Examining the Effects of Overtime Work on Subjective Social Status and Social Inclusion in the Chinese Context

Abstract

:“They won’t let us go unless we have everything finished. So we have to work overtime···. If we didn’t finish the work even in 10 h, we stay until 2 a.m. We have to finish the work.”Statement of a food packer worker [1]

1. Introduction

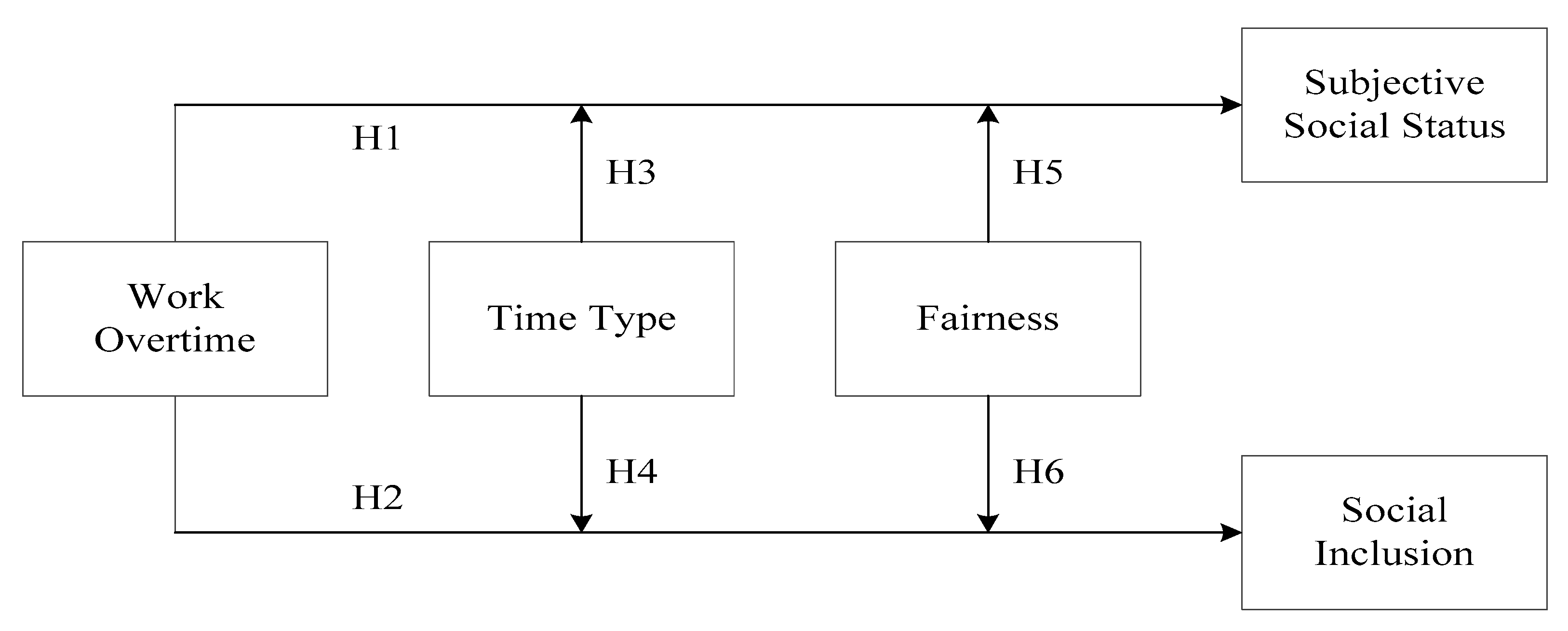

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Overtime Work and Subjective Social Status

2.3. Overtime and Social Inclusion

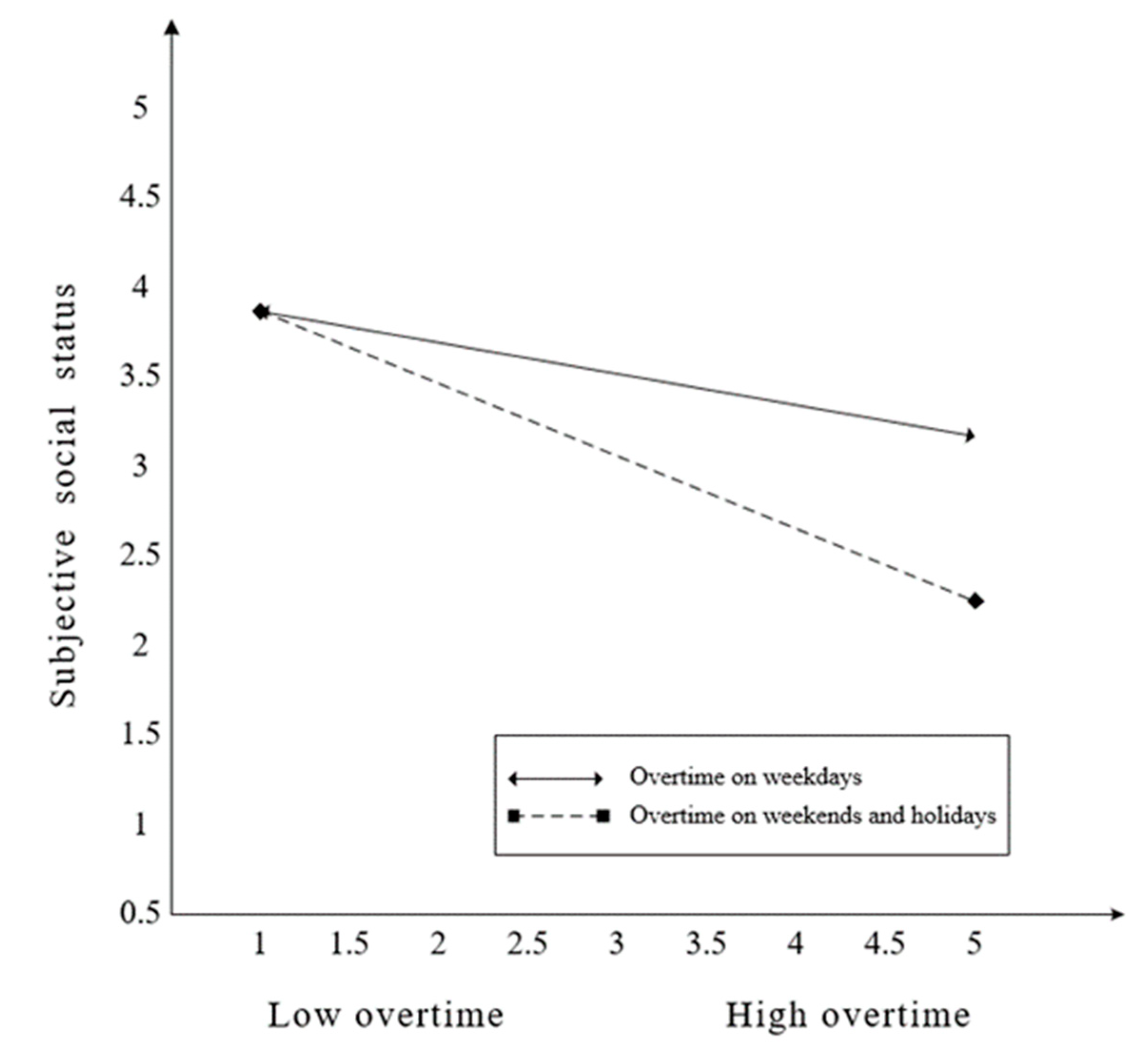

2.4. Time Type of Overtime as a Moderator

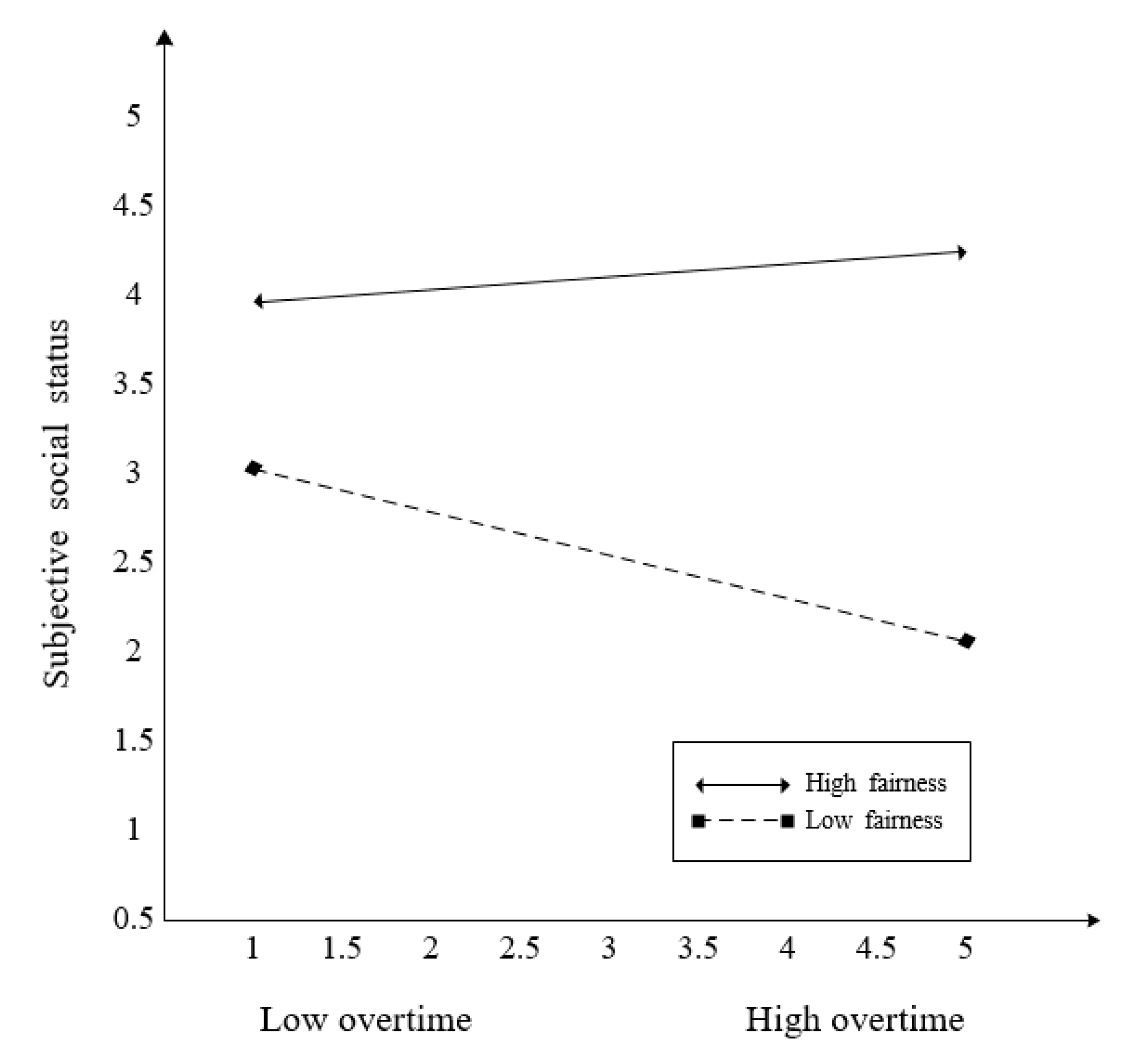

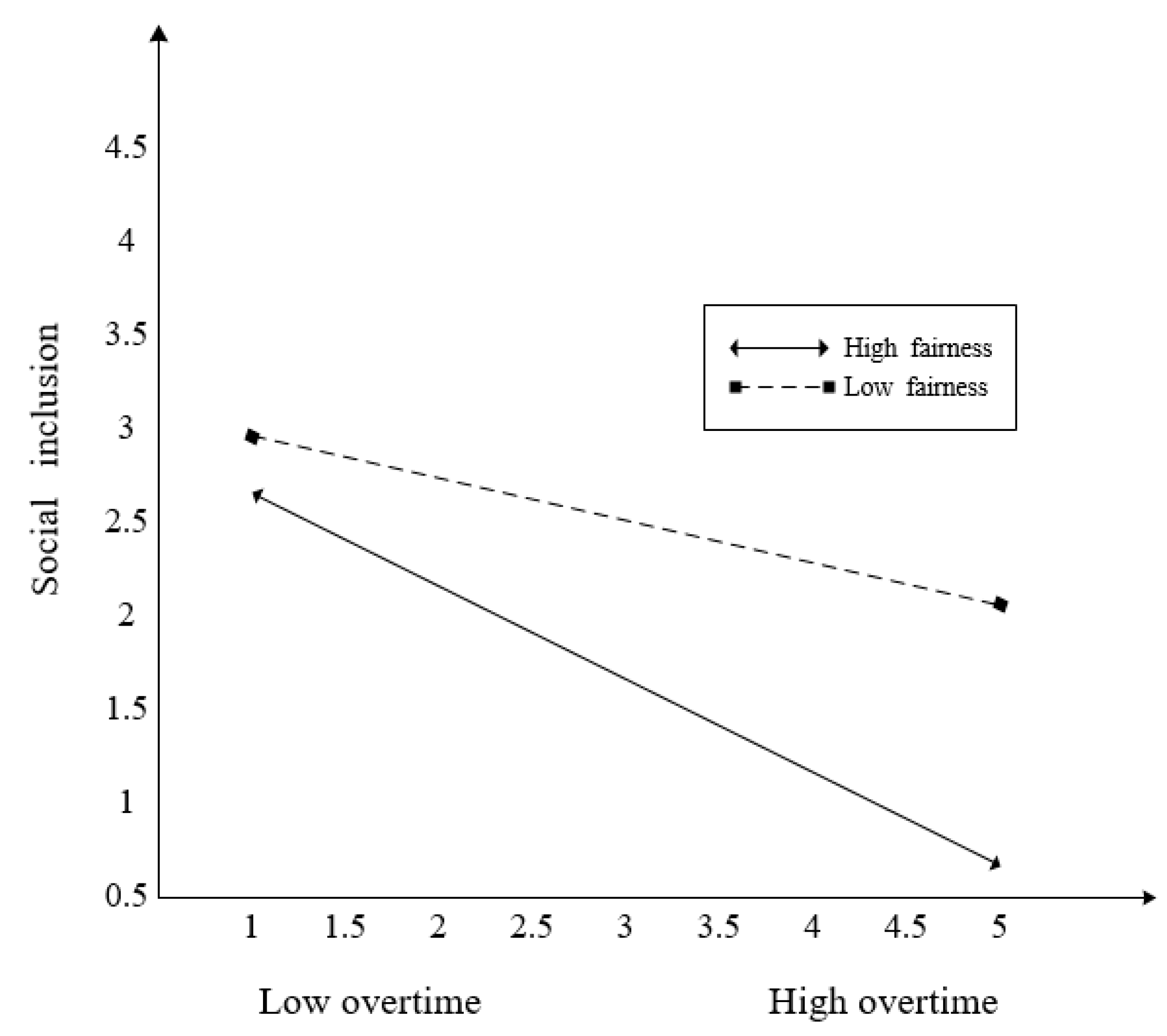

2.5. Perceptions of Effort-Reward Fairness as a Moderator

3. Method

3.1. Data Source and Description

3.2. Measures

- Overtime work. Overtime work was measured using the overtime working hours in the past month.

- Overtime type. We divided the type of overtime into two types: overtime work on weekdays and overtime work on weekends and holidays.

- Fairness. The questionnaire measures the effort-reward fairness by comparing the current living standard of the respondents with their work efforts. A five-point scale was adopted to measure the effort-reward fairness, ranging from 1 (totally unfair) to 5 (totally fair). The higher the score, the greater the effort-reward fairness.

- Subjective social status. In the questionnaire, the subjective social status was directly measured by the social status rating of the respondents. Social status was graded by 10 points. From 1 (the lowest level) to 10 (the highest level), the higher the score, the higher the subjective social status.

- Social inclusion. Social inclusion was measured by the willingness to settle locally in the future. A five-point scale was adopted, ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely). The higher the score, the more willing to settle in the future.

- Control variables. Participants’ gender, age (in years), marriage, annual income, residence type, and overtime location were treated as control variables in the study. A description of these variables is shown in Table 1.

3.3. Data Analysis Method and Model Estimation

4. Results

4.1. Testing Hypotheses 1 and 2

4.2. Testing Hypotheses 3, 4, 5, and 6

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levin, R.; Ginsburg, R. Sweatshops in Chicago: A Survey of Working Conditions in Low-Income and Immigrant Communities; Center for Impact Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Parent-Thirion, A.; Biletta, I.; Cabrita, J.; Vargas, O.; Vermeylen, G.; Wilczynska, A.; Wilkens, M. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey–Overview Report (2017 update); Eurofound; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; ISBN 978-92-897-1597-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J.A.; Gerson, K. The Time Divide: Work, Family, and Gender Inequality; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The Current Population Survey (CPS). Available online: https://www.bls.gov/cps/lfcharacteristics.htm (accessed on 20 March 2016).

- Department of Population and Employment Statistics National Bureau of Statistics, P.R.C. China Labour Statistical Yearbook 2018; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Beckers, D.G.J. Overtime Work and Well-Being: Opening Up the Black Box; Tom Friedman: Courtesy Gagosian Gallery: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Qingbo, H.; Zhihong, S. The association between working hours and physical and mental health among rural-urban migrant work in China. China J. Health Psychol. 2015, 23, 358–362. [Google Scholar]

- Bannai, A.; Tamakoshi, A. The association between long working hours and health: A systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tanaka, H. Overtime work, insufficient sleep, and risk of non-fatal acute myocardial infarction in Japanese men. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 59, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparks, K.; Cooper, C.; Fried, Y.; Shirom, A. The effects of hours of work on health: A meta-analytic review. J. Occup. Org. Psychol. 1997, 70, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Chan, A.H.; Ngan, S. The effect of long working hours and overtime on occupational health: A meta-analysis of evidence from 1998 to 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès, I.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Cascant, L.; Villegas, R. Understanding the relationship of long working hours with health status and health-related behaviours. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scandura, T.A.; Lankau, M.J. Relationships of gender, family responsibility and flexible work hours to organizational commitment and job satisfaction. J. Org. Behav. 1997, 18, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Hou, C. Why work overtime? A systematic review on the evolutionary trend and influencing factors of work hours in China. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.M.; Stroh, L.K. Working 61 plus hours a week: Why do managers do it? J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, A.; Inoue, A.; Mafune, K.; Hiro, H. The effect of changes in overtime work hours on depressive symptoms among Japanese white-collar workers: A 2-year follow-up study. J. Occup. Health 2019, 61, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fitzgerald, J.B.; Jorgenson, A.K.; Clark, B. Energy consumption and working hours: A longitudinal study of developed and developing nations, 1990–2008. Environ. Soc. 2015, 1, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Cooke, F.L. Work–life balance in C hina? Social policy, employer strategy and individual coping mechanisms. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2012, 50, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, D.G.; van der Linden, D.; Smulders, P.G.; Kompier, M.A.; Taris, T.W.; Van Yperen, N.W. Distinguishing between overtime work and long workhours among full-time and part-time workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2007, 33, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ancona, D.G.; Goodman, P.S.; Lawrence, B.S.; Tushman, M.L. Time: A new research lens. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, D.G.; van Hooff, M.L.; van der Linden, D.; Kompier, M.A.; Taris, T.W.; Geurts, S.A. A diary study to open up the black box of overtime work among university faculty members. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2008, 34, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ancona, D.G.; Okhuysen, G.A.; Perlow, L.A. Taking time to integrate temporal research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Pettigrew, T.F. Advances in relative deprivation theory and research. Soc. Just. Res. 2015, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Pettigrew, T.F.; Pippin, G.M.; Bialosiewicz, S. Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, F.; Gonzalez-Intal, A.M. Relative deprivation and equity theories. In The Sense of Injustice; Folger, R., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Summing up: Relative deprivation as a key social psychological concept. In Relative Deprivation: Specification, Development, and Integration; Walker, I., Smith, H.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 351–373. [Google Scholar]

- Tougas, F.; Beaton, A.M. Personal and group relative deprivation. In Relative Deprivationon: Specification, Development, and Integration; Walker, I., Smith, H.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, F. A model of egoistical relative deprivation. Psychol. Rev. 1976, 83, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Ortiz, D.J. Is it just me? The different consequences of personal and group. In Relative Deprivationon: Specification, Development, and Integration; Walker, I., Smith, H.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Carleton, R.N. Subjective relative deprivation is associated with poorer physical and mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoogah, D.B. Why should I be left behind? Employees’ perceived relative deprivation and participation in development activities. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougas, F.; Veilleux, F. The influence of identification, collective relative deprivation, and procedure of implementation on women’s response to affirmative action: A causal modeling approach. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 1988, 20, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. The economic lives of the poor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Winden, W. The end of social exclusion? On information technology policy as a key to social inclusion in large European cities. Reg. Stud. 2001, 35, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Prooijen, J.W.; Van den Bos, K.; Wilke, H.A. Group belongingness and procedural justice: Social inclusion and exclusion by peers affects the psychology of voice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, T.R.; Lind, E.A. A relational model of authority in groups. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 115–191. [Google Scholar]

- Dembe, A.E.; Erickson, J.B.; Delbos, R.G.; Banks, S.M. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: New evidence from the United States. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orthner, D.K.; Mancini, J.A. Leisure impacts on family interaction and cohesion. J. Leis. Res. 1990, 22, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabriskie, R.B.; McCormick, B.P. The influences of family leisure patterns on perceptions of family functioning. Fam. Relat. 2001, 50, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, T.B.; Jacquart, M. Leisure-activity patterns and marital satisfaction: A further test. J. Marriage Fam. 1988, 50, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.M.; Havitz, M.E.; Delemere, F.M. “I decided to invest in my kids’ memories”: Family vacations, memories, and the social construction of the family. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2008, 8, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaw, S.M. Family leisure and changing ideologies of parenthood. Soc. Compass 2008, 2, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.M.; Dawson, D. Purposive leisure: Examining parental discourses on family activities. Leis. Stud. 2001, 23, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, K. Time, gender, and the negotiation of family schedules. Symb. Interact. 2002, 25, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellani, L.; D’Ambrosio, C. Deprivation, social exclusion and subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellezza, S.; Paharia, N.; Keinan, A. Conspicuous consumption of time: When busyness and lack of leisure time become a status symbol. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 118–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Krueger, A.B.; Schkade, D.; Schwarz, N.; Stone, A.A. Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science 2006, 312, 1908–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Imbens, G.W.; Rubin, D.B.; Sacerdote, B.I. Estimating the effect of unearned income on labor earnings, savings, and consumption: Evidence from a survey of lottery players. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 778–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, J. Sociology of leisure. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1980, 6, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, F. Preferences on worklife scheduling and work-leisure tradeoffs. Mon. Labor Rev. 1978, 101, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T.; Weiner, B. When people ask “why” questions, and the heuristics of attributional search. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 40, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A.; Van den Bos, K. When fairness works: Toward a general theory of uncertainty management. Res. Organ. Behav. 2002, 24, 181–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. MPlus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables—Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthñn & Muthñn: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wahba, M.A.; Bridwell, L.G. Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1976, 15, 212–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijman, T.F.; Mulder, G. Psychological aspects of workload. In A Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology; Wolff, C.D., Drenth, P.J.D., Henk, T., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998; pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts, S.A.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Janssen, O. Fairness perceptions as a moderator in the curvilinear relationships between job demands, and job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, O. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. J. Occup. Org. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bos, K. What is responsible for the fair process effect. In Handbook of Organizational Justice; Greenberg, J., Colquitt, J.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 273–300. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Braucks, J.; Baethge, A.; Dormann, C.; Vahle-Hinz, T. Get even and feel good? Moderating effects of justice sensitivity and counterproductive work behavior on the relationship between illegitimate tasks and self-esteem. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Luksyte, A.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J.; Wang, M. Overqualification and counterproductive work behaviors: Examining a moderated mediation model. J. Org. Behav. 2015, 36, 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.B.; Su, Q. Off-farm employment of rural labor force and land transfer in China: A study based on a dynamic perspective. Econ. Surv. 2012, 2, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Control Variables | |

| Gender | 1 = Male; 2 = Female |

| Age | Years |

| Marriage | Your marital status is: 1 = Unmarried; 2 = First marriage; 3 = Remarried; 4 = Divorced; 5 = Bereaved; 6 = Cohabitation |

| Annual income | Your total income in 2015 was (including agricultural income, wage income, operating income, etc.) RMB (Yuan). |

| Living type | Your living type is 1 = Rural, 2 = Urban |

| Overtime location | Usually, where do you work overtime? 1 = Workplace; 2 = Other places outside the workplace (such as dormitory, home, hotel, etc.) |

| Independent Variable | |

| Overtime | How many hours did you work overtime last month? |

| Dependent variables | |

| Subjective social status | In our society, some people are at the top, and some are at the bottom. There is a ladder from top to bottom on the card below. The highest “10” is the top, and the lowest “1” is the bottom. At which level do you think you are? |

| Social inclusion | Are you likely to settle here in the future? 1 = Very unlikely; 2 = Less likely; 3 = Not sure; 4 = More likely; 5 = Very likely |

| Moderating variables | |

| Overtime type | In general, which of the following situations do your overtime work meet? 0 = Overtime on working days; 1 = Overtime on rest days or legal holidays |

| Fairness | Do you think your current standard of living is fair with respect to your efforts at work? 1 = Completely fair; 2 = Fairly; 3 = Not fair but not unfair; 4 = Relatively unfair; 5 = Totally unfair |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 35.62 | 9.495 | ||||||||||

| 2. Gender | 1.39 | 0.488 | −0.100 * | |||||||||

| 3. Marriage | 1.88 | 0.804 | 0.338 ** | −0.028 | ||||||||

| 4. Income | 57,389.37 | 58,828.040 | 0.001 | −0.204 ** | 0.119 * | |||||||

| 5.Unit type | 1.77 | 0.423 | −0.029 | 0.013 | −0.001 | 0.177 ** | ||||||

| 6. Overtime type | 1.30 | 0.465 | −0.140 ** | 0.011 | 0.010 | −0.057 | 0.053 | |||||

| 7. Time type | 0.20 | 0.397 | 0.036 | −0.042 | 0.011 | 0.028 | −0.166 ** | 0.019 | ||||

| 8. Hours of overtime | 40.43 | 39.905 | −0.019 | −0.057 | −0.023 | −0.097 | −0.196 ** | −0.037 | −0.064 | |||

| 9. Fairness | 3.17 | 0.944 | −0.100 * | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.074 | −0.065 | −0.264** | −0.047 | −0.130 ** | ||

| 10. Social inclusion | 3.23 | 1.585 | 0.003 | −0.041 | 0.032 | −0.211 ** | −0.248* | 0.119* | 0.156** | −0.204 ** | 0.004 | |

| 11. Subjective social status | 4.11 | 1.784 | 0.009 | −0.007 | 0.072 | 0.249 ** | 0.055 | −0.053 | 0.057 | −0.132 ** | 0.200 ** | 0.200 ** |

| Variables | Subjective Social Status Model 1 | Social Inclusion Model 2 | Subjective Social Status Model 3 | Social Inclusion Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.816 ** | 1.292 ** | 4.020 ** | 1.541 ** |

| Age | 0.009 | −0.021 | 0.004 | −0.027 |

| Gender | 0.166 | −0.028 | 0.136 | −0.063 |

| Marriage | 0.095 | 0.027 | 0.093 | 0.025 |

| Income | 0.443 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.427 ** | 0.262 ** |

| Unit type | 0.053 | 0.788 ** | −0.029 | 0.688 ** |

| Overtime type | −0.157 | 0.410 * | −0.169 | 0.395* |

| Hours of overtime | −0.193 * | −0.235 ** | ||

| R | 0.260 | 0.324 | 0.280 | 0.354 |

| R2 | 0.067 | 0.105 | 0.079 | 0.126 |

| ΔR2 | 0.105 | 0.011 | 0.021 | |

| F | 4.734 ** | 7.662 ** | 4.776 ** | 8.048 ** |

| ΔF | 4.759 * | 9.379 ** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, C. Examining the Effects of Overtime Work on Subjective Social Status and Social Inclusion in the Chinese Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3265. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17093265

Chen Y, Li P, Yang C. Examining the Effects of Overtime Work on Subjective Social Status and Social Inclusion in the Chinese Context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(9):3265. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17093265

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yashuo, Pengbo Li, and Chunjiang Yang. 2020. "Examining the Effects of Overtime Work on Subjective Social Status and Social Inclusion in the Chinese Context" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 9: 3265. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph17093265