1. Theoretical Background

Roughly speaking, globalization has led to developments in various social areas [

1]. In turn, this evolution has not only had consequences in the economic, political, or social spheres; in the educational sphere, the implementation of innovation processes in the different educational institutions has also experienced a great evolution [

2]. In order to update and offer quality and innovative training, it is necessary to abandon traditional teaching–learning approaches [

3], as well as passive training methods [

4]. For this reason, the line of action in the educational and pedagogical field must be directed towards the development of new innovative practices. This can have a positive influence on the overall development of students [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], increasing their motivation and satisfaction [

11]. However, the inclusion of these innovative practices in the teaching–learning processes requires an effort and coordination of all the players involved. This implies both teachers [

12] and those agents involved in managing educational institutions [

13]. It is essential to begin by rethinking teaching processes [

14], where information and communication technologies (ICT) facilitate the development and application of innovative teaching methods [

15,

16].

Currently, the lines of pedagogical innovation [

17,

18,

19] focus on different educational aspects, among which the so-called collaborative teaching methods receive greater attention. This educational practice has become one of the most widely used methods in the field of education [

20], since they allow a high educational potential to be achieved [

21]. Considering the needs to be worked on and the evolution of society and education, collaborative learning is a method of teaching that occurs through the interaction of two or more people [

22] who share certain resources at certain moments of their learning [

23]. It may be necessary to bring into play the different skills of the group members [

24] in order to achieve improvements in academic performance through the relationship between individuals [

25], the exchange of experiences [

26], or the change of roles among group members [

27]. It should not be forgotten that the actions of the group members affect the acquisition of the educational objectives of the other components of the group [

28]. In general terms, collaborative learning requires a group project [

29], teamwork for problem solving [

30], pedagogical debates [

31], and work teams [

32].

Some research shows that established social relationships do not appear at the time of learning but require a period of adaptation to achieve it adequately [

33]. Clearly, an updated teacher training is essential [

34] to provide pre-service teachers with the necessary didactic and methodological tools to be able to face new learning situations and assume and put into practice their life-long learning processes. In this sense, some limitations or disadvantages of this method would be the possible lack of involvement among students in the group [

35]. This aspect must be taken into account if the training process is to be successful [

36] and highly coordinated. Any didactic process always requires a previous didactic planning and a coordination of all its members to achieve the best results [

37].

Among the advantages shown by recent research is that the teaching and learning process based on collaborative learning is positively valued by students [

38,

39], improves their interactions and communications [

40,

41], promotes communication among equals, increases their attitude [

42], motivation [

43], sense of community [

44,

45], the realization of pedagogical exercises [

46], the mental situation of the student [

47], and autonomy [

48], actively involving him in his pedagogical acts to improve his interaction [

49]. Some authors indicate that this method can contribute to improve students’ behavior and attitudes, and can influence their monitoring of learning [

50,

51]. In turn, it allows the creation of monitored teaching–learning situations where group reactions, the type of adaptive regulation and behavior can be analyzed (monitoring target, valence, and phase). This method allows the creation of opportunities and limitations in the different monitoring dimensions [

28,

52,

53].

It is essential to always create a good learning environment, a social climate in the classroom that allows the student to feel at ease. Collaborative learning also contributes to regulation. Thus, the student has more tools to face the challenges of learning, participating in different didactic situations. This allows them to learn to manage their attitudes and emotions [

54]. Collaborative learning also presents enormous advantages in relation to its use with digital competence, that is, the use of educational technologies [

55]. It favors socialization and social interaction processes, the student’s satisfaction in learning acquisition, and promotes the use of innovative didactic models that confer a leading role to students. Even in learning environments where the use of Google Docs is prevalent, it is considered a good method [

56,

57,

58,

59].

On the other hand, some authors indicate that this method also favors intercultural competence by promoting collaborative learning environments with heterogeneous groups of students [

60]. Traditional teaching–learning approaches do not allow for a focus on improving certain skills in the student training process. An example derived from recent research [

61] shows that the collaborative learning allows for the articulation of the so-called buzz groups, thus improving the effectiveness of the student-centered approach. This also contributes to improving the student’s motivation by sharing their centers of interest. Innovation, the development of processes of creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving allow for the development of collaborative learning together with experiential learning [

62,

63]. Other research indicates that this method has been beneficial for improving reading comprehension. Collaborative learning allows the development of didactic strategies that have a high positive impact on students, such as the use of peer collaboration in the analysis of complex texts [

64].

In addition, it should be noted that studies indicate that the collaborative learning method favors sustainability, especially if this method is developed digitally [

65] In addition, collaborative learning, associated with specific sustainability programs such as the European Project Semester (EPS), promotes multicultural and multidisciplinary teamwork, communication, problem solving, creativity, leadership, entrepreneurship, ethical reasoning, and global contextual analysis [

66]. The collaborative learning method has been applied in the training of students of various kinds, especially students of interior design [

67], administrative studies [

68], or agro-food systems [

69], with a view to sustainable development.

2. Justification and Objectives

The innovative topic we deal with in this paper is the so-called “collaborative learning”. Current theories prove it to be successful and spread in different research areas. In fact, it has been analyzed in the documents collected in the Web of Science (WoS). That analysis has allowed us to carry out a scientific mapping. To achieve this objective, different bibliometric indicators were analyzed, as well as the study of the performance and evolution of the term. However, we have also considered other documents in the Journal Citation Reports [

70,

71,

72]. Hence, we provide updated models to contribute to the dissemination of knowledge.

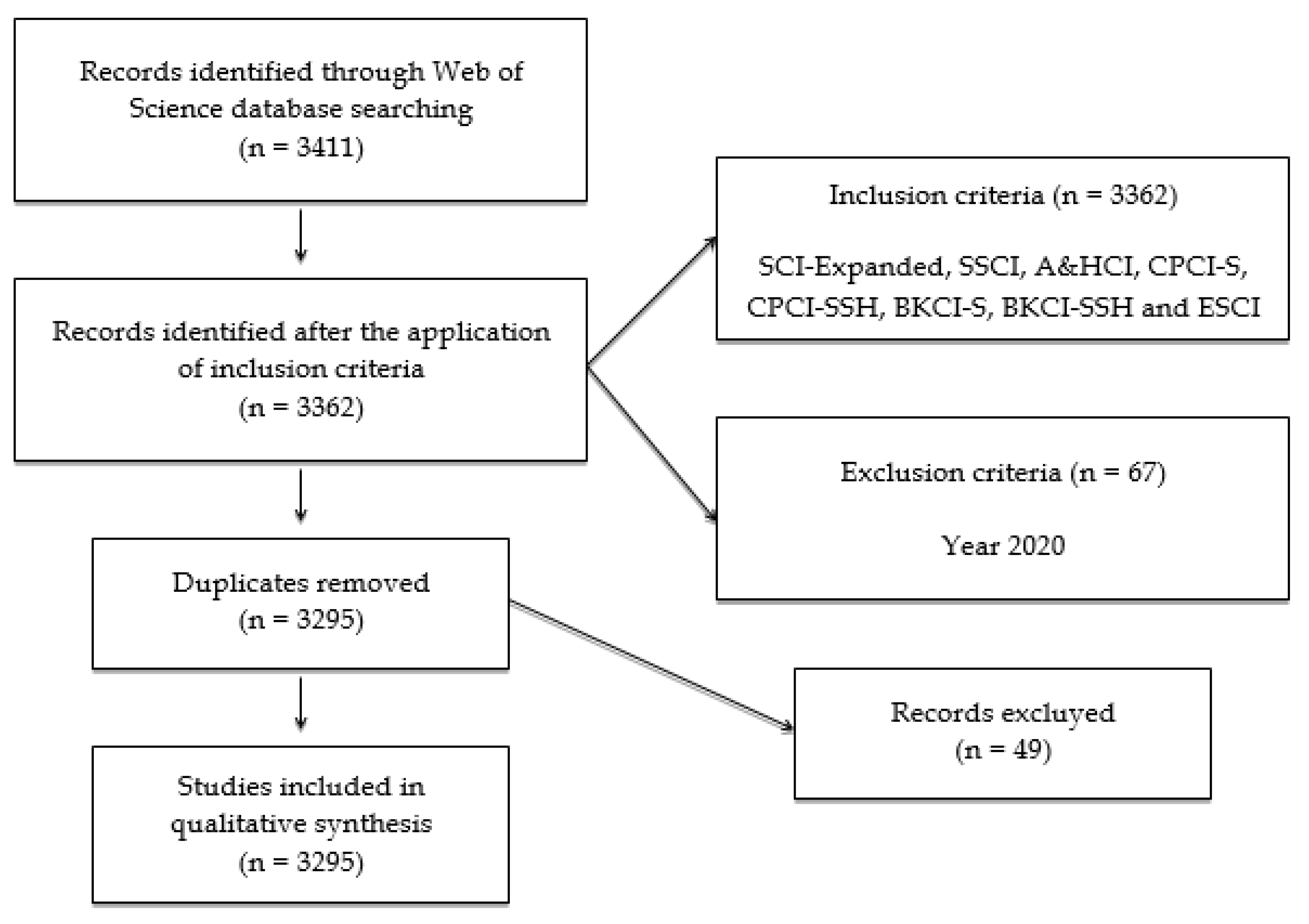

The overall objective of this study is to identify the performance and conceptual development of "collaborative learning" in the documents collected in WoS. This formulation of the objective of the research and its creation arises from the fact that there are not enough studies developed using this bibliometric technique of documentary analysis. The aim of this study is to show researchers the new findings regarding this use of the term “collaborative learning”. In this way, the knowledge researchers require in this field are covered.

Particularly, four objectives were formulated in this research: (a) To determine the degree of performance of documents collected from collaborative learning; (b) to identify the scientific development of so-called collaborative learning; (c) to analyze the most incidental aspects of collaborative learning; (d) to value the most representative authors who are experts in the use of collaborative learning.

As research questions, the following issues are established: What is the academic performance of the term collaborative learning in the scientific production of Web of Science? What is the scientific evolution and the most relevant topics in the research developed on collaborative learning in Web of Science?

5. Discussion

The new student’s profile, that is to say, a competent student, is forcing teachers to apply active teaching methods, i.e., requiring more active student’s involvement in the teaching–learning processes. In this case, teachers must become guides of this pedagogical act. The collaborative learning method is a clear example of an active teaching method [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. This teaching methodology requires two or more people who, thanks to the sharing of various resources and skills, can acquire the curricular elements proposed. This methodology encourages the development of other skills in students, such as interaction, communication, problem solving, motivation, sense of community, and autonomy, among other aspects [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. In addition, the collaborative learning method promotes and facilitates the acquisition of knowledge in areas of study where sustainable development is essential [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69].

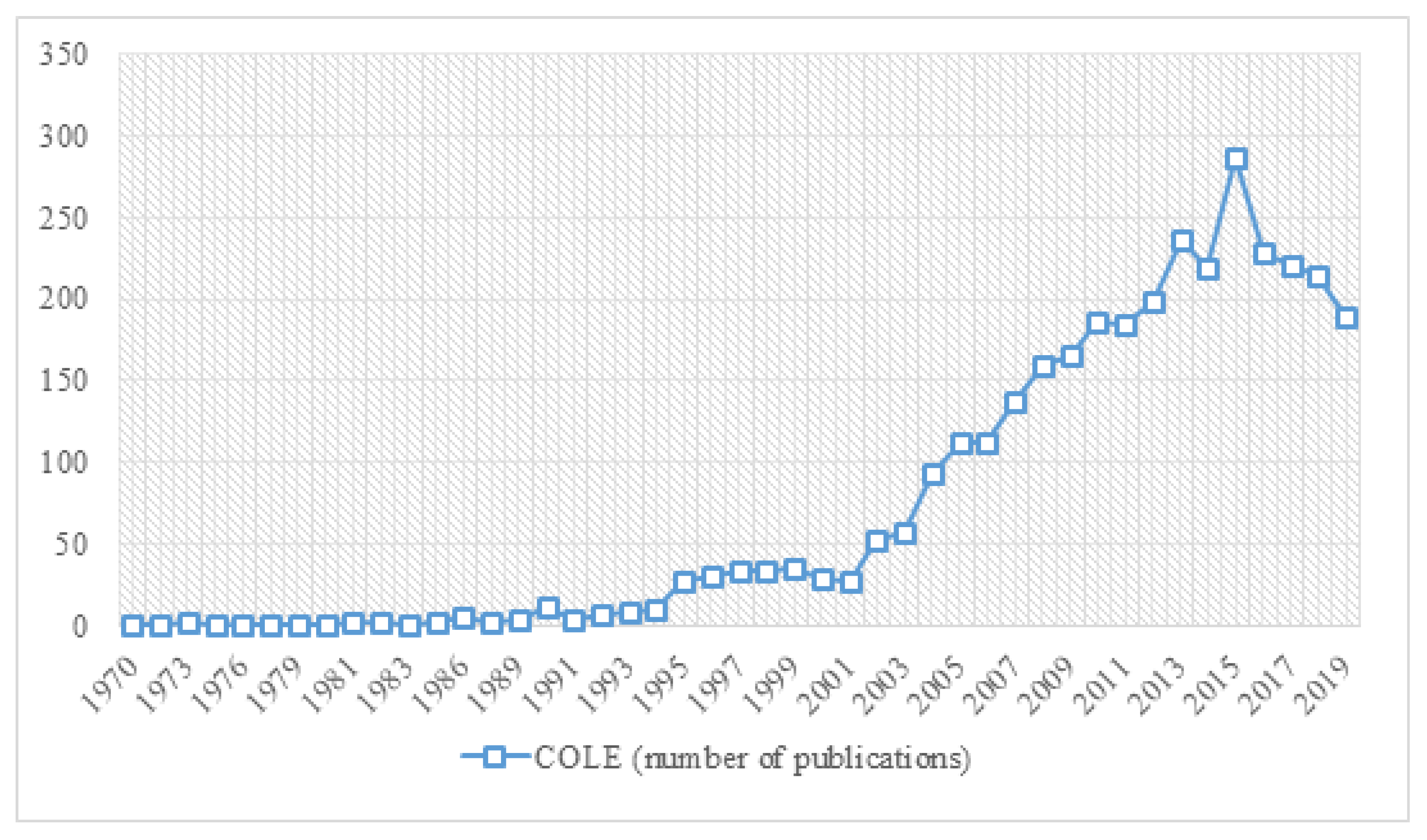

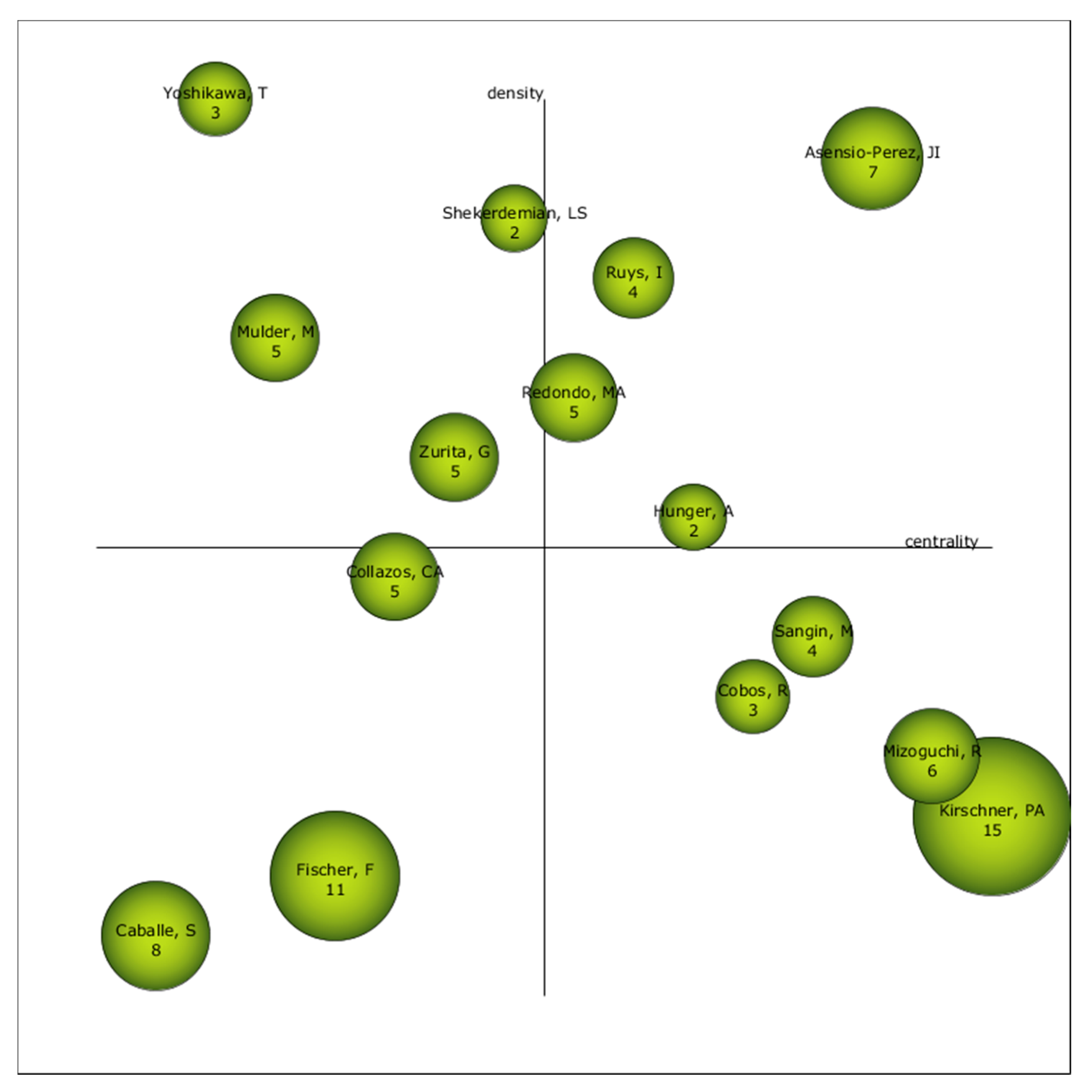

In the present study, the collaborative learning method has been analyzed in the WoS database. The beginnings of this theme in the database go back to 1970, but it is not until 2005 that scientific production begins to grow. That is to say, it is when this teaching method begins to have relevance for the scientific community, mainly due to the high pedagogical value it has. Considering the four overall research objectives, we may argue that with regards to a) degree of performance of documents collected from collaborative learning, we have conducted the present research has made it possible to establish an X-ray of the profile presented by the studies related to the collaborative learning method by the scientific community. In this case, it can be said that they are presented in articles written in English by researchers from the United States. They are gathered in the area of knowledge called Education Educational Research. The institution with the greatest scientific production is the UOC Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. The most prolific authors are Cabelle, S., and Jarvela, S., although the most relevant authors are Asensio-Pérez, J.I., Ruys, I., Redondo, M.A., and Hunger, A. The main source of production is Lectura Notes in Computer Science. The most cited article is the work of Stahl, Koschmann, and Suther (2006), called Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. These data show us that the interest in the collaborative learning method goes back several years, but it is in recent years where the interest has been growing considerably. These results may allow the scientific community to search, in a more efficient way, for studies related to collaborative learning.

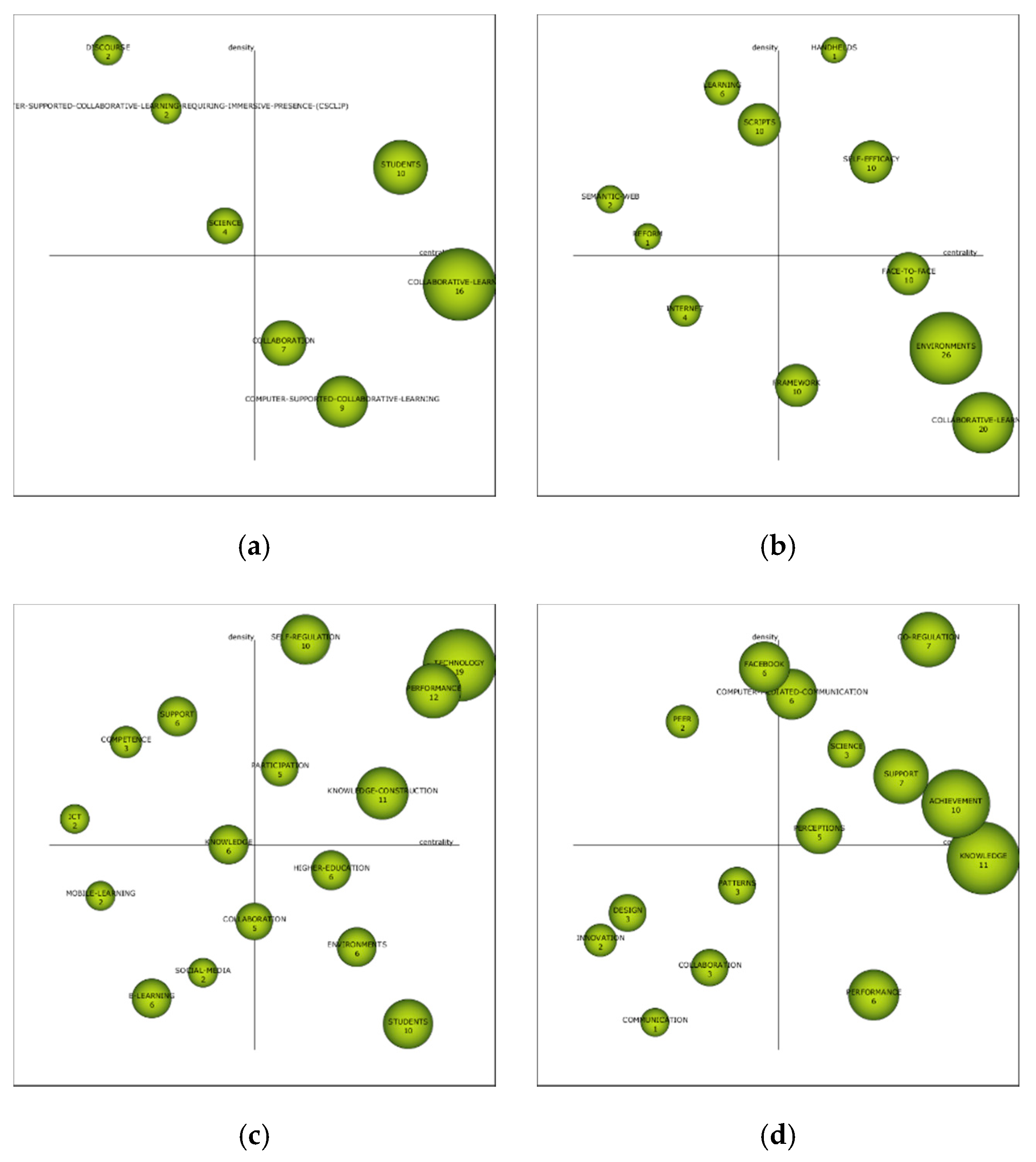

The keywords of the analyzed manuscripts show us relevant and interesting information about the subject of the collaborative learning. In this case, we can see how the evolution of keywords during the different established time periods is decreasing. That is, as the years go by, the number of coincidences between the established periods is lower. This shows that there was a line of research established in the first time intervals, but currently new research perspectives are being established.

If we consider how the scientific development of the so-called collaborative learning has been identified (second research objective), we may say that the academic performance of the topics generated from these keywords shows that there is no coincidence in any of the established periods. That is, there are no themes that are repeated in the four periods. In the first period (1970–2006), the research was focused on the method itself, that is, on the collaborative learning. In the second period (2007–2011), on the learning environments. In the third period (2012–2015), on technology. In the fourth period (2016–2019), on knowledge. In other words, there is a variety of themes, all of them oriented to learning, to the environment where it takes place and to the technological resources.

Last but not least, with regards to the analysis of the most incidental aspects of collaborative learning and the value the most representative authors who are experts in the use of collaborative learning, we may consider the diagrams established and generated in each of the periods show us the really relevant topics for the educational community. In this case, in the first period (1970–2006), it was the students. In the following time frame (2007–2011), it was the portable resources and the self-efficacy of the training process.

In the third period (2012–2015), there was a change of trend, expanding the lines of research, oriented towards the acquisition of knowledge, self-regulation, and student’s involvement in learning. In the last period (2016–2019), the focus is more on the co-regulation of learning, on the use of technological resources, and on the educational achievements of the students themselves. As it can be seen, the focus has shifted from the students themselves to the various branches of knowledge. In other words, studies are based on learning skills to develop the competence of learning to learn. All of this is associated with the use of technological resources.

Thematic developments in adjacent periods confirm the results achieved previously. In this case, no solid line of research is shown on the collaborative learning method, there being a conceptual gap in the research field. What the thematic evolution offers is the appearance of new lines of inquiry as time goes by. All these data facilitate and provide detailed information on the most relevant lines of research and trends in this field of study. With this, the scientific community, interested in studies on collaborative learning, will know, in a more concise way, the most interesting aspects for the scientific community. It will identify the topics of study most analyzed by the researchers. In addition, it provides a clear and concise image of all the lines of study established in the various years. In doing so, it offers more detail on the studies carried out in recent years.

6. Conclusions

Finally, the conclusion that can be drawn about the use of collaborative learning is somehow at a turning point in the scientific field. Its scientific evolution, focused on its principles in the students themselves, has extended to other branches. Currently, studies are oriented towards technological resources, co-regulation, and the academic achievements of students. Furthermore, in the coming years, the terms innovation, design, patterns, collaboration, and communication will probably be the new lines of research in this field of study. For this reason, the degree of performance of documents shows the relevance of collaborative learning. More precisely, this research aims to provide the scientific community with the most representative aspects of COLE studies. In addition, the aim is to offer the educational community a more in-depth knowledge of this teaching method. It also tries to offer the latest trends.

On the other hand, considering the scientific development of the collaborative learning we have shown that academic performance proofs no coincidence in any established periods. However, the analysis of the most incidental aspects of the collaborative learning lets us be aware of how authors generate knowledge based on the diagrams shown.

The prospective of this research is to provide the scientific community with updated information on the collaborative learning method. It also aims to be a reference point for teachers from different educational stages, so that they can learn about the latest trends and the different pedagogical applications of this teaching method. Finally, it was also presented to show that the collaborative learning method promotes training in students to face sustainability.

The present investigation has several limitations, including the adequacy of the database. This requires an in-depth analysis, to identify those scientific productions not related to the subject of study. In this case, the volume of production is high. Another aspect is determining the time periods. The researchers chose to follow the criterion of quantity, trying to accumulate a similar number of productions in each of the time periods. Thirdly, the indicators established in the SciMAT v.1.1.04 (2016) program are set by the authors themselves. If these values are modified, the results present in this study may change. For new lines of research in the future, we propose to identify the collaborative learning method in specific educational branches, such as Mathematics or Social Sciences. In addition, an analysis of the term collaborative learning can be carried out in other databases, such as Scopus or Google Scholar.