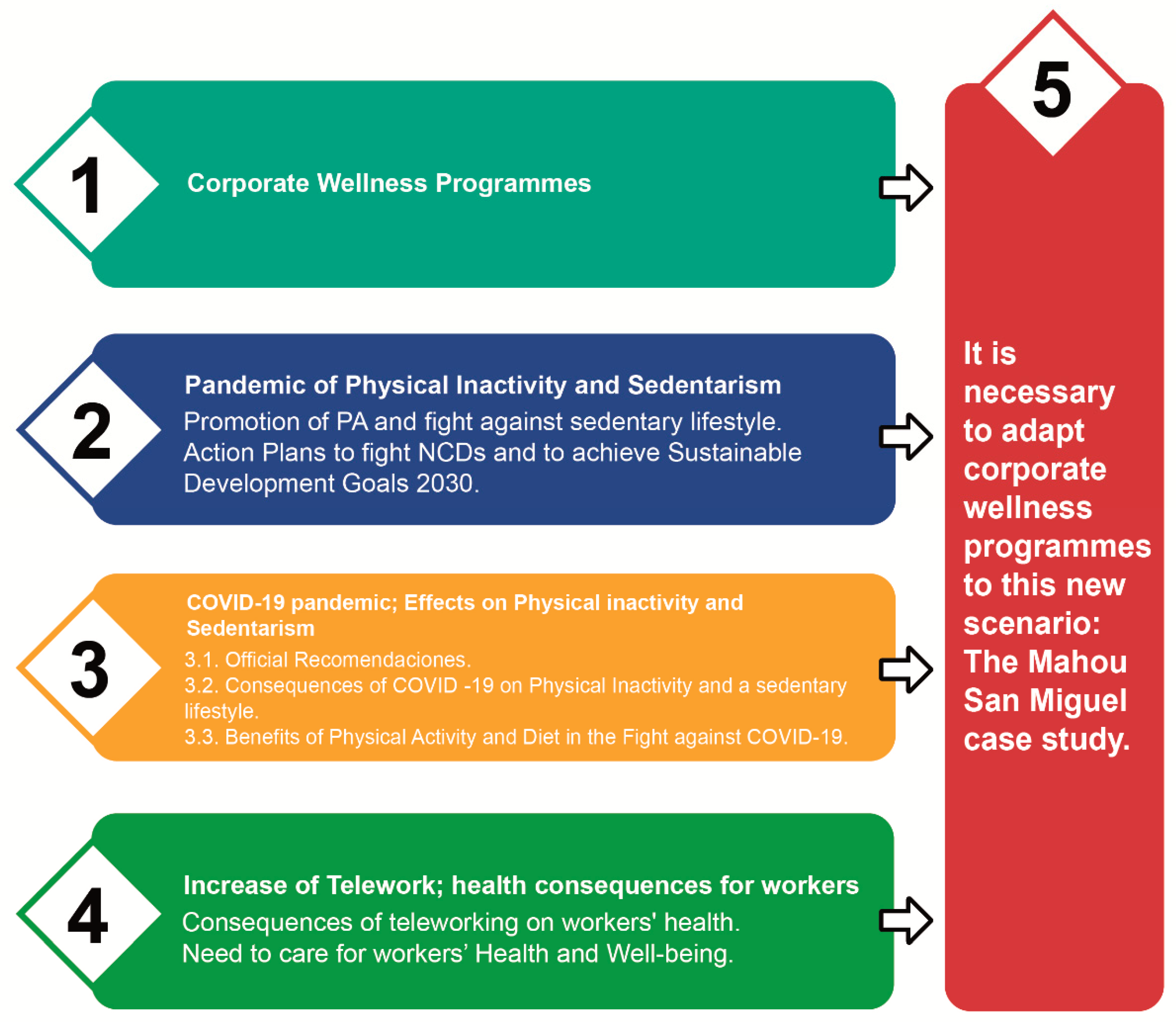

Corporate Well-Being Programme in COVID-19 Times. The Mahou San Miguel Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. COVID-19: Relationship with Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Lifestyle

2.2. Increase in Teleworking and Its Implications on Worker Health

3. Method

3.1. The Case Study’s Parameters

3.2. Procedures and Methods

3.3. Data Collection

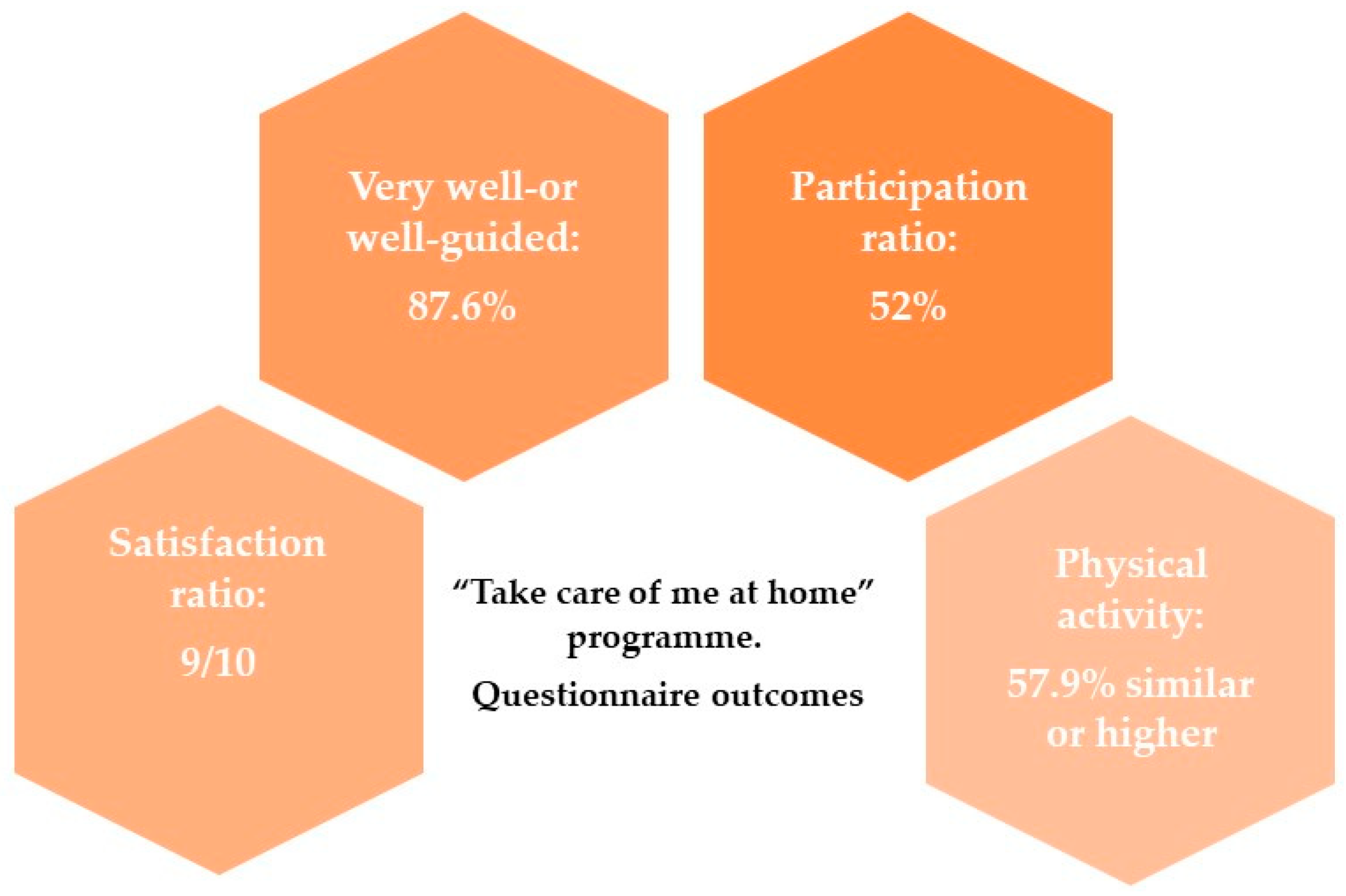

4. Results

- Global actions affecting workers: Information from Mahou San Miguel’s communication team on various activities.

- Actions for physical well-being: Physical activity promotion and Physical activity programme with App Cuidarme (Take care of me). Personalised plans, live and recorded classes.

- Nutrition: Advice and plans through Web Cuidarme (Take care of me) and App.

- Actions for emotional well-being (Happiness): Emotional coach service with coaches from the company itself and Daily Mindfulness sessions early in the morning.

- Actions for psycho-social well-being: Conducting a psychosocial survey.

- Promote Productivity

- Measurement and control of well-being: Number of calls registered on a 24-h emergency telephone number. Number of resolutions to the calls. Participants in streaming, use of App and their individual sport coach, and visualisations of collective online recorded classes.

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Lines of Research

6. Conclusions

Management Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report–51, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10) (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Kohl, H.W., III; Craig, C.L.; Lambert, E.V.; Inoue, S.; Alkandari, J.R.; Leetongin, G.; Kahlmeier, S.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. The pandemic of physical inactivity: Global action for public health. Lancet 2012, 380, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Vaccaro Witt, G.F.; Cabrera, F.E.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. The contagion of sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: The case of isolation in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daszak, P.; Olival, K.J.; Li, H. A strategy to prevent future epidemics similar to the 2019-nCoV outbreak. Biosaf. Health 2020, 2, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, L.M. Novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak: Now is the time to refresh pandemic plans. J. Bus. Contin. Emerg. Plan. 2020, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth, D.H. Evaluating Worksite Health Promotion, 1st ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth, D.H. Worksite Health Promotion, 1st ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Glaros, T.E. Health Promotion: Ideas that Work; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. The Corporate Wellness Segment. A View into Potential Opportunities and Challenges for the Market. 2019. Available online: https://perspectivas.deloitte.com/hubfs/Deloitte-Spain-Wellbeing-Corporate-Business.pdf?hsCtaTracking=250d4b52-8279-410f-9685-f7969c9e9b93%7C186e6283-2ed2-42ef-92fd-152f983cd567 (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Lee, I.-M.; Djoussé, L.; Sesso, H.D.; Wang, L.; Buring, J. Physical activity and weight gain prevention. JAMA 2010, 24, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gil-Beltrán, E.; Meneghel, I.; Llorens, S.; Salanova, M. Get vigorous with physical exercise and improve your well-being at work! Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Chacón, R.; Fernández Martínez, N. Relación entre la práctica de actividad física y los empleados saludables. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2020, 20, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, S.; Cordon, E.; Bailey, C.; Skouteris, H.; Ahuja, K.; Hills, A.P.; Hill, B. The effect of workplace lifestyle programs on diet, physical activity and weight-related outcomes for working women: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, E.; L’Espérance, S.; Mosconi, E. Use of social media platforms for promoting healthy employee lifestyles and occupational health and safety prevention: A systematic review. Safety Sci. 2020, 131, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitsel, L.P.; Arena, R.; Kaminsky, L.A.; Berrigan, D.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Calitz, C.; Pronk, N.P. Assessing physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cardiorespiratory fitness in worksite health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- López Bueno, R.; Casajús Mallén, J.A.; Garatachea Vallejo, N. La actividad física como herramienta para reducir el absentismo laboral debido a enfermedad en trabajadores sedentarios: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Española Salud Pública 2018, 92. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272018000100506&lng=es&tlng= (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Van Amelsvoort, L.; Spigt, M.G.; Swaen, G.M.H.; Kant, I. Leisure time physical activity and sickness absenteeism; A prospective study. Occup. Med. 2006, 56, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gómez-Chacón, R.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M.; Bernal-García, A.; Fernández-Gavira, J. La práctica de actividad física y su relación con la satisfacción laboral en una organización de alimentación. J. Sports Econ. Manag. 2016, 2, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Chacón, R.; Morales-Sánchez, V.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; Muñoz-Llerena, A. La práctica de actividad física y su relación con la satisfacción laboral en una consultora informática. SPORT TK-Rev. Euro Am. Cienc. Deporte 2018, 7, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusa, S.; Punakallio, A.; Mänttäri, S.; Korkiakangas, E.; Oksa, J.; Oksanen, T.; Laitinen, J. Interventions to promote work ability by increasing sedentary workers’ physical activity at workplaces–A scoping review. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 82, 102962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillivray, D. Fitter, happier, more productive: Governing working bodies through wellness. Cult. Organ. 2005, 11, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerden, M.D.; Courtright, S.H.; Widmer, M.A. Why people play at work: A theoretical examination of leisure-at-work. Leis. Sci. 2018, 40, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Kawakami, N. Effects of a multi-component workplace intervention program with environmental changes on physical activity among Japanese white-collar employees: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 25, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.M.N.; Gontijo, L.A.; de Araujo Vieira, E.M.; dos Santos Leite, W.K.; Colaco, G.A.; de Carvalho, V.D.H.; de Souza, E.L.; da Silva, L.B. A worksite physical activity program and its association with biopsychosocial factors: An intervention study in a footwear factory. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2019, 69, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.M.; Coller, R.K.; Pollack Porter, K.M. A qualitative study of facilitators and barriers to implementing worksite policies that support physical activity. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.V.; Winston Paolicelli, C.; Jyothi, V.; Baun, W.; Perkison, B.; Phipps, M.; Montgomery, C.; Feltovich, M.; Griffith, J.; Alfaro, V.; et al. Evaluation of worksite policies and practices promoting nutrition and physical activity among hospital workers. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2016, 9, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, A.H.; Ripp, J.A.; Oh, K.Y.; Basloe, F.; Hassan, D.; Akhtar, S.; Leitman, I.M. The impact of program-driven wellness initiatives on burnout and depression among surgical trainees. Am. J. Surg. 2020, 219, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodson, E.A.; Hipp, J.A.; Lee, J.A.; Yang, L.; Marx, C.M.; Tabak, R.G.; Brownson, R.C. Does availability of worksite supports for physical activity differ by industry and occupation? Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, J.A.; Dodson, E.A.; Lee, J.A.; Marx, C.M.; Yang, L.; Tabak, R.G.; Brownson, R.C. Mixed methods analysis of eighteen worksite policies, programs, and environments for physical activity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chau, J.Y.; Engelen, L.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Young, S.; Olsen, H.; Gilson, N.; Brown, W.J. “In Initiative Overload”: Australian perspectives on promoting physical activity in the workplace from diverse industries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boix-Vilella, S.; León-Zarceño, E.; Serrano-Rosa, M.Á. Niveles de salud psicológica y laboral en practicantes de Pilates/Levels of psychological and occupational health in pilates adherents. Rev. Costarric. Psicol. 2018, 37, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz, X.; Mena, C.B.; Rebolledo, A.C. Propuesta de un programa de promoción de la salud con actividad física en funcionarios públicos. Prax. Educ. 2012, 15, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Loprinzi, P.D. Association between habitual physical activity on episodic memory strategy use and memory controllability. Health Promot. Perspect. 2019, 9, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerber, M.; Jonsdottir, I.H.; Lindwall, M.; Ahlborg, G. Physical activity in employees with differing occupational stress and mental health profiles: A latent profile analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Beltrán, E.; Llorens, S.; Salanova. Employees’ physical exercise, resources, engagement, and performance: A cross-sectional study from HERO model. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2020, 36, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bezner, J.R.; Franklin, K.A.; Lloyd, L.K.; Crixell, S.H. Effect of group health behaviour change coaching on psychosocial constructs associated with physical activity among university employees. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 18, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, M.; Post, D.; Dollman, J.; Parfitt, G. Efficacy of theory-informed workplace physical activity interventions: A systematic literature review with meta-analyses. Health Psychol. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimiro, A.J.; Artés, E.M.; Muyor, J.M.; Rodríguez, M.A. Incidencia de un programa de actividad física en la calidad de vida de los trabajadores en su ámbito laboral. Arch. Med. Deporte 2011, 23, 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-J.; Choo, J. Effects of an integrated physical activity program for physically inactive workers: Based on the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2019, 48, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, D.; Jayawar, M.W.; Muir, S.; Ho, D.; Sackett, O. Increasing awareness of the importance of physical activity and healthy nutrition: Results from a mixed-methods evaluation of a workplace program. J. Phys. Activ. Health 2019, 16, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundwiler, J.; Schüpbach, U.; Dieterle, T.; Leuppi, J.D.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Wolfer, D.P.; Brighenti-Zogg, S. Association of occupational and leisure-time physical activity with aerobic capacity in a working population. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Groenesteijn, L.; Commissaris, D.A.C.M.; Van Den Berg-Zwetsloot, M.; Hiemstra-Van Mastrigt, S. Effects of dynamic workstation Oxidesk on acceptance, physical activity, mental fitness and work performance. Work 2016, 54, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aittasalo, M.; Livson, M.; Lusa, S.; Romo, A.; Vähä-Ypyä, H.; Tokola, K.; Sievänen, H.; Mänttäri, A.; Vasankari, T. Moving to business–Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior after multilevel intervention in small and medium-size workplaces. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flahr, H.; Brown, W.J.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L. A systematic review of physical activity-based interventions in shift workers. Prev. Med. Reports 2018, 10, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Täuber, S.; Mulder, L.B.; Flint, S.W. The impact of workplace health promotion programs emphasizing individual responsibility on weight stigma and discrimination. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbinden-Foncea, H.; Francaux, M.; Deldicque, L.; Hawley, J.A. Does high cardiorespiratory fitness confer some protection against proinflammatory responses after infection by SARS-CoV-2? Obesity 2020, 28, 1378–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaluza, A.J.; Weber, F.; van Dick, R.; Junker, N.M. When and how health-oriented leadership relates to employee well-being—The role of expectations, self-care, and LMX. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.B.; Adrian, A.L.; Hemphill, M.; Scaro, N.H.; Sipos, M.L.; Thomas, J.L. Professional stress and burnout in U.S. military medical personnel deployed to Afghanistan. Mil. Med. 2017, 182, e1669–e1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vincent-Höper, S.; Stein, M. The role of leaders in designing employees’ work characteristics: Validation of the health-and development-promoting leadership behavior questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health 2004. Available online: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/strategy_english_web.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health, 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/ (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf;jsessionid=ADC589EBA2A1E6B5C20D2D6708041334?sequence=1 (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet 2018, 6, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, P.; Mao, L.; Nassis, G.P.; Harmer, P.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Li, F. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Connecting the World to Combat Coronavirus, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Gobierno de España (Spanish Government). Prevención de Riesgos Psicosociales en Situación de Trabajo a Distancia Debida al COVID-19. Recomendaciones Para el Empleador 2020. Available online: https://www.insst.es/documents/94886/712882/Riesgos+psicosociales+y+trabajo+a+distancia+por+covid-19.+Recomendaciones+para+el+empleador.pdf/70cb49b6-6e47-49d1-8f3c-29c36e5a0d0f (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Tison, G.H.; Avram, R.; Kuhar, P.; Abreau, S.; Marcus, G.M.; Pletcher, M.J.; Olgin, J.E. Worldwide effect of COVID-19 on physical activity: A descriptive study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Brach, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Hoekelmann, A. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedad Española de Obesidad, SEEDO Evaluation of Weight Wain in Spain During Confinement. 2020. Available online: www.seedo.es/ (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Castañeda-Babarro, A.; Arbillaga-Etxarri, A.; Gutiérrez-Santamaria, B.; Coca, A. Impact of COVID-19 confinement on the time and intensity of physical activity in the Spanish population. Res. Square 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound and the International Labour Organization. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- E-RH. The Implications of Working Without an Office. 2020. Available online: https://e-rh.net/the-implications-of-working-without-an-office/ (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Gupta, Y.P.; Karimi, J.; Somers, T.M. Telecommuting: Problems associated with communications technologies and their capabilities. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1995, 42, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, J.C.; Gschwind, L. Three generations of Telework: New ICTs and the (R)evolution from home office to virtual office. New technology. Work Employ. 2016, 31, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiller, C.; Van Der Heijden, B.; Chedotel, F.; Dumas, M. “You have got a friend”: The value of perceived proximity for teleworking success in dispersed teams. Team Perform. Manag. 2019, 25, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-ILO. Project “Towards Safe, Healthy and Declared Work in Ukraine”. Available online: www.ilo.org/shd4Ukraine (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Metzger, J.L.; Cléach, O. White-collar telework: Between an overload and learning a new organization of time. Sociol. Trav. 2004, 46, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinen De Bruin, Y.; Lequarre, A.; Mccourt, J.; Clevestig, P.; Pigazzani, F.; Zare Jeddi, M.; Goulart De Medeiros, M. Initial impacts of global risk mitigation measures taken during the combatting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Safety Sci. 2020, 128, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Adecco Group. Resetting Normal: Redefiniendo la Nueva Era de Trabajo, 2020. Available online: https://www.adeccoinstitute.es/informes/resetting-normal-redefiniendo-la-nueva-era-del-trabajo/ (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Consejo Superior de Deportes de España and Instituto Nacional de Seguridad e Higiene en el Trabajo (INSHT). Socio-Economic Assessment of a Physical Activity Programme for the Employees of a Company 2013. Available online: https://www.insst.es/documents/94886/96076/valoracion+socio+economica/d1ab56dd-85bf-47cf-bba1-35d16244f839 (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Bartunek, J.M.; Rynes, S.L.; Irland, R.D. What makes management research interesting, and why does it matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotto, F.L.; Zanni, P.P.; Moraes, G.S.M. What is the use of a single-case study in management research? Rev. Adm. Empresas 2014, 54, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating.Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jersild, A.T.; Meigs, M.F. Chapter V: Direct observation as a research method. Rev. Educ. Res. 1939, 9, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Fernández, J.; Gálvez Ruiz, P.; Velez Colon, L.; Bernal García, A. Service convenience, perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: A study of consumers from low-cost fitness centers in Spain. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2016, 16, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Willits, F.K.; Theodori, G.L.; Luloff, A. Another look at Likert scales. J. Rural Soc. Sci. 2016, 31. Available online: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol31/iss3/6 (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Robroek, S.; van Lenthe, F.J.; van Empelen, P.; Burdorf, A. Determinants of participation in worksite health promotion programmes: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sallis, R.; Young, D.R.; Tartof, S.Y.; Sallis, J.F.; Sall, J.; Li, Q.; Smith, G.N.; Cohen, D.A. Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: A study in 48,440 adult patients. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Nicás, S.; Moncada, S.; Llorens, C.; Navarro, A. Working conditions and health in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic: Minding the gap. Safety Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.; Artioli, G.G.; Gualano, G. Risk of increased physical inactivity during COVID-19 outbreak in older people: A call for actions. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 1126–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.J.; Huebner, W.W.; Yarborough, C.M. Characteristics of participants and nonparticipants in worksite health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 11, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, C.A.; Inglish, P. Are employees who are at risk for cardiovascular-disease joining worksite fitness centers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1996, 38, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Misra, M. Linking corporate social responsibility (CSR) and organizational performance: The moderating effect of corporate reputation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, F.; Felfe, J.; Pundt, A. The impact of health-oriented leadership on follower health: Development and test of a new instrument measuring health-promoting leadership. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Z. Pers. 2014, 28, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooksbank, R. Defining the small business: A new classification of company size. Entrep. Reg. Dev. Int. J. 1991, 3, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Núñez-Sánchez, J.M.; Gómez-Chacón, R.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; García-Fernández, J. Corporate Well-Being Programme in COVID-19 Times. The Mahou San Miguel Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6189. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13116189

Núñez-Sánchez JM, Gómez-Chacón R, Jambrino-Maldonado C, García-Fernández J. Corporate Well-Being Programme in COVID-19 Times. The Mahou San Miguel Case Study. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6189. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13116189

Chicago/Turabian StyleNúñez-Sánchez, José M., Ramón Gómez-Chacón, Carmen Jambrino-Maldonado, and Jerónimo García-Fernández. 2021. "Corporate Well-Being Programme in COVID-19 Times. The Mahou San Miguel Case Study" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6189. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13116189