Investigation on Life Satisfaction of Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers in China: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

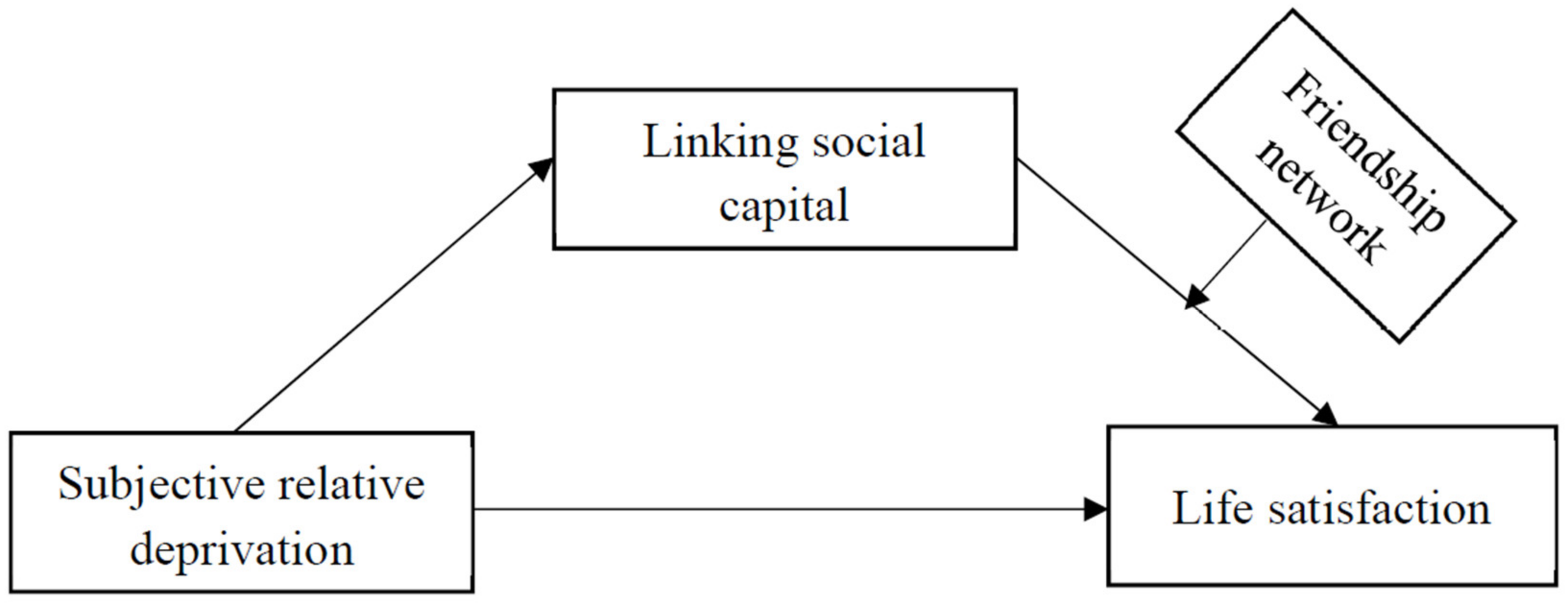

2. Literature Review

2.1. Subjective Relative Deprivation and Mental Health

2.2. Linking Social Capital and Mental Health

2.3. Friendship as a Moderator

2.4. Subjective Relative Deprivation and Linking Social Capital

2.5. Internal Migrants’ Life Satisfaction

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Analysis

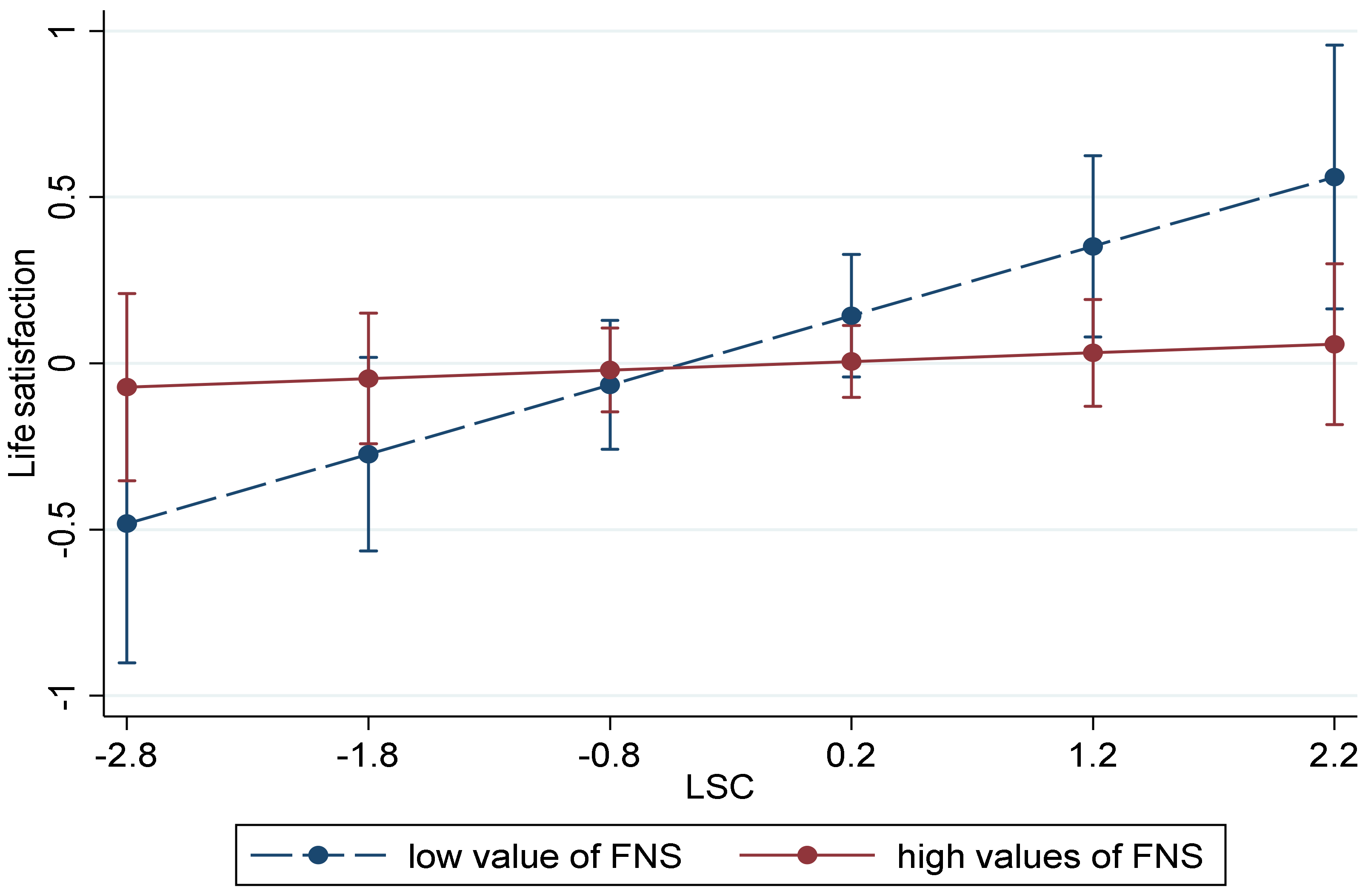

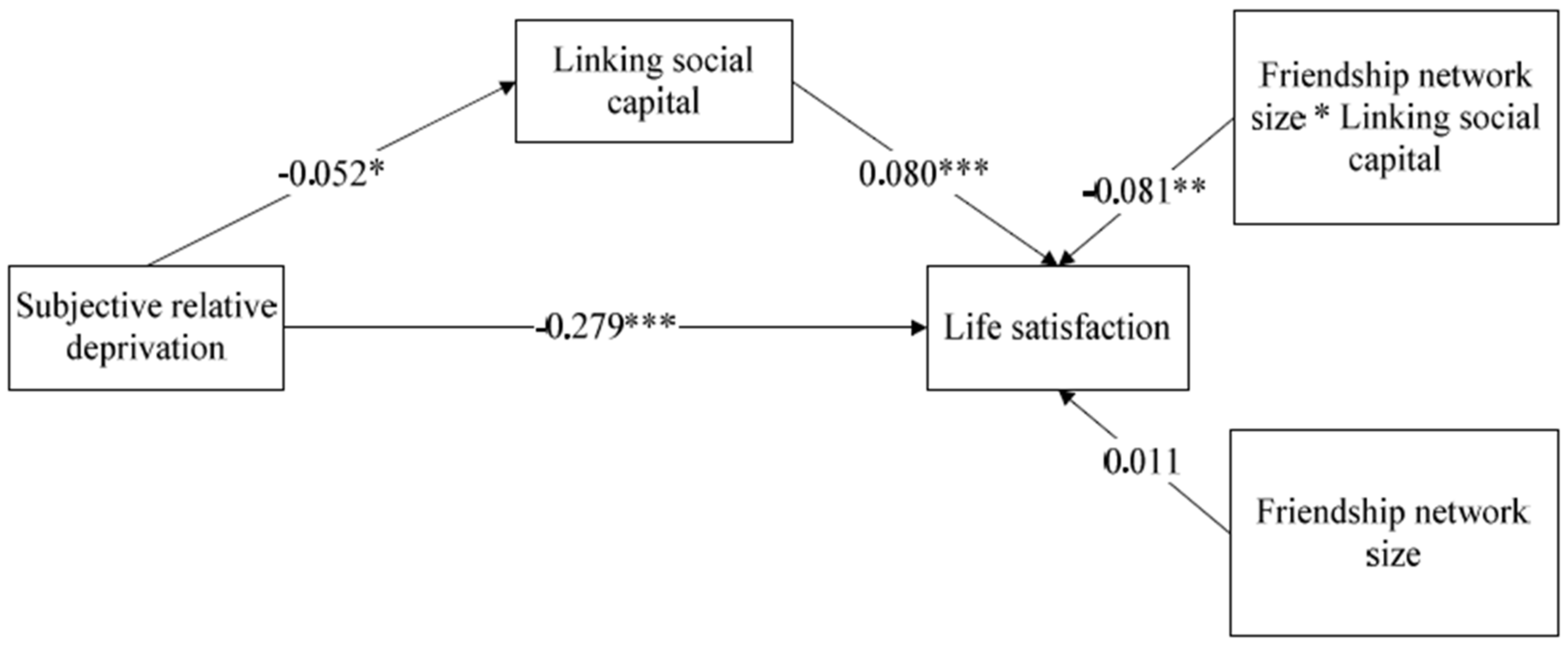

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, M.; Yang, T. Geography, trade, and internal migration in China. J. Urban Econ. 2020, 115, 103181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. The Monitoring Survey Report of Migrant Peasant Workers in China in 2018; State Statistic Bureau: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Millán-Franco, M.; Gómez-Jacinto, L.; Hombrados-Mendieta, I.; García-Martín, M.A.; García-Cid, A. Influence of time of residence on the sense of community and satisfaction with life in immigrants in Spain: The moderating effects of sociodemographic characteristics. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arévalo, S.P.; Tucker, K.L.; Falcón, L.M. Beyond cultural factors to understand immigrant mental health: Neighborhood ethnic density and the moderating role of pre-migration and post-migration factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 138, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bonnefond, C.; Mabrouk, F. Subjective well-being in China: Direct and indirect effects of rural-to-urban migrant status. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2019, 77, 442–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xue, S. Social networks and mental health outcomes: Chinese rural-urban migrant experience. J. Popul. Econ. 2020, 33, 155–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solinger, D.J. Contesting Citizenship in Urban China: Peasant Migrants, the State, and the Logic of the Market; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, F. The Hukou System Reform and Unification of Rural-Urban Social Welfare. Econ. Perspect. 2010, 12, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z. China’s great migration and the prospects of a more integrated society. Rev. Sociol. 2016, 42, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, J. The two-tier labor market in urban China: Occupational segregation and wage differentials between urban residents and rural migrants in Shanghai. J. Comp. Econ. 2001, 29, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Piotrowski, M. Migration and Health Selectivity in the Context of Internal Migration in China, 1997–2009. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2012, 31, 497–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Song, L. The Rural-Urban Divide Economic Disparities and Interactions in China; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.; Gunatilaka, R. Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural-urban migrants in China. World Dev. 2010, 38, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, B.; Li, X.; Stanton, B.; Fang, X. The influence of social stigma and discriminatory experience on psychological distress and quality of life among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.L. Time and transnationalism: A longitudinal study of immigration, endurance and settlement in Canada. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2011, 37, 1119–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Schönfeld, P.; Kochetkov, Y.; Margraf, J. What does migration mean to us? USA and Russia: Relationship between migration, resilience, social support, happiness, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety and stress. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Zhao, G. Identity and trust in government: A comparison of locals and migrants in urban China. Cities 2018, 83, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Carleton, R.N. Subjective relative deprivation is associated with poorer physical and mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, F. Economic disadvantages and migrants’ subjective well-being in China: The mediating effect of relative deprivation and neighbourhood deprivation. Popul. Space Place 2018, 25, e2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L. Migration, relative deprivation, and psychological well-being in China. Am. Behav. Sci. 2016, 60, 750–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Rana, A.K.M.; Kabir, Z.N. Social capital and quality of life in old age. J. Aging Health 2006, 18, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.; Goss, K.A. Introduction. In Democracies in Flux. The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society; Putnam, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Szreter, S.; Woolcock, M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 33, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J. Social capital and health in China: Evidence from the Chinese general social survey 2010. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofors, J.; Sundquist, K. Low-linking social capital as a predictor of mental disorders: A cohort study of 4.5 million Swedes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, P. Is linking social capital more beneficial to the health promotion of the poor? Evidence from China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 147, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, N.A.; Maltby, E.; Rocha, R.R. How the link between social capital and migratory duration helps us understand immigrant-native inequality? Soc. Sci. Q. 2019, 100, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Sun, R.C.F.; Yuen, M. Acculturation, economic stress, social relationships and school satisfaction among migrant children in urban China. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 17, 507–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Huebner, E.S. Peer victimization and prosocial experiences and emotional well-being of middle school students. Psychol. Sch. 2007, 44, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, M.; Ludwigs, K.; Veenhoven, R. Why are Locals Happier than Internal Migrants? The Role of Daily Life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 125, 481–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settle, J.E.; Bond, R.; Levitt, J. The social origins of adult political behavior. Am. Politics Res. 2011, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, W.; Rose, R. Trust, distrust and skepticism: Popular evaluations of civil and political institutions in post-communist societies. J. Politics 1997, 59, 418–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Glasure, Y.U. Political cynicism in South Korea: Economics or values? Asian Aff. 2002, 29, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinjoan, M.; Rico, G. How perceptions of inequality between countries diminish trust in the European Union: Experimental and observational evidence. Political Psychol. 2018, 39, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E.M. The Moral Foundations of Trust; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Relative Deprivation and Political Trust among Youth in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Macao J. 2019, 3, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, O.; Jakubek, M. Integration as a catalyst for assimilation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2013, 28, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nesterko, Y.; Braehler, E.; Grande, G.; Glaesmer, H. Life satisfaction and health-related quality of life in immigrants and native-born Germans: The role of immigration-related factors. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. Life satisfaction, concept of. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3599–3601. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zou, J.; Luo, J. Mental health symptoms among rural adolescents with different parental migration experiences: A cross-sectional study in China. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 279, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Davis, D.S.; Wu, K.; Dai, H. Life satisfaction in urbanizing China: The effect of city size and pathways to urban residency. Cities 2015, 49, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chu, R.; Hail, H.C. Winding road toward the Chinese dream: The U-shaped relationship between income and life satisfaction among Chinese migrant workers. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Gottlieb, B.; Underwood, L. Social relationships and health. In Social Support Measurement and Intervention; Cohen, S., Underwood, L., Gottlieb, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, E. Reference Groups and Social Evaluations. In Social Psychology: Sociological Perspectives; Rosenberg, M., Turner, R.H., Eds.; Basic Books, Inc: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 66–93. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.H. Political issues and trust in government, 1964–1970. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1974, 68, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, X. Social policy and political trust: Evidence from the New Rural Pension Scheme in China. China Q. 2018, 235, 644–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, W. Determinants of public trust in government: Empirical evidence from urban China. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 83, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folland, S.; Nauenberg, E. Elgar Companion to Social Capital and Health; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson, P. Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher and the Politics of Retrenchment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Y.L.; Solomon, P.L. Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities in supportive independent housing: A conceptual model and methodological considerations. Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, J.N.; Susser, E. Social integration in global mental health: What is it and how can it be measured? Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2013, 22, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, J.F.; Berenson, K.; Cohen, P.; Garcia, J. The role of parent and peer support in predicting adolescent depression: A longitudinal community study. J. Res. Adolesc. 2005, 15, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean ± SD (Range) N (%) | Number of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.54 ± 10.37 (16–76) | 2435 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1394 (57.08%) | 2442 |

| Female | 1048 (42.92%) | |

| Marital status | ||

| With a spouse | 1793 (73.48%) | 2440 |

| Single (unmarried/divorced/widowed) | 647 (26.52%) | |

| Education | ||

| Primary education or below | 277 (11.35%) | 2441 |

| Junior high education | 1001 (41.01%) | |

| Senior high or technical secondary education | 781 (32.00%) | |

| tertiary education and above | 382 (15.65%) | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | 3866.053 ± 1861.695(1500–9000) | 2359 |

| Occupation | ||

| Employed | 1706 (77.97%) | 2188 |

| Self-employed | 482 (22.03%) | |

| Duration of stay | 8.40 ± 7.46(1–63) | 2436 |

| Immigration distance | ||

| Inter-provincial migration | 911 (37.31%) | 2442 |

| Inner-provincial migration | 1531 (62.69%) | |

| Immigratory place | ||

| Changsha | 1245 (50.98%) | 2442 |

| Xiamen | 1197 (49.02%) |

| Variable | Mean ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Subjective relative deprivation | 4.36 ± 0.89 | 1 | −0.05 * | −0.07 * | −0.29 * |

| 2. Linking social capital | 1.59 ± 0.57 | 1 | 0.05 * | 0.09 * | |

| 3. Friendship network size | 34.95 ± 31.38 | 1 | 0.02 | ||

| 4. Life satisfaction | 3.59 ± 0.81 | 1 |

| Variable | Linking Social Capital | Life Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | ||

| Subjective relative deprivation | −0.052 * | −0.284 *** | −0.280 *** | −0.004 *[−0.008, −0.00005] |

| Linking social capital | — | 0.079 *** | 0.079 *** | — |

| Age | 0.171 *** | 0.084 ** | 0.071 ** | 0.013 ** |

| Gender | 0.010 | −0.049 * | −0.050 * | 0.001 |

| Marital status | −0.015 | −0.004 | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| Education | 0.035 | 0.051 * | 0.048 * | 0.003 |

| Income | −0.019 | 0.010 | 0.011 | −0.002 |

| Occupation | −0.004 | 0.018 | 0.017 | −0.0003 |

| Duration of stay | −0.028 | 0.044 | 0.046 * | −0.002 |

| Origin areas | −0.002 | −0.008 | −0.008 | −0.0001 |

| Immigratory place | 0.222 *** | −0.0132 | −0.031 | 0.017 ** |

| Variable | Linking Social Capital | Life Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | ||

| Subjective relative deprivation | −0.052 * | −0.283 *** | −0.279 *** | −0.004 * [−0.008, −0.0001] |

| Linking social capital | — | 0.080 *** | 0.080 *** | — |

| Friendship network size | — | 0.011 | 0.011 | — |

| Linking social capital × Friendship network size | — | −0.081 ** | −0.081 ** | — |

| Age | 0.171 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.070 ** | 0.014 ** |

| Gender | 0.010 | −0.052 * | −0.053 ** | 0.001 |

| Marital status | −0.015 | −0.003 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| Education | 0.035 | 0.051 * | 0.048 * | 0.003 |

| Income | −0.019 | 0.007 | 0.009 | −0.002 |

| Occupation | −0.004 | 0.019 | 0.019 | −0.0003 |

| Duration of stay | −0.028 | 0.041 | 0.044 * | −0.002 |

| Origin areas | −0.002 | −0.006 | −0.006 | −0.0001 |

| Immigratory place | 0.222 *** | −0.0132 | −0.031 | 0.018 *** |

| Variable | Coef. | BootSE | z | p > |z| | BC [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Friendship network size | −0.008 | 0.004 | −20.08 | 0.037 | −0.0191 | −0.0018 |

| Average Friendship network size | −0.004 | 0.002 | −10.94 | 0.052 | −0.0109 | −0.0010 |

| High Friendship network size | −0.0001 | 0.002 | −0.07 | 0.946 | −0.0042 | 0.0031 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Q.; Pan, H. Investigation on Life Satisfaction of Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2454. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072454

Liu Q, Pan H. Investigation on Life Satisfaction of Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(7):2454. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072454

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Qian, and Haimin Pan. 2020. "Investigation on Life Satisfaction of Rural-to-Urban Migrant Workers in China: A Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 7: 2454. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17072454