“It’s Like Juggling, Constantly Trying to Keep All Balls in the Air”: A Qualitative Study of the Support Needs of Working Caregivers Taking Care of Older Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment of Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

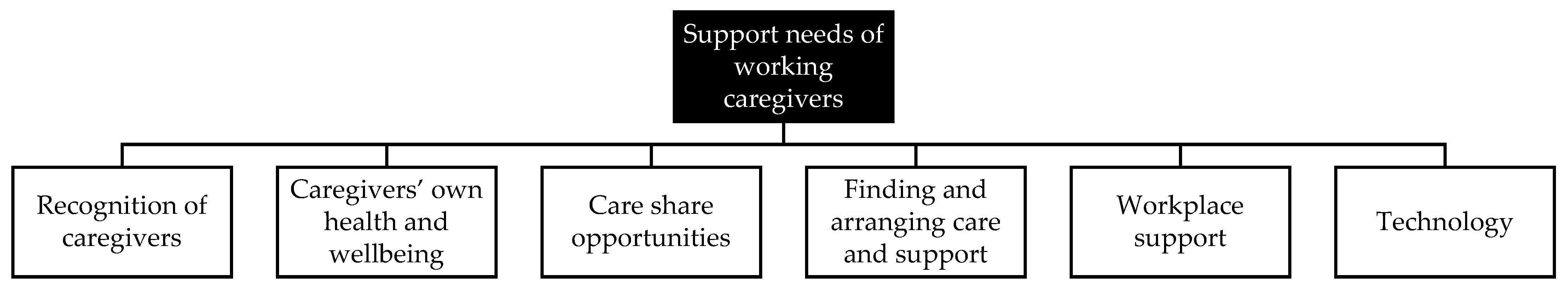

3.2. Support Needs of Working Caregivers

“Again, it’s about everyone being familiar with it. You know, it starts with awareness. If you don’t actually realize that you are a caregiver and whatever that entails, you know, you just do it, you take care of your loved ones anyway. And the situation presents itself and before you know it you are in the middle of it and you are so caught up in it, that you get sucked into that flow and only later on you find out, wow, that flow is fierce; what am I doing?” .(Part. 2 FGD 4, female)

“It was my son who said: ‘Now you have to slam on the brakes, because of course, Mom needs that care, but you don’t have to do it alone. You can get support for that.’ And it’s not like I was afraid to ask for help there, but it had never occurred to me. Never.”.(Part. 2 FGD 5, male)

“But you know, I never get any recognition. It’s all taken for granted. So if there is just a lot more attention for this from society, then I also think it is something that… In the end I think that every person wants to be recognized in that way too, and that you will be able to carry on longer in that case.”.(Part. 2 FGD 4, female)

“We have a societal issue here in the sense that we think that informal care is very important. So then it should be organized, right? Don’t go around saying, “Just be a caregiver, and how? Just go and figure it out for yourselves.” These people all have to reinvent the wheel, so why not make it a law, do something with it in the collective labor agreements so that it is protected, that you have rights as an informal caregiver. That it is a right, not only a duty and something you want, but also a right that you can and are allowed to do.”.(Part. 2, FGD 5, male)

“Well, you call twice a day, right? And during our holiday, we went to my mother-in-law, and I went to see my mother. And it just keeps you busy. You’re never completely away from it all.”.(Part. 3, FGD 5, female)

“Yes, [what I need] is only one thing and that is a sympathetic ear, someone who wants to listen to my side of the story only. It could be on the phone, or in a live chat. I wouldn’t mind if that’s planned, if I say, ‘I just need a little chat now,’ that we schedule that. I’m thinking of a coach or something along those lines, who is good at asking questions, is able to confront and also helps to maybe think about possible solutions [...] Someone who really notices: now you are of no use to anyone, now you have to take a break.”.(Part. 5, FGD 2, female)

“[I would like to] learn how to take good care of myself. Making sure that you don’t get completely exhausted. It would be good if this comes into the picture not just when you get stuck or are in danger of complete exhaustion or are getting close to a burnout, but much earlier. […] So that is also something that can be discussed when it comes to supporting the caregiver.”.(Part. 4, FGD 6, female)

“Networking before informal care is needed; a social basis is important. There is not enough attention being paid to that at the moment. Everything is focused on care and not on knowing each other, and sharing things with each other and staying out of care. [That’s why we need to] build a preventive network so that if something happens, then you have a network that is a logical interlocutor and considers it normal to offer support for a while.”.(Advisory board member, female)

“As an informal caregiver, you’re supposed to do that [arranging care] yourself, but you can’t. Certainly not if you don’t speak the language and certainly not if you’re new to it and don’t even know where to start. So then it really depends very much on: are you lucky enough to meet the right people who will take you by the hand and guide you and help you on your way? And if not, it is a real struggle to organize the right care and support at all before you get to… look after yourself as a caregiver. […] And the moment the care institutions are more prepared for that group of older migrants, this can ease the burden on caregivers more quickly.”.(Part. 4, FGD 6, female)

“You don’t know where to start, you want to help, but there are a hundred thousand regulations, a hundred thousand service counters, and how does it all work?”.(Part. 3, FGD 6, female)

“I just wish there was a central point, where someone is assigned to you. Someone who actually helps you to sort out how you can best get things organized. And who maybe also takes some steps in that sense. Because I think now it’s really… it’s enough to make you weep.”.(Part. 6, FGD 3, female)

“It would be so good if you had one service counter at the beginning, at the starting point. Or one person with whom you can get things started and who puts you on the right track, what the options are. So the starting point should be clearer and easier to find.”.(Part. 3, FGD 6, female)

“What I can expect and whether they think that my mother can continue to live independently. And if not, should I be taking steps now, should I go and start inquiries at the nursing home… Yes, all these things actually. What I should be considering and what I can work towards, as it were.”.(Part. 3, FGD 4, female)

“And I myself was thinking more about, well, understanding from your employer and your colleagues. You can try to explain… It’s sometimes very difficult to explain what’s happening to you, so that they can also better understand that some days you can do less—less of your work. That you’re there, but you’re not actually there.”.(Part. 4, FGD 2, female)

“Well, my most important need is really understanding. You know, understanding from your employer. When you are really busy with care, no matter for whom, that there is understanding and openness and ... safety, especially the safety of being able to share and talk about it. That sharing is encouraged, that you can also communicate and name it.”.(Part. 2, FGD 6, female)

“Over the years, I have experienced different reorganizations and had different managers. And usually I could count on the understanding and cooperation and flexibility of the manager. But I have also had a manager who had no sympathy at all. Who thought that those kinds of privileges should be stopped.”.(Part. 4, FGD 6, female)

“Yes, we had one of those sensors, like a chain, you know, that my mother could press if something happened in the house. It was linked to our phone numbers, but she just didn’t want that. She kept throwing it out and it was a waste of money, because you had to pay for it every month, for the switchboard. But for her, it had no added value.”(Part. 4, FGD 4, male)

“He just has those fingers with rheumatism, so it’s not always that easy. So if he has to do something on his tablet, it often goes like, you have to enter a code and then three of the four numbers are entered, but not the fourth and then it goes wrong again. And that can be a problem for him. So the tools are often not really geared to being used by the elderly.”.(Part. 2, FGD 2, female)

4. Discussion

4.1. Caregivers’ Personal Needs

4.2. Needs Within the Care and Support Context

4.3. Needs within the Work Environment

4.4. Timing of Support

4.5. Methodological Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rowland, D.T. Global Population Aging: History and Prospects. In International Handbook of Population Aging; Uhlenberg, P., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Farber, N.; Shinkle, D.; Lynott, J.; Fox-Grage, W.; Harrell, R. Aging in Place: A State Survey of Livability Policies and Practices; National Conference of State Legislatures and AARP Public Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Growing Need for Home Health Care for the Elderly: Home Health Care for the Elderly as an Integral Part of Primary Health Care Services; World Health Organization; Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: Cairo, Egypt, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for European Communities. Age and Attitudes. Main Results from a Eurobarometer Study; Commission for European Communities; Directorate-General V, Employment, Industrial Relations and Social Affairs: Brussels, Belgium, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrano, D.L.; Palmer, K.; Marengoni, A.; Marzetti, E.; Lattanzio, F.; Roller-Wirnsberger, R.; Lopez Samaniego, L.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Frailty and Multimorbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 74, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Broese van Groenou, M.I.; De Boer, A. Providing informal care in a changing society. Eur. J. Ageing 2016, 13, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Genet, N.; Boerma, W.; Kroneman, M.; Hutchinson, A.; Saltman, R.B. Home Care across Europe. Current Structure and Future Challenges; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, F.; Llena-Nozal, A.; Mercier, J.; Tjadens, F. Help Wanted? Providing and Paying for Long-Term Care; OECD Health Policy Studies: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard, S.; Levine, C.; Samis, S. Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care; AARP Public Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- de Klerk, M.; de Boer, A.; Plaisier, I.; Schyns, P. Voor elkaar? Stand van de Informele hulp in 2016 [For Each Other? The State of Informal Care in 2016]; The Netherlands Institute for Social Research: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CBS Statline. Informal Caregivers, Aged 16 and Over. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83021NED/table?dl=39BF1 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- de Boer, A.; Plaisier, I.; de Klerk, M. Werk en mantelzorg. Kwaliteit van leven en het gebruik van ondersteuning op het werk. [Work and Informal Care. Quality of Life and the Use of Support in the Workplace]; Netherlands Institute for Social Research: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, A.J.; Garip, G.; Sheffield, D. The psychosocial impact of caregiving in dementia and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Psychol. Health 2018, 33, 1321–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.A.; Colantonio, A.; Vernich, L. Positive aspects of caregiving: Rounding out the caregiver experience. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 2002, 17, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogstel, M.O.; Curry, L. Caring for Older Adults: The Benefits of Informal Family Caregiving. J. Theory. Constr. Test. 2005, 9, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.M.; Brown, S.L. Informal Caregiving: A Reappraisal of Effects on Caregivers. Soc. Issues Policy. Rev. 2014, 8, 74–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.M.; Sousa-Poza, A. Impacts of Informal Caregiving on Caregiver Employment, Health, and Family. J. Popul. Ageing 2015, 8, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, D.W.L. Effect of Financial Costs on Caregiving Burden of Family Caregivers of Older Adults. SAGE Open 2012, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brimblecombe, N.; Fernandez, J.L.; Knapp, M.; Rehill, A.; Wittenberg, R. Review of the international evidence on support for unpaid carers. J. Long Term Care 2018, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, M.B.; Laporte, A.; Coyte, P.C. Labor market work and home care’s unpaid caregivers: A systematic review of labor force participation rates, predictors of labor market withdrawal, and hours of work. Milbank Q 2007, 85, 641–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Boer, A.; van Groenou, M.B.; Keuzenkamp, S. Belasting van werkende mantelzorgers [Burden of working caregivers]. TSG 2010, 88, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Carers Research. Carer Wellbeing and Supports: A Review of the Literature and Directions for Research; Institute of Public Policy and Governance, University of Technology Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Suanet, B.; van Wieringen, M.; de Boer, A.; Beersma, B.; Taverne, O. Wie Zorgt Voor Degenen Die Zorgen? Naar Betere Mantelzorgondersteuning [Who Cares for Those Who Care? Towards Better Caregiver Support]; Institute for Societal Resilience: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, S.; Matlo, C.; Bobrovitskiy, C.; Waldoch, A.; Fang Mei, L.; Jackson, P.; Mihailidis, A.; Nygård, L.; Astell, A.; Sixsmith, A. Ambient Assisted Living Technologies for Aging Well: A Scoping Review. J. Intell. Syst. 2016, 25, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maaden, T.; de Bruijn, A.C.P.; Vonk, R.; Weda, M.; Koopmanschap, M.A.; Geertsma, R.E. Horizon Scan of Medical Technologies. Technologies with an Expected Impact on the Organisation and Expenditure of Healthcare; National Institute for Public Health and the Environment: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Plöthner, M.; Schmidt, K.; de Jong, L.; Zeidler, J.; Damm, K. Needs and preferences of informal caregivers regarding outpatient care for the elderly: A systematic literature review. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-I. Understanding Patterns of Service Utilization Among Informal Caregivers of Community Older Adults. Gerontologist 2009, 50, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Hartmann, M.; Wens, J.; Verhoeven, V.; Remmen, R. The effect of caregiver support interventions for informal caregivers of community-dwelling frail elderly: A systematic review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2012, 12, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verbakel, E. Informal caregiving and well-being in Europe: What can ease the negative consequences for caregivers? J. Eur. Soc. Policy. 2014, 24, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.; Femia, E. Behavioral and psychosocial interventions for family caregivers. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2008, 44, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen, S.; Pinquart, M.; Duberstein, P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobe, B. Best Practices for Synchronous Online Focus Groups. In A New Era in Focus Group Research, Barbour, R., Morgan, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 227–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, A.J. Interaction in cyberspace: An online focus group. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 49, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Gray, D. Innovations in Qualitative Methods. In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Social Psychology; Gough, B., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 243–266. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willemse, E.; Anthierens, S.; Farfan-Portet, M.I.; Schmitz, O.; Macq, J.; Bastiaens, H.; Dilles, T.; Remmen, R. Do informal caregivers for elderly in the community use support measures? A qualitative study in five European countries. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCabe, M.; You, E.; Tatangelo, G. Hearing Their Voice: A Systematic Review of Dementia Family Caregivers’ Needs. Gerontologist 2016, 56, e70–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joling, K.J.; Windle, G.; Dröes, R.-M.; Huisman, M.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; Woods, R.T. What are the essential features of resilience for informal caregivers of people living with dementia? A Delphi consensus examination. Aging. Ment. Health 2017, 21, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Ishado, E.; O’Hara, A.; Borson, S.; Sadak, T. Developing a Unifying Model of Resilience in Dementia Caregiving: A Scoping Review and Content Analysis. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 0733464820923549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaugler, J.E.; Kane, R.L.; Newcomer, R. Resilience and Transitions from Dementia Caregiving. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2007, 62, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minkman, M.M.N.; Ligthart, S.A.; Huijsman, R. Integrated dementia care in The Netherlands: A multiple case study of case management programmes. Health Soc. Care Community 2009, 17, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balard, F.; Gely-Nargeot, M.-C.; Corvol, A.; Saint-Jean, O.; Somme, D. Case management for the elderly with complex needs: Cross-linking the views of their role held by elderly people, their informal caregivers and the case managers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lyons, K.S.; Zarit, S.H.; Sayer, A.G.; Whitlatch, C.J. Caregiving as a Dyadic Process: Perspectives from Caregiver and Receiver. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, J.L.; Kasper, J.D.; Shore, A.D. Long-Term Care Preferences among Older Adults: A Moving Target? J. Eur. Soc. Policy. 2008, 20, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, M.; Phillips, J.E. Working carers of older adults. Community Work Fam. 2007, 10, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; Kemp, P.; Glendinning, C.; Kotchetkova, I.; Tozer, R. Carers’ Aspirations and Decisions around Work and Retirement (Research Report 290); Department for Work and Pensions: Leeds, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann, C.; Zacher, H. Supporting employees with caregiving responsibilities. In Creating Psychologically Healthy Workplaces; Burke, R.J., Richardsen, A.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 431–451. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, R.; Dardas, A.Z.; Wang, L.; Williams, A. Evaluation of a Caregiver-Friendly Workplace Program Intervention on the Health of Full-Time Caregiver Employees. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, e548–e558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtelt, P.V.; Croezen, S.; Vlasblom, J.D.; Voogd-Hamelink, M.D. Aanbod van Arbeid. Werken, Zorgen en Leren op Een Flexibele Arbeidsmarkt [Supply of Labor. Working, Caring and Learning in a Flexible Labor Market]; The Netherlands Institute for Social Research: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, M.E.; Tennstedt, S.; Chang, B.-H. Contributors to and Mediators of Psychological Well-Being for Informal Caregivers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 1999, 54B, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Question 1 | What are your experiences and what challenges do you encounter, while combining work, life and care? |

| Question 2 | What are your support needs as a working caregiver, and how can your needs be met? |

| Question 3 | How can technology or ‘e-health’ be used to support you as a working caregiver? |

| Question 4 | What constitutes good caregiver support according to you? |

| Question 5 | What can be done to help working caregivers who need support, to find their way to the right support in a timely manner? |

| Total (n = 25) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 22 |

| Male | 3 |

| Hours of Caregiving Per Week | |

| 1–10 h | 14 |

| 11–20 h | 6 |

| 21–30 h | 3 |

| >30 h | 2 |

| Educational Level | |

| Unknown 1 | 1 |

| Low educational level | 0 |

| Middle educational level | 4 |

| High educational level | 20 |

| Hours of Paid Work Per Week | |

| <20 h 2 | 5 |

| 20–30 h | 9 |

| 31–40 h | 9 |

| >40 h | 2 |

| Employment | |

| Not currently working 2 | 3 |

| Salaried employment | 14 |

| Self-employed | 7 |

| Self-employed and in salaried employment | 1 |

| I am Satisfied with How I am Able to Combine Work and Care | |

| Strongly agree | 3 |

| Agree | 9 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 7 |

| Disagree | 4 |

| Strongly disagree | 2 |

| Home and Social Environment: |

|

| Care and Support Environment: |

| Information: |

|

| Services: |

|

| Process improvements: |

|

| Work Environment: |

|

| Societal/Policy Environment: |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vos, E.E.; de Bruin, S.R.; van der Beek, A.J.; Proper, K.I. “It’s Like Juggling, Constantly Trying to Keep All Balls in the Air”: A Qualitative Study of the Support Needs of Working Caregivers Taking Care of Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5701. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18115701

Vos EE, de Bruin SR, van der Beek AJ, Proper KI. “It’s Like Juggling, Constantly Trying to Keep All Balls in the Air”: A Qualitative Study of the Support Needs of Working Caregivers Taking Care of Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5701. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18115701

Chicago/Turabian StyleVos, Eline E., Simone R. de Bruin, Allard J. van der Beek, and Karin I. Proper. 2021. "“It’s Like Juggling, Constantly Trying to Keep All Balls in the Air”: A Qualitative Study of the Support Needs of Working Caregivers Taking Care of Older Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5701. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18115701