The Centre for Healthy Weights—Shapedown BC: A Family-Centered, Multidisciplinary Program that Reduces Weight Gain in Obese Children over the Short-Term

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. The Program

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

| Assessment | Time Point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intake | Baseline (Week 1) | Weeks 2–9 | Program completion (Week 10) | ||

| Social Demographic Information | Date of Birth | ✓ | |||

| Sex | ✓ | ||||

| Ethnicity | ✓ | ||||

| Anthropometric Measurements | Waist Circumference | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Weight | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Height | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Blood Pressure | ✓ | ||||

| Metabolic Profile | Fasting Glucose | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Fasting Insulin | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Fasting Lipid Panel * | ✓ | ||||

| Physical Activity Assessment | Physical Activity Questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Psychological Parameters | Child Behaviour Checklist | ✓ | |||

| Beck Youth Inventory | ✓ | ✓ | |||

2.4.1. Anthropometric Measurements

2.4.2. Metabolic Profile

2.4.3. Physical Activity Assessment

2.4.4. Psychological Parameters

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

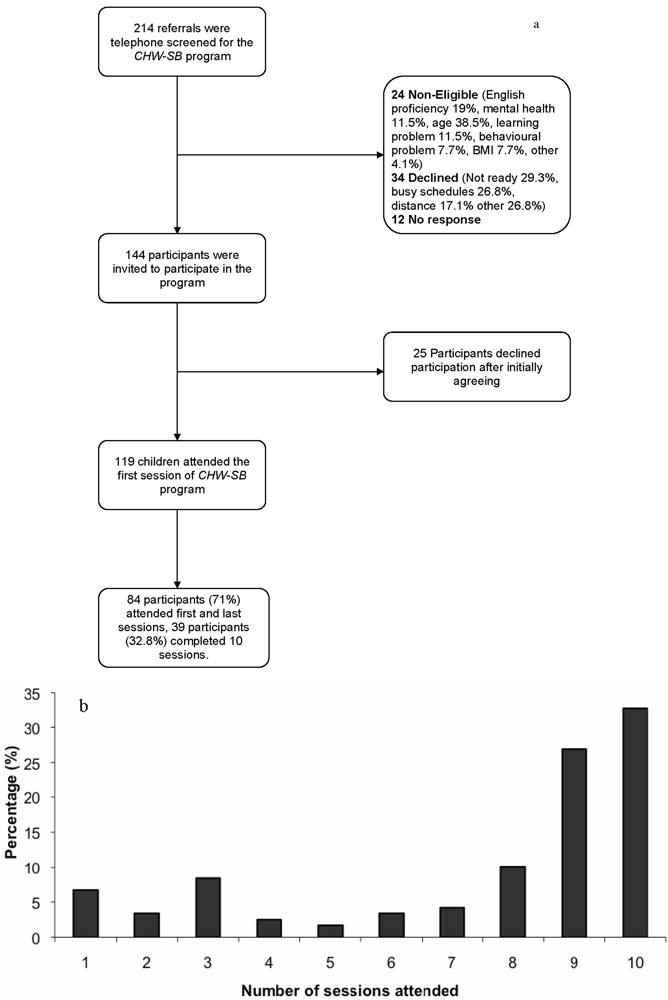

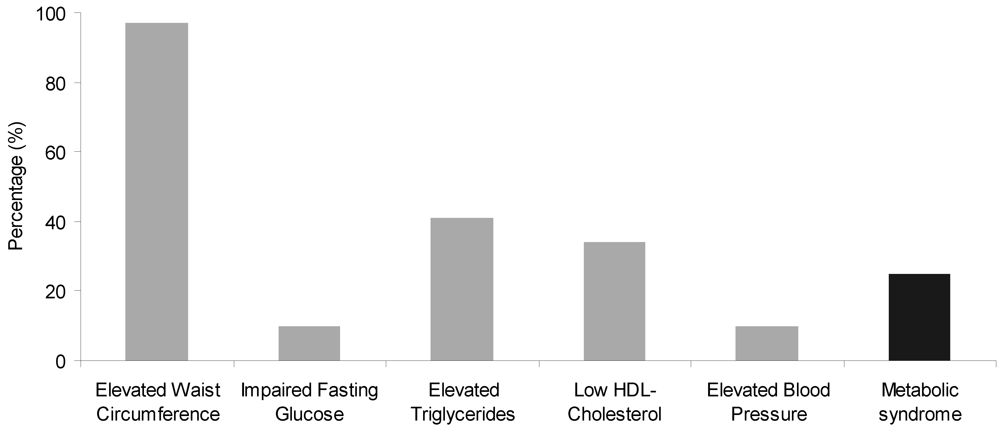

3.1. Study Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | CHW-SB participants N = 119 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 11.6 ± 2.6 | ||

| Male sex (%) | 57 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 76.7 ± 26.8 | ||

| Height (cm) | 154.5 ± 14.7 | ||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 30.9 ± 6.20 | ||

| BMI z-score | 2.3 ± 0.33 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 98.5 ± 15.70 | ||

| Ethnicity: (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 55.6 | ||

| Asian | 17.6 | ||

| Indian/Pakistani | 13.4 | ||

| Arab | 4.2 | ||

| African American | 1.7 | ||

| South American | 0.8 | ||

| First Nations | 0.8 | ||

| Other * | 5.9 | ||

| Child Behavior Checklist | Normal | Borderline | Clinical |

| Internalizing Problems (%) | 41.8 | 9.1 | 49.1 |

| Externalizing Problems (%) | 69.1 | 11.8 | 19.1 |

3.2. Change in Weight Trajectory

= Non-parametric smooth of the data points;

= Non-parametric smooth of the data points;  = Overall prediction line from the mixed model effect; Normalized weight = log(weight); Phase 1: Intake to program baseline; Phase 2: Baseline to program evaluation.

= Overall prediction line from the mixed model effect; Normalized weight = log(weight); Phase 1: Intake to program baseline; Phase 2: Baseline to program evaluation.

= Non-parametric smooth of the data points;

= Non-parametric smooth of the data points;  = Overall prediction line from the mixed model effect; Normalized weight = log(weight); Phase 1: Intake to program baseline; Phase 2: Baseline to program evaluation.

= Overall prediction line from the mixed model effect; Normalized weight = log(weight); Phase 1: Intake to program baseline; Phase 2: Baseline to program evaluation.

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

| Baseline | Evaluation | Difference | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise (min) | 309 ± 267 | 461 ± 425 | 152 ± 412 | 0.001 |

| Exercise (MET min) | 1955 ± 1748 | 2942 ± 2675 | 986 ± 2538 | 0.001 |

| All Moderate PA (min) | 402 ± 285 | 593 ± 500 | 191 ± 486 | 0.001 |

| All Moderate PA (MET min) | 2397 ± 1786 | 3539 ± 2890 | 1142 ± 2734 | 0.000 |

| Total physical inactivity (min) | 860 ± 663 | 530 ± 486 | −330 ± 575 | 0.000 |

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Disclosure statement

References

- Lobstein, T.; Frelut, M.L. Prevalence of overweight among children in Europe. Obes. Rev. 2003, 4, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hedley, A.A.; Ogden, C.L.; Johnson, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Curtin, L.R.; Flegal, K.M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2004, 291, 2847–2850. [Google Scholar]

- Lissau, I.; Overpeck, M.D.; Ruan, W.J.; Due, P.; Holstein, B.E.; Hediger, M.L.; Health behaviour in school-aged children obesity working group. Body mass index and overweight in adolescents in 13 European countries, Israel, and the United States. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shields, M. Overweight and obesity among children and youth. Health Rep. 2006, 17, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Willms, J.D. Secular trends in the body mass index of Canadian children. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2000, 163, 1429–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, P. Fat babies and fat children. The prognosis of obesity in the very young. Arch. Dis. Child. 1966, 41, 672–673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nader, P.R.; O’Brien, M.; Houts, R.; Bradley, R.; Belsky, J.; Crosnoe, R.; Friedman, S.; Mei, Z.; Susman, E.J. National institute of child health and human development early child care research network. Identifying risk for obesity in early childhood. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e594–e601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salsberry, P.J.; Reagan, P.B. Dynamics of early childhood overweight. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, R.C.; Wright, J.A.; Pepe, M.S.; Seidel, K.D.; Dietz, W.H. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 869–873. [Google Scholar]

- Power, C.; Lake, J.K.; Cole, T.J. Measurement and long-term health risks of child and adolescent fatness. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1997, 21, 507–526. [Google Scholar]

- Cornier, M.A.; Dabelea, D.; Hernandez, T.L.; Lindstrom, R.C.; Steig, A.J.; Stob, N.R.; van Pelt, R.E.; Wang, H.; Eckel, R.H. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 777–822. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, E.S.; Giles, W.H.; Dietz, W.H. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: Findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 287, 356–359. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, S.; Weitzman, M.; Auinger, P.; Nguyen, M.; Dietz, W.H. Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: Findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1994. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2003, 157, 821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Berenson, G.S.; Srinivasan, S.R.; Bao, W.; Newman, W.P., III; Tracy, R.E.; Wattigney, W.A. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. The Bogalusa heart study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 1650–1656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, C.; Williams, K.; Hunt, K.J.; Haffner, S.M. The national cholesterol education program—Adult treatment panel III, international diabetes federation, and world health organization definitions of the metabolic syndrome as predictors of incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, P.W.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Parise, H.; Sullivan, L.; Meigs, J.B. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2005, 112, 3066–3072. [Google Scholar]

- De Ferranti, S.D.; Gauvreau, K.; Ludwig, D.S.; Neufeld, E.J.; Newburger, J.W.; Rifai, N. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in American adolescents: Findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Circulation 2004, 110, 2494–2497. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, H.E.; Jones, K.; Ruotolo, G.; Jain, A.K.; Henderson, J.; Lu, W.; Howard, B.V.; Strong Heart Study. Insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic American Indians: The strong heart study. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buddeberg-Fischer, B.; Klaghofer, R.; Reed, V. Associations between body weight, psychiatric disorders and body image in female adolescents. Psychother. Psychosom. 1999, 68, 325–332. [Google Scholar]

- Britz, B.; Siegfried, W.; Ziegler, A.; Lamertz, C.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.M.; Remschmidt, H.; Wittchen, H.U.; Hebebrand, J. Rates of psychiatric disorders in a clinical study group of adolescents with extreme obesity and in obese adolescents ascertained via a population based study. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2000, 24, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, W.H.; Robinson, T.N. Use of the body mass index (BMI) as a measure of overweight in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. 1998, 132, 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- Puhl, R.M.; Latner, J.D. Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation’s children. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 557–580. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Wake, M.; Hesketh, K.; Maher, E.; Waters, E. Health-related quality of life of overweight and obese children. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005, 293, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, D.C.; Douketis, J.D.; Morrison, K.M.; Hramiak, I.M.; Sharma, A.M.; Ur, E.; Obesity Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Panel. 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2007, 176, S1–S13. [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley, D.E.; Tibbs, T.L.; Van Buren, D.J.; Reach, K.P.; Walker, M.S.; Epstein, L.H. Lifestyle interventions in the treatment of childhood overweight: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 521–532. [Google Scholar]

- Summerbell, C.D.; Ashton, V.; Campbell, K.J.; Edmunds, L.; Kelly, S.; Waters, E. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003, CD001872. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, E.L.; Glenny, A.M.; Kirk, S.F.; Summerbell, C.D. An updated systematic review of interventions to improve health professionals’ management of obesity. Obes. Rev. 2002, 3, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Oude Luttikhuis, H.; Baur, L.; Jansen, H.; Shrewsbury, V.A.; O’Malley, C.; Stolk, R.P.; Summerbell, C.D. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Mellin, L.M.; Slinkard, L.A.; Irwin, C.E., Jr. Adolescent obesity intervention: Validation of the SHAPEDOWN program. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1987, 87, 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Dobersen, D.A.; Butler-Simon, N.; Fleshner, M. Evaluation of a weight management intervention program in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1993, 93, 535–540. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Children’s Hospital. Centre for Healthy Weights—BC; British Columbia Children’s Hospital: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2009. Available online: http://bit.ly/centreforhealthyweights (accessed on 11 November 2011).

- Health Canada. Canada’s Food Guide; Health Canada: Ottawa, Canada, 2011. Available online: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/index-eng.php (accessed on 11 November 2011).

- Barlow, S.E. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary report. Pediatrics 2007, 120, S164–S192. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Guo, S.S.; Wei, R.; Mei, Z.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. CDC Growth Charts: United States. Adv. Data 2000, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, H.D.; Jarrett, K.V.; Crawley, H.F. The development of waist circumference percentiles in British children aged 5.0-16.9 y. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 902–907. [Google Scholar]

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2004, 114, 555–576.

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, J.R.; Redden, D.T.; Pietrobelli, A.; Allison, D.B. Waist circumference percentiles in nationally representative samples of African-American, European-American, and Mexican-American children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2004, 145, 439–444. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, S42–S47.

- Crocker, P.R.; Bailey, D.A.; Faulkner, R.A.; Kowalski, K.C.; McGrath, R. Measuring general levels of physical activity: Preliminary evidence for the physical activity questionnaire for older children. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1997, 29, 1344–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, K.C.; Crocker, P.R.; Faulkner, R.A. Validation of the physical activity questionnaire for older children. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 1997, 9, 174–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, K.C.; Crocker, P.R.; Kowalski, N.P. Convergent validity of the physical activity questionnaire for adolescents. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 1997, 9, 342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Leon, A.S.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Montoye, H.J.; Sallis, J.F.; Paffenbarger, R.S., Jr. Compendium of physical activities: Classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescoria, L.A. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles; Research Center for Children, Youth & Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Edelbrock, C.S. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile; University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry: Burlington, VT, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J.S.; Beck, A.T.; Jolly, J.B.; Steer, R.A. Clinical Application and Interpretation. In Manual for Beck Youth Inventories Second Edition for Children and Adolescents; Pearson Inc: TX, USA, 2005; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, N.M.; Ware, J.H. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 1982, 38, 963–974. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, R.; Taksali, S.E.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Burgert, T.S.; Savoye, M.; Caprio, S. Predictors of changes in glucose tolerance status in obese youth. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 902–909. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, G.D.; Ambler, K.A.; Chanoine, J.P. Pediatric weight management programs in Canada: Where, what and how? Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, e58–e61. [Google Scholar]

- Dreimane, D.; Safani, D.; MacKenzie, M.; Halvorson, M.; Braun, S.; Conrad, B.; Kaufman, F. Feasibility of a hospital-based, family-centered intervention to reduce weight gain in overweight children and adolescents. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007, 75, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Savoye, M.; Shaw, M.; Dziura, J.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Rose, P.; Guandalini, C.; Goldberg-Gell, R.; Burgert, T.S.; Cali, A.M.; Weiss, R.; et al. Effects of a weight management program on body composition and metabolic parameters in overweight children: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 297, 2697–2704. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.K.; Franco, R.L.; Stern, M.; Wickham, E.P.; Bryan, D.L.; Herrick, J.E.; Larson, N.Y.; Abell, A.M.; Laver, J.H. Evaluation of a 6-month multi-disciplinary healthy weight management program targeting urban, overweight adolescents: Effects on physical fitness, physical activity, and blood lipid profiles. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2009, 4, 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Vignolo, M.; Rossi, F.; Bardazza, G.; Pistorio, A.; Parodi, A.; Spigno, S.; Torrisi, C.; Gremmo, M.; Veneselli, E.; Aicardi, G. Five-year follow-up of a cognitive-behavioural lifestyle multidisciplinary programme for childhood obesity outpatient treatment. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T.L.; Letuchy, E.M.; Paulos, R.; Witt, J. Childhood predictors of the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults: The muscatine study. J. Pediatr. 2009, 155, e17–e26. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.A.; Bremer, A.A. Insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in the pediatric population. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2010, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, O.H.; Massaro, J.M.; Civil, J.; Cobain, M.R.; O’Malley, B.; D’Agostino, R.B., Sr. Trajectories of entering the metabolic syndrome: The framingham heart study. Circulation 2009, 120, 1943–1950. [Google Scholar]

- Zeller, M.H.; Saelens, B.E.; Roehrig, H.; Kirk, S.; Daniels, S.R. Psychological adjustment of obese youth presenting for weight management treatment. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 1576–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, G.; Zipper, E.; Dabbas, M.; Bertrand, C.; Robert, J.J.; Ricour, C.; Mouren-Simeoni, M.C. Mental disorders in obese children and adolescents. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng, J.C.; Gannon, K.; Cabral, H.J.; Frank, D.A.; Zuckerman, B. Association between clinically meaningful behavior problems and overweight in children. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Panagiotopoulos, C.; Ronsley, R.; Al-Dubayee, M.; Brant, R.; Kuzeljevic, B.; Rurak, E.; Cristall, A.; Marks, G.; Sneddon, P.; Hinchliffe, M.; et al. The Centre for Healthy Weights—Shapedown BC: A Family-Centered, Multidisciplinary Program that Reduces Weight Gain in Obese Children over the Short-Term. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 4662-4678. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph8124662

Panagiotopoulos C, Ronsley R, Al-Dubayee M, Brant R, Kuzeljevic B, Rurak E, Cristall A, Marks G, Sneddon P, Hinchliffe M, et al. The Centre for Healthy Weights—Shapedown BC: A Family-Centered, Multidisciplinary Program that Reduces Weight Gain in Obese Children over the Short-Term. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011; 8(12):4662-4678. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph8124662

Chicago/Turabian StylePanagiotopoulos, Constadina, Rebecca Ronsley, Mohammed Al-Dubayee, Rollin Brant, Boris Kuzeljevic, Erin Rurak, Arlene Cristall, Glynis Marks, Penny Sneddon, Mary Hinchliffe, and et al. 2011. "The Centre for Healthy Weights—Shapedown BC: A Family-Centered, Multidisciplinary Program that Reduces Weight Gain in Obese Children over the Short-Term" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 8, no. 12: 4662-4678. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijerph8124662