Customer Behavioral Reactions to Negative Experiences during the Product Return

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty

2.2. Consumer Behavior and SCM

2.3. Consumers’ Returning Behaviour

3. Methodology

- -

- 48% of male and 52% of female,

- -

- 60% of people aged 25 to 46.

4. Analysis of Test Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Finding and Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chkanikova, O.; Sroufe, R. Third-party sustainability certifications in food retailing: Certification design from a sustainable supply chain management perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 124344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, D.; Tyan, J.; Sroufe, R. Drivers of sustainable supply chain management: Practices to alignement with un sustainable development goals. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 14, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kros, J.F.; Falasca, M.; Dellana, S.; Rowe, W.J. Mitigating counterfeit risk in the supply chain: An empirical study. TQM J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, V.; Schoenherr, T.; Charan, P. The thematic landscape of literature in sustainable supply chain management (SSCM): A review of the principal facets in SSCM development. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 1091–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Reefke, H.; Ahmed, M.D.; Sundaram, D. Sustainable supply chain management—Decision making and support: The SSCM maturity model and system. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2014, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavaliere, A.; Pigliafreddo, S.; De Marchi, E.; Banterle, A. Do Consumers Really Want to Reduce Plastic Usage? Exploring the Determinants of Plastic Avoidance in Food-Related Consumption Decisions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Lee, H. Young Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of sustainability in the apparel industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, D.; Madzik, P.; Sroufe, R. The Influence of ISO 9001 & ISO 14001 on Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Textile Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4282. [Google Scholar]

- Baliga, R.; Raut, R.; Kamble, S. The effect of motivators, supply, and lean management on sustainable supply chain management practices and performance: Systematic literature review and modeling. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 27, 347–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.S.; Bahinipati, B.; Jain, V. Sustainable supply chain management: A review of literature and implications for future research. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2019, 30, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.A.; Kumar, V. Can Product Returns Make You Money? MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2010, 51, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Baiman, S.; Fischer, P.E.; Rajan, M.V. Information, contracting, and quality costs. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.L. Remote Purchase Environments: The Influence of Return Policy Leniency on Two-Stage Decision Processes. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Retail Return Policy, Endowment Effect, and Consumption Propensity: An Experimental Study. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2009, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C. Fradulent return proclivity: An empirical analysis. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.T.; Hansen, K. The option value of returns: Theory and empirical evidence. Mark. Sci. 2009, 28, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, B.; Chen, J. When to introduce an online channel, and offer money back guarantees and personalized pricing? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 257, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R. Product categories, returns policy and pricing strategy for e-marketers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2009, 18, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.R. The 7 Deadly Sins of Reverse Logistics. Mater. Handl. Manag. 2001, 56, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Huang, Z.S.; Liu, B. Return strategies and online product customization in a dual-channel supply chain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janakiraman, N.; Syrdal, H.A.; Ryan Freling, F. The Effect of Return Policy Leniency on Consumer Purchase and Return Decisions: A Meta-analytic Review. J. Retail. 2016, 92, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakiraman, N.; Ordónez, L. Effect of Effort and Deadlines on Consumer Product Returns. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Gerstner, E.; Hagerty, M. Money back guarantees in retailing: Matching products to consumers Tastes. J. Retail. 1995, 71, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Xiao, T.; Yu, Y.; Robb, D.J. Quality disclosure strategy in a decentralized supply chain with consumer returns. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 27, 2139–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, K.D.; Boyd, E. Information and its impact on consumers’ reactions to restrictive return policies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Fornell, C. A Framework for Comparing Customer Satisfaction Across Individuals and Product Categories. J. Econ. Psychol. 1991, 12, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeithaml, V.; Berry, L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.; Arnold, M. Customer loyalty to the salesperson and the store: Examining relationship customers in an upscale retail context. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2000, 20, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzell, P. The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America; Exclusive Brands Llc.: Livonia, MI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C. A National Customer Satisfaction Barometer: The Swedish Experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pong, L.T.; Yee, P.T. An Integrated Model of Service Loyalty; Academy of Business & Administrative Sciences International Conferences: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deming, W. Out of the Crisis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986; pp. 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, J. Customer Loyalty: How To Earn It, How To Keep It; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kandampully, J. Service Quality to Service Loyalty: A Relationship Which Goes Beyond Customer Services. Total Qual. Manag. 1998, 9, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Møller, C. A Complaint is a Gift. Recovering Customer Loyalty when Things Go Wrong; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, J. Identification of Mass Event Customers and Factors Exerting Influence upon their Satisfactionwith Participation in an Event. Qual. Access Success 2019, 20, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, A.-P.; Peng, C.L.; Huang, H.C.; Yeh, S.P. Effects of corporate social responsibility on firm performance: Does customer satisfaction matter? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, C. Some Reasons to Implement Reverse Logistics on Companies. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2013, 16, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Corporate Executive Board Company. An Excerpt from Shifting the Loyalty Curve Mitigating Disloyalty by Reducing Customer Effort; The Corporate Executive Board Company: Arlington, VA, USA, 2009; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Stum, D.; Thiry, A. Building Customer Loyalty. Train. Dev. J. 1991, 45, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, G.; Dangayach, S. Sharma, Service Recovery Paradox: The Success Parameters. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2014, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoui, F. Customer service in supply chain management: A case study. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2014, 27, 786–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, J.; Lehmusvaara, A.; Tuominen, M. Customer service based design of the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2001, 69, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.Y.; Lai, K.; Cheng, T.C.E.; Lun, Y.H.V. The role of IT-enabled collaborative decision making in inter-organizational information integration to improve customer service performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 159, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, F. Strategic customer behavior, commitment, and supply chain performance. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1759–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madzík, P.; Pelantová, V. Validation of product quality through graphical interpretation of the Kano model: An explorative study. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 1956–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzík, P. Increasing accuracy of the Kano model–a case study. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.W.; Lee, Y.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Hwang, M.K. A framework for measuring the performance of service supply chain management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2012, 62, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chen, X.; Cai, C.; Guan, S. Supply chain coordination of fresh agricultural products based on consumer behavior. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 123, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lambert, D.M. Segmentation of Markets Based on Customer Service. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 1994, 24, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chen, Y.-R.; Zhou, X.-T.; Fang, J. Consumer behavior in the omni-channel supply chain under social networking services. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1785–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, T.; Zimon, D.; Kaczor, G.; Madzík, P. The impact of the level of customer satisfaction on the quality of e-commerce services. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2019, 69, 666–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. Consumer returns policies and supply chain performance. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2009, 11, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woźniak, J.; Fill, K. Logistic organization of mass events in the light of SWOT analysis-case study. TEM J. 2018, 7, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Zimon, D.; Madzik, P.; Sroufe, R. Management systems and improving supply chain processes: Perspectives of focal companies and logistics service providers. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 939–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Shi, J. Consumer returns reduction and information revelation mechanism for a supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2016, 240, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A.; Dumay, J.; Palmaccio, M.; Celenza, D. Knowledge transfer in a start-up craft brewery. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2019, 25, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Govindan, K.; Xu, X. Consumer returns policies with endogenous deadline and supply chain coordination. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 242, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, D.F. Introduction to Management of Reverse Logistics and Closed Loop Supply Chain Processes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barratt, E.S. Impulsivity: Integrating Cognitive, Behavioral, Biological, and Environmental Data. In The Impulsive Client: Theory, Research, and Treatment; American Psychological Association (APA): Worcester, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bernon, M.; Cullen, J.; Gorst, J. Online retail returns management: Integration within an omni-channel distribution context. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 584–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greatorex, M.; Mitchell, V.W. Modelling Consumer RiskReduction Preferences from Perceived Loss Data. J. Econ. Psychol. 1994, 15, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Grewal, D.; Levy, M. Customer satisfaction/logistics interface. J. Bus. Logist. 1995, 16, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Vonderembse, M.A.; Lim, J. Logistics flexibility and its impact on customer satisfaction. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2005, 16, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, K.R. The connection between your employees and customers. J. Adv. Res. Bus. Manag. Account. 2018, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rokonuzzaman, M.; Mukherjee, A.; Iyer, P.; Mukherjee, A. Relationship between retailers’ return policies and consumer ratings. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 35, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülkü, M.A.; Gürler, Ü. The impact of abusing return policies: A newsvendor model with opportunistic consumers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 203, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokonuzzaman, M.; Iyer, P.; Harun, A. Return policy, No joke: An investigation into the impact of a retailer’s return policy on consumers’ decision making. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell-Legner, R. Understanding Customers. Available online: http://ww2.glance.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Counting-the-customer_-Glance_eBook-4.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Narvar. Narvar Consumer Report. 2017. Available online: https://see.narvar.com/rs/249-TEC-877/images/Narvar_Consumer_Survey_ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

| Question: | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age: | ||

| up to 25 years | 41 | 12.5% |

| 26–45 years | 128 | 39.1% |

| 46–60 years | 48 | 14.7% |

| over 60 years old | 110 | 33.6% |

| Sex: | ||

| female | 162 | 49.5% |

| male | 165 | 50.5% |

| Place of residence: | ||

| village | 125 | 38.2% |

| city up to 50,000 | 47 | 14.4% |

| city 50,000–150,000 | 42 | 12.8% |

| city 150,000–500,000 | 46 | 14.1% |

| city with over 500,000 | 67 | 20.5% |

| Education: | ||

| basic | 5 | 1.5% |

| professional | 17 | 5.2% |

| technical secondary | 82 | 25.1% |

| general secondary education | 93 | 28.4% |

| higher | 130 | 39.8% |

| Average net income: | ||

| Up to PLN 1000 | 23 | 7.0% |

| PLN 1001–2000 | 98 | 30.0% |

| PLN 2001–3000 | 93 | 28.4% |

| PLN 3001–4000 | 60 | 18.3% |

| over PLN 4000 | 53 | 16.2% |

| Professional situation: | ||

| unemployed | 30 | 9.2% |

| student | 21 | 6.4% |

| have own business | 12 | 3.7% |

| employed in a company/institution | 147 | 45.0% |

| pensioner | 117 | 35.8% |

| n = 327 | ||

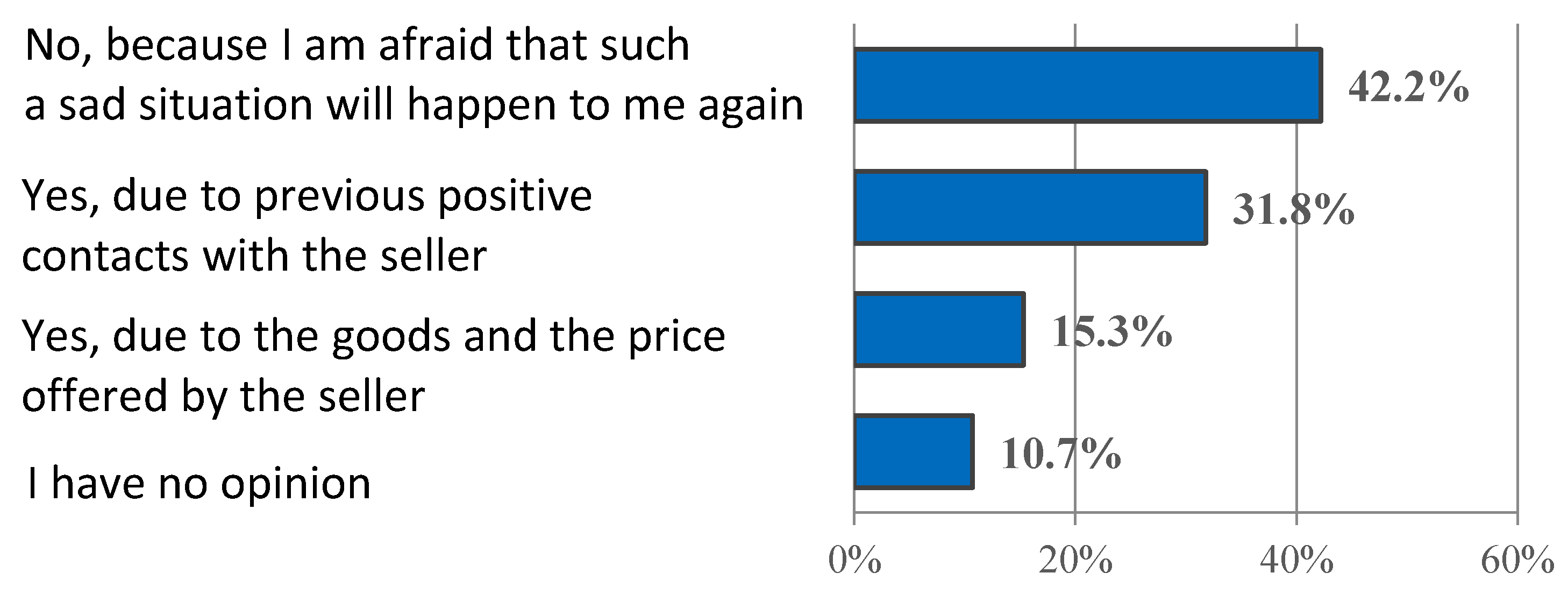

| Answer | Up to PLN 1000 [n = 23] | PLN 1001–2000 [n = 98] | PLN 2001–3000 [n = 93] | PLN 3001–3000 [n = 60] | Over PLN 4000 [n = 53] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes, due to the goods and the price offered by the seller | 13.0% | 17.4% | 9.7% | 21.7% | 15.1% |

| yes, due to previous positive contacts with the seller | 39.1% | 21.4% | 34.4% | 31.7% | 43.4% |

| no, because I am afraid that such a sad situation will happen to me again | 30.4% | 44.9% | 49.5% | 41.7% | 30.2% |

| I have no opinion | 17.4% | 16.3% | 6.5% | 5.0% | 11.3% |

| in total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Statistical significance | χ2 = 21.174185, df = 12, p = 0.047887 | ||||

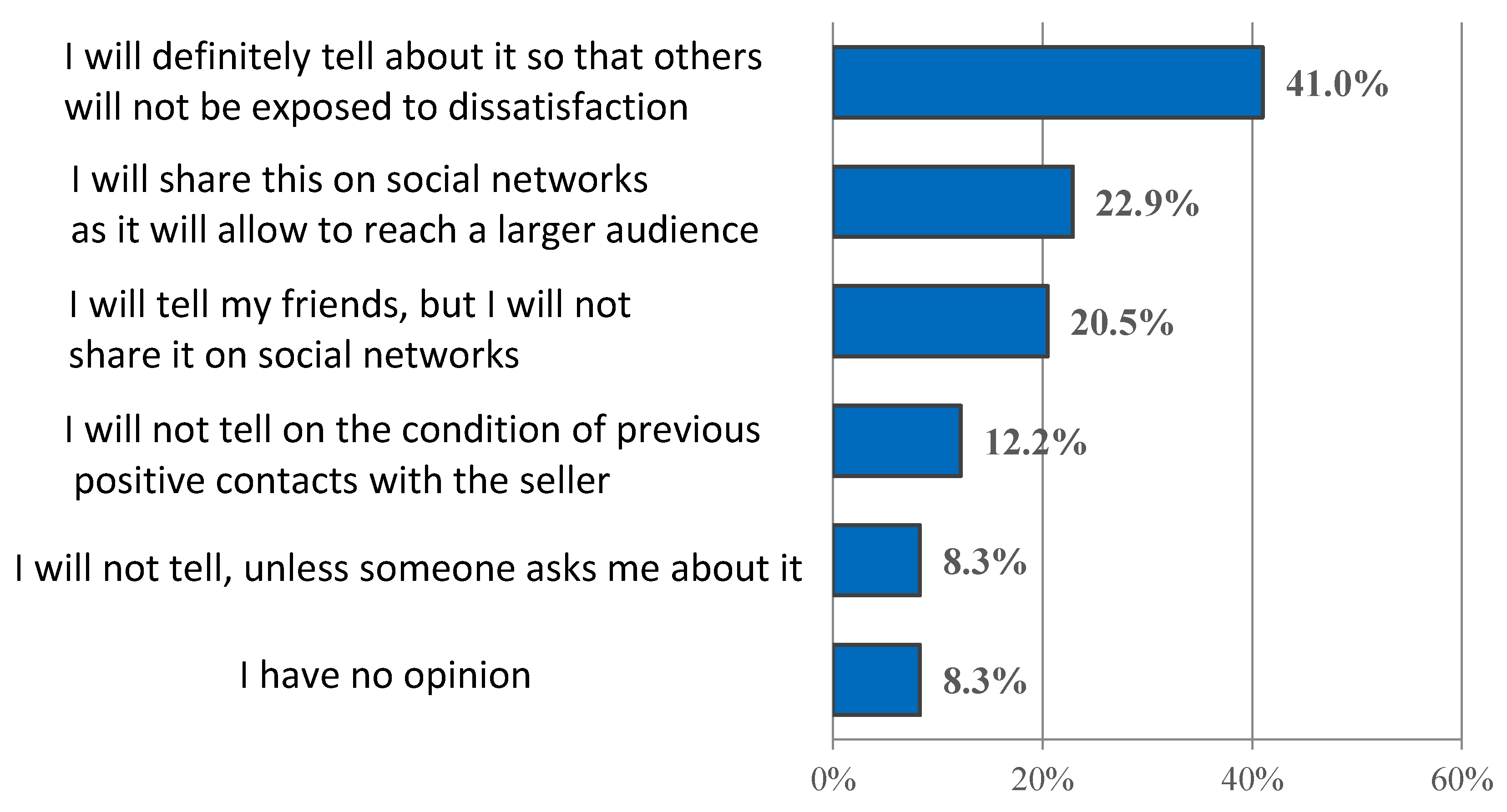

| Answer | Up to 25 Years [n = 41] | 26–45 Years [n = 128] | 46–60 Years [n = 48] | Over 60 Years Old [n = 110] | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I will definitely tell about it so that others will not be exposed to dissatisfaction | 34.2% | 40.6% | 37.5% | 45.5% | χ2 = 1.949238 df = 3 p = 0.583009 |

| I will share this on social networks as it will allow to reach a larger audience | 19.5% | 21.9% | 35.4% | 20.0% | χ2 = 5.119999 df = 3 p = 0.163218 |

| I will tell my friends, but I will not share it on social networks | 26.8% | 21.9% | 20.8% | 16.4% | χ2 = 2.315232 df = 3 p = 0.509609 |

| I will not tell on the condition of previous positive contacts with the seller | 4.9% | 8.6% | 12.5% | 19.1% | χ2 = 8.466746 df = 3 p = 0.037289 |

| I will not tell, unless someone asks me about it | 14.6% | 8.6% | 4.2% | 7.3% | – |

| I have no opinion | 9.8% | 11.7% | 4.2% | 5.5% | – |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lysenko-Ryba, K.; Zimon, D. Customer Behavioral Reactions to Negative Experiences during the Product Return. Sustainability 2021, 13, 448. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13020448

Lysenko-Ryba K, Zimon D. Customer Behavioral Reactions to Negative Experiences during the Product Return. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):448. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13020448

Chicago/Turabian StyleLysenko-Ryba, Kateryna, and Dominik Zimon. 2021. "Customer Behavioral Reactions to Negative Experiences during the Product Return" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 448. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su13020448