How Servant Leadership Leads to Employees’ Customer-Oriented Behavior in the Service Industry? A Dual-Mechanism Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

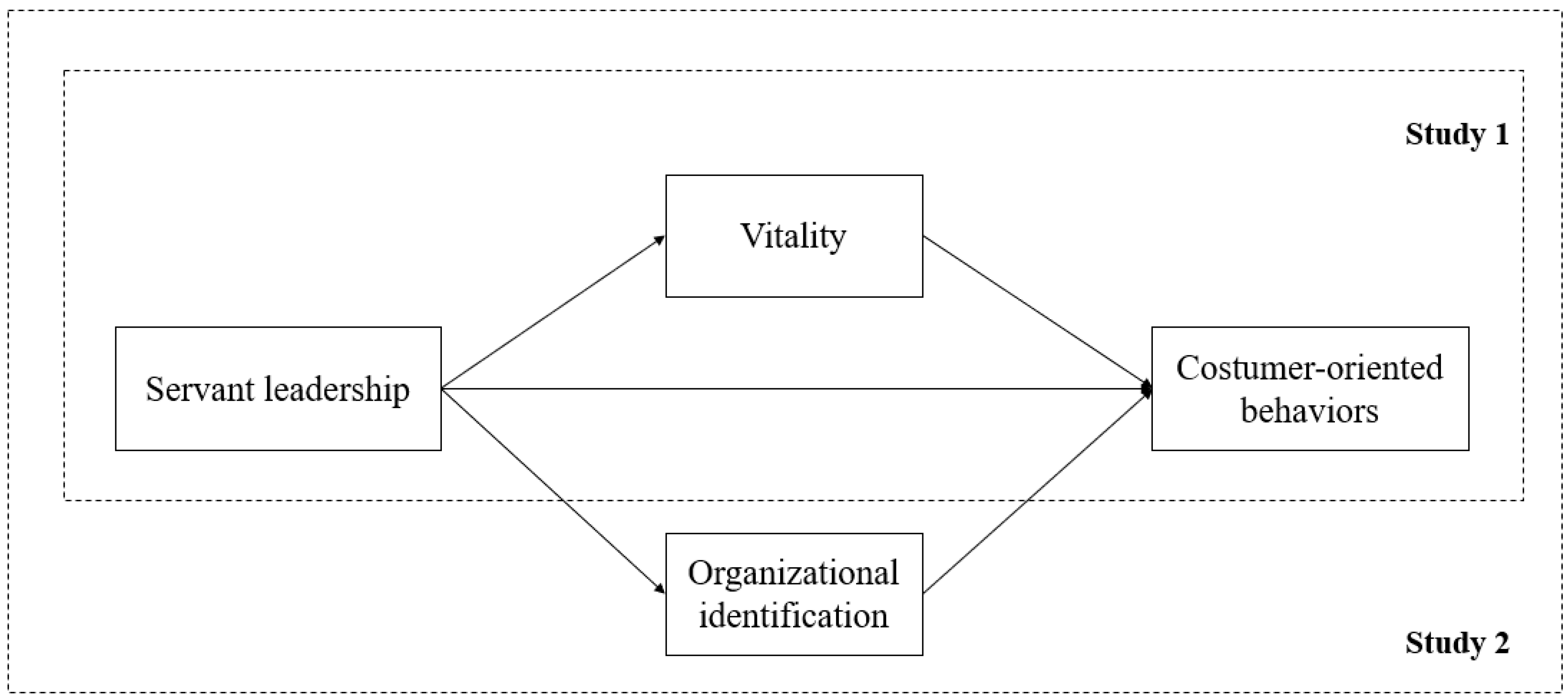

2. Research Background and Theoretical Discussion

3. Theory and Hypotheses

3.1. Servant Leadership and Employees’ Customer-Oriented Behavior

3.2. Vitality as a Mediator

3.3. Organizational Identification as a Mediator

4. Study 1

4.1. Sample and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.3. Results

4.4. Discussion

5. Study 2

5.1. Sample and Procedure

5.2. Measures

5.3. Results

5.4. Discussion

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Servant Leadership (Study 1 and 2) | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |

| 1. My manager can tell if something work-related is going wrong. | 0.77 | 0.83 |

| 2. My manager makes my career development a priority. | 0.85 | 0.80 |

| 3. I would seek help from my manager if I had a personal problem. | 0.88 | 0.77 |

| 4. My manager emphasizes the importance of giving back to the community. | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| 5. My manager puts my best interests ahead of his/her own. | 0.72 | 0.69 |

| 6. My manager gives me the freedom to handle difficult situations in the way that I feel is best. | 0.75 | 0.73 |

| 7. My manager would not compromise ethical principles in order to achieve success. | 0.65 | 0.60 |

| Organizational identification (Study 2) | ||

| 1. I feel strong ties with my organization. | 0.69 | |

| 2. I experience a strong sense of belonging to my organization. | 0.87 | |

| 3. I feel proud to work for my organization. | 0.84 | |

| 4. I am sufficiently acknowledged in my organization. | 0.83 | |

| 5. I am glad to be a member of my organization. | 0.83 | |

| Vitality (Study 1 and 2) | ||

| 1. I am most vital when I am at work. | 0.73 | 0.81 |

| 2. I am full of positive energy when I am at work. | 0.83 | 0.79 |

| 3. My organization makes me feel good. | 0.72 | 0.87 |

| 4. When I am at work, I feel a sense of physical strength. | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| 5. When I am at work, I feel mentally strong. | 0.87 | 0.72 |

| Customer-oriented Behavior (COB) (Study 1 and 2) | ||

| 1. I am always working to improve the service I give to customers. | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| 2. I have specific ideas about how to improve the service I give to customers. | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| 3. I often make suggestions about how to improve customer service in my department. | 0.71 | 0.76 |

| 4. I put a lot of effort into my job to try to satisfy customers. | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| 5. No matter how I feel, I always put myself out for every customer I serve. | 0.87 | 0.74 |

| 6. I often go out of my way to help customers. | 0.74 | 0.86 |

References

- Lanjananda, P.; Patterson, P.G. Determinants of customer-oriented behavior in a health care context. J. Serv. Manag. 2009, 20, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E. The changing role of employees in service theory and practice: An interdisciplinary view. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Lin, M.Z.; Wu, X.Y. The trickle-down effect of servant leadership on frontline employee service behaviors and performance: A multilevel study of Chinese hotels. Tourism Manag. 2016, 52, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Lyubovnikova, J.; Tian, A.W.; Knight, C. Servant leadership: A meta-analytic examination of incremental contribution, moderation, and mediation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 93, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, A.; Bavik, Y.L.; Tang, P.M. Servant leadership, employee job crafting, and citizenship behaviors: A cross-level investigation. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhan, Z.; Jia, M. Does servant leadership affect employees’ emotional labor? A social information-processing perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kwong Kwan, H.; Everett, A.M.; Jian, Z. Servant leadership, organizational identification, and work-to-family enrichment: The moderating role of work climate for sharing family concerns. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 747–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N.; Robin, M.; Sendjaya, S.; van Dierendonck, D.; Liden, R.C. Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Lee, A.; Tian, A.W.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhu, Y. Can coaching leadership encourage subordinates to speak up? Dual perspective of cognition-affection. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Carmeli, A. Alive and creating: The mediating role of vitality and aliveness in the relationship between psychological safety and creative workinvolvement. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, T.A.; Luthans, F.; Jeung, W. Thriving at work: Impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Muchiri, M.K.; Misati, E.; Wu, C.; Meiliani, M. Inspired to perform: A multilevel investigation of antecedents and consequences of thriving at work. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Loi, R.; Chow, C.W.C. What threatens retail employees’ thriving at work under leader-member exchange? The role of store spatial crowding and team negative affective tone. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 58, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Oke, A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A Socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lapointe, É.; Vandenberghe, C. Examination of the relationships between servant leadership, organizational commitment, and voice and antisocial behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzari, M.; Karatepe, O.M. Test of a mediation model of psychological capital among hotel salespeople. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2178–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1228–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenleaf, R.K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Paulist Press: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Parris, D.L.; Peachey, J.W. A systematic literature review of servant leadership theory in organizational contexts. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 113, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E.I.; Khapova, S.N.; Bossink, B.A. Servant leadership and innovative work behavior in Chinese high-tech firms: A moderated mediation model of meaningful work and job autonomy. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C. Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Dooley, L.M.; Xie, L. How servant leadership and self-efficacy interact to affect service quality in the hospitality industry: Apolynomial regression with response surface analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, C.J.; Lee, A.; Tian, A.W.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Does servant leadership’s people focus facilitate or constrain its positive impact on performance? An examination of servant leadership’s direct, indirect, and total effects on branch financial performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieder, R.E.; Wang, G.; Oh, I.-S. Linking job-relevant personality traits, transformational leadership, and job performance via perceived meaningfulness at work: A moderated mediation model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, E.; Stouten, J.; Hofmans, J. The cognitive-behavioral system of leadership: Cognitive antecedents of active and passive leadership behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenleaf, R.K.; Spers, L.C. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Roberts, K., Ed.; Paulist Press: Greenleaf, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 22, p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, J.E.; Lord, R.G.; Gardner, W.L.; Meuser, J.D.; Liden, R.C.; Hu, J. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: Current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.Y.; Moon, J.; Han, D.; Tikoo, S. Perceptions of justice and employee willingness to engage in customer-oriented behavior. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsted, K.F. Service behaviors that lead to satisfied customers. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartline, M.D.; Maxhim, G.J., III; McKee, D.O. Marketing corridors of influence in the dissemination of customer-oriented strategy to customer contact service employees. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, K.; Darby, N. A dual perspective of customer orientation: A modification, extension and application of the SOCO scale. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.W.; Randall, S. The indirect effects of organizational controls on salesperson performance and customer orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; White, S.S.; Paul, M.C. Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: Tests of a causal model. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G.; Newman, A.; Cooper, B.; Eva, N. Servant leadership and follower job performance: The mediating effect of public service motivation. Public Adm. 2016, 94, 1025–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Herrero, M.; van Dierendonck, D.; de Rivas, S.; Moreno-Jiménez, B. Servant leadership and goal attainment through meaningful life and vitality: A diary study. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 499–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shraga, O.; Shirom, A. The construct validity of vigor and its antecedents: A qualitative study. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L.; Steijn, B.; Nevicka, B.; Heerema, M. The effects of leadership and job autonomy on vitality: Survey and experimental evidence. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2018, 38, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Scheppingen, A.R.; De Vroome, E.; Ten Have, K.C.; Zwetsloot, G.I.; Wiezer, N.; van Mechelen, W. Vitality at work and its associations with lifestyle, self-determination, organizational culture, and with employees’ performance and sustainable employability. Work J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2015, 52, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Melamed, S.; Shirom, A.; Toker, S.; Berliner, S.; Shapira, I. Association of fear of terror with low-grade inflammation among apparently healthy employed adults. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbasi, A.; Porath, C.L.; Parker, A.; Spreitzer, G.; Cross, R. Destructive de-energizing relationships: How thriving buffers their effect on performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porath, C.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C.; Garnett, F.G. Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaiswal, N.K.; Dhar, R.L. The influence of servant leadership, trust in leader and thriving on employee creativity. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 2–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nix, G.A.; Ryan, R.M.; Manly, J.B.; Deci, E.L. Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 35, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, C.D. Antecedents and consequences of real-time affective reactions at work. Motiv. Emot. 2002, 26, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M. State or trait: Effects of positive mood on prosocial behaviors at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.; Brown, D.J. Leadership Processes Follower Self-Identity; Organization and Management Series; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sacre, L.; Masterson, J. Single Word Spelling Test; Nfer-Nelson, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Hogg, M.A. A social identity model of leadership effectiveness in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2003, 25, 243–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; van Knippenberg, D. Social identity and leadership processes in groups. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 35, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, R.H.; Blakely, G.L.; Niehoff, B.P. Does perceived organizational support mediate the relationship between procedural justice and organizational citizenship behavior? Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dierendonck, D.; Stam, D.; Boersma, P.; De Windt, N.; Alkema, J. Same difference? Exploring the differential mechanisms linking servant leadership and transformational leadership to follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Wong, N.; Abe, S.; Bergami, M. Cultural and situational contingencies and the theory of reasoned action: Application to fast food restaurant consumption. J. Consum. Psychol. 2000, 9, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickson, S.L. Organizational identity orientation: Forging a link between organizational identity and organizations’ relations with stakeholders. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 576–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.-P.; Herrbach, O. Social reporting as an organisational learning tool? A theoretical framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 65, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Transiation and content analysis of oral and written nateriais. Methodology 1980, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Peccei, R.; Rosenthal, P. Delivering customer-oriented behaviour through empowerment: An empirical test of HRM assumptions. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 831–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, R.B.; Dermen, D.; Harman, H.H. Manual for Kit of Factor-Referenced Cognitive Tests; Educational Testing Service: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1976; Volume 102. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, N.L.; Barrett, K.C.; Morgan, G.A. SPSS for Intermediate Statistics: Use and Interpretation; Psychology Press; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smidts, A.; Pruyn, A.T.H.; van Riel, C.B.M. The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multi-Level Theory, Research and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 349–381. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L.; Greene, D.; House, P. The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 13, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binyamin, G.; Brender-Ilan, Y. Leaders’s language and employee proactivity: Enhancing psychological meaningfulness and vitality. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, D.; Teo, S.T.; Tummers, L.; Newton, C.; Kruyen, P.M.; Vijverberg, D.M.; & Voesenek, T.J. Connecting HRM and change management: The importance of proactivity and vitality. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2015, 28, 627–640. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Value | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 157 | 54.5% |

| Female | 131 | 45.5% | |

| Education | High school/technical school | 8 | 2.8% |

| Associates degree | 83 | 28.8% | |

| Bachelors degree | 161 | 55.9% | |

| Masters degree and above | 36 | 12.5% | |

| Work tenure | <5 | 208 | 72.2% |

| 5–9 | 70 | 24.3% | |

| 10–14 | 5 | 1.7% | |

| >15 | 2 | 1.7% |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.46 | 0.50 | |||||||

| 2. Age | 30.14 | 5.66 | −0.13 * | ||||||

| 3. Education | 3.79 | 0.74 | 0.12 ** | 0.07 | |||||

| 4. Work tenure | 3.36 | 3.15 | 0.04 | 0.69 ** | −0.05 | ||||

| 5. Servant leadership | 3.61 | 0.66 | 0.03 | 0.20 ** | −0.07 | −0.11 | (0.87) | ||

| 6. Vitality | 3.85 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.35 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.44 ** | (0.86) | |

| 7. COB | 3.90 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.16 | −0.12 * | 0.06 | 0.26 ** | 0.47 ** | (0.88) |

| Variables | Variables Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Servant leadership | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.76 |

| Vitality | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.69 |

| COB | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.73 |

| Model 1 COB | Model 2 Vitality | Model 3 COB | Model 4 COB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.91 | −0.4 | −0.07 | −0.7 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.52 | 0.05 |

| Work tenure | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Servant leadership | 0.22 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.06 | |

| Vitality | 0.45 *** | 0.43 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| ΔR2 | 0.07 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.15 *** |

| F | 5.44 *** | 14.32 *** | 16.97 *** | 14.36 *** |

| ΔF | 20.09 | 68.22 | 76.33 *** | 53.80 |

| Variables | Value | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employees’ gender | Male | 107 | 58.8% |

| Female | 75 | 41.2% | |

| Employees’ education | High school/technical school | 87 | 47.8% |

| Associates degree | 65 | 35.7% | |

| Bachelors degree | 29 | 15.9% | |

| Masters degree and above | 1 | 0.5% | |

| Employees’ work tenure | <5 | 138 | 75.8% |

| 5–9 | 28 | 15.4% | |

| 10–14 | 8 | 4.4% | |

| >15 | 8 | 4.4% | |

| Leaders’ gender | Male | 20 | 64.5% |

| Female | 11 | 35.5% | |

| Leaders’ education | Associates degree and below | 8 | 25.8% |

| Bachelors degree | 18 | 58.1% | |

| Masters degree and above | 5 | 16.1% | |

| Leaders’ tenure in a management role | <5 | 23 | 74.2% |

| 5–9 | 7 | 22.7% | |

| >10 | 1 | 3.2% |

| Individual-Level Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.59 | 0.49 | |||||||

| 2. Age | 25.17 | 4.14 | 0.19 * | ||||||

| 3. Education | 1.65 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.53 ** | |||||

| 4. Work tenure | 3.31 | 3.83 | 0.17 * | 0.45 ** | 0.21 ** | ||||

| 5. Vitality | 3.98 | 0.66 | 0.24 ** | 0.23 ** | 0. 05 | 0.02 | (0.87) | ||

| 6. Organizational identification | 3.76 | 0.72 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.62 ** | (0.89) | |

| 7. COB | 4.01 | 0.65 | 0.16 * | 0.13 | 0. 06 | 0.10 | 0.80 ** | 0.68 ** | (0.86) |

| Team-level variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1. Leaders’ gender | 1.35 | 0.49 | |||||||

| 2. Leaders’ age | 30.71 | 3.84 | 0.08 | ||||||

| 3. Leaders’ education | 1.90 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 0.24 ** | |||||

| 4. Leaders’ work tenure | 4.16 | 2.66 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 0.43 * | ||||

| 5. Servant leadership | 3.95 | 0.63 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.16 | (0.86) |

| Variables | Variables Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Servant leadership | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.77 |

| Vitality | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.70 |

| Organizational identification | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.71 |

| COB | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.69 |

| Variables | Model 1 Vitality | Model 2 Organizational identification | Model 3 COB | Model 4 COB | Model 5 COB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | |||||

| Gender | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Age | 0.01 * | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 * |

| Work tenure | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 * | 0.02 * | 0.02 * |

| Vitality | 0.50 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.56 *** | ||

| Organizational identification | 0.28 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.19 *** | ||

| Level 2 | |||||

| Leaders’ gender | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Leaders’ age | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Leaders’ education | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.31 * | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| Leaders’ tenure | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Servant leadership | 0.29 * | 0.29 * | 0.53 *** | 0.21 ** | |

| Hypotheses | Results |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1. Servant leadership is positively related to employees’ customer-oriented behavior (Study 1 and Study 2). | Supported |

| Hypothesis 2. Servant leadership is positively related to employees’ vitality (Study 1 and Study 2). | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3. Vitality is positively related to employees’ customer-oriented behavior (Study 1 and Study 2). | Supported |

| Hypothesis 4. Vitality mediates the relationship between servant leadership and employees’ customer-oriented behavior (Study 1 and Study 2). | Supported |

| Hypothesis 5. Servant leadership is positively related to employees’ organizational identification (Study 2). | Supported |

| Hypothesis 6. Organizational identification is positively related to employees’ customer-oriented behavior (Study 2). | Supported |

| Hypothesis 7. Organizational identification mediates the relationship between servant leadership and employees’ customer-oriented behavior (Study 2). | Supported |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, M.; Cai, W.; Gao, X.; Fu, J. How Servant Leadership Leads to Employees’ Customer-Oriented Behavior in the Service Industry? A Dual-Mechanism Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2296. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072296

Yuan M, Cai W, Gao X, Fu J. How Servant Leadership Leads to Employees’ Customer-Oriented Behavior in the Service Industry? A Dual-Mechanism Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(7):2296. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072296

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Mengru, Wenjing Cai, Xiaopei Gao, and Jingtao Fu. 2020. "How Servant Leadership Leads to Employees’ Customer-Oriented Behavior in the Service Industry? A Dual-Mechanism Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2296. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072296