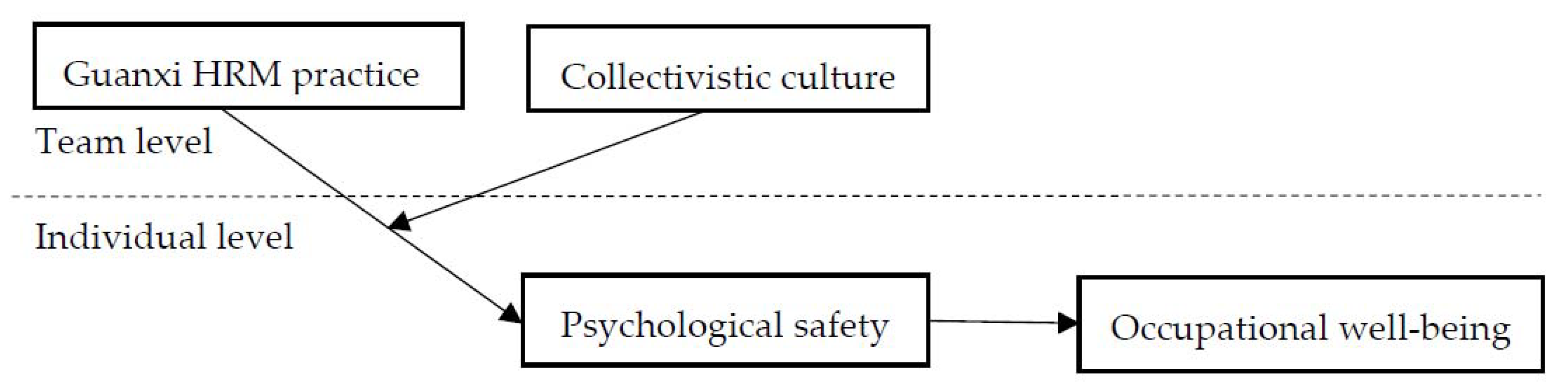

Guanxi HRM Practice and Employees’ Occupational Well-Being in China: A Multi-Level Psychological Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Guanxi HRM Practice, Psychological Safety, Collectivistic Culture, and Occupational Well-Being

2.2. Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory

2.3. Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Preliminary Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

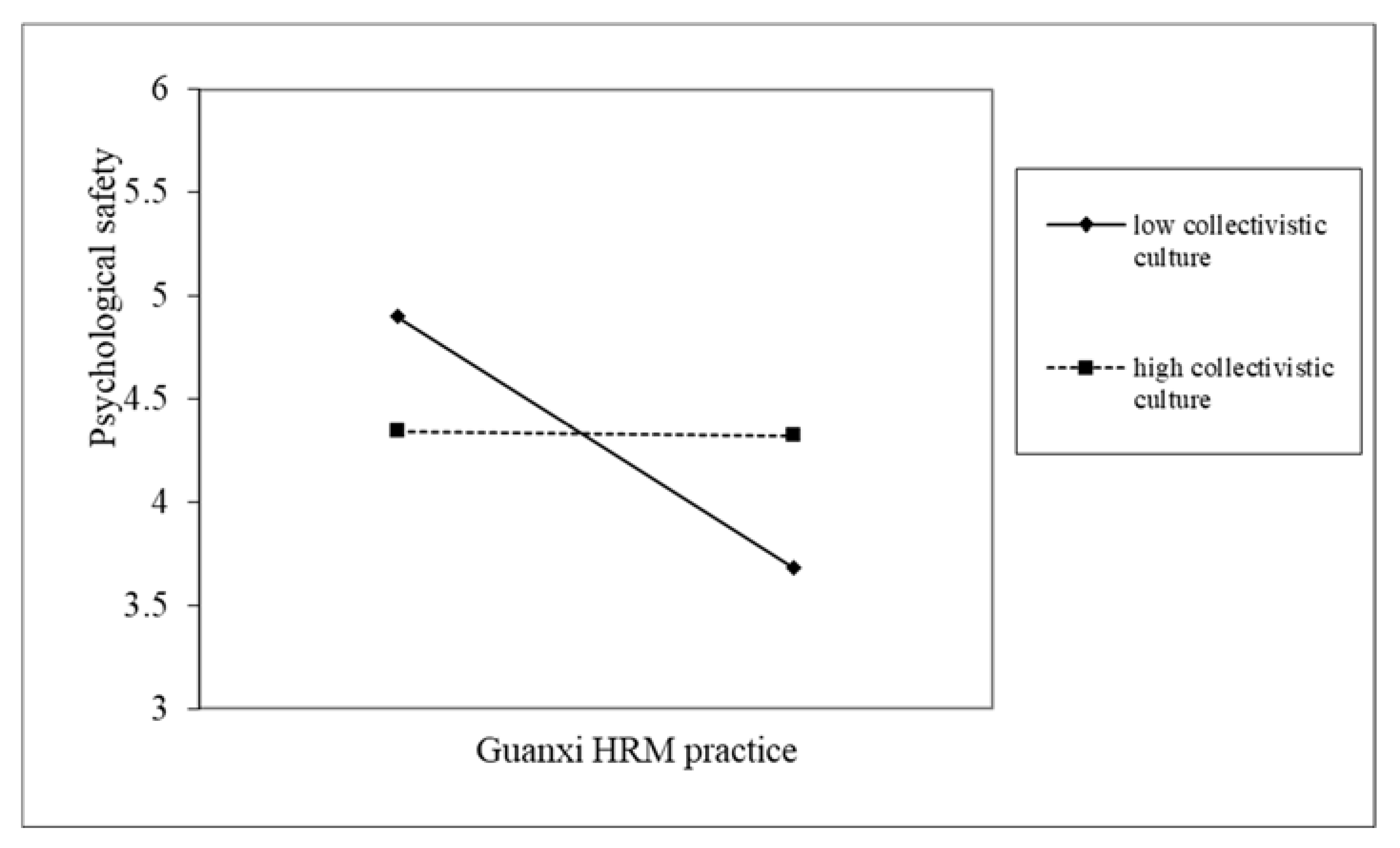

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mäkikangas, A.; Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T.; Schaufeli, W. The longitudinal development of employee well-being: A systematic review. Work. Stress 2016, 30, 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Cao, Y. High-Performance Work System, Work Well-Being, and Employee Creativity: Cross-Level Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Multiple Levels in Job Demands-Resources Theory: Implications for Employee Well-Being and Performance. In Handbook of Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; DEF Publisher: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, M.; Doherty, N. Performance management and well-being: A close look at the changing nature of the UK higher education workplace. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peccei, R.E.; Van De Voorde, K. The Application of the Multilevel Paradigm in Human Resource Management–Outcomes Research: Taking Stock and Going Forward. J. Manag. 2016, 45, 786–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peccei, R.; Van De Voorde, K. Human resource management–well-being–performance research revisited: Past, present, and future. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 539–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen, Y.; Xin, K. Guanxi Practices and Trust in Management: A Procedural Justice Perspective. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J. Interaction Rituals in Guanxi Practice and the Role of Instrumental Li. Asian Stud. Rev. 2017, 41, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen, X.-P. Negative externalities of close guanxi within organizations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2008, 26, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.; Wong, C.-S.; Wang, D.; Wang, L. Effect of supervisor–subordinate guanxi on supervisory decisions in China: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Huang, X.; Tang, D.; Yang, J.; Wu, L. How guanxi HRM practice relates to emotional exhaustion and job performance: The moderating role of individual pay for performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, L.; Wu, T.-Y.; Huang, X. When is pay for performance related to employee creativity in the Chinese context? The role of guanxi HRM practice, trust in management, and intrinsic motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 698–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-C.; Chaturvedi, S. The Role of Procedural Justice and Power Distance in the Relationship between High Performance Work Systems and Employee Attitudes: A Multilevel Perspective. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1228–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, L.; Bochner, S.; Schneider, S. Person-Organisation Fit across Cultures: An Empirical Investigation of Individualism and Collectivism. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Guanxi: Principles, philosophies, and implications. Hum. Syst. Manag. 1997, 16, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Farh, J.-L.L. Where Guanxi Matters: Relational Demography and Guanxi in the Chinese Context. Work Occup. 1997, 24, 56–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Frenkel, S.J. Explaining supervisor–subordinate guanxi and subordinate performance through a conservation of resources lens. Hum. Relat. 2018, 72, 1752–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalet, J. Guanxi as Social Exchange: Emotions, Power and Corruption. Sociology 2017, 52, 934–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, B.; Gold, T.; Guthrie, D.; Wank, D. Social Connections in China: Institutions, Culture, and the Changing Nature of Guanxi. Thomas Gold, Doug Guthrie, David Wank. China J. 2005, 53, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-P.; Chen, C.C. On the Intricacies of the Chinese Guanxi: A Process Model of Guanxi Development. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2004, 21, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. Guanxi human resource management practices as a double-edged sword: The moderating role of political skill. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2014, 52, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.Q.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wu, L.Z. Political Skill, Supervisor–Subordinate Guanxi and Career Prospects in Chinese Firms. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen, X.-P.; Huang, S. Chinese Guanxi: An Integrative Review and New Directions for Future Research. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2013, 9, 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, F.; Qian, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Chau, R.; Wang, T. Bridging the Gap: How Supervisors’ Perceptions of Guanxi HRM Practices Influence Subordinates’ Work Engagement. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 67, 589–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; O’Leary, P.F. Impact of Guanxi on Managerial Satisfaction and Commitment in China. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 23, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, W.G. Personal and Organizational Change through Group Methods: The Laboratory Approach; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, M.A.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. Psychological Safety in Ghana: Empirical Analyses of Antecedents and Consequences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirak, R.; Peng, A.C.; Carmeli, A.; Schaubroeck, J. Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, K.C.; Bozionelos, N. Team Exploratory and Exploitative Learning: Psychological Safety, Task Conflict, and Team Performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2011, 36, 385–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Erdogan, B.; Jiang, K.; Bauer, T.N.; Liu, S. Leader humility and team creativity: The role of team information sharing, psychological safety, and power distance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, M.L.; Tupper, C. Supervisor Prosocial Motivation, Employee Thriving, and Helping Behavior: A Trickle-Down Model of Psychological Safety. Group Organ. Manag. 2016, 43, 561–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, H.H.; Avolio, B.J. Team Psychological Safety and Conflict Trajectories’ Effect on Individual’s Team Identification and Satisfaction. Group Organ. Manag. 2018, 44, 843–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, M.L.; Fainshmidt, S.; Klinger, R.L.; Pezeshkan, A.; Vracheva, V. Psychological Safety: A Meta-Analytic Review and Extension. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 70, 113–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, A.; Donohue, R.; Eva, N. Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. The many dimensions of culture. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.M.; Mitchell, M.S.; Uhl-Bien, M. The New Conduct of Business: How Lmx Can Help Capitalize on Cultural Diversity. In Dealing with Diversity; Graen, G.B., Ed.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2003; pp. 183–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, P.; Newman, A. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 25, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. In The Science of Well-Being; Diener, E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 11–58. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P.B. Well-Being and the Workplace. In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, Russell Sage Foundation, New York; Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Xie, B.; Chung, B. Bridging the Gap between Affective Well-Being and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Work Engagement and Collectivist Orientation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Känsälä, M.; Saari, E.; Isaksson, K. Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work. Stress 2017, 31, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, T.A.; Huang, C.-C. The many benefits of employee well-being in organizational research. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1188–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Tu, Y.; Lu, X. Ethical Leadership and Subordinates’ Occupational Well-Being: A Multi-level Examination in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 116, 823–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, S.; Raja, U.; Haq, I.U.; Bilal, W. Job demand and employee well-being. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 1150–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.A.; Prottas, D.J. Relationships among organizational family support, job autonomy, perceived control, and employee well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Smith, R.M.; Palmer, N.F. Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ashleigh, M.; Higgs, M.; Dulewicz, V. A new propensity to trust scale and its relationship with individual well-being: Implications for HRM policies and practices. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2012, 22, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijden, B.I.; Mahoney, C.; Xu, Y. Impact of Job Demands and Resources on Nurses’ Burnout and Occupational Turnover Intention Towards an Age-Moderated Mediation Model for the Nursing Profession. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunfee, T.W.; Warren, D.E. Is Guanxi Ethical? A Normative Analysis of Doing Business in China. J. Bus. Ethic 2001, 32, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard-Oettel, C.; De Cuyper, N.; Schreurs, B.; De Witte, H. Linking job insecurity to well-being and organizational attitudes in Belgian workers: The role of security expectations and fairness. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1866–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, W.R. Guanxi Networks in China. Chin. Bus. Rev. 2004, 31, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. Filial Piety, Guanxi, Loyalty, and Money. In Trust and Distrust: Sociocultural Perspectives; Ivana Markova, A.G., Ed.; Information Age Pbulishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2008; pp. 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R.; Boer, D. What is more important for national well-being: Money or autonomy? A meta-analysis of well-being, burnout, and anxiety across 63 societies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Lei, Z. Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Freedy, J. Conservation of Resources: A General Stress Theory Applied to Burnout. In Professional Burnout; Informa UK Limited: London, UK, 2017; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, P.; Farndale, E. High-performance work systems and creativity implementation: The role of psychological capital and psychological safety. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Chadee, D. Influence of work pressure on proactive skill development in China: The role of career networking behavior and Guanxi HRM. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F.; Bakker, A.B. Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edmondson, A.C. The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.; Foo, S.C.; Groth, M.; Goodwin, R.E. Free to be you and me: A climate of authenticity alleviates burnout from emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, K.C.; Fehr, R.; Keng-Highberger, F.T.; Klotz, A.C.; Reynolds, S.J. Out of Control: A Self-Control Perspective on the Link between Surface Acting and Abusive Supervision. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, M.; Choi, J.N.; Lee, S.-H. Does Team Culture Matter? Roles of Team Culture and Collective Regulatory Focus in Team Task and Creative Performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 41, 232–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.S.; Drolet, A. Choice and self-expression: A cultural analysis of variety-seeking. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.S.; Morris, M.W.; Talhelm, T.; Yang, Q. Ingroup vigilance in collectivistic cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 14538–14546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branzei, O.; Vertinsky, I.; Camp, R.D. Culture-contingent signs of trust in emergent relationships. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 104, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wated, G.; Sanchez, J.I. Managerial Tolerance of Nepotism: The Effects of Individualism–Collectivism in a Latin American Context. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 130, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, B.; Liden, R.C. Collectivism as a moderator of responses to organizational justice: Implications for leader-member exchange and ingratiation. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J. Multivariate Multilevel Regression Model. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brunetto, Y.; Farr-Wharton, R.; Shacklock, K. Using the Harvard HRM model to conceptualise the impact of changes to supervision upon HRM outcomes for different types of Australian public sector employees. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wagner, J.A.; Moch, M.K. Individualism-Collectivism: Concept and Measure. Group Organ. Stud. 1986, 11, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Age and Occupational Well-Being. Psychol. Aging 1992, 7, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doverspike, D.; Blumental, A. Gender Issues in the Measurement of Physical and Psychological Safety. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2001, 22, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Structural Equation Models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toothaker, L.E.; Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1994, 45, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, W.W.; Liu, G. Overcoming the liability of smallness by recruiting through networks in China: A guanxi-based social capital perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 28, 1499–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ho, H.; Kuvaas, B. Human resource management systems, employee well-being, and firm performance from the mutual gains and critical perspectives: The well-being paradox. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.; Truss, C. The link between perceived HRM practices, performance and well-being: The moderating effect of trust in the employer. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2012, 22, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabris, G.T.; Ihrke, D.M. Does Performance Appraisal Contribute to Heightened Levels of Employee Burnout? The Results of One Study. Public Pers. Manag. 2001, 30, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veld, M.; Alfes, K. HRM, climate and employee well-being: Comparing an optimistic and critical perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 2299–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, F.; Nolan, J.; Rowley, C. Organizational justice in Chinese banks: Understanding the variable influence of guanxi on perceptions of fairness in performance appraisal. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-E.; Yu, S.; Chen, Y.; He, W. Supervision Incivility and Employee Psychological Safety in the Workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.W.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, S. Does gender diversity help teams constructively manage status conflict? An evolutionary perspective of status conflict, team psychological safety, and team creativity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2018, 144, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S. Conservation of resources theory and the ’strength’ model of self-control: Conceptual overlap and commonalities. Stress Health 2015, 31, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T. Longitudinal Research in Occupational Health Psychology; Informa UK Limited: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, W.; Wang, A. Downsides of Guanxi Practices in Chinese Organizations. In 68th Annual Academy of Management Meeting; Academy of Management: Anaheim, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Winkel, D.E.; Selvarajan, T.T. Managing diversity at work: Does psychological safety hold the key to racial differences in employee performance? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual level (n = 297) | |||||

| 1. Psychological safety | 3.19 | 0.47 | |||

| 2. Occupational well-being | 3.49 | 0.64 | 0.47 ** | ||

| Team level (n = 42) | |||||

| 3. Guanxi HRM practice | 3.23 | 0.42 | −0.29 ** | −0.28 ** | |

| 4.Collectivistic culture | 3.94 | 0.40 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Variables | Occupational Well-Being | Psychological Safety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

| Independent Variable (level 2) | ||||

| Guanxi HRM practice | −0.427 ***(0.089) | −0.266 *(0.127) | −0.323 ***(0.060) | −0.305 ***(0.051) |

| Mediator (level 1) | ||||

| Psychological safety | −0.318 ***(0.062) | |||

| Moderator (level 2) | ||||

| Collectivistic culture | 0.015 (0.052) | |||

| Interaction (level 2) | ||||

| Collectivistic culture * guanxi HRM practice | 0.300 *(0.147) | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Xie, B.; Tang, B. Guanxi HRM Practice and Employees’ Occupational Well-Being in China: A Multi-Level Psychological Process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2403. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072403

Xu J, Xie B, Tang B. Guanxi HRM Practice and Employees’ Occupational Well-Being in China: A Multi-Level Psychological Process. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(7):2403. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072403

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jia, Baoguo Xie, and Bin Tang. 2020. "Guanxi HRM Practice and Employees’ Occupational Well-Being in China: A Multi-Level Psychological Process" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2403. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072403