Sublime Experience for Sustainable Underground Space: Integration of the Artists’ Works in Chichu Art Museum

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Reinterprets the notion of the sublime experience through the imagination, as shown in artforms such as myths, novels, and paintings (in Section 2.1);

- Locates the concept and meaning of sublime experience within the aesthetic discussion that can be had in underground spaces (in Section 2.2);

- Analyzes the Chichu Art Museum in Japan as the representative underground museum, in terms of sustainable relations between architectural spaces and nature, such as through light, darkness and geometric form, with sublime experiences based on the correlations between architectural spaces and artworks (in Section 3).

2. The Sublime, the Underground and Artworks

2.1. The Sublime Experience

2.2. A Vision of the Underground Imagination in Art

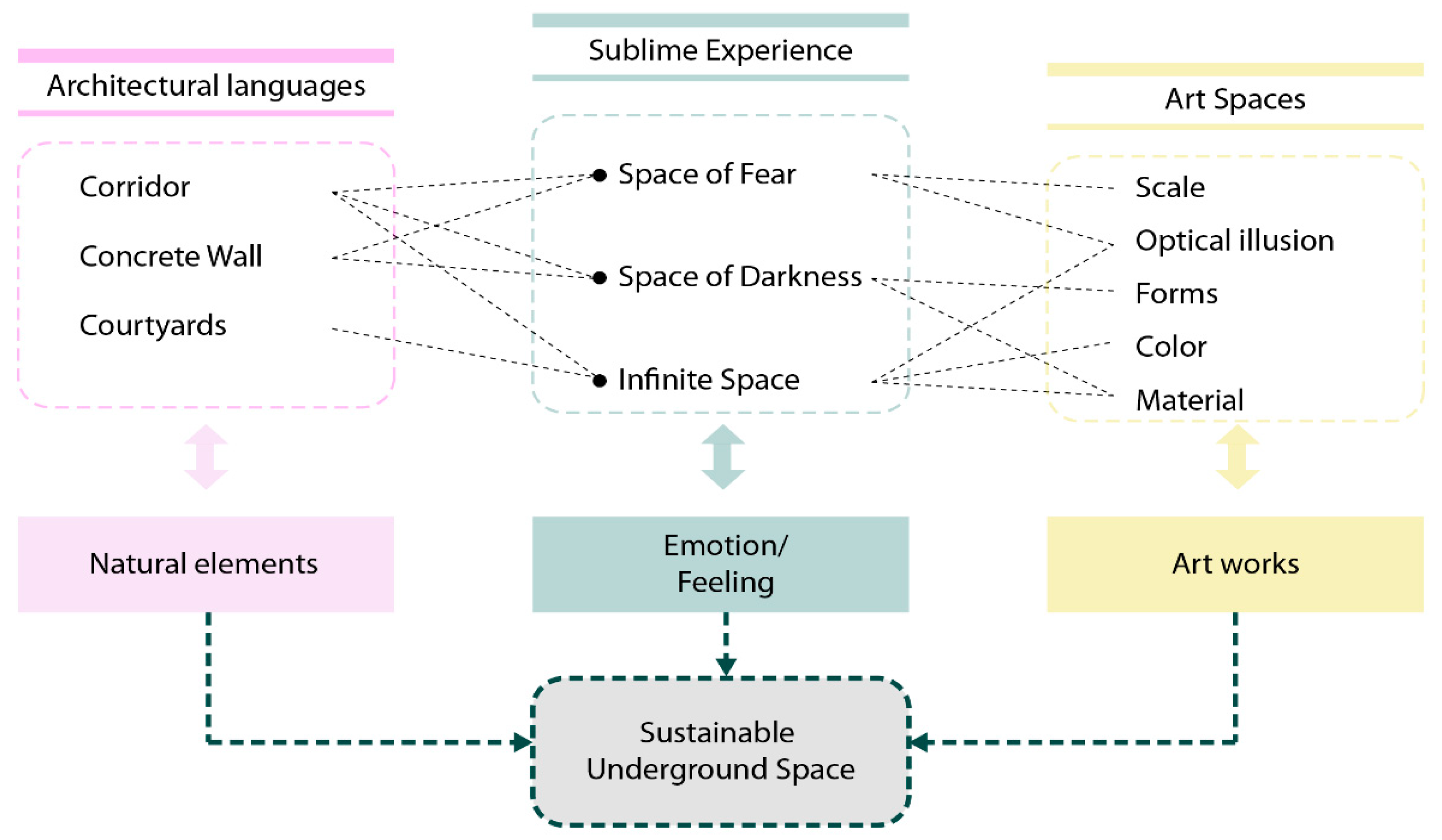

2.3. Framework

3. The Sublime Experience Underground: A Review

3.1. Context: Chichu Art Museum in Naoshima

3.2. The Sublime Experience of the Chichu Art Museum

3.2.1. The Architectural Languages

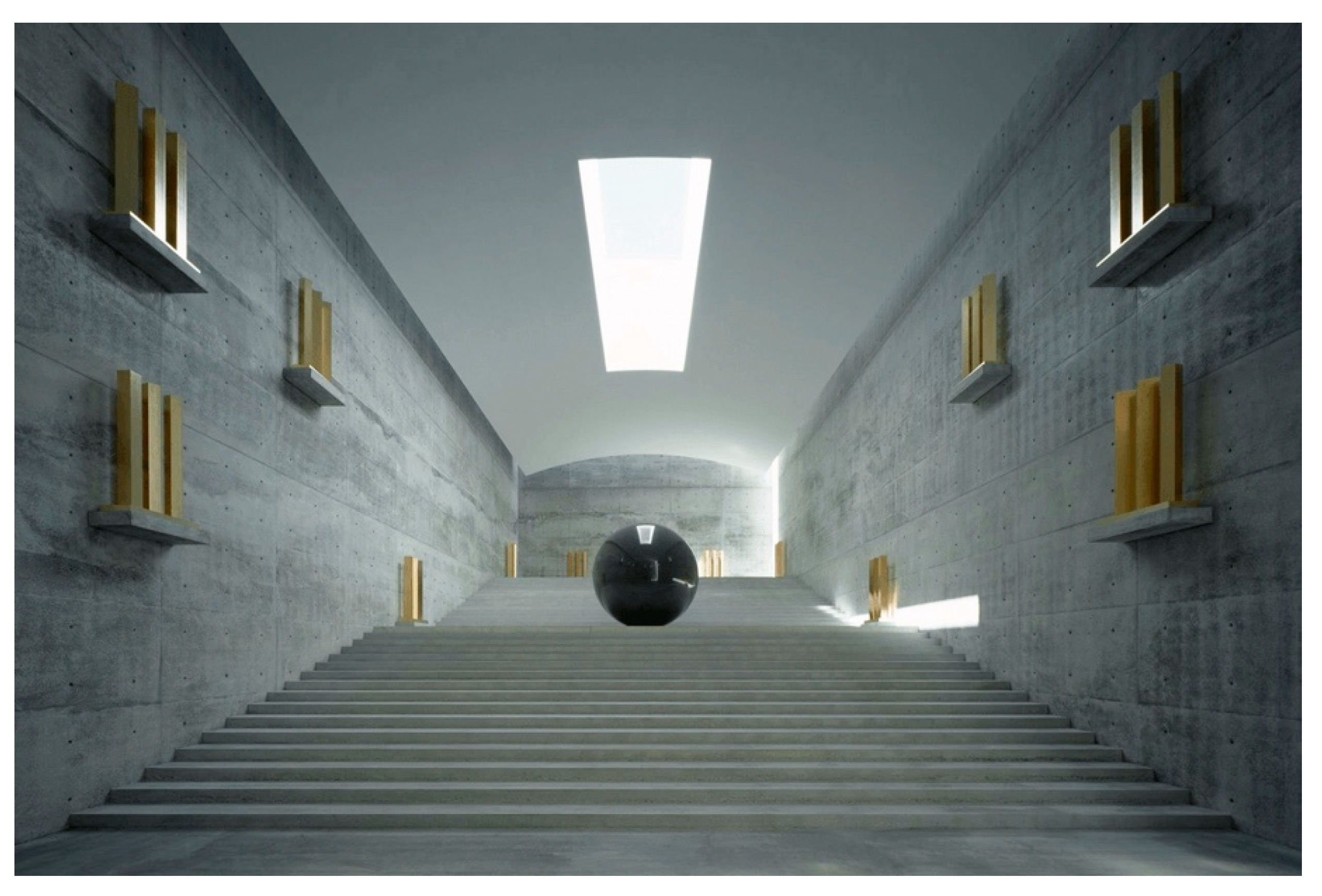

3.2.2. The Entrance and Corridor

3.2.3. Two Courtyards

3.3. Architecture Integration of Artists’ Works

3.3.1. James Turrell

3.3.2. Claude Monet

3.3.3. Walter de Maria

4. Discussion

4.1. The Matrix of the Integration of the Sublime Experience with the Artworks in Chichu Art Museum

4.2. Synergistic Influence of the Place in Which Art Is Presented on Its Perception

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Münz, R. Overcrowded World?: Global Population and International Migration; Haus Publishing: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, S.; Parent, J.; Civco, D.L.; Blei, A.; Potere, D. The dimensions of global urban expansion: Estimates and projections for all countries 2000–2050. Prog. Plan. 2011, 75, 53–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broere, W. Urban underground space: Solving the problems of today’s cities. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durmisevic, S. The future of the underground space. Cities 2016, 16, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, R.; Admiraal, H.; Bobylev, N.; Parker, H.; Godard, J.-P.; Vahaaho, I.; Rogers, C.D.F.; Shi, X.; Hanamura, T. Sustainability Issues for Underground Space in Urban Areas. Urban Des. Plan. 2012, 165, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlefield, D. (Re)generation: Place, Memory, Identity. Archit. Des. 2012, 82, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elrahman, A.S.; Asaad, M. Urban Design & Urban Planning: A Critical Analysis to the Theoretical Relationship Gap. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2020, 12, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar]

- Aldız, E.; Aydın, D.; Sıramkaya, S.B. Loss of city identities in the process of change: The city of Konya-Turkey. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 140, 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Susanne, K. Langer, Feeling and Form a Theory of Art (Chapter 6). In The Modes of Virtual Space; Developed from Philosophy in a New Key; Routledge: London, UK, 1953; pp. 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, S. The Culture of Time and Space; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kwinter, S. Architectures of Time: Toward a Theory of the Event in Modernist Culture; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays; Garland Publishing Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, G. The Poetics of Space; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Building, Dwelling, Thinking. In Poetry, Language, Thought; Duke University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971; pp. 145–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bobylev, N. Mainstreaming sustainable development into a city’s Master plan: A case of Urban Underground Space use. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, J.S.; Holm, L.E. Architecture and the Unconscious; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.-C.; Yu, C.-Y. Aesthetic Experience as an Essential Factor to Trigger Positive Environmental Consciousness. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nancy, J.-L. Du Sublime; 1988 Editions Berlin; Moonji Publishing: Seoul, Korea, 2005; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cronk, N. The Classical Sublime: French Neoclassicism and the Language Of Literature; Rookwood Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, W. Longinus on the Sublime: The Greek Text Edited after the Paris Manuscript; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lyotard, J.F. Presenting the Unpresentable: The Sublime. Art Forum 1984. Available online: https://www.artforum.com/print/198204/presenting-the-unpresentable-the-sublime-35606 (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Theriault, N. The Role of the Sublime in Art, Literature, and Psychology. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, A. Nature and Landscape: An. Introduction to Environmental Aesthetics; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, E. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful and Other Pre-Revolutionary Writings; Wormersley, D., Ed.; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shelley, J. 18th Century British Aesthetics. 2006. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aesthetics-18th-british/ (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Burke, E. On the Sublime and Beautiful; Good Press: Glasgow, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt, K. The sublime and modern architecture: Unmasking (an aesthetic of) abstraction. New Lit. Hist. 1995, 26, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyn, F. Expressive Uncertainty: Edmund Burke’s Theory of the Sublime and Eighteenth-Century Conceptions of Metaphor. In The Science of Sensibility: Reading Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, T. The emotional experience of the sublime. Can. J. Philos. 2012, 42, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L. Sublime Resources: A Brief History of The Notion of the Sublime. Luke White Home Page. Available online: http://www.lukewhite.me.uk/sub_history.htm (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Korsmeyer, C. Fear and Disgust: The Sublime and the Sublate. Revue Int. Philos. 2008, 4, 367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.H. Notes on the Underground: An Essay of Technology, Society, and the Imagination; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Social Commission and the Autonomous Architect. Harv. Archit. Rev. 1987, 6, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn, R. ‘Being’ as a concept of aesthetics. Br. J. Aesthet. 1968, 8, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlovitch, S. Offending against nature. Environ. Values 1998, 7, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, R. Landscape and the metaphysical imagination. In The Aesthetics of Natural Environments; Carlson, A., Berleant, A., Eds.; Broadview Press: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2004; pp. 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- De Bolla, P. Toward the Materiality of Aesthetic Experience. Diacritics 2002, 32, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les Enfers—Par François de Nomé. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Les_enfers_-_par_Fran%C3%A7ois_de_Nom%C3%A9_(dit_Mons%C3%B9_Desiderio).jpg (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Verne, J. Journey to the Center of the Earth; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Davidson, J.; Cameron, L.; Bondi, L. Geography and Emotion—Emerging Constellations. In Emotion, Place and Culture; Smith, M., Davidson, J., Cameron, L., Bondi, L., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Voyage au Centre de la Terre. Available online: https://unframed.lacma.org/2013/12/12/right-place-right-action-right-time-tadao-ando-and-walter-de-maria (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Junghwa, L. Urban Subterranean Space: A link Between a Ground Level Public Space and Underground Infrastructure. Graduate Thesis, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Princeton University Art Museum. Available online: https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/2969 (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Bate, W. From Classic to Romantic: Premises of Taste in Eighteenth-Century England; Harper Torchbooks: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Funck, C.; Chang, N. Island in Transition: Tourists, Volunteers and Migrants Attracted by an Art-Based Revitalization Project in the Seto Inland Sea. Tour. Transit. 2018, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soichiro, F.; Benesse, T.A. Showing the World a Way to Make Communities More Sustainable; Benesse Integrated Report; Benesse Holdings Inc.: Shinjuku, Japan, 2018; pp. 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Miwon, K. A Position of Elsewhere: Lessons From Naoshima; Naoshima, Nature∙Art∙Architecture; Hatje Cantz: Verlag, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.; Lee, J. Community Cultural Resources as Sustainable Development Enablers: A Case Study on Bukjeong Village in Korea compared with Naoshima Island in Japan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tadao, A. Chichu Art Museum; AXIS: Tokyo, Japan, 2004; pp. 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Benesse Art Site Naoshima. History of Benesse Art Site Naoshima. Available online: https://benesse-artsite.jp/en/art/chichu.html (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Corcoran, D. Right Place, Right Action, Right Time: Tadao Ando and Walter de Maria. Available online: www.unframed.lacma.org/2013/12/12/right-place-right-action-right-time-tadao-ando-and-walter-de-maria (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Tadao, A. Naoshima; Exhibition Book; Le Bon Marche Rive Gauche: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ando Tadao Architect—Ahngraphics. 2009. Available online: https://www.japan-experience.com/to-know/understanding-japan/the-architect-tadao-ando (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Tadao, A. Tadao, Ando—Process and Idea; TOTO: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Imagination Medium | Myth | Noble | Painting |

|---|---|---|---|

| François de Nomé, “Hell” (1622) | Jules Verne, “Journey to the Center of the Earth” (1864) | Giovanni Battista Piranesi, “Imaginary Prison” (1761) | |

| Characteristics |

|

|

|

| Summary of Sublime Experience |

| ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, E.J.; Kang, E. Sublime Experience for Sustainable Underground Space: Integration of the Artists’ Works in Chichu Art Museum. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6653. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13126653

Park EJ, Kang E. Sublime Experience for Sustainable Underground Space: Integration of the Artists’ Works in Chichu Art Museum. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6653. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13126653

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Eun Joo, and Eunki Kang. 2021. "Sublime Experience for Sustainable Underground Space: Integration of the Artists’ Works in Chichu Art Museum" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6653. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13126653