Sustainable Supply Chain Engagement in a Retail Environment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Defining Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the Evolution of Sustainability

…the strategic, transparent integration and achievement of an organization’s social, environmental, and economic goals in the systemic coordination of key inter-organizational business processes for improving the long-term economic performance of the individual company and its supply chains.(p. 368)

2.2. The Role of Stakeholders and Supplier Engagement

3. Methodology

3.1. Primary Research

3.2. Sampling Process

3.3. Measuring Instrument

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Findings

- Level 1: Setting expectations

“There are specific guidelines, specific sections: one is about energy, one is about water and the other is waste.”“The document gives a specific categories to look at. Energy stands on its own, water stands on its own, and waste stands on its own.”

“It’s the few discussions I personally had, but there is no other media that I know of.”“No [no other media], but it would be very nice to know what other places are doing.”“No, just the scorecard.”

- Level 2: Monitoring and audits

“[The retailer] does have another scorecard, but it’s more a commercial and technical thing.”

- Level 3: Remediation and supplier capability building

“Jip. If people need training or extra information is needed.”“Definitely, yes. I don’t talk to them that much, but he is definitely open and I’m sure the times that we have spoken he was very keen on helping.”

- Level 4: Partnerships/Engaging with sub-tier suppliers

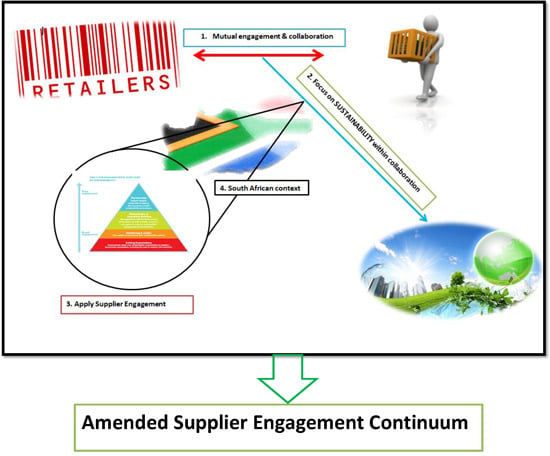

5. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foot, J.; Gaffney, N.; Evans, J. Corporate social responsibility: Implications for performance excellence. Total Qual. Manag. 2010, 21, 799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Thorne, D.M.; Ferrell, L. Social Responsibility and Business, 4th ed. (International edition); Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate sustainability strategies: Sustainability profiles and maturity levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, R.; Clemmensen, S.N.; Pedersen, M.M. The role of corporate sustainability in a low-cost business model—A case study in the Scandinavian fashion industry. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.T.; Weber, J. Business and Society, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Prajogo, D.; Chowdhury, M.; Yeung, A.C.L.; Cheng, T.C.E. The relationship between supplier management and firm’s operational performance: A multi-dimensional perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 136, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.; Fearne, A.; Hornibrook, S.; Hutchinson, K.; Reid, A. Engaging suppliers in CRM: The role of justice in buyer–supplier relationships. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, A.; Henderson, S.; Florence, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Business; Centre for Creative Leadership: Greensboro, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van Marrewijk, M.; Were, M. Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Eth. 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos, G.P. The boundaries of strategic corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 595–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Fraedrich, J. Business Ethics: Ethical DECISION Making and Cases; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.G. Corporate social responsibility: Not whether, but how? Lond. Bus. Sch. 2003, 3, 701. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D.E.; Spekman, R.E.; Kamauff, J.W.; Werhane, P. Corporate social responsibility in supply chains: A procedural justice perspective. Long Range Plan. 2007, 40, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sharma, N. CSR–A business opportunity. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 2009, 44, 396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Retolaza, J.L.; Ruiz, M.; San-Joe, L. CSR in Business start-ups: An application method for stakeholder engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydenberg, S.D. Envisioning socially responsible investing: A model for 2006. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2002, 7, 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer, W.S. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. J. Bus. Eth. 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures-a theoretical foundation. Acc. Audit. Acc. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beder, S. Global Spin: The Corporate Assault on Environmentalism; Chelsea Green Publishing, Inc: Claremont NH, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, K. The world of greenwash. Available online: http://www.corpwatch.org/campaigns/PCDJsp. (accessed on 7 December 2013).

- Parguel, B.; Benoît-Moreau, F.; Larceneux, F. How sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing’: A closer look at ethical corporate communication. J. Bus. Eth. 2011, 102, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P.; Googins, B.K. Stages of Corporate Citizenship: A Developmental Framework; The Boston College Centre for Corporate Citizenship: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, G. Measuring organizational performance: Beyond the triple bottom line. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2009, 18, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2005; University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG. KPMG international corporate responsibility reporting survey 2011. Available online: http://www.kpmg.com/global/en/issuesandinsights/articlespublications/corporate-responsibility/pages/default.aspx (accessed on 19 September 2013).

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Log. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.C.; Lambert, D.M.; Pagh, J.D. Supply chain management: more than a new name for logistics. Int. J. Log. Manag. 1997, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.F. Competing through Supply Chain Management; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.R.; Wood, D.F. Contemporary Logistics, 10th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, J.R.; Boyer, S.L.; Harmon, T. Research opportunities in supply chain management. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, C.J.; Kleindorfer, P.R. Environmental management the operations management: Introduction to the third special issue. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2003, 12, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, J.D.; Klassen, R.; Jayaraman, V. Sustainable supply chains: An introduction. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redclift, M. Sustainable development (1978–2005): An oxymoron comes of age. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Handfield, R.; Nichols, E. Supply Chain Redesign; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bsigroup. ISO 14001 Environmental Management. Available online: http://0-www-bsigroup-com.brum.beds.ac.uk/en-GB/iso-14001-environmental-management/ (accessed on 5 April 2015).

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: New Delhi, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, B.; Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S. Business Research Methods, 3rd ed. (European Edition); McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Towards utility in reviews of multi-vocal literatures. Rev. Educ. Res. 2002, 61, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, H. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 2011, 11, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, M.; McKenzie, H. The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2006, 45, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Global Compact. Supply chain sustainability: A practical guide for continuous improvement. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/Issues/supply_chain/guidance_material.html (accessed on 2 February 2013).

- ATLAS.ti. Available online: http://www.atlasti.com/index.html (accessed on 10 March 2013).

- Bryman, A.; Bell, A. Business Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zikmund, W.G.; Babin, B.J. Exploring Marketing Research: Sampling Designs and Sampling Procedures; South-Western Cengage Learning: Long Island, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boeije, H. Analysis in Qualitative Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Learning for sustainability. Learning for sustainability: Introduction. Available online: http://learningforsustainability.net/ (accessed on 27 March 2015).

- UNESCO. Contributing to a more sustainable future: Quality education, life skills and education for sustainable development. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001410/141019e.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2015).

- UNESCO. Education for sustainable development. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda/education-for-sustainable-development/education-for-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 27 March 2015).

- PWC. Monitoring and Reporting. Available online: http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/sustainability/services/monitoring-and-reporting.jhtml (accessed on 27 March 2013).

- United Nations. General Assembly Resolution 58/219; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berning, A.; Venter, C. Sustainable Supply Chain Engagement in a Retail Environment. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6246-6263. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su7056246

Berning A, Venter C. Sustainable Supply Chain Engagement in a Retail Environment. Sustainability. 2015; 7(5):6246-6263. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su7056246

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerning, Anika, and Chanel Venter. 2015. "Sustainable Supply Chain Engagement in a Retail Environment" Sustainability 7, no. 5: 6246-6263. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/su7056246