Eco Trends, Counseling and Applied Ecology in Community Using Sophia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Q1:

- What are the characteristics of the practices applied in the form of counseling in the two areas analyzed?

- Q2:

- What are the current trends in each area regarding the use of ecological concepts and environmental protection?

- Q3:

- Can these trends be considered as conceptual innovations or adaptations of applied practice in the two areas analyzed, and if they can they be oriented to the benefit of communities?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Nature and Ecology in Philosophy and Theology

2.2. Counseling, as a Form of Practice in the Two Areas

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Analysis about the Philosophical Counseling Versus Spiritual Counseling

4.2. Bibliometric Analysis on the Concepts of Ecophilosophy and Ecotheology

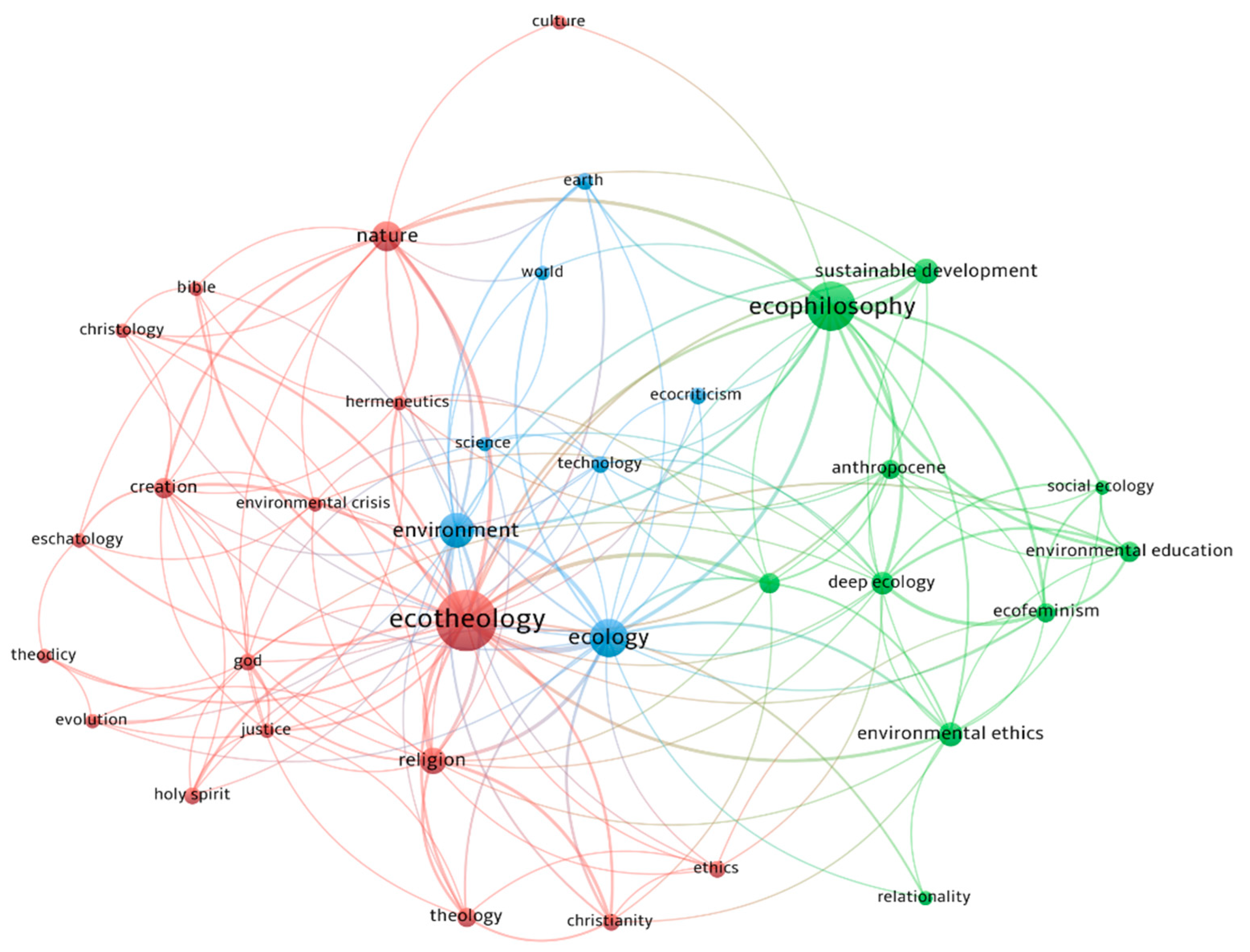

4.2.1. Analysis by Keywords

4.2.2. Analysis by Authors and Countries

4.2.3. Citations by Authors Analysis

5. Discussion and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reale, G. Istoria Filosofiei Antice; Galaxia Gutenberg: Târgu Lăpuș, România, 2021; Volume 9, pp. 205–375. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, P. Ce Este Filosofia Antică? Trei: București, Romania, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, P. Exercices Spirituels et Philosophie Antique; Albin Michel: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Collinkwood, R.G. Ideea de Natură. O Istorie a Gândirii Cosmologice Europene; Herald: București, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Larchet, J.C. Fundamentele Spirituale ale Crizei Ecologice; Sophia: București, Romania, 2019; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Berdiaev, N. Sensul Vieții; Humanitas: București, Romania, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ivlampie, I. Spiritualismul Rus în Secolul XX; Eikon: București, Romania, 2015; p. 226. [Google Scholar]

- Berdiaev, N. Cunoasterea de Sine, Exercitiu de Autobiografie Filosofică; Humanitas: București, Romania, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Routledge Classics Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sabašinskaite, J. Eco-Philosophy, the extension of perception and the value of nature. Topos 2013, 3, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, A. Spinoza and ecology. Philosophia 1977, 7, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoenescu, C. Etica Mediului. Argumente Rezonabile si Întampinari Critice; Institutul European: Iași, Romania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Descartes, R. Discurs Asupra Metodei; Editura Științifică: București, Romania, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, W. The Philosophy Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained; DK Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Callicott, J.B. (Ed.) Companion to a Sand County Almanac; University of Winsconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Callicott, J.B. Animal Liberation. A triunghiular affair. Environ. Ethics 1980, 2, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, R.B. The Greening of Protestant Thought; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, R. This Sacred Earth; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsley, D. Ecology and Religion. Ecological Spirituality in Cross-Cultural Perspective; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, S.H. Religion and the Order of Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Northcott, M. The Environment and Christian Ethics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, A. The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement. A summary. Inquiry 1973, 16, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, A.; Ecosophy, T. Environmental Ethics; Pojman, L., Ed.; Wadsworth: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Drengson, A.; Devall, B. The Ecology of Wisdom: Writings by Arne Naess; Counterpoint: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, A. The Deep Ecological Movement: Some Philosophical Aspects. In Environmental Philosophy; Zimmerman, E.A., Ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Sessions, G. (Ed.) Deep Ecology for the Twenty-First Century; Sambala: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi, R. Introduction to Integrating Philosophy and Ecology: Biocultural Interfaces. In Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World. Values, Philosophy, and Action; Rozzi, E.A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi, R. Biocultural Ethics: From Biocultural Homogenization toward Biocultural Conservation. In Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World. Values, Philosophy, and Action; Rozzi, E.A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, D.; Golley, F. The Philosophy of Ecology: From Science to Synthesis; University of Georgia Press: Athens, Greece, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Justus, J. Philosophical Issues in Ecology. In The Philosophy of Biology: A Companion for Educators; History, Philosophy and Theory of the Life Sciences; Kampourakis, K., Ed.; Springer Science + Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 343–372. [Google Scholar]

- Skolimowski, H. Eco–Philosophy; Marion Boyars: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Papuzinski, A. The Idea of Philosophy vs. Eco-Philosophy. Probl. Ekorozw. 2009, 4, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hațegan, V. Promoting the Eco-Dialogue through Eco-Philosophy for Community. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroe, C. Statutul ecosofiei și al ecologiei din perspectiva raporturilor cu filosofia. Rev. Filos. 2009, LVI, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Capcelea, V. Filosofia Socială; Pro Universitaria: București, Romania, 2019; p. 302. [Google Scholar]

- Soloviov, N. Rusia și Biserica Universală; Institutul European: Iași, România, 1994; p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, F. The Ecological Self; Routledge: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Soloviov, N. Temeiurile Duhovnicești Ale Vieții, 2nd ed.; Deisis: Sibiu, Romania, 2018; p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- Cordoneanu, I. În Dialog. Studii de Filosofie Creștină, Teologie Politică și Istoria Religiei; Eikon: București, Romania, 2015; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Conradie, E.M. The four tasks of Christian Ecotheology: Revisiting the current debate. Scriptura 2020, 119, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, J. About a theology of conservation. Faith Freedom J. Progress. Relig. 1985, 38, 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Balasuriya, T. Planetary Theology; SCM Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, M. (Ed.) An Ecology of the Spirit: Religious Reflection and Environmental Consciousness; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bauckham, R. First Step to a Theology of Nature. Evang. Q. 1986, 58, 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J. Toward a Theology for the Environment. Baptist Q. 1991, 34, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braaten, C.E. Toward an Ecological Theology. In Christ and Counter-Christ: Apocalyptic Themes in Theology and Culture; Fortress Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1972; Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bratton, S.P. The Ecotheology of James Watt. Environ. Ethics 1983, 5, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratton, S.P. Christian Ecotheology and the Old Testament. Environ. Ethics 1984, 5, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.H. Ecological Sin. Theol. Today 1992, 49, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, P. Challenges in the Search for an Ecotheology. OTE 2009, 22, 186–204. [Google Scholar]

- Deane-Drummond, C. Eco-Theology; Saint Mary’s Press: Winona, MN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oprea, C.; Ciocan, T.C. Ecotheological applicative researches. Proc. Dialogo 2016, 3, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, C.; Ciocan, T.C.; Oprea, A. The Ecotheological Consciousness in Environmental Studies. Proc. Dialogo 2017, 3, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, A. Consilierea Filosofică Apreciativă; Lumen: Iasi, Romania, 2019; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Tomuleț, D. Reflecții sumare asupra relației dintre teologie și filosofie. In Simetriile Înțelepciunii. Studii de filosofie și Teologie; Tat, A.E.A., Ed.; Eikon: București, Romania, 2017; pp. 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, G. Das Kleine Buch der Inneren Ruhe; Herder: Freiburg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hațegan, V. Practitioner Philosopher or Philosophical Counselor, options for new profession in Romania. Rev. Roum. Philos. 2018, 62, 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lahav, R. Oltre la Filosofia. Alla Ricerca della Saggezza; Apogeo: Milano, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nave, L. Il Counseling. Comunicazione e Relazione nell’incontro con L’altro; Xenia: Milano, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, J.D. Philosophy and Theology; Abingdon Press: Nashville, TN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Koestenbaum, P. The Philosophic Consultant. Revolutionizing Organizations with Idea; Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, P. Exerciții Spirituale și Filosofie Antică; Editura Sfântul Nectarie: Arad, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vegleris, E. La Consultation Philosophique: L’Art d’Éclairer l’Existence; Eyrolles: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hațegan, V. Therapy or counseling? Current directions of the philosophical practice. Rev. Roum. Philos. 2019, 63, 367–382. [Google Scholar]

- GilliganCoudy, M. Counsellors’ Skills in Existentialism and Spirituality; Balboa Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sautet, M. Un Cafe pour Socrate; R. Laffont: Paris, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lahav, R. Manualetto di Filosofia Contemplativa; Solfanelli: Chieti, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, D.J. Philosophical counselling: Towards a new approach in pastoral care and counselling? HTS Theol. Stud. 2011, 67, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frunză, S. Comunicare și Consiliere Filosofică; Eikon: Bucuresti, Romania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Faiver, C.; Ingersoll, R.E.; O’Brien, E.; McNally, C. Explorations in Counseling and Spirituality. In Philosophical, Practical and Personal Reflections; Brooks/Cole/Thomson Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deusen-Hunsinger, D. Theology and Pastoral Counseling: A New Interdisciplinary Approach; Wm. B. Eerdmans: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hategan, V. Consilierea Filosofică, de la Practica la Profesie; Ars Docendi: Bucuresti, Romania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Frunză, S. Philosophy, Spirituality, Therapy. J. Study Relig. Ideol. 2018, 17, 162–178. [Google Scholar]

- Cavadi, A. La Filosofia-in-Pratica e la Spiritualita Contemporanea. In Sofia e Agape; Zanella, C., Ed.; Liguori: Napoli, Italy, 2012; pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pollastri, N. Il Pensiero e la Vita; Apogeo: Milano, Italy, 2004; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Cavadi, A. Filosofia di Strada; Di Girolamo: Trapani, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zanella, C. Pratica pastorale cattolica e consulenza filosofica: Affinita e differenze nell’ accompagnamento pastorale. In Sofia e Agape; Zanella, C., Ed.; Liguori: Napoli, Italy, 2012; pp. 75–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hațegan, V. The practice of counseling between philosophy and spirituality, an interdisciplinary approach. J. Study Relig. Ideol. 2021, 20, 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Will non-humans be saved? An argument in ecotheology. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2009, 15, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harison, P. Subduing the Earth: Genesis 1, Early Modern Science, and the Exploitation of Nature. J. Relig. 1999, 79, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, E.; White, L. Ecotheology, and History-Discussion. Environ. Ethics 1993, 15, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather, P.G. Links between ecology and ecophilosophy, ethics and the requirements of environmental management. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, W. Transpersonal ecology: “psychologizing” ecophilosophy. J. Transpers. Psychol. 1990, 2, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Bratton, S.P. Eco-Dimensionality as a Religious Foundation for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riley, M.T. The democratic roots of our ecological crisis: Lynn White, biodemocracy, and the Earth Charter. Zygon 2014, 49, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrad, C. Constraints and Consequences of Online Teaching. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnaru, G.I.; Niță, V.; Anichiti, A.; Brînză, G. The Effectiveness of Online Education during Covid 19 Pandemic—A Comparative Analysis between the Perceptions of Academic Students and High School Students from Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comparative Elements/Features | Spiritual Counseling | Philosophical Counseling |

|---|---|---|

| The context of the activity | Belonging to the church/cult | Without determined context |

| The purpose of the action | Permanent active service, parish type, with missionary vocation | Practices based on instruments of philosophy and transferred by philosophers to counseling |

| The destination of the action | Christian community | Customers individuals or groups of people |

| The object of the action | The person’s relationship with the divinity. It produces changes in counselee thinking | The life examined/supports the clarification of the vision about the world and the person’s life |

| Main way of working | It is based on listening/dialogue | Through individual/collective dialogue |

| The professionalism | No deontological norms | A code of ethics is applied |

| The trend of professionalization | Remains attached to the church/parish | It can be regulated as a specialized public service |

| Operator training | The specialist comes from the parish, has theological studies no continuous training required | Philosophers who become practitioners or specialists trained in philosophical counseling, they need to follow continuous training |

| Freedom of conscience of the operator | In agreement with love for/relationship with the divinity (agape) | It derives from the worldview of the philosopher/client |

| Organizational destination | Less/Can be applied to groups of parishioner | Applies to organizations/institutions/communities |

| The meaning of the action | What does the world of the believer looks like? | Analysis of life in all its forms |

| Listening of the persons by the operator | With empathy/warm/encouraging. Try to reveal the person’s past in his approach | It is included in the dialogue of the parties, a compassion is manifested, in the form of a friendship of intellectual nature |

| How one can activate the person’s resources | By stigmatizing negative actions | By stimulating positive actions |

| Operating requirements | Attached to the church/parish, using the existing material base | Requires a location/office set up for counseling process |

| Type of the service provided | Free of charge | Onerous, the fee payment |

| Cluster 1 (Red) | Cluster 2 (Blue) | Cluster 3 (Green) |

|---|---|---|

| Ecotheology | Ecophilosophy | Ecology |

| Nature | Sustainable development | Environment |

| Religion | Deep ecology | Earth |

| Creation | Climate change | Eco-criticism |

| Theology | Environmental ethics | Technology |

| Author | Documents | Citations | Average Citations | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latour, B. | 1 | 45 | 4.02 | Ecotheology |

| Harrison, P. | 1 | 41 | 2.28 | Religion |

| Whitney, E. | 2 | 37 | 3.01 | Ecotheology |

| Fairweather, P.G. | 1 | 33 | 1.47 | Ecophilosophy |

| Francis, G. | 1 | 25 | 1.11 | Ecology |

| Hull, Z. | 2 | 24 | 5.45 | Sustainable development |

| Rozzi, R. | 1 | 24 | 7.38 | Ecology |

| Riley, M. T. | 3 | 17 | 9.62 | Ecology |

| Wersal, I. | 1 | 16 | 2.09 | Environmental ethics |

| Fox, W. | 1 | 13 | 3.25 | Ecophilosophy |

| Bratton, S. | 2 | 11 | 2.11 | Ecotheology |

| Skrimshire, S. | 1 | 11 | 2.40 | Climate change |

| Booth, A. | 2 | 10 | 2.44 | Environmental spirituality |

| Piatek, Z. | 3 | 10 | 5.14 | Ecology |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hategan, V.-P. Eco Trends, Counseling and Applied Ecology in Community Using Sophia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6572. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18126572

Hategan V-P. Eco Trends, Counseling and Applied Ecology in Community Using Sophia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6572. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18126572

Chicago/Turabian StyleHategan, Vasile-Petru. 2021. "Eco Trends, Counseling and Applied Ecology in Community Using Sophia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6572. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18126572