Studying the Influence of Nitrogen Deposition, Precipitation, Temperature, and Sunshine in Remotely Sensed Gross Primary Production Response in Switzerland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

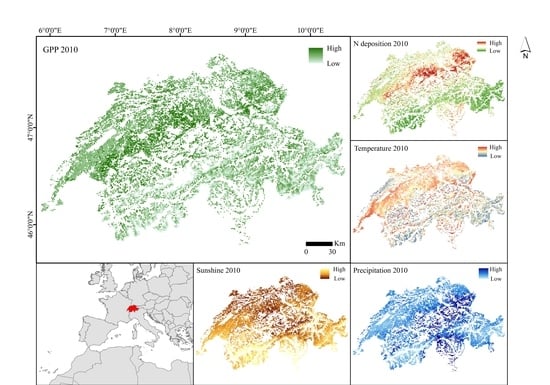

2. Materials and Methods

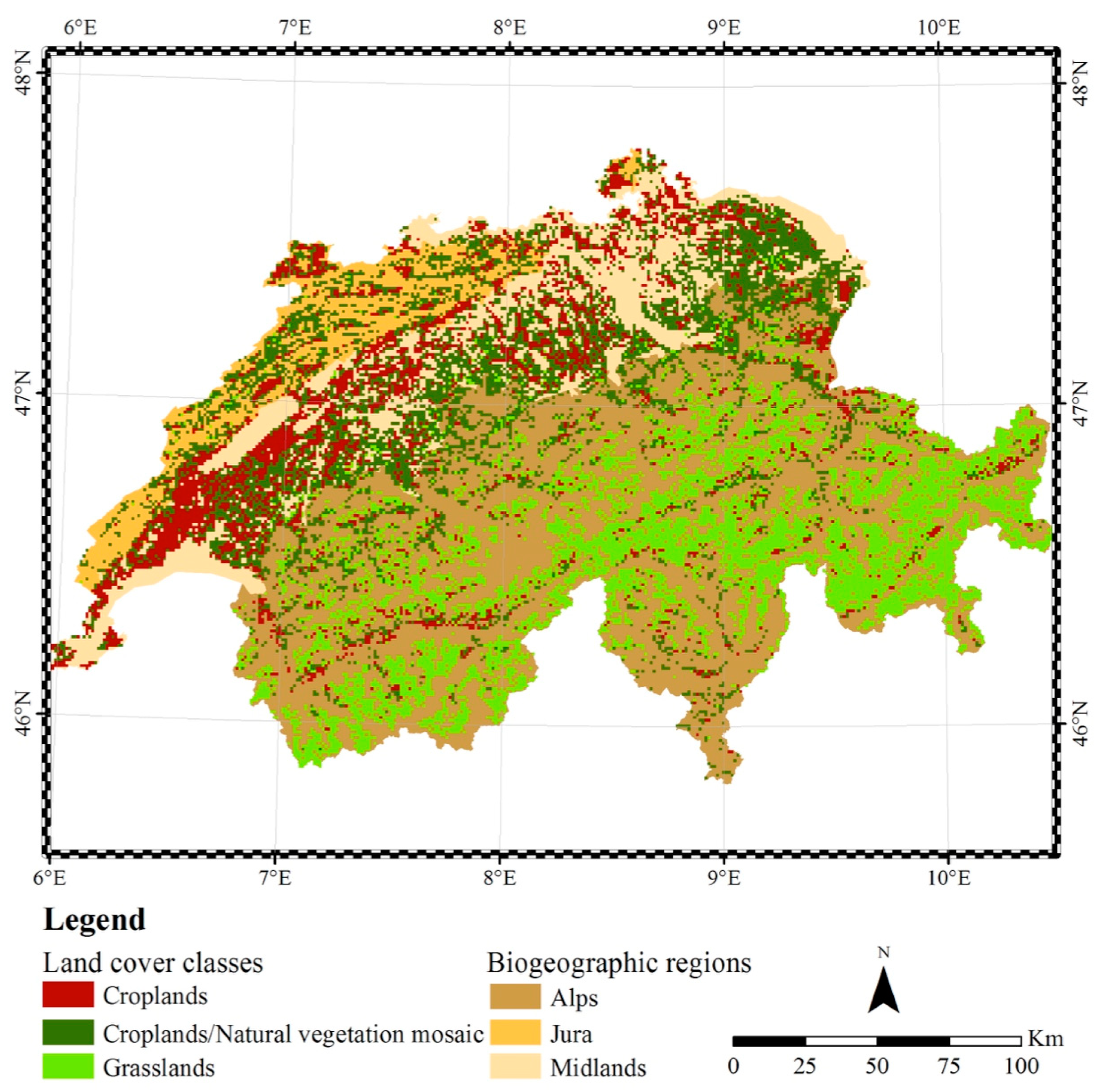

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. MODIS Datasets

2.2.2. N Deposition Datasets

2.2.3. Weather Datasets

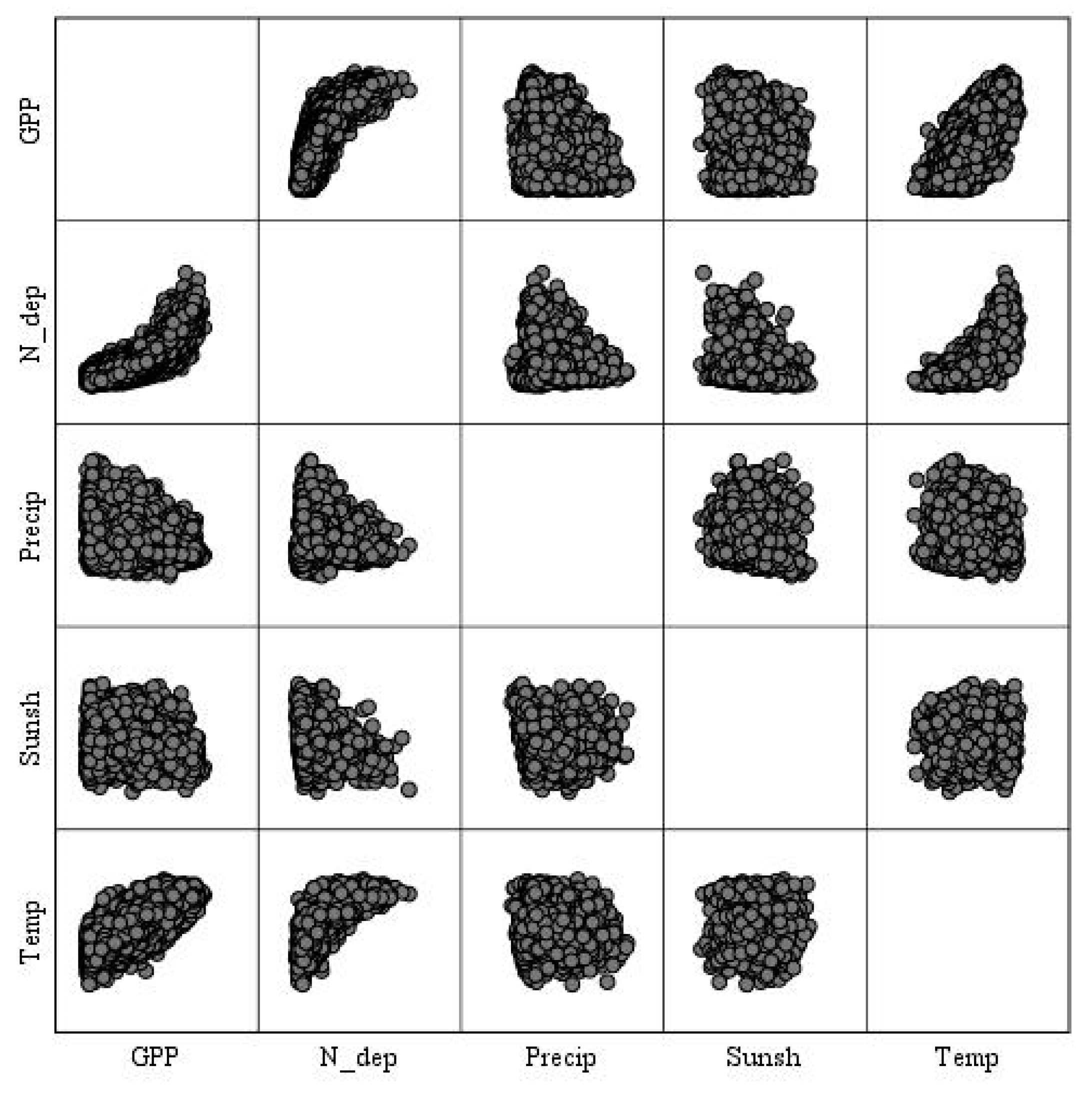

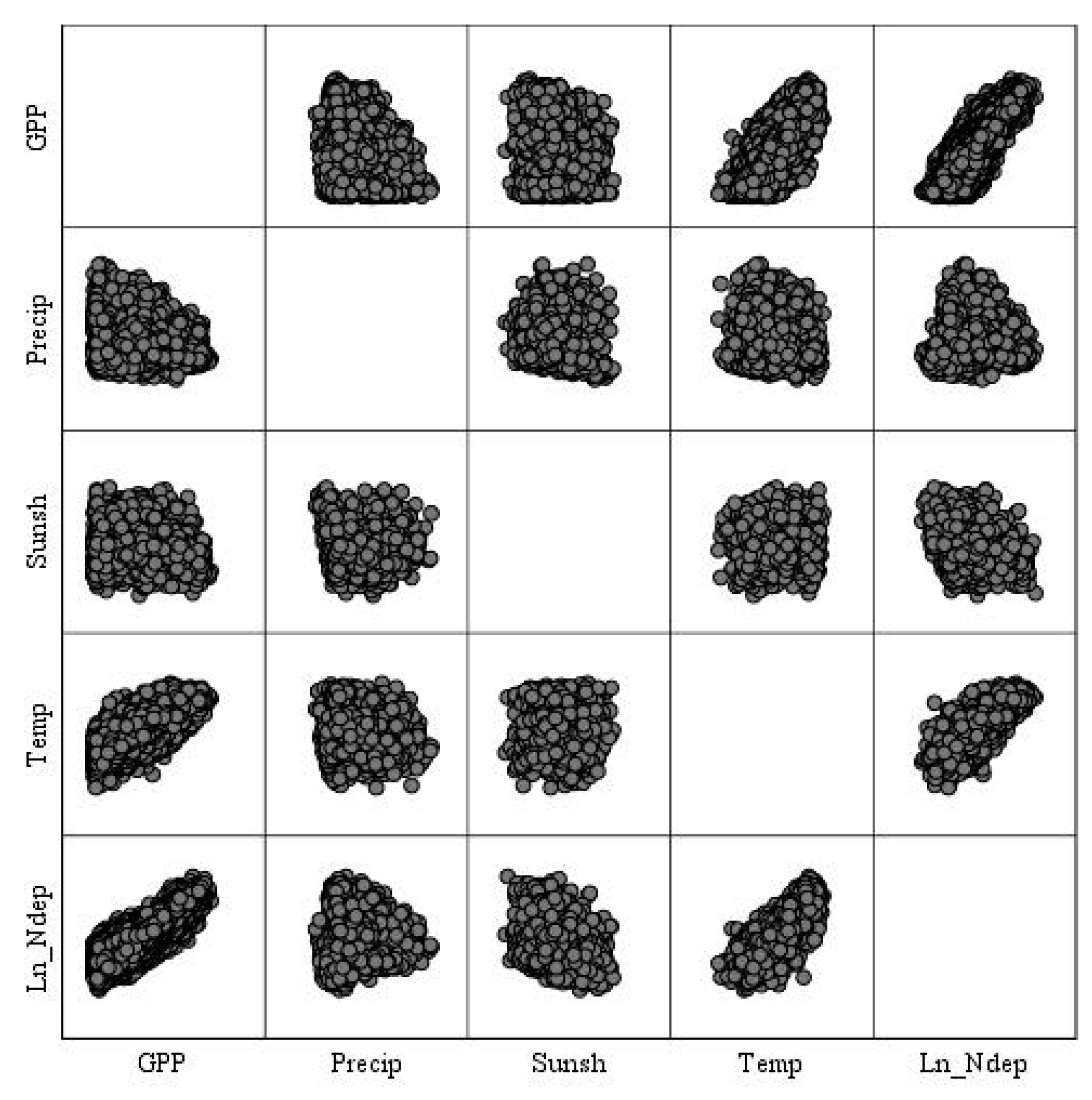

2.3. GPP Response to Limiting Factors Per Land Cover Class: Statistical Analysis

2.4. Soil Characterstics Per Land Cover Class

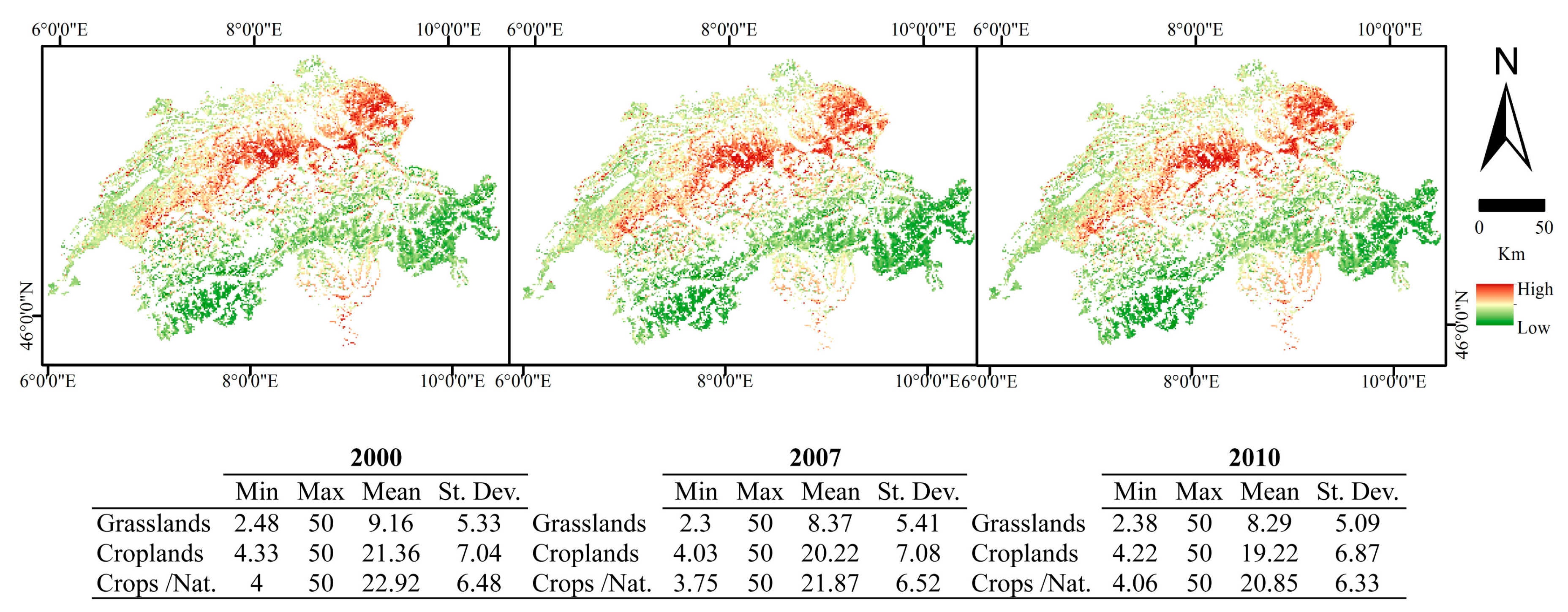

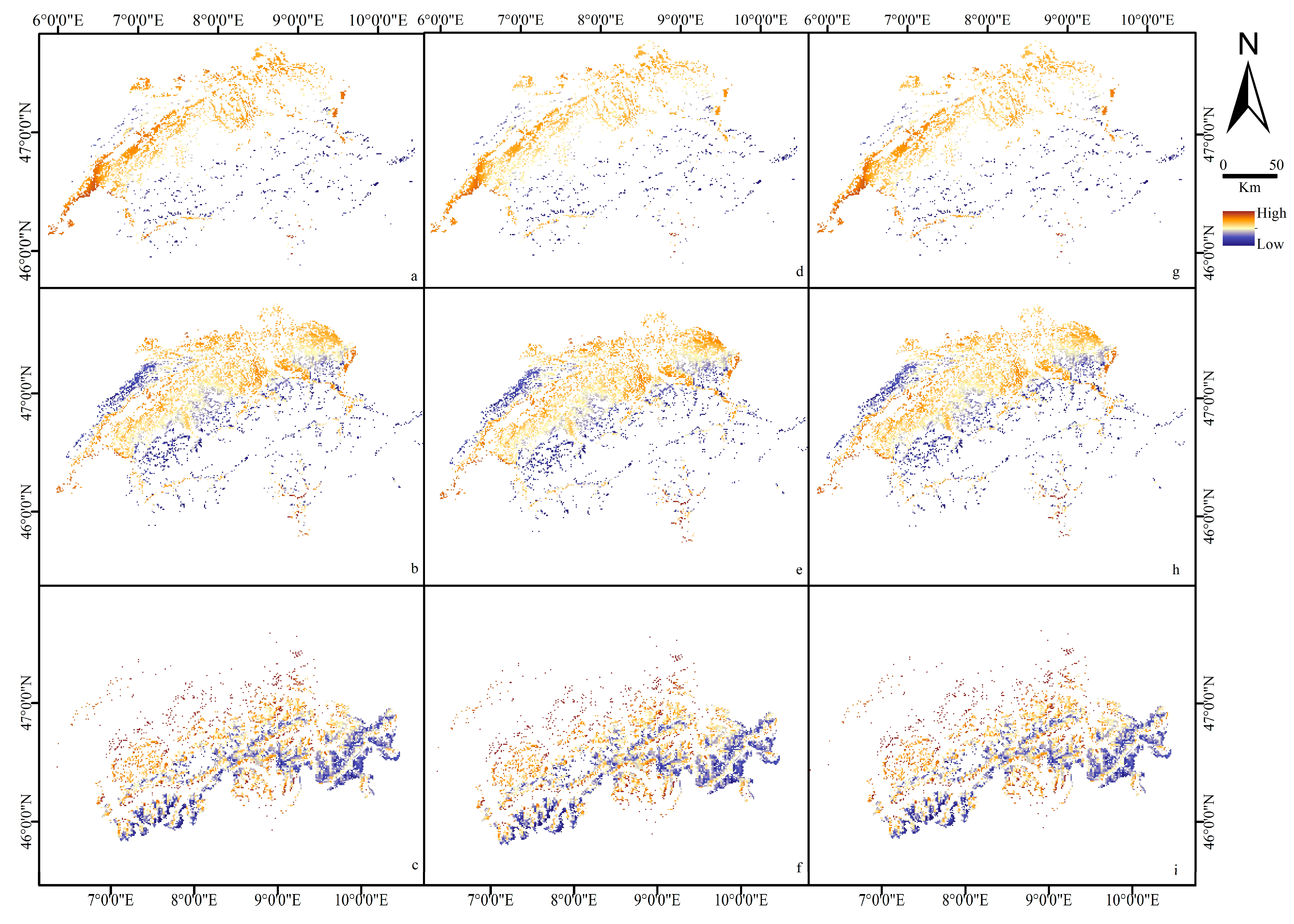

3. Results

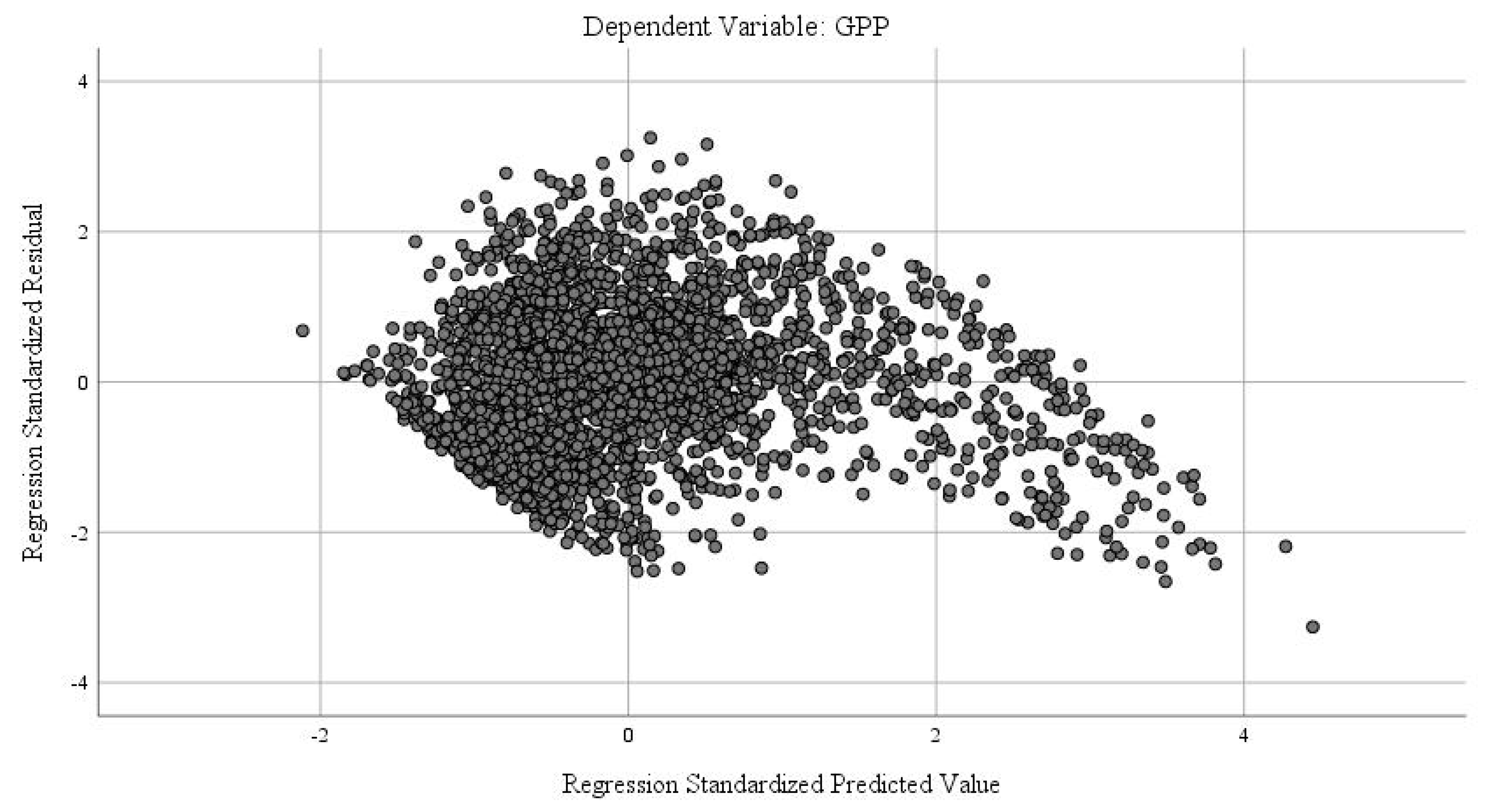

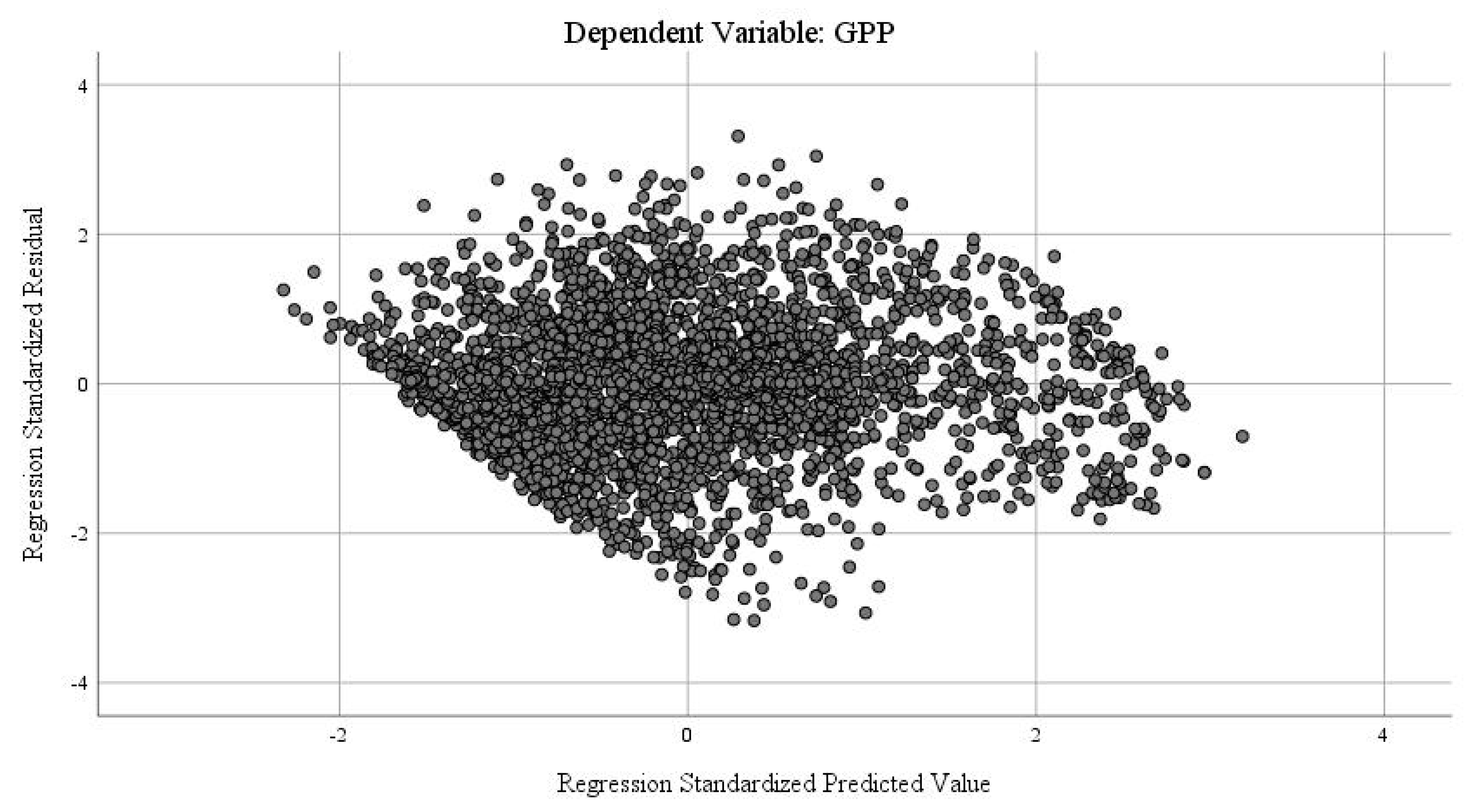

3.1. GPP Response to Limiting Factors Per Land Cover Class: Statistical Analysis

3.2. Soil Characteristics Per Land Cover Class

4. Discussion

GPP Response to Limiting Factors Per Land Cover Class: Statistical Analysis

5. Outlook

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Grasslands | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPP 2000 | GPP 2007 | GPP 2010 | ||||

| Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | |

| Ln N dep | 0.823 ** ± 0.006 | 0.811— 0.833 | 0.798 ** ± 0.006 | 0.786 — 0.811 | 0.813 ** ± 0.006 | 0.801 — 0.824 |

| Temp | 0.741 ** ± 0.008 | 0.724 — 0.756 | 0.749 ** ± 0.008 | 0.734 — 0.763 | 0.748 ** ± 0.008 | 0.733 — 0.763 |

| Precip | −0.220 ** ± 0.016 | −0.250 — −0.190 | 0.059 ** ± 0.017 | 0.026 — 0.092 | −0.035 ** ± 0.017 | −0.069 — −0.001 |

| Sunsh | −0.121 ** ± 0.019 | −0.158 — −0.086 | −0.233 ** ± 0.018 | −0.270 — −0.197 | −0.291 ** ± 0.018 | −0.325 — −0.256 |

| Croplands | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPP 2000 | GPP 2007 | GPP 2010 | ||||

| Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | |

| N dep | 0.664 ** ± 0.011 | 0.643 — 0.687 | 0.615 ** ± 0.013 | 0.590 — 0.640 | 0.588 ** ± 0.013 | 0.560 — 0.616 |

| Temp | 0.527 ** ± 0.015 | 0.499 — 0.554 | 0.487 ** ± 0.016 | 0.455 — 0.518 | 0.477 ** ± 0.016 | 0.445 — 0.508 |

| Precip | −0.383 ** ± 0.018 | −0.418 — −0.347 | −0.164 ** ± 0.023 | −0.208 — −0.115 | −0.236 ** ± 0.021 | −0.276 — −0.195 |

| Sunsh | −0.243 ** ± 0.018 | −0.278 — −0.207 | −0.307 ** ± 0.019 | −0.346 — −0.268 | −0.387 ** ± 0.016 | −0.419 — −0.357 |

| Croplands/Natural Vegetation Mosaic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPP 2000 | GPP 2007 | GPP 2010 | ||||

| Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | Pearson Correlation | 95% CI | |

| N dep | 0.411 ** ± 0.013 | 0.384 — 0.438 | 0.375 ** ± 0.014 | 0.349 — 0.405 | 0.377 ** ± 0.014 | 0.349 — 0.405 |

| Temp | 0.245 ** ± 0.017 | 0.212 — 0.277 | 0.220 ** ± 0.017 | 0.187 — 0.253 | 0.192 ** ± 0.017 | 0.160 — 0.226 |

| Precip | −0.173 ** ± 0.016 | −0.202 — −0.141 | 0.068 ** ± 0.016 | 0.037 — 0.100 | −0.040 * ± 0.016 | −0.074 — −0.008 |

| Sunsh | −0.215 ** ± 0.014 | −0.244 — −0.186 | −0.229 ** ± 0.015 | −0.259 — −0.198 | −0.320 ** ± 0.014 | −0.348 — −0.293 |

References

- Lal, R. Soil Carbon Sequestration Impacts on Global Climate Change and Food Security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S., III; Woodwell, G.M.; Randerson, J.T.; Rastetter, E.B.; Lovett, G.M.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Clark, D.A.; Harmon, M.E.; Schimel, D.S.; Valentini, R.; et al. Reconciling Carbon-Cycle Concepts, Terminology, and Methods. Ecosystems 2006, 9, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anav, A.; Friedlingstein, P.; Beer, C.; Ciais, P.; Harper, A.; Jones, C.; Murray-Tortarolo, G.; Papale, D.; Parazoo, N.C.; Peylin, P.; et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of terrestrial gross primary production: A review. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 785–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monfreda, C.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Farming the planet: 2. Geographic distribution of crop areas, yields, physiological types, and net primary production in the year 2000. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2008, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, G.; Yang, J.; Wimberly, M.C.; Zhang, X.; Tao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, J. Climate-driven global changes in carbon use efficiency. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2014, 23, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, C.; Reichstein, M.; Tomelleri, E.; Ciais, P.; Jung, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Rödenbeck, C.; Arain, M.A.; Baldocchi, D.; Bonan, G.B.; et al. Terrestrial gross carbon dioxide uptake: Global distribution and covariation with climate. Science 2010, 329, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Peylin, P.; MacBean, N.; Ciais, P.; Jia, G.; Ma, M.; Ma, Y.; Shen, M.; et al. Contrasting responses of grassland water and carbon exchanges to climate change between Tibetan Plateau and Inner Mongolia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 249, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, W.W.; Veroustraete, F.; Feyen, J. On temperature and water limitation of net ecosystem productivity: Implementation in the C-Fix model. Ecol. Model. 2006, 199, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J.; Lind, E.M.; Hautier, Y.; Harpole, W.S.; Borer, E.T.; Hobbie, S.; Seabloom, E.W.; Ladwig, L.; Bakker, J.D.; Chu, C.; et al. Anthropogenic nitrogen deposition predicts local grassland primary production worldwide. Ecology 2015, 96, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Volk, M.; Obrist, D.; Novak, K.; Giger, R.; Bassin, S.; Fuhrer, J. Subalpine grassland carbon dioxide fluxes indicate substantial carbon losses under increased nitrogen deposition, but not at elevated ozone concentration. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, W.; Posch, M.; Simpson, D.; Reinds, G.J. Modelling long-term impacts of changes in climate, nitrogen deposition and ozone exposure on carbon sequestration of European forest ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 1097–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Yamamoto, H.; Tani, H.; Zhong, G.; Yin, S.; Guo, E. Spatial pattern of GPP variations in terrestrial ecosystems and its drivers: Climatic factors, CO2 concentration and land-cover change, 1982–2015. Ecol. Inform. 2018, 46, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freibauer, A.; Rounsevell, M.D.A.; Smith, P.; Verhagen, J. Carbon sequestration in the agricultural soils of Europe. Geoderma 2004, 122, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Carbon sequestration in croplands: The potential in Europe and the global context. Eur. J. Agron. 2004, 20, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBauer, D.S.; Treseder, K.K. Nitrogen limitation of net primary productivity in terrestrial ecosystems is globally distributed. Ecology 2008, 89, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, O.E.; Stuart Chapin, F., III; Armesto, J.J.; Berlow, E.; Bloomfield, J.; Dirzo, R.; Huber-Sanwald, E.; Huenneke, L.F.; Jackson, R.B.; Kinzig, A.; et al. Global Biodiversity Scenarios for the Year 2100. Science 2000, 287, 1770–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehri, J.; Schmid, B.; Schaepman-Strub, G.; Niklaus, P.A. Biodiversity promotes primary productivity and growing season lengthening at the landscape scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10160–10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FSO, Agriculture and Forestry. Swiss Agriculture. Pocket Statistics. Federal Statistics Office; Federal Department of Home Affairs: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2015; p. 36. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/agriculture-forestry.assetdetail.349914.html (accessed on 29 May 2017).

- FOAG. Swiss Agricultural Policy; Swiss Federal Office for Agriculture: Liebefeld, Switzerland, 2004; p. 16. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/financial/pes/swiss-pesagriculturalpolicy.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2016).

- Hitz, C.; Egli, M.; Fitze, P. Below-ground and above-ground production of vegetational organic matter along a climosequence in alpine grasslands. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2001, 164, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifeld, J.; Zimmermann, M.; Fuhrer, J.; Conen, F. Storage and turnover of carbon in grassland soils along an elevation gradient in the Swiss Alps. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2009, 15, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassin, S.; Volk, M.; Suter, M.; Buchmann, N.; Fuhrer, J. Nitrogen deposition but not ozone affects productivity and community composition of subalpine grassland after 3 yr of treatment. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bala, G.; Devaraju, N.; Chaturvedi, R.K.; Caldeira, K.; Nemani, R. Nitrogen deposition: How important is it for global terrestrial carbon uptake. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 7147–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaehle, S. Terrestrial nitrogen-carbon cycle interactions at the global scale. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocker, B.D.; Prentice, I.C.; Cornell, S.E.; Davies-Barnard, T.; Finzi, A.C.; Franklin, O.; Janssens, I.; Larmola, T.; Manzoni, S.; Näsholm, T.; et al. Terrestrial nitrogen cycling in Earth system models revisited. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, J.; Ciais, P.; Viovy, N.; Vuichard, N.; Herrero, M.; Havlík, P.; Wang, X.; Sultan, B.; Soussana, J.-F. Effect of climate change, CO2 trends, nitrogen addition, and land-cover and management intensity changes on the carbon balance of European grasslands. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, S.W.; Nemani, R.R.; Heinsch, F.A.; Zhao, M.; Reeves, M.; Hashimoto, H. A continuous satellite-derived measure of global terrestrial primary production. BioScience 2004, 54, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.P.; Ritts, W.D.; Cohen, W.B.; Gower, S.T.; Running, S.W.; Zhao, M.; Costa, M.H.; Kirschbaum, A.A.; Ham, J.M.; Saleska, S.R.; et al. Evaluation of MODIS NPP and GPP products across multiple biomes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 102, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.P.; Ritts, W.D.; Cohen, W.B.; Gower, S.T.; Zhao, M.; Running, S.W.; Wofsy, S.C.; Urbanski, S.; Dunn, A.L.; Munger, J.W. Scaling Gross Primary Production (GPP) over boreal and deciduous forest landscapes in support of MODIS GPP product validation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 88, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, M.; Heinsch, F.A.; Nemani, R.R.; Running, S.W. Improvements of the MODIS terrestrial gross and net primary production global data set. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 95, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Running, S.W.; Nemani, R.R. Sensitivity of Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) terrestrial primary production to the accuracy of meteorological reanalyses. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, D.P.; Ritts, W.D.; Cohen, W.B.; Maeirsperger, T.K.; Gower, S.T.; Kirschbaum, A.A.; Running, S.W.; Zhao, M.; Wofsy, S.C.; Dunn, A.L.; et al. Site-level evaluation of satellite-based global terrestrial gross primary production and net primary production monitoring. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2005, 11, 666–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinsch, F.A.; Zhao, M.; Running, S.W.; Kimball, J.S.; Nemani, R.R.; Davis, K.J.; Bolstad, P.V.; Cook, B.D.; Desai, A.R.; Ricciuto, D.M.; et al. Evaluation of remote sensing based terrestrial productivity from MODIS using regional tower eddy flux network observations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 1908–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, M.A.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Tan, B.; Schneider, A.; Ramankutty, N.; Sibley, A.; Huang, X. MODIS Collection 5 global land cover: Algorithm refinements and characterization of new datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, G.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Q.; Niu, S.; Hu, Z. Covariation between gross primary production and ecosystem respiration across space and the underlying mechanisms: A global synthesis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 203, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solberg, S.; Dobbertin, M.; Reinds, G.J.; Lange, H.; Andreassen, K.; Fernandez, P.G.; Hildingsson, A.; de Vries, W. Analyses of the impact of changes in atmospheric deposition and climate on forest growth in European monitoring plots: A stand growth approach. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 1735–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasoli, S.; Campagnolo, M.; Faria, J.; Nogueira, C.; Da Conceição Caldeira, M. On estimating the gross primary productivity of Mediterranean grasslands under different fertilization regimes using vegetation indices and hyperspectral reflectance. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 5455–5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FOEN. Biogeographic regions of Switzerland (CH); Federal Office for the Environment Federal Office for Environment/Species, Ecosystems, Landscapes Division (FOEN): Ittigen, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://map.geo.admin.ch/?lang=en&topic=bafu&X=190000.00&Y=660000.00&zoom=1&bgLayer=ch.swisstopo.pixelkarte-farbe&catalogNodes=766,767,784,798,804,806,768,781,1361 (accessed on 8 March 2017).

- FSO. Land Use in Switzerland. Results of the Swiss Land Use Statistics; FSO: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2013; p. 24. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/territory-environment.assetdetail.348992.html (accessed on March 2018).

- Gonseth, Y.; Wohlgemuth, T.; Sansonnens, B.; Buttler, A. Les Régions Biogéographiques de la Suisse—Explications et Division Standard; Cahier de l’environnement n° 137. Office fédéral de l’environnement, des forêts et du paysage; OFEFP: Berne, Switzerland, 2001; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Bolliger, J.; Hagedorn, F.; Leifeld, J.; Böhl, J.; Zimmermann, S.; Soliva, R.; Kienast, F. Effects of land-use change on carbon stocks in Switzerland. Ecosystems 2008, 11, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifeld, J.; Bassin, S.; Fuhrer, J. Carbon stocks in Swiss agricultural soils predicted by land-use, soil characteristics, and altitude. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 105, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmann, D.; Herzog, F.; Jeanneret, P.; Konold, W.; Peter, M.; Walter, T.; Wildi, O.; Lüscher, A. Mountain grassland biodiversity: Impact of site conditions versus management type. J. Nat. Conserv. 2008, 16, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, R.; Müller, M.; Korner, P.; Jenny, M.; Jenni, L. 20% loss of unimproved farmland in 22 years in the Engadin, Swiss Alps. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 185, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peringer, A.; Siehoff, S.; Chételat, J.; Spiegelberger, T.; Buttler, A.; Gillet, F. Past and future landscape dynamics in pasture-woodlands of the Swiss Jura Mountains under climate change. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chételat, J.; Kalbermatten, M.; Lannas, K.S.M.; Spiegelberger, T.; Wettstein, J.-B.; Gillet, F.; Peringer, A.; Buttler, A. A Contextual Analysis of Land-Use and Vegetation Changes in Two Wooded Pastures in the Swiss Jura Mountains. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavazov, K.S.; Peringer, A.; Buttler, A.; Gillet, F.; Spiegelberger, T. Dynamics of forage production in pasture-woodlands of the Swiss Jura mountains under projected climate change scenarios. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meteoswiss, Climate of Switzerland. 2014. Available online: http://www.meteoswiss.admin.ch/home/climate/the-climate-of-switzerland.html (accessed on 8 March 2017).

- Meteoswiss, Climate Change in Switzerland. 2015. Available online: http://www.meteoswiss.admin.ch/content/dam/meteoswiss/de/Ungebundene-Seiten/Publikationen/doc/mch_klimawandel_63-13_high.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Running, S.W.; Zhao, M. Gross Primary Productivity 8-Day L4 Global 1Km (MOD17A2), v 5.0 and 5.5 NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC; USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center: Sioux Falls, South Dakota, 2000. Available online: https://lpdaac.usgs.gov (accessed on 16 January 2017).

- Running, S.W.; Zhao, M. User’s Guide Daily GPP and Annual NPP (MOD17A2/A3) Products NASA Earth Observing System MODIS Land Algorithm; NASA MODIS Land Team: Greenbelt, MD, USA.

- Kooistra, L.; Bergsma, A.; Chuma, B.; de Bruin, S. Development of a dynamic web mapping service for vegetation productivity using earth observation and in situ sensors in a sensor web based approach. Sensors 2009, 9, 2371–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskittel, A.R.; Crookston, N.L.; Radtke, P.J. Linking climate, gross primary productivity, and site index across forests of the western United States. Can. J. For. Res. 2011, 41, 1710–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, C.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Q. Spatial-temporal variability of terrestrial vegetation productivity in the Yangtze River Basin during 2000–2009. J. Plant Ecol. 2014, 7, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swisstopo. Digital Height Model, SwissALTI3D; Federal Office of Topography: Köniz, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://shop.swisstopo.admin.ch/de/products/height_models/alti3D (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- FOEN. Nitrogen Deposition. Meteotest and Federal Office of the Environment; Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN): Ittigen, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.bafu.admin.ch/bafu/en/home/topics/air/state/data/historical-data/maps-of-annual-values/map-of-nitrogen-deposition.html (accessed on 2 March 2017).

- FSO. Swiss Land-Use Statistics, ha-grid (Arealstatistik Schweiz); Federal Statistical Office: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2005; Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/raum-umwelt/erhebungen/area.html (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Rihm, B.; Achermann, B. Critical Loads of Nitrogen and Their Exceedances; Swiss Contribution to the Effects-Oriented Work under the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (UNECE); Federal Office for the Environment: Ittigen, Switzerland, 2016; p. 78. Available online: https://www.bafu.admin.ch/bafu/en/home/topics/air/publications-studies/publications/Critical-Loads-of-Nitrogen-and-their-Exceedances.html (accessed on 26 May 2017).

- Thimonier, A.; Kosonen, Z.; Braun, S.; Rihm, B.; Schleppi, P.; Schmitt, M.; Seitler, E.; Waldner, P.; Thöni, L. Total deposition of nitrogen in Swiss forests: Comparison of assessment methods and evaluation of changes over two decades. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 198, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meteoswiss. MeteoSwiss Grid-Data Products; Meteoswiss: Zurich-Airport, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: http://www.meteoswiss.admin.ch/home/climate/swiss-climate-in-detail/monthly-and-annual-maps.html?query=Grid-Data+products (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Meteoswiss. Monthly and Yearly Mean Temperature: TabsM and TabsY; Meteoswiss: Zurich-Airport, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://www.meteoswiss.admin.ch/content/dam/meteoswiss/de/service-und-publikationen/produkt/raeumliche-daten-temperatur/doc/ProdDoc_TabsM.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Meteoswiss. Monthly and Yearly Precipitation: RhiresM and RhiresY; Meteoswiss: Zurich-Airport, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://www.meteoswiss.admin.ch/content/dam/meteoswiss/de/service-und-publikationen/produkt/raeumliche-daten-niederschlag/doc/ProdDoc_RhiresM.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Meteoswiss. Monthly and Yearly Relative Sunshine Duration: SreIM and SrelY; Meteoswiss: Zurich-Airport, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://www.meteoswiss.admin.ch/content/dam/meteoswiss/de/service-und-publikationen/produkt/raeumliche-daten-sonnenschein/doc/ProdDoc_SrelM.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Darlington, R.B.; Hayes, A.F. Regression Analysis and Linear Models: Concepts, Applications, and Implementation; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Linear Regression. In An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 59–126. [Google Scholar]

- Midi, H.; Sarkar, S.K.; Rana, S. Collinearity diagnostics of binary logistic regression model. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2010, 13, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Cai, L. Using heteroskedasticity-consistent standard error estimators in OLS regression: An introduction and software implementation. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- FOAG. Digital Soil Suitability Map of Switzerland; Federal Office for Agriculture (FOAG): Liebefeld, Switzerland, 1980; Available online: https://www.blw.admin.ch/blw/de/home/politik/datenmanagement/geografisches-informationssystem-gis/download-geodaten.html (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Tian, D.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Niu, S. Global evidence on nitrogen saturation of terrestrial ecosystem net primary productivity. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.S.; Pei, J.Y.; Fang, C. Under which climate and soil conditions the plant productivity–precipitation relationship is linear or nonlinear? Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskell, L.C.; Smart, S.M.; Bullock, J.M.; Thompson, K.; Stevens, C.J. Nitrogen deposition causes widespread loss of species richness in British habitats. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2010, 16, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptist, F.; Choler, P. A simulation of the importance of length of growing season and canopy functional properties on the seasonal gross primary production of temperate alpine meadows. Ann. Bot. 2008, 101, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeeman, M.J.; Hiller, R.; Gilgen, A.K.; Michna, P.; Plüss, P.; Buchmann, N.; Eugster, W. Management and climate impacts on net CO2 fluxes and carbon budgets of three grasslands along an elevational gradient in Switzerland. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Giménez, M.; de Jong, R.; Della Peruta, R.; Keller, A.; Schaepman, M.E. Determination of grassland use intensity based on multi-temporal remote sensing data and ecological indicators. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 198, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgard, S.F. Nitrogen cycling in low input legume-based agriculture, with emphasis on legume/grass pastures. Plant Soil 2001, 228, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.; Rigling, A.; Bebi, P.; Brand, F.S.; Briner, S.; Buttler, A.; Elkin, C.; Gillet, F.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Hirschi, C.; et al. Sustainable land use in mountain regions under global change: Synthesis across scales and disciplines. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.J.; Smith, N.G.; Dukes, J.S. Responses of aboveground C and N pools to rainfall variability and nitrogen deposition are mediated by seasonal precipitation and plant community dynamics. Biogeochemistry 2016, 129, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassin, S.; Volk, M.; Fuhrer, J. Species Composition of Subalpine Grassland is Sensitive to Nitrogen Deposition, but Not to Ozone, After Seven Years of Treatment. Ecosystems 2013, 16, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankoughnett, M.R.; Henry, H.A.L. Soil freezing and N deposition: Transient vs multi-year effects on plant productivity and relative species abundance. New Phytol. 2014, 202, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matson, P.; Lohse, K.A.; Hall, S.J. The globalization of nitrogen deposition: Consequences for terrestrial ecosystems. Ambio 2002, 31, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupa, S.V. Effects of atmospheric ammonia (NH3) on terrestrial vegetation: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2003, 124, 179–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, A.K.; Jansson, M. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition has caused nitrogen enrichment and eutrophication of lakes in the northern hemisphere. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2006, 12, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.A.; Alonso, Á. Ecological and toxicological effects of inorganic nitrogen pollution in aquatic ecosystems: A global assessment. Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesterberg, R.; Blatter, A.; Fahrni, M.; Rosset, M.; Neftel, A.; Eugster, W.; Wanner, H. Deposition of nitrogen-containing compounds to an extensively managed grassland in central Switzerland. Environ. Pollut. 1996, 91, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassin, S.; Schalajda, J.; Vogel, A.; Suter, M. Different types of sub-alpine grassland respond similarly to elevated nitrogen deposition in terms of productivity and sedge abundance. J. Veg. Sci. 2012, 23, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Peruta, R.; Keller, A. A regional modelling tool to assess the risk of accumulation of nutrients, trace metals and pesticides in agricultural soils (iMSoil). BGS-Bulletin 37: 9–15. Annèe internationale des Sols—et Maintenant? Pédologie, S.S.D., Ed.; Genève, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: http://www.soil.ch/cms/publikationen/bulletins/bulletin-37/ (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Gómez Giménez, M.; Della Peruta, R.; de Jong, R.; Keller, A.; Schaepman, M.E. Spatial Differentiation of Arable Land and Permanent Grassland to Improve a Land Management Model for Nutrient Balancing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 5655–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliavacca, M.; Reichstein, M.; Richardson, A.D.; Colombo, R.; Sutton, M.A.; Lasslop, G.; Tomelleri, E.; Wohlfahrt, G.; Carvalhais, N.; Cescatti, A.; et al. Semiempirical modeling of abiotic and biotic factors controlling ecosystem respiration across eddy covariance sites. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, M.; Enderle, J.; Bassin, S. Subalpine grassland carbon balance during 7 years of increased atmospheric N deposition. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 3807–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zscheischler, J.; Reichstein, M.; Harmeling, S.; Rammig, A.; Tomelleri, E.; Mahecha, M.D. Extreme events in gross primary production: A characterization across continents. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2909–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaehle, S.; Friend, A.D.; Friedlingstein, P.; Dentener, F.; Peylin, P.; Schulz, M. Carbon and nitrogen cycle dynamics in the O-CN land surface model: 2. Role of the nitrogen cycle in the historical terrestrial carbon balance. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2010, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, B.; Wärlind, D.; Arneth, A.; Hickler, T.; Leadley, P.; Siltberg, J.; Zaehle, S. Implications of incorporating N cycling and N limitations on primary production in an individual-based dynamic vegetation model. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2027–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, R.; Prentice, I.C. Modelling the demand for new nitrogen fixation by terrestrial ecosystems. Biogeosciences 2017, 14, 2003–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Churkina, G.; Zaehle, S.; Hughes, J.; Viovy, N.; Chen, Y.; Jung, M.; Heumann, B.W.; Ramankutty, N.; Heimann, M.; Jones, C. Interactions between nitrogen deposition, land cover conversion, and climate change determine the contemporary carbon balance of Europe. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 2749–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewniak, B.; Gonzalez-Meler, M.A. Earth system model needs for including the interactive representation of nitrogen deposition and drought effects on forested ecosystems. Forests 2017, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Yang, Z.L.; Fisher, J.B.; Zhang, X.; Barlage, M.; Chen, F. Integration of nitrogen dynamics into the Noah-MP land surface model v1.1 for climate and environmental predictions. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGuire, A.D.; Sitch, S.; Clein, J.S.; Dargaville, R.; Esser, G.; Foley, J.; Heimann, M.; Joos, F.; Kaplan, J.; Kicklighter, D.W.; et al. Carbon balance of the terrestrial biosphere in the twentieth century: Analyses of CO2, climate and land use effects with four process-based ecosytem models. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2001, 15, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | 10 | 12 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| n | 2988 | 2066 | 3327 | 2978 | 2074 | 3370 | 2965 | 2074 | 3346 |

| Class | Aptitude for Croplands | StoneContent | Water Storage Capacity | Nutrient Storage Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Very good | Not stony | Extremely low | Extremely low |

| 2 | Good | Slightly stony | Very low | Very low |

| 3 | Medium | Stony | Low | Low |

| 4 | Limited | Very stony | Medium | Medium |

| 5 | Inappropriate | Extremely stony | Good | Good |

| 6 | Unknown | Very good | Very good | |

| 7 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Grasslands | Croplands | Croplands/Natural Vegetation Mosaics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | |

| N deposition | 67.7% | 63.7% | 66.0% | 44.1% | 37.9% | 34.6% | 16.9% | 14.1% | 14.2% |

| Precipitation | 8.1% | 9.5% | 13.6% | 2.7% | Excl. | 5.0% | 2.1% | 1.4% | 1.0% |

| Sunshine | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.2% | Excl. | 0.7% | Excl. | 0.3% | 2.9% |

| Temperature | 0.2% | 1.4% | 0.2% | Excl. | 2.4% | 0.6% | Excl. | 0.5% | Excl. |

| 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE | Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE | Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE |

| Ln N dep | 0.677 *** | 0.225 | Ln N dep | 0.637 *** | 0.246 | Ln N dep | 0.660 *** | 0.220 |

| Precip | 0.759 *** | 0.194 | Precip | 0.731 *** | 0.212 | Precip | 0.796 *** | 0.171 |

| Sunsh | 0.764 *** | 0.192 | Temp | 0.746 *** | 0.206 | Temp | 0.798 *** | 0.170 |

| Temp | 0.766 *** | 0.191 | Sunsh | 0.747 *** | 0.206 | Sunsh | 0.800 *** | 0.169 |

| 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE | Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE | Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE |

| Ln N dep | 0.441 *** | 0.194 | N dep | 0.378 *** | 0.212 | N dep | 0.346 *** | 0.211 |

| Precip | 0.468 *** | 0.190 | Temp | 0.402 *** | 0.207 | Precip | 0.395 *** | 0.203 |

| Sunsh | 0.470 ** | 0.189 | Precip | Excl | Sunsh | 0.402 *** | 0.202 | |

| Temp | Excl | Sunsh | Excl | Temp | 0.408 *** | 0.201 | ||

| 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE | Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE | Order | Adjusted R2 | RMSE |

| N dep | 0.169 *** | 0.228 | N dep | 0.141 *** | 0.247 | N dep | 0.142 *** | 0.238 |

| Precip | 0.189 *** | 0.225 | Temp | 0.146 *** | 0.246 | Sunsh | 0.171 *** | 0.234 |

| Sunsh | Excl | Precip | 0.160 *** | 0.244 | Precip | 0.181 *** | 0.232 | |

| Temp | Excl | Sunsh | 0.163 *** | 0.243 | Temp | Excl | ||

| 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | 95% CI | Coefficients | 95% CI | Coefficients | 95% CI | |

| Const | −0.8075 *** ± 0.0704 | −0.9456 – −0.6695 | 0.1089 ± 0.0971 | −0.0815 – 0.2994 | 0.0783 – 0.0587 | −0.0367 − 0.1934 |

| Ln N dep | 0.6270 *** ± 0.0121 | 0.6033 − 0.6507 | 0.5469 *** ± 0.0136 | 0.5201 − 0.5736 | 0.6095 *** ± 0.0119 | 0.5862 − 0.6329 |

| Precip | −0.0002 *** ± 0.0000 | — | −0.0003 *** ±0.0000 | — | −0.0003 *** ± 0.0000 | — |

| Sunsh | 0.0075 *** ± 0.0013 | 0.0051 − 0.0100 | −0.0057 *** ± 0.0016 | −0.0088 – −0.0026 | −0.0066 *** ± 0.0010 | −0.0086 – −0.0047 |

| Temp | 0.0103 *** ± 0.0018 | 0.0068 ‒ 0.0139 | 0.0279 *** ± 0.0020 | 0.0240 – 0.0319 | 0.0123 *** ± 0.0016 | 0.0091 – 0.0155 |

| 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | 95% CI | Coefficients | 95% CI | Coefficients | 95% CI | |

| Const | -0.1581 ± 0.0783 | -0.3116– -0.0046 | 0.5791 *** ± 0.0123 | 0.5549 – 0.6033 | 1.018 *** ± 0.0540 | 0.9123 – 1.124 |

| N dep | 0.4115 *** ± 0.0114 | 0.3891 – 0.4338 | 0.0197 *** ± 0.0008 | 0.0181 – 0.0212 | 0.0185 *** ± 0.0009 | 0.0168 – 0.0203 |

| Precip | -0.0001 *** ± 0.0000 | — | — | — | -0.0001 *** ± 0.0000 | — |

| Sunsh | 0.004** ± 0.0012 | 0.0017 – 0.0064 | — | — | -0.0062 *** ± 0.0011 | -0.0083 – -0.0042 |

| Temp | — | — | 0.0192 *** ± 0.0017 | 0.0158 ‒ 0.0226 | 0.0104 *** ± 0.0017 | 0.0070 – 0.0138 |

| 2000 | 2007 | 2010 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | 95% CI | Coefficients | 95% CI | Coefficients | 95% CI | |

| Const | 1.077 *** ± 0.0175 | 1.042 – 1.111 | 0.9787 *** ± 0.0643 | 0.8527 – 1.1048 | 1.568 *** ± 0.0478 | 1.475 – 1.662 |

| N dep | 0.0167 *** ± 0.0006 | 0.0154 – 0.0179 | 0.0123 *** ± 0.0008 | 0.0107 – 0.0138 | 0.0138 *** ± 0.0007 | 0.0123 – 0.0152 |

| Precip | -0.0001 *** ± 0.0000 | — | 0.0001 *** ± 0.0000 | — | -0.0001 *** ± 0.0000 | — |

| Sunsh | — | — | -0.0041 *** ± 0.0010 | -0.0061 – -0.0021 | -0.0120 *** ± 0.0010 | -0.0139 – -0.0101 |

| Temp | — | — | 0.0205 *** ± 0.0022 | 0.0161 – 0.0248 | — | — |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gómez Giménez, M.; de Jong, R.; Keller, A.; Rihm, B.; Schaepman, M.E. Studying the Influence of Nitrogen Deposition, Precipitation, Temperature, and Sunshine in Remotely Sensed Gross Primary Production Response in Switzerland. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1135. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rs11091135

Gómez Giménez M, de Jong R, Keller A, Rihm B, Schaepman ME. Studying the Influence of Nitrogen Deposition, Precipitation, Temperature, and Sunshine in Remotely Sensed Gross Primary Production Response in Switzerland. Remote Sensing. 2019; 11(9):1135. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rs11091135

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez Giménez, Marta, Rogier de Jong, Armin Keller, Beat Rihm, and Michael E. Schaepman. 2019. "Studying the Influence of Nitrogen Deposition, Precipitation, Temperature, and Sunshine in Remotely Sensed Gross Primary Production Response in Switzerland" Remote Sensing 11, no. 9: 1135. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rs11091135