, two group study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. |

| 19 | Ok et al. 2019 [37] (Turkey) 2C | 6 | n = 85 third-year nursing students enroled in a course on mental health and psychiatric at two different universities from a population of N = 103 (RR 82.5%). (IG = 52; CG = 33) | To measure the impact of using standardized patient simulation (SPS) prior to clinical practice on the anxiety levels and communication skills. | Design: quaxi-experimental two group Data collection: pre-test, post-test |

| Order Number | 1st Author, Date (Country) | Participants | Study Design | Theoretical Framework | Intervention | Quantitative Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Becker et al. 2006 [31] (USA) | n = 147 nursing students enrolled in a psychiatric nursing course (IG = 58; CG = 89). | Design: randomized control group. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Simulation—using Standardized Patient (SP). Lectures on therapeutic communication and nursing care of clients with depression (both group), Interview SP, debriefing, videotape self-analysis with accompanying handbook. Duration: once a week, 7 weeks. Interview SP (30 min), debriefing (30 min), videotape self-analysis (after 1 week of the SP encounter). CG - usual classroom lecture format. | Students: Communication Knowledge Test (CKT), developed by the authors for this study. Student Self-Evaluation of SP Encounter (SSPE), developed by the authors for this study. Patients: SP checklist, developed by the authors for this study. Standardized Patient Interpersonal Ratings (SPIR), developed by the authors for this study. |

| 2 | Baghcheghi et al. 2011 [41] (Iran) | N = 34 sophomore nursing students (16 IG; 18 CG). | Design: Experimental, observer-blinder two groups study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Cooperative learning methods. (work in group) Activities included in lectures: Socratic questioning, paired discussion of homework assignments, paired pop quizzes, small group discussion of case scenarios, paired concept-map generation exercises, student identification of examples for concepts being discussed, and think-pair-share exercises. Each group would be responsible for presenting a 15 to 20-minute review of information from their particular content category to the class. Throughout the semester the group members evaluated each other with a weekly evaluation tool; feedback. Duration: one semester. CG—usual classroom lecture format. | Nursing Students’ communication with patient scale. |

| 3 | Kim et al. 2012 [34] (Korea) | n = 70 sophomores nursing students enrolled in a theoretical course in maternity. | Design: quasi-experimental study, two group study. Data Collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned | Simulation—using high-fidelity patient simulator. Duration: 9 h over three weeks (briefing, simulation lab, debriefing). CG—usual classroom lecture format. | Communication Skills Tool. Clinical Competence Tool (CCT). |

| 4 | Wittenberg-Lyles et al. 2012 [47] (USA) | n = 32 nursing students. | Design: quasi-experimental pilot study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned | COMFORT communication and consulting course. interactive, educational training session and taught students using a combination of PowerPoint lectures, case studies, small group discussions, and exercises. Students were exposed to concepts including narrative clinical practice, person-centered messages, the task and relational components in all interactions, and participated in 3 encounters using these concepts. Duration: 3h. | Course Experience Questionnarie (CEQ) created by authors for this study. Perceived Importance of Medical Communication (PIMC). Communication Skill Attitude Scale (CSAS). Caring Self-Efficacy Scale (CES). |

| 5 | Jo and An 2013 [43] (Korea) | n = 39 nursing students (19 IG; 20 GC) from two universities. | Design: quasi-experimental two group study. Data collection: Pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | End-of-life- Care course teaching included uses humanistic educational methods such as lectures, group discussion, watching a movie, analysis of novel and poem, appreciation of music, and collage art, role-play, and sharing personal experiences. Duration: 2h x 16 weeks. CG—usual classroom lecture format. | Attitudes toward death. Death Anxiety Scale (DAS). Communication Assessment Tool (CAT). |

| 6 | Lau and Wang 2013 [44] (China) | n = 62 fourth-year nursing students enrolled CST course. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study, two-phase mixed methods Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Communication Skills Training (CST) course. Included theoretical lectures and practical components (Immediate feedback; Role Playing; Group discussion; didactical games). Duration: two day, 8 h per day. | Communication Ability Scale (CAS) Clinical Interaction Scale (CIS). Interpersonal Dysfunction Checklist (IDC). Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised (C-SPSI-R). |

| 7 | Lin et al. 2013 [35] (Taiwan) | n = 26 first year nursing students (14 IG; 12 CG). | Design: Randomized Controlled Study two group. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Simulation - using SP. Briefing; scenario demonstration; role-playing. Duration: 2-day (SP assessments with SP feedback and group discussion). CG—usual classroom lecture format. | Interpersonal Communication Skills (IPCS) assessment tool. Student Learning Satisfaction (SLS) Scale. |

| 8 | Lau and Wang 2014 [45] (China) | n = 59 fourth-year nursing students attended the summer camp program. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study, two-phase mixed methods. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned | Educational Summer Camp Program on Communication Skills—three sharing sessions and five experimental learning games. Sharing sessions on self-exploration, teambuilding, and clinical interaction. Experiential learning games were used as learning strategies (icebreaker, self-discovery, team building, problem solving, and communication). Duration: 3 days | Communication Ability Scale (CAS) Clinical Interaction Scale (CIS). Interpersonal Dysfunction Checklist validated Chinease (IDC). Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R). |

| 9 | Webster 2014 [38] (USA) | n = 89 senior baccalaureate nursing students enrolled in a psychiatric clinical course. | Design: quasi-experimental, one group study. Data Collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mecioned. | Simulation—using SP, simulations were video-recorded, watched their video and conducted a self-reflection of strengths and areas for improvement; debriefing conducted by faculty using a problem-based learning approach. Duration: Two SPEs, one at the beginning of the semester and one at the end of the semester. 15–20 min sessions. | The effectiveness of the use of SPEs to teach therapeutic communication skills in psychiatric nursing ckecklist created by author for this study. Feedback from faculty ckecklist created by author for this study. |

| 10 | Bloomfield et al. 2015 [32] (UK) | n = 28 second-year nursing students and fourth-year medical students from a population of N = 180 nursing students and N = 450 medical students. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study, two-phase mixed methods. Data Collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Simulation—using SP (two scenarios), pre-briefing; simulation; debrief. Duration: 45 min including pre-brief, simulation and debrief. | students’ perceived levels of confidence, competence, and concern when communicate with dying patients and their families questionnaire created by authors for this study. |

| 11 | Yoo and Park 2015 [42] (Korea) | n = 143 (72 IG; 71 CG) sophomore undergraduate nursing student enrolled in a mandatory health communication course from a population of N = 151. | Design: quasi-experimental two group study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mencioned. | Case-Based Learning (CBL) - as teaching activity in a course. Five authentic cases of patient-nurse communication. (Stage of each 5-Cases: Case presentation; Student´s case analysis individually; group discussion and analysis; finding proper solution by group; group presentation of the cases). Duration: 28 h. CG –traditional lecture-based learning. | Communication Assessment Tool (CAT). Problem-Solving Inventory (PSI). Instructional Materials Motivation Scale (IMMS). |

| 12 | Lai 2016 [40] (Taiwan) | n = 50 quasi-experimental single group study. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Simulation—using SP an online video peer assessment system. Recorded therapeutic consultation with a SP and uploaded to YouTube; peer assessment and feedback through a web-based assessment system; expert evaluation (two rounds; different scenarios). Duration: SP twice; once in the mid-term exam week and the other in the final exam week. Duration not stated. | Interpersonal Communication Assessment Scale (ICAS). |

| 13 | Martin and Chanda 2016 [36] (USA) | n = 28 prelicensure nursing students enrolled in a mental health nursing theory and clinical course. | Design: quasi-experimental, one group. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Simulation using SP (three stations; two simulation sessions). Briefing; simulation with two standardized patients and a case study; debriefing. Duration: 40-50 min simulation followed by an hour debriefing. | Confidence with Communication Skill Scale. Therapeutic communication and nontherapeutic communication techniques, checklist created by authors, with the purpose of evaluating skills that would occur during the SP encounters. |

| 14 | Taghizadeh et al. 2017 [46] (Iran) | n = 66 last year nursing students and n = 132 patients. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study. Data collection: pre-test, post- test. | Not mentioned. | Communication Training Course. lectures and workshops using educational equipment and technology. Duration: 6 h. | Student´s Communication skills checklist created by the authors for this study. Quality of Care Questionnaire for Patients. |

| 15 | Shorey et al. 2018 [28] (China) | n = 124 first-year undergraduate nursing students enrolled in the nursing course. | Design: quasi-experimental single group study. Data Collection: pre-test, post-test. | Bandura´s self-efficacy theory (1997). | Blended learning environment face-to-face each week for tutorials (Role-playing and problem-based learning); lecture materials online (breeze presentations, PowerPoints slides, and multi-media components, delivered) online quizzes, discussion forums, and reflection exercises; assessment (analyzing real life clinical scenarios by creating online videos; interview with SP). Duration: 13 weeks. Four modular credit x 10 h (2–3 h for face-to-face tutorial or lecture and 7–8 h for the self-directed learning). | Blended Learning Satisfaction Scale (BLSS). Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS). Communication Skills subscale of the Nursing Students Self-Efficacy Scale (C-NSSES). |

| 16 | Blake and Blake 2019 [39] (USA) | n = 32 nursing students in their capstone course from a population of N = 35. | Design: quasi-experimental single group. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Simulation—role-playing, debriefing Duration: a week. | Self-efficacy related to therapeutic communication, developed by the authors for this study. A rubric for therapeutic and nontherapeutic statements or actions developed by the authors for this study. |

| 17 | Donovan and Mullen 2019 [26] (USA) | n = 116 undergraduate nursing students registered for three successive mental health nursing courses during academic year from a population of N = 160 (RR 72.5%). | Design: quasi-experimental single group study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Constructivist learning theory (Merriam et al. 2012). | Simulation—using SP. Lectures on therapeutic communication techniques, which included readings, video clips with discussion; simulation; debriefing. Duration: 60 min including briefing, simulation and debriefing. | Confidence Simulation, with a dimension about level of confidence of learned therapeutic communication skills. |

| 18 | Gaylle 2019 [33] (USA) | n = 65 senior students enrolled in a psychiatric clinical rotation at a public university from a population of N = 67 (RR 97%). (IG = 32; CG = 33). | Design: quasi-experimental, two group study. Data collection: pre-test, post-test. | Not mentioned. | Simulation—using SP (four scenarios) briefing; simulation; In simulation-debriefing. Duration: one week. CG - briefing, simulation, postsimulation debriefing. | Students’ knowledge of psychiatric assessment. Therapeutic communication checklist created by author. Students’ perceived anxiety related to a psychiatric clinical practicum created by author. Perceptions of the debriefing experience checklist created by author for this study. |

| 19 | Ok et al. 2019 [37] (Turkey) | n = 85 third-year nursing students enrolled in a course on mental health and psychiatric at two different universities from a population of N = 103 (RR 82.5%). (IG = 52; CG = 33) | Design: quasi-experimental two group Data collection: pre-test, post-test | Not mentioned. | Simulation—using SP theoretical lecture on communication skills and schizophrenia; simulation using SP, debriefing. Duration: 5 hours theoretical lectures, 10–12 min simulation, 30–35 min debriefing. CG—Theoretical lectures and clinical practices. | Communicational Skills Inventory (CSI) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) |

| Order Number | 1st Author, Date (Country) | Findings | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Becker et al. 2006 [31] (USA) | No significant differences were found between the two groups on measures of interpersonal skills, therapeutic communication skills, and knowledge of depression. | Further research is needed, this study support the use of SPs in nursing education for communication skills training. |

| 2 | Baghcheghi et al. 2011 [41] (Iran) | The results showed that no significant difference between the two groups in students’ communication skills scores before the teaching intervention (p > 0.05), but did show a significant difference between the two groups in the interaction skills and problem follow up sub-scales scores after the teaching intervention (p < 0.05). | This study provides evidence that cooperative learning is an effective method for improving and increasing communication skills of nursing students especially in interactive skills and follow up the problems sub-scale, thereby it is recommended to increase nursing students’ participation in arguments by applying active teaching methods which can provide the opportunity for increased communication skills. |

| 3 | Kim et al. 2012 [34] (Korea) | The communication skill score of the experimental group that participated in simulation-based education increased 0.58 points and the control group increased 0.09 points, indicating a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.020). The clinical competence score of the experimental group that participated in simulation-based education increased 0.63 points, and the score for the control group increased 0.15 points, indicating a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.009). | Simulation-based education in maternity is effective in promoting communication skill and clinical competence. |

| 4 | Wittenberg-Lyles et al. 2012 [47] (USA) | The practical nurses’ exposure to the COMFORT communication training allowed students to see its benefits, resulting in more positive attitudes to communication skills learning as measured by the CSAS (p < 0.000). The COMFORT communication curriculum also increased perceptions of the importance of communication in nurse training as assessed by the PIMC (p < 0.009). In addition, COMFORT training resulted in an increase in practical nurses’ reported self-efficacy in using communication skills with patients and families, although no statistically differences were found (p = 0.052). | This study shows promise for the feasibility and use of the CONFORT curriculum for nursing students communication training. |

| 5 | Jo and An 2013 [43] (Korea) | Attitudes toward death (p = 0.027) and communication skills (p = 0.008) appeared to have significantly increased in the experimental group. However, death anxiety (p = 0.984) did not significantly differ between the two groups after intervention. | The course is effective in reducing negative attitudes toward death and increasing the communication skills of nursing students. |

| 6 | Lau and Wang 2013 [44] (China) | There were significantly increase between students: the mean pre-test and post-test scores for communication ability (p = 0.015). there were improvement in the scores for content of communication and handling of communication barriers (p < 0.001). In addition, the training was practically important, as indicated by the effect size of 2.39 in the score for the handling of communication barriers. Although the scales of communication ability, clinical interaction, interpersonal dysfunction, and social problem solving were improved, they were not statistically significant (p >.05). | The course was effective in improving communication skills in nursing students. |

| 7 | Lin et al. 2013 [35] (Taiwan) | All participants expressed high SLS (94.44%) and showed significant (p ≤ 0.025) improvements on IPCS total scores, interviewing, and counseling. However, there were no significant differences between groups (p = 0.374). | Using SPs to teach IPCS to nursing students produced a high SLS, but future studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of SP feedback and group discussions. |

| 8 | Lau and Wang 2014 [45] (China) | The analysis showed a significant difference between the mean pretest and posttest scores of the subscales (p = 0.003) and total communication skills scores (p < 0.0001). There was a statistically significant increase in the cognition of communication scores from pre-test to post-test (p < 0.0001), content of communication (p = 0.009), and handling of communication barriers (p < 0.001). The mean pretest and posttest CIS total scores increased (p < 0.0001), sympathetic consideration (p < 0.0001), active listening (p = 0.001), and taking the initiative in care subscales (p = 0.009). The scores of positive problem orientation subscale of the SPSI-R improved (p = 0.037). | The Educational Summer Camp Program was effective in improving nursing students´communication skills. |

| 9 | Webster 2014 [38] (USA) | The students did not demonstrate significant improvement on 2 of the 14 evaluation criteria -approaching client with a nonthreatening body stance (p = 0.218) and introducing self (p = 0.74)- although there was improvement noted for the two evaluation criteria. There was improvement noted in anxiety, students’ ability to establish eye contact, to engage in efforts to put the patient at ease, safety assessments, the ability to set limits on inappropriate behavior (p < 0.05). In building a therapeutic relationship, Improvements were also noted in all three of these areas (using therapeutic communication techniques; responding appropriately to verbal statements and responding appropriately to nonverbal behavior), (p < 0.05). The ability to validate the meaning of a patient’s response increased significantly. Last, the appropriate termination were increase significantly for these two areas (summarizing content of interaction, terminating appropriately), (p < 0.05). | This study suggests that the use of SPEs is an effective methodology for promoting therapeutic communication skills in nursing students. |

| 10 | Bloomfield et al. 2015 [32] (UK) | After the simulation, self-perceived confidence levels when communicating with the family and friends of dying patients increased significantly (p < 0.05). The majority of students reported increased levels of competence when talking with the family of dying patients (p < 0.05). | Simulation was found to be an effective means of preparing nursing students to communicate with dying patients and their families. |

| 11 | Yoo and Park 2015 [42] (Korea) | A significant increase in the communication skills score of the intervention group was observed (p < 0.001) while a slight increase was observed for the control group (p < 0.001). There was a significant difference in the communication skills of the two groups (p < 0.001). A significant decrease in the problem solving ability score of the intervention group was observed (p < 0.001), whereas an increase was observed in the control group (p < 0.001). A significant improvement was observed for the problem-solving ability of the intervention group, as compared to the control group (p < 0.001). Finally, scores for learning motivation showed a significant increase (p < 0.001), for the intervention group, whereas a decrease (p > 0.05), was observed for the control group. Moreover, a significant difference was found in the learning motivation scores of the two groups (p < 0.001). | This finding suggests that case-based learning is an effective learning and teaching method. |

| 12 | Lai 2016 [40] (Taiwan) | The scores given by the peers were significatly corelated with those given by experts (r = 0.36, p<0.05). In relation, students’ attitudes toward the peer assessment activities. Overall, the mean scores of each item were greater than 4 (agree) which means the students were satisfied with the peer assessment learning activities. | The nursing students had improved their skills in therapeutic communication as a result of the networking peer assessment. Expert evaluation scores showed that students’ communication performance, when involved in peer assessments, significantly improved. |

| 13 | Martin and Chanda 2016 [36] (USA) | There was significant improvement (p = 0.000), in student’s self-reported confidence with their communication skills and knowledge following a mental health simulation experience using standardized patients. | A therapeutic communication mental health simulation give before students participating in their clinical experience should be integrated into undergraduate nursing education. |

| 14 | Taghizadeh et al. 2017 [46] (Iran) | The results showed that there was a significant difference between the mean quality of patients’ care prior to and following the intervention (p≤0.001). Also, there was a significant difference between the means for nursing student’s’ communication skills before and after the intervention (p≤0.001). Moreover, there was a significant correlation between mean scores of students and the quality of care and communication skills (p≤0.001). | The course was effective in improving communication skills in nursing students. |

| 15 | Shorey et al. 2018 [28] (China) | There was a statistically significant increase in the BLSS scores from pre-test to post-test (p = 0.012). Similarly, a statistically significant increase in the CSAS scores were seen from pre-test to post-test (p = 0.042). There was also a statistically significant increase in the C-NSSES scores from pre-test to post-test (p = 0.003). | Participants had enhanced satisfaction levels with blended learning pedagogy, better attitudes in learning communication skills, and improved communication self-efficacies at posttest. |

| 16 | Blake and Blake 2019 [39] (USA) | An improvement in student self-efficacy in therapeutic communication skills after the course simulation as indicated by the five questions were all significant with p < 0.01. | The lab simulation was helpful in improving students regarding their therapeutic communication skills. |

| 17 | Donovan and Mullen 2019 [26] (USA) | The pre/post results suggest the standardized simulated experience enhanced nursing student confidence p < 0.001. These results suggest that the student nurse confidence in therapeutic communication with a mental health patient had increased. | Simulation with SPs promoted an active learning environment that highlighted individualized confidence in therapeutic communication skills through a realistic application process. |

| 18 | Gaylle 2019 [33] (USA) | The overall change from pretest to posttest for therapeutic communication for both groups combined was statistically significant and practically important with a large effect size of 1.34 (Cohen d). On average, both groups showed statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05). The in-simulation group demonstrated a greater increase in therapeutic-communication techniques and a larger decrease in nontherapeutic communication than their peers in the post-simulation group. Differences in means between the in-simulation and the post-simulation groups for therapeutic communication (mean, 1.39 and 0.83) but there are not statistically differences significant between groups. | In simulation debriefing is an effective tool for teaching therapeutic communication to nursing students. |

| 19 | Ok et al. 2019 [37] (Turkey) | There are differences between the students who received and who did not receive SPS in terms of the scores obtained from the STAI-S (p = 0.01), STAI-T (p = 0.046), but there are not statistically differences in CSI (p = 0.09), except for the subscale cognitive of the CSI (p = 0.043). The comparison of the scores obtained by the intervention group prior to and after the SPS shows a statistically meaningful decrease in the anxiety levels (p = 0.001; p = 0.009) and a statistically meaningful increase in the communication skills of the intervention group after the simulation exercise (p = 0.001), except for the emotional subscale (p = 0.074). | Simulation with SPs may help nursing students gain experience and increase communication skills with patients. |

| Order Number | MAStARI Question | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st author, date (Country) | |||||||||||

| 1 | Baghcheghi et al. 2011 [41] (Iran) | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 2 | Kim et al. 2012 [34] (Korea) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 3 | Wittenberg-Lyles et al. 2012 [47] (USA) | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 4 | Jo and An 2013 [43] (Korea) | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 5 | Lau and Wang 2013 [44] (China) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 6 | Lau and Wang 2014 [45] (China) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 7 | Webster 2014 [38] (USA) | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 8 | Bloomfield et al. 2015 [32] (UK) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | 6 |

| 9 | Yoo and Park 2015 [42] (Korea) | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 10 | Lai 2016 [40] (Taiwan) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 7 |

| 11 | Martin and Chanda 2016 [36] (USA) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 12 | Taghizadeh et al. 2017 [46] (Iran) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 13 | Shorey et al. 2018 [28] (China) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| 14 | Blake and Blake 2019 [39] (USA) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | 5 |

| 15 | Donovan and Mullen 2019 [26] (USA) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 16 | Gaylle 2019 [33] (USA) | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| 17 | Ok et al. 2019 [37] (Turkey) | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Order Number | MAStARI Question | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st author, date (Country) | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | Becker et al. 2006 [31] (USA) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| 2 | Lin et al. 2013 [35] (Taiwan) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutiérrez-Puertas, L.; Márquez-Hernández, V.V.; Gutiérrez-Puertas, V.; Granados-Gámez, G.; Aguilera-Manrique, G. Educational Interventions for Nursing Students to Develop Communication Skills with Patients: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2241. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072241

Gutiérrez-Puertas L, Márquez-Hernández VV, Gutiérrez-Puertas V, Granados-Gámez G, Aguilera-Manrique G. Educational Interventions for Nursing Students to Develop Communication Skills with Patients: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(7):2241. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072241

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutiérrez-Puertas, Lorena, Verónica V. Márquez-Hernández, Vanesa Gutiérrez-Puertas, Genoveva Granados-Gámez, and Gabriel Aguilera-Manrique. 2020. "Educational Interventions for Nursing Students to Develop Communication Skills with Patients: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2241. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072241