Stakeholder Participation and Advocacy Coalitions for Making Sustainable Fiji Mineral Royalty Policy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Approach to Public Policy Process

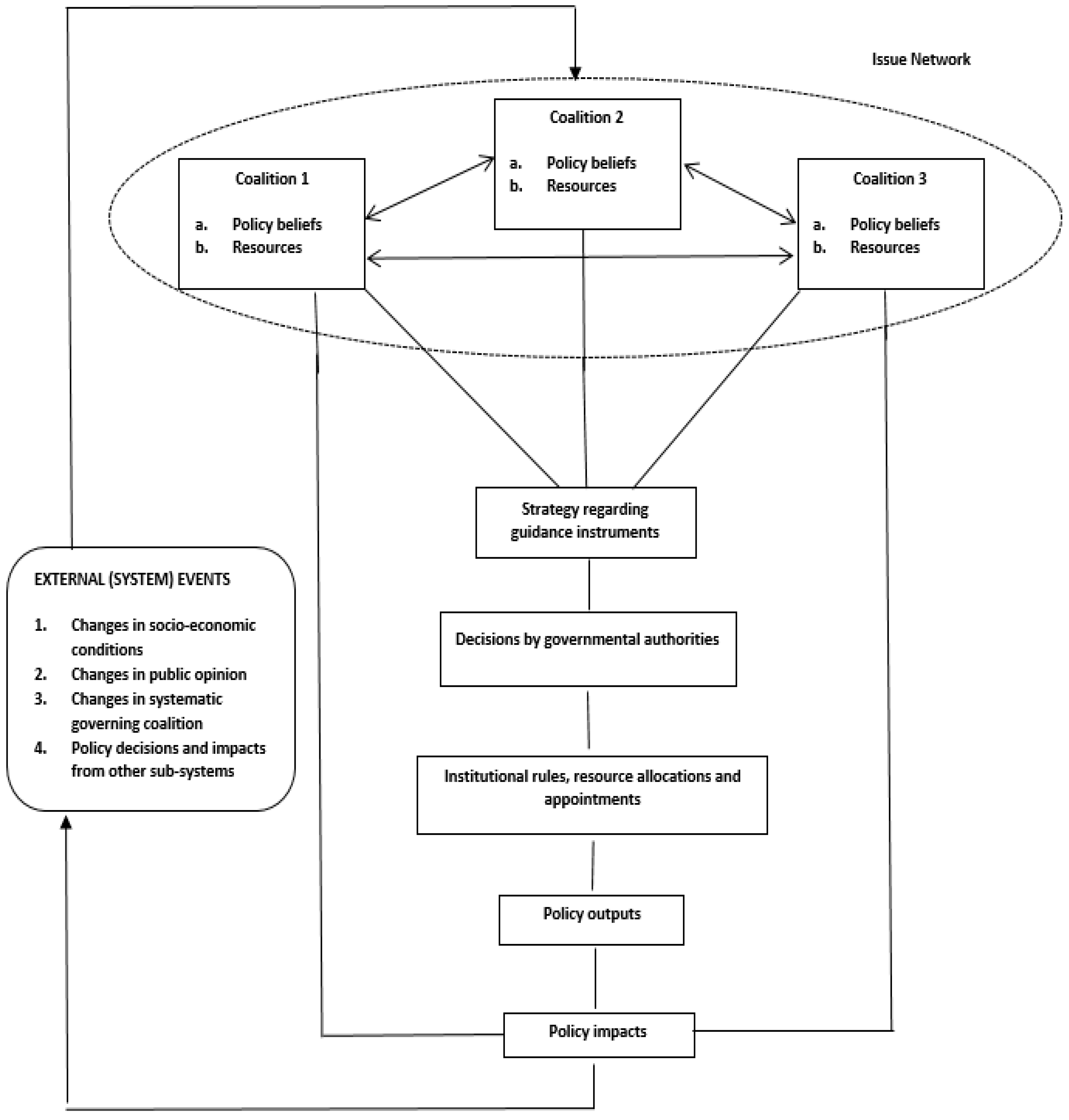

2.1. Advocacy Coalition Framework

2.2. Issue Network Theory

2.3. Synthesis of ACF and Issue Network

3. Research Design

3.1. Case Selection: Mineral Royalty Policy in Fiji

3.2. Method

4. Background

4.1. The Need for Fiji Mineral Royalty Policy

4.2. The Coup Culture in Fiji

5. Competing Policy Beliefs and Values among the Advocacy Coalitions

5.1. The Advocacy Coalitions’ Beliefs, Strategies and Powers

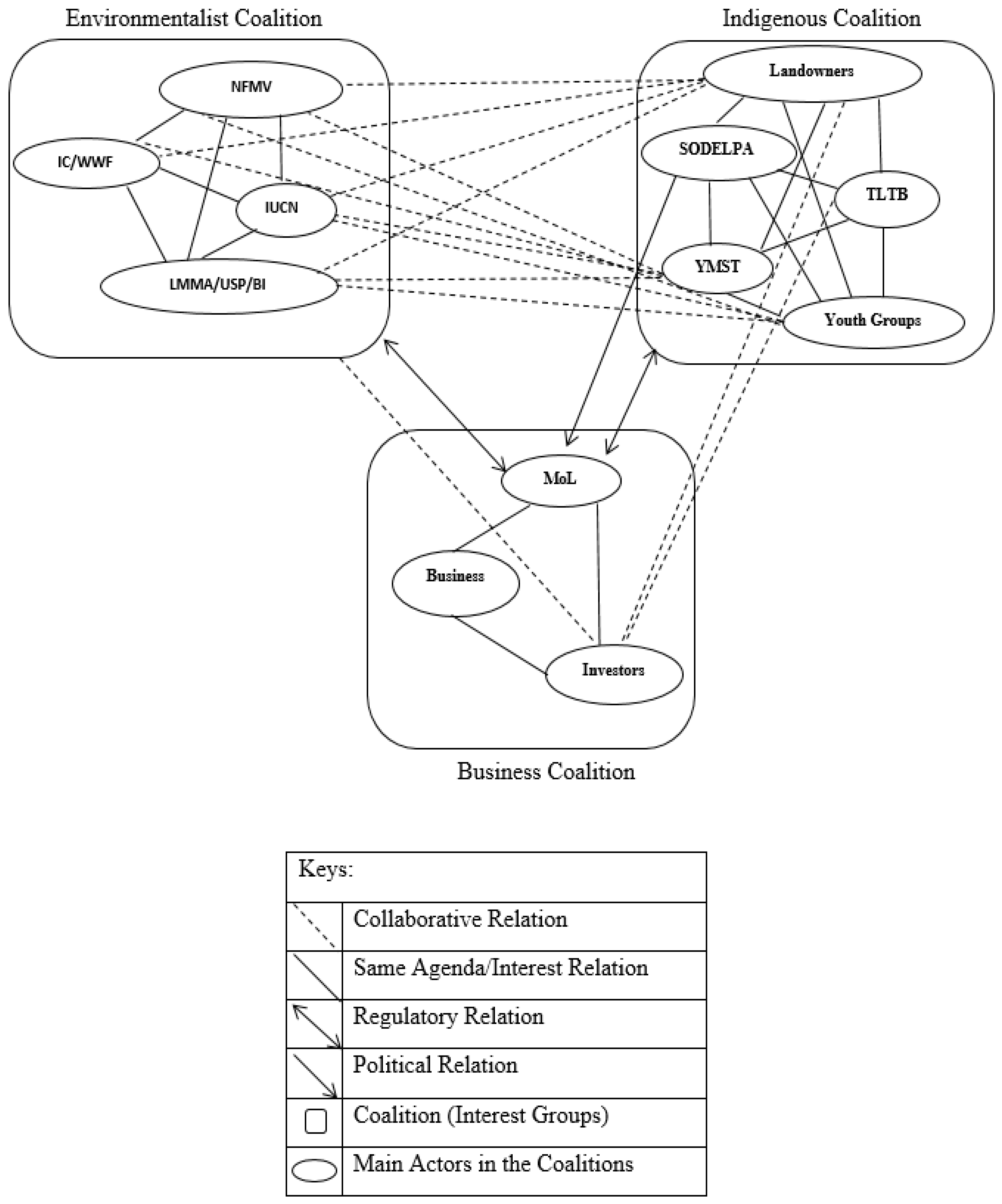

5.2. Advocacy Coalitions Composition

5.2.1. Indigenous Coalition

5.2.2. Environmentalist Coalition

5.2.3. Business Coalition

5.3. Resource Dependencies among Advocacy Coalitions in Agenda Setting

6. Dynamics in Interactions within Each Coalition and among Coalitions in FMRP

6.1. Indigenous Coalition’s Interactions and Networks

6.2. Environmentalists Coalition’s Interactions and Networks

6.3. Business Coalition’s Interactions and Networks

7. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Decree Amendments | Descriptions |

| 1 | Fijian Affairs Great Council of Chiefs Regulation of 2007 | Suspended the role of the Great Council of Chiefs (GCC). |

| 2 | Fijian Affairs Great Council of Chiefs Regulation of 2008 | Eliminates nomination of GCC members from the ‘iTaukeis.’ |

| 3 | Fijian Affairs Provincial Council Amendment Regulation 2008 | Government appoints Fijian Affairs Board and Provincial Councils members. |

| 4 | Native Land Trust Amendment Decree No. 39 of 2009 | Government chooses iTaukei Land Trust Board (TLTB) members. |

| 5 | Native Land Trust Regulation Amendment of 2010 | Equal distribution of lease money. |

| 6 | Mahogany Industry Development Decree No. 16 of 2010 | TLTB are not responsible for administering mahogany leases. A separate entity has been established. |

| 7 | Regulation of Surfing Area Decree No. 35 of 2010 | ‘iTaukeis’ are deprived of ‘qoliqoli’ (fishing) rights and government can endorse tourism initiatives (hotel/surfing) without consulting ‘qoliqoli’ owners. |

| 8 | Fijian Affairs Amendment Decree No.31 of 2010 | Change of Fijians to iTaukei for native Fijians. All citizens are called Fijians. |

| 9 | Native Land Trust Amendment Decree No. 32 of 2010 | The Prime Minister of the Government is the president and chairs the TLTB and also appoints Board members. Normally is was the President who appointed the president, the chairperson and the ‘iTaukeis’ who appointed Board members. |

| 10 | Native Land Trust Amendment Decree No. 20 of 2010 | All extinct land belongs to the government. |

| 11 | Native Land Trust Amendment Decree of 2012 | All extinct land belongs to the government. Previously, the GCC controls extinct lands. |

| 12 | iTaukei Affairs Amendment Decree No. 22 of 2012 | Dissolvement of GCC. |

| 13 | Constitution of the Republic of Fiji 2013 | Government weakens the landownership for ‘iTaukeis.’ |

| (Source: [41]). | ||

References

- Otto, J.; Andrews, C.; Cawood, F.; Doggett, M.; Guj, P.; Stermole, F.; Stermole, J.; Tilton, J. Mining Royalties: A Global Study of Their Impact on Investors, Government, and Civil Society; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Portz, J. Problem Definitions and Policy Agendas: Shaping the Educational Agenda in Boston. Policies Stud. J. 1996, 24, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Berry, F.S.; Lee, K.-H. Stakeholders in the Same Bed with Different Dreams: Semantic Network Analysis of Issue Interpretation in Risk Policy Related to Mad Cow Disease. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J.; Peterso, N. A Case for Retaining Aboriginal Mining Veto and Royalty Rights in the Northern Territory. Aust. Aborig. Stud. 1984, 2, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, T. Importance of Mineral Rights and Royalty Interests for Rural Residents and Landowners. Choices 2014, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- O’Faircheallaigh, C. Indigenous People and Mineral Taxation Regimes. Resour. Policy 1998, 24, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Faircheallaign, C. Denying Citizens Their Rights?: Indigenous People, Mining Payments and Service Provision. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2004, 63, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.A. An Advocacy Coalition Framework of Policy Change and the Role of Policy-oriented Learning Therein. Policy Sci. 1988, 21, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, R.; Peterse, A. Handling Frozen Fire; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, P. Understanding Public Policy: Theories and Issues; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A.; Weible, C. The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Innovations and Clarifications, Theories of the Policy Process. In Theories of the Policy Process, 2nd ed.; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A. The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Revisions and Relevance for Europe. J. Eur. Public Policy 1998, 5, 98–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, C.; Schlaepfer, R. Understanding Forest Certification Using Advocacy Coalition Framework. For. Policy Econ. 2001, 2, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heclo, H. Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment: The New American Political System; American Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gormley, W.T. Regulatory Issue Networks in a Federal System. Polity 1986, 18, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkland, T.A. An Introduction to the Policy Process: Theories, Concepts and Models of Public Policy Making, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Waarden, F.V. Dimensions and Types of Policy Networks. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 1992, 21, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knocke, D. Political Networks: The Structural Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A. (Ed.) Theories of the Policy Process; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Committee on Natural Resources Report. Petition on the Mining of Bauxite Final Report; Parliament of the Republic of Fiji: Suva, Fiji, 2015.

- Xun, S. 2017 Minerals Yearbook-Fiji; USGS-Science for Changing World; The Mineral Industry of Fiji: Suva, Fiji, 2017; pp. 1–3.

- Shi, L. 2013 Minerals Yearbook-Fiji; USGS-Science for Changing World; The Mineral Industry of Fiji: Suva, Fiji, 2013; pp. 1–4.

- Namosi Joint Venture. Bula Vinaka Welcome to Namosi Joint Venture. 2016. Available online: http://www.njv.com.fj/about-us/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Harrinkari, T.; Katila, P.; Karppinen, H. Stakeholder Coalitions in Forest Politics: Revision of Finnish Forest Act. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 67, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, E.D. The Politics of Implementing Philippine Tourism Policy: A Policy Network and Advocacy Coalition Framework Approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W.; Wicki, B. What Passes as a Rigorous Case Study? Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. 2014 Minerals Yearbook-Fiji; USGS-Science for Changing World; The Mineral Industry of Fiji: Suva, Fiji, 2014; pp. 1–3.

- Ministry of Lands. More Minerals: New Findings Pose More Interest for Foreign Investors. Ministry of Lands Bulletin 2015; pp. 1–3. Available online: http://www.lands.gov.fj/images/pdf/Moremineraldepositsfound.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2018).

- McLeod, H. Compensation for Landowners Affected by Mineral Development: Fiji Experience. Resour. Policy 2000, 26, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, S. Royalties Set for Future: Vuniwaqa. Fiji Sun 2016, 5, 2287–2294. [Google Scholar]

- Fiji TV. Landowners Royalties from Mineral Extraction to be Finalised. 2014. Available online: http://fijione.tv/landowner-royalties-from-mineral-extraction-to-be-finalised/ (accessed on 29 March 2018).

- Gillion, K.L. A History of Indian Immigration and Settlement in Fiji. Master’s Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Fiji Bureau of Statistics. Statistics: Population Censuses and Survey. 2007. Available online: http://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/statistics/population-censuses-and-surveys (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Woods, B.A. The Causes of Fiji’s 5 December 2006 Coup. Master’s Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alley, R. Fiji’s Coup of 1987 and 2000: A Comparison. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 2001, 35, 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- The Fiji Government. Right to Equity and Freedom from Discrimination: Section 26. In Constitution of the Republic of Fiji; Government Printing Press: Suva, Fiji, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Toga, E. The Role of the GCC. The Fiji Times, 15 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, B. Fiji and the Coup Syndrome. Commonw. J. Int. Aff. 2012, 101, 489–601. [Google Scholar]

- Fiji Village News. Provincial Council Chairpersons to be Appointed by Government. 2012. Available online: http://fijivillage.com/news/Provincial-council-chairpersons-to-be-appointed-by-govt-rs29k5/ (accessed on 25 February 2018).

- Buadromo, J. Na Butakoci ni Dodonu ni Kawa iTaukei: Niko Matawalu. 2017. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/joe.buadromo.1/videos/1909823965950158/ (accessed on 16 November 2017).

- Public Accounts Committee. Report on the 5th Westminster Workshop of Public Accounts Committee; Parliament of the Republic of Fiji: Suva, Fiji, 2015.

- United States Department of State. Fiji 2016 Human Rights Reports. 2016. Available online: https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/265548.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2018).

- Rokeach, M. A Theory of Organization and Change within Value-attitude Systems. J. Soc. Issues 1968, 24, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of iTaukei Affairs. iTaukei Lands and Fisheries Commission. 2017. Available online: http://www.itaukeiaffairs.gov.fj/index.php/divisions/itaukei-lands-and-fisheries-commission (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- iTaukei Land Trust Board. Lease Types for Leasing. 2014. Available online: http://www.tltb.com.fj/ (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Laws of Fiji. Political Parties’ Registration Conduct Funding and Disclosure Act 2013; Government Printing Press: Suva, Fiji, 2013.

- Bua Provincial Council. Environment and Conservation: Yaubula Management Support Team. 2015. Available online: http://buaprovincial.com.fj/environment-and-conservation/bymst-provincial-yaubula. support-team/ (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Silaitoga, S. Bua Youths Concerned over Development Issues. The Fiji Times, 28 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Fiji Government. Rights of Ownership and Protection of iTaukei, Rotuman and Banaban lands: Section 28. In Constitution of the Republic of Fiji; Government Printing Press: Suva, Fiji, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Fiji Government. Freedom from Compulsory or Arbitrary Acquisition of Property: Section 27. In Constitution of the Republic of Fiji; Government Printing Press: Suva, Fiji, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fiji Environmental Law Association. What We Do. 2017. Available online: https://www.fela.org.fj/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- International Union of Conservation of Nature About. 2018. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/about (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- World Wildlife Fund. What We Do. South Pacific. 2017. Available online: http://www.wwfpacific.org/what_we_do/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Conservation International Fiji. Our Work: Conserving Fiji’s Watersheds, Forests, and Fisheries for Communities. 2017. Available online: http://www.conservation.org/where/Pages/Fiji.aspx (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- NatureFiji-MareqetiViti. Our Mission. 2017. Available online: https://naturefiji.org/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- BirdLife International. About BirdLife International: Who Is BirdLife International? 2018. Available online: http://www.birdlife.org/worldwide/partnership/about-birdlife (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Fiji Locally Managed Marine Protected Area Network. Fiji LMMA Network Provides Groundwork for BIOPAMA to Engage New Cadre of Conservation Officers in Fiji. 2016. Available online: http://lmmanetwork.org/fiji-lmma-network-provides-groundwork-for-biopama-to-engage-new-cadre-of-conservation-officers-in-fiji/ (accessed on 10 February 2018).

- Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources. Department of Lands Has Six Major Functions. 2017. Available online: http://www.lands.gov.fj/index.php/department-6/functions (accessed on 24 February 2018).

- Investment Fiji. Role of Investment Fiji. 2017. Available online: http://www.investmentfiji.org.fj/pages.cfm/ftiborgfj/about-ftib/role-of-ftib.html. (accessed on 24 February 2018).

- Namosi Joint Venture. Community Programmes. 2016. Available online: http://www.njv.com.fj/community/ (accessed on 9 February 2018).

- Cobb, M.H.; Ross, R.W. Cultural Strategies of Agenda Denial; University of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Birkland, T.A. After Disaster: Agenda Setting, Public Policy and Focusing Events; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rochefort, D.A.; Cobb, R.W. The Politics of Problem Definition; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, J.A. The Powers of Problem Definition: The Case of Government Paperwork. Policy Sci. 1989, 22, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, R.B. (Ed.) The Power of Public Ideas; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, M. Navigating the Seas. The Fiji Times, 18 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Satakala, M. Nacewa Heads for New York. Fiji Sun, 18 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Union of Conservation of Nature. BIOPAMA to Engage New Cadre of Conservation Officers in Fiji. 2018. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/content/biopama-engage-new-cadre-conservation-officers-fiji (accessed on 10 February 2018).

- The Parliament of Fiji. Parliamentary Debates. 2017. Available online: http://www.parliament.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/WEDNESDAY-13TH-SEPTEMBER-2017.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2018).

| Features | Indigenous Coalition | Environmentalist Coalition | Business Coalistion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Members |

|

|

|

| Deep Core Beliefs |

|

|

|

| Policy Core Beliefs |

|

|

|

| Secondary Aspects Beliefs |

|

|

|

| Strategies |

|

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiolevu, V.S.; Lim, S. Stakeholder Participation and Advocacy Coalitions for Making Sustainable Fiji Mineral Royalty Policy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 797. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11030797

Qiolevu VS, Lim S. Stakeholder Participation and Advocacy Coalitions for Making Sustainable Fiji Mineral Royalty Policy. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):797. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11030797

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiolevu, Venina Sucu, and Seunghoo Lim. 2019. "Stakeholder Participation and Advocacy Coalitions for Making Sustainable Fiji Mineral Royalty Policy" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 797. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su11030797