“It Is Like Medicine”: Using Sports to Promote Adult Women’s Health in Rural Kenya

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Quantitative Phase

2.2.1. Sample

2.2.2. Measures

2.2.3. Data Analysis Plan

2.3. Qualitative Phase

Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Findings

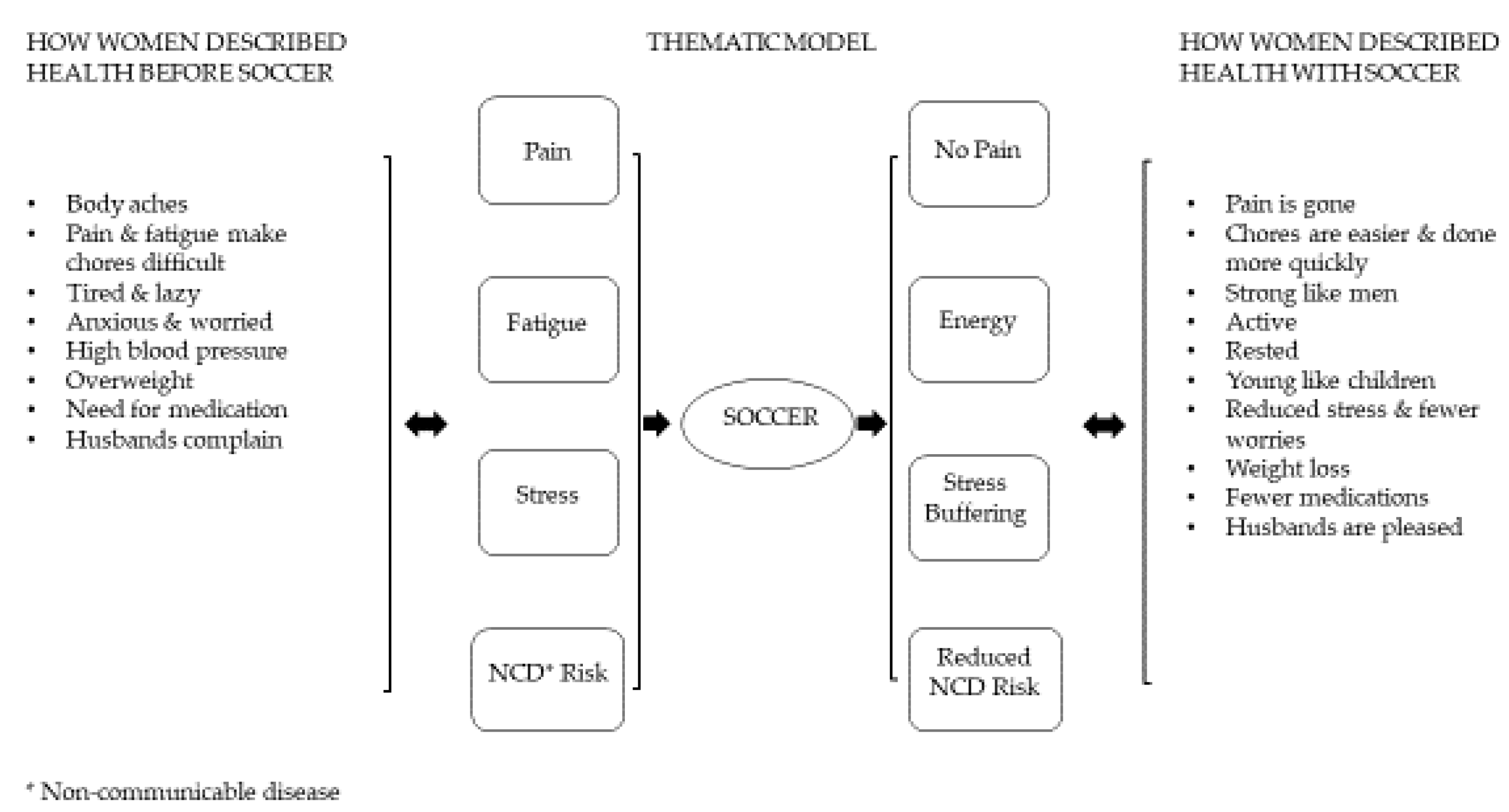

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. “I Can Feel the Difference, No More Back Pains” (KIW1-R2)

When I started playing football, I used to feel pain in my leg, but when I continued playing I am grateful that I stopped feeling the pain. I had waist complications, my husband would complain every time when I am not good in bed. When, however, I continued playing football, I am grateful, he does not complain any more.(PEW2-R3)

Before I could not even turn in bed when I am sleeping. When I go to fetch water, I would come back with back pains but when I started this exercise, even if you tell me to go fetch ten buckets I do not see a problem. Even my husband says that since I started playing soccer, I finish all my work fast.(JIW2-R1)

3.2.2. “I No Longer Feel Sleepy Because Playing Gave Me Strength.” (MAW1-R7)

Having joined the team, I feel strong and able to do my work much more easily. I used to sleep all the time and now I can do my work. For example, ploughing my gardens, milking cows, and fetching firewood without getting tired easily. Even when walking I feel good.(MAW1-R3)

…we play football just the same way [men] do. If it is getting into the field and running, we do the same. We kick the ball just as they do. They compete in tournaments as we do so I think it is just the same. Secondly when I leave the field and go home, there is no chore that I cannot do, so we are the same.(MGW1-R3)

Before I started playing soccer, my body was quite heavy. I would get tired from walking very short distances. It is as though I was very old. I was not even able to do some house chores because I would get tired very fast. But after I joined, I felt my body was lighter. Even if I wake up at four in the morning and sleep at 11 at night my body can handle it. Playing soccer has really helped us to be quick; there is no work we can say we are unable to do.(GOW2-R8)

When you play football, you do not age. We even went to play somewhere to compete, and some of us here were referred to as girls. The truth is that some have three or four children.(JUW1-R6)

3.2.3. “It Has Helped Us Because a Woman Leaves Her Home with a Lot in Her Head but When She Mixes with the Others, the Stress Goes Away.” (LUW2-R4)

When you stay at home, you have a lot of thoughts. When you fight with your husband, you become so stressed. If you do not have anything to do, you start thinking about the fight you had with your husband and as a result you become more stressed. But when you get to the field and play with your friends, you forget all that. Staying at home you become stressed because you are idle, but when you are playing you become like a small child and you have fun.(JIW1-R8)

I used to have a lot of stress, but when I go play, I come back happy, and the thoughts are gone.(MAW2-R11)

3.2.4. “Exercising Has Improved My Health. I No Longer Fall Ill with Common Diseases.” (MGW1-R7)

I will also add to that. For me I would lack sleep at times. I do not know if it was stress or what it may have been. I had to take Piriton [an analgesic] or paracetamol [acetaminophen], but now since I started ball, I don’t take medicine. When I go to sleep, I sleep as though I have taken Piriton. I mean it is Piriton. Let’s say it is like medicine now [laughter].(LUW1-R12)

High blood pressure was a major problem. The doctor used to encourage me to lose weight. I never used to eat a lot but the weight was constant. Since I joined the soccer team, my body has become more active and more fit. My pressure has decreased. I do not take the medicine anymore.(MPW2-R9)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goal 3. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3 (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Nugent, R.; Bertram, M.Y.; Jan, S.; Niessen, L.W.; Sassi, F.; Jamison, D.T.; Pier, E.G.; Beaglehole, R. Investing in non-communicable disease prevention and management to advance the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 2018, 391, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaacks, L.M.; Slining, M.M.; Popkin, B.M. Recent underweight and overweight trends by rural–urban residence among women in low-and middle-income countries. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC)—Africa Working Group. Trends in obesity and diabetes across Africa from 1980 to 2014: An analysis of pooled population-based studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goedecke, J.H.; Mtintsilana, A.; Dlamini, S.N.; Kengne, A.P. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in African women. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 123, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Division of Communicable Diseases, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; World Health Organization. Kenya STEPwise Survey for Non Communicable Diseases Risk Factors 2015 Report 2016; Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; p. 182.

- World Health Organization. UN, Kenyan Government Take Broad-Based Approach to Fighting NCDs. March 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/events/2014/kenya-ncd-prevention/en/ (accessed on 29 March 2020).

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health. Kenya National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2015–2020; Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; p. 80.

- Kruger, H.S.; Venter, C.S.; Vorster, H.H.; Margetts, B.M. Physical inactivity is the major determinant of obesity in black women in the North West Province, South Africa: The THUSA study. Nutrition 2002, 18, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, C. Women, poverty and sport: A South African scenario. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2002, 11, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, A.-R.; Bhopal, R. Systematic review on the prevalence of diabetes, overweight/obesity and physical inactivity in Ghanaians and Nigerians. Public Health 2008, 122, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobngwi, E.; Mbanya, J.N.; Unwin, N.C.; Kengne, A.P.; Fezeu, L.; Minkoulou, E.M.; Aspray, T.J.; Alberti, K.G.M.M. Physical activity and its relationship with obesity, hypertension and diabetes in urban and rural Cameroon. Int. J. Obes. 2002, 26, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Micklesfield, L.K.; Lambert, E.V.; Hume, D.J.; Chantler, S.; Pienaar, P.R.; Dickie, K.; Goedecke, J.H.; Puoane, T. Socio-cultural, environmental and behavioural determinants of obesity in black South African women. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2013, 24, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Puoane, T.; Matwa, P.; Hughes, G.; Bradley, H.A. Socio-cultural factors influencing food consumption patterns in the black African population in an urban township in South Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 14, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- County Government of Kwale. Kwale County Integrated Development Plan (2018–2022); Department of Finance and Planning, Kwale County Government: Kwale, Kenya, 2018.

- Otieno, G.A.; Owenga, J.A.; Onguru, D. Maternal Health Care Choices among Women in Lunga Lunga Sub County in Kwale County-Kenya. World J. Innov. Res. 2020, 8, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health. Kwale County, Health at a Glance. 2015. Available online: https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/291/Kwale%20County-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Alonso, A.; Langle de Paz, T. Health by All Means: Women Turning Structural Violence into Peace and Wellbeing; DEEP Education Press: Blue Mounds, WI, USA, 2019; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; StataCorp, LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- White, I.R.; Royston, P.; Wood, A.M. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat. Med. 2011, 30, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Survey Nonresponse; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christensen, D.L.; Faurholt-Jepsen, D.; Boit, M.K.; Mwaniki, D.L.; Kilonzo, B.; Tetens, I.; Kiplamai, F.K.; Cheruiyot, S.C.; Friis, H.; Borch-Johnsen, K.; et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and physical activity in Luo, Kamba, and Maasai of rural Kenya. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2012, 24, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coast, E. Maasai Demography; University of London: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aljassim, N.; Ostini, R. Health literacy in rural and urban populations: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2142–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Health and Development through physical Activity and Sport; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, S.; Van Ommeren, M.; Tang, K.C.; Armstrong, T.P. Mental health benefits of physical activity. J. Mental Health 2005, 14, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchi, F.; AbiNader, M.A.; Winter, S.C.; Obara, L.M.; Mbogo, D.; Thomas, B.M.; Ammerman, B. “When You Mix with Your Friends, All the Stress Is Gone”: Adult Women’s Soccer as a Social Support Intervention in Rural Kenya; Unpublished manuscript.

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Values | Self-Reported Health Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good to Excellent | Poor to Fair | ||||||

| n | % | % | % | χ2 | % | ||

| Soccer membership | 17.7 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 455 | 66.5 | 53.9 | 46.2 | |||

| Yes | 229 | 33.5 | 70.6 | 29.4 | |||

| Missing | - | - | |||||

| Self-reported health status | - | - | |||||

| Fair or poor | 277 | 40.5 | - | - | |||

| Good or excellent | 406 | 59.4 | - | - | |||

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 | |||||

| Age | 43.84 | <0.001 | |||||

| 18–24 years | 57 | 8.3 | 4.7 | 12.5 | |||

| 25–34 years | 157 | 23.0 | 16.3 | 31.9 | |||

| 35–49 years | 263 | 38.5 | 46.3 | 39.6 | |||

| 50–59 years | 86 | 12.6 | 19.5 | 10.0 | |||

| 60 years or older | 56 | 8.2 | 13.2 | 6.1 | |||

| Missing | 65 | 9.5 | |||||

| Relationship status | 13.97 | 0.001 | |||||

| Married | 536 | 78.4 | 75.0 | 81.2 | |||

| Partnered but not married | 31 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 5.9 | |||

| Not in a relationship | 114 | 16.7 | 22.5 | 12.9 | |||

| Missing | 3 | 0.4 | |||||

| Children | 13.87 | 0.003 | |||||

| None | 17 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.8 | |||

| 1–2 | 89 | 13.0 | 7.9 | 17.2 | |||

| 3–5 | 355 | 51.9 | 59.9 | 49.4 | |||

| 6 or more | 202 | 29.5 | 30.0 | 30.6 | |||

| Missing | 21 | 3.1 | |||||

| Education | 16.35 | 0.003 | |||||

| None | 268 | 39.2 | 30.8 | 46.0 | |||

| Some primary | 209 | 30.6 | 34.4 | 28.8 | |||

| Completed primary | 129 | 18.9 | 22.7 | 16.5 | |||

| Some secondary | 22 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.0 | |||

| Completed secondary or higher | 46 | 6.7 | 8.4 | 5.8 | |||

| Missing | 10 | 1.5 | |||||

| Work for wages in past 12 months | 7.86 | 0.020 | |||||

| No work for wages | 481 | 70.3 | 73.1 | 72.3 | |||

| Worked throughout year | 65 | 9.5 | 6.3 | 12.2 | |||

| Worked seasonally/occasionally | 117 | 17.1 | 20.5 | 15.5 | |||

| Missing | 21 | 3.1 | |||||

| Type of community | 61.76 | <0.001 | |||||

| Maasai | 95 | 13.9 | 2.5 | 21.7 | |||

| Maasai/settled | 47 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 8.9 | |||

| Settled | 471 | 68.9 | 82.3 | 59.6 | |||

| Market town | 71 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 9.9 | |||

| Missing | - | - | |||||

| Health clinic in community | 3.32 | 0.069 | |||||

| No | 515 | 75.3 | 57.2 | 42.8 | |||

| Yes | 156 | 22.8 | 65.4 | 34.6 | |||

| Missing | 13 | 1.9 | |||||

| Pain in past 4 weeks interfered with normal work | 69.49 | .000 | |||||

| Quite a bit/extremely | 112 | 16.4 | 25.7 | 10.1 | |||

| Moderately | 89 | 13.0 | 21.4 | 7.4 | |||

| Not at all/slightly | 482 | 70.5 | 52.9 | 82.5 | |||

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 | |||||

| Health in past 4 weeks limited moderate activities | 25.04 | 0.000 | |||||

| Limited a lot | 50 | 7.3 | 11.4 | 4.7 | |||

| Limited a little | 260 | 38.0 | 45.4 | 33.9 | |||

| Did not limit at all | 365 | 53.4 | 43.2 | 61.4 | |||

| Missing | 9 | 1.3 | |||||

| During past 4 weeks, did you have a lot of energy? | 40.82 | <0.001 | |||||

| A good bit/all of time | 395 | 57.8 | 28.6 | 13.8 | |||

| Some of time | 153 | 22.4 | 27.9 | 18.7 | |||

| None/a little of time | 135 | 19.7 | 43.5 | 67.5 | |||

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 | |||||

| During past 4 weeks, have you felt downhearted and blue? | 54.94 | 0.000 | |||||

| A good bit/all of time | 191 | 27.9 | 40.6 | 19.3 | |||

| Some of time | 123 | 18.0 | 22.1 | 15.3 | |||

| None/a little of time | 368 | 53.9 | 37.3 | 65.4 | |||

| Missing | 2 | 0.3 | |||||

| Amount of time physical or emotional health interfered with social activities in past 4 weeks | 30.92 | <0.001 | |||||

| A good bit/all of time | 105 | 15.4 | 24.5 | 9.4 | |||

| Some of time | 73 | 10.7 | 12.04 | 9.9 | |||

| None or a little of time | 500 | 73.1 | 63.5 | 80.7 | |||

| Missing | 6 | 0.9 | |||||

| OR | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soccer team participation (ref. Not in soccer) | 1.66 | 0.021 | 1.08, 2.57 |

| Type of community (ref. Settled village) | |||

| Maasai | 11.24 | <0.001 | 4.49, 28.14 |

| Maasai/Settled | 2.75 | 0.020 | 1.18, 6.43 |

| Market town | 1.88 | 0.053 | 0.99. 3.55 |

| Age (ref. 35 to 49 years) | |||

| 18 to 24 | 1.13 | 0.820 | 0.39, 3.25 |

| 25 to 34 | 1.86 | 0.028 | 0.07, 3.24 |

| 50 to 59 | 0.74 | 0.330 | 0.41, 1.35 |

| 60 and over | 0.56 | 0.129 | 0.27, 1.18 |

| Number of children (ref. 1 to 2) | |||

| None | 1.75 | 0.488 | 0.36, 8.59 |

| 3 to 5 | 2.37 | 0.021 | 1.14, 4.94 |

| 6 or more | 1.47 | 0.099 | 0.93, 2.33 |

| Relationship status (ref. Married) | |||

| Partnered, not married | 2.16 | 0.124 | 0.81, 5.77 |

| Not in relationship | 0.90 | 0.704 | 0.53, 1.53 |

| Education (ref. None) | |||

| Some primary | 0.72 | 0.186 | 0.44, 1.17 |

| Completed primary | 0.60 | 0.085 | 0.33, 1.07 |

| Some secondary | 0.68 | 0.485 | 0.24, 1.98 |

| Completed secondary or higher | 0.37 | 0.028 | 0.15, 0.90 |

| Worked for wages in past 12 months (ref. No wage work) | |||

| Throughout year | 2.11 | 0.052 | 0.99, 4.50 |

| Seasonally | 0.76 | 0.283 | 0.45, 1.26 |

| Pain in past 4 weeks interfered w/work (ref. Slightly/not at all) | |||

| Quite a bit/extremely | 0.36 | <0.001 | 0.21, 0.62 |

| Moderately | 0.24 | <0.001 | 0.13, 0.43 |

| Health limited moderate activities (ref. Not limited at all) | |||

| Limited a lot | 0.47 | 0.066 | 0.21,1.05 |

| Limited a little | 0.41 | <0.001 | 0.27, 0.63 |

| Has energy in past 4 weeks (ref. A good bit /all of the time) | |||

| None of the time/a little of the time | 0.99 | 0.970 | 0.59, 1.65 |

| Some of the time | 0.68 | 0.123 | 0.42, 1.10 |

| Felt downhearted and blue in past 4 weeks (ref. None of time/a little of time) | |||

| A good bit of time/all of time | 0.54 | 0.009 | 0.34, 0.86 |

| Some of time | 0.70 | 0.172 | 0.41, 1.17 |

| Physical/emotional health interfered with social activities (ref. None of time/a little of time) | |||

| A good bit of time/all of time | 0.60 | 0.071 | 0.35, 1.05 |

| Some of time | 0.83 | 0.588 | 0.43, 1.61 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barchi, F.; AbiNader, M.A.; Winter, S.C.; Obara, L.M.; Mbogo, D.; Thomas, B.M.; Ammerman, B. “It Is Like Medicine”: Using Sports to Promote Adult Women’s Health in Rural Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2347. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18052347

Barchi F, AbiNader MA, Winter SC, Obara LM, Mbogo D, Thomas BM, Ammerman B. “It Is Like Medicine”: Using Sports to Promote Adult Women’s Health in Rural Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2347. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18052347

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarchi, Francis, Millan A. AbiNader, Samantha C. Winter, Lena M. Obara, Daniel Mbogo, Bendettah M. Thomas, and Brittany Ammerman. 2021. "“It Is Like Medicine”: Using Sports to Promote Adult Women’s Health in Rural Kenya" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2347. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph18052347