Effects of Advertising: A Qualitative Analysis of Young Adults’ Engagement with Social Media About Food

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Online Conversations

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Thematic Analysis

3.2.1. Theme 1: Promotion

“The ads on my social media are tailored to suit what I would like to see, and the internet knows I don’t want to see health ads. I mostly see ads for website creation tools, online stores that I frequent and video games.”(Forum 12: Male, 21 years old)

“Hey Y’all, I also saw the new [Brand name removed] chocolate block—it really grabbed my attention. I think using bright colours will always get people’s attention and I don’t even fancy chocolate that much. I think of myself as ad- impenetrable. I often won’t buy products specifically because they are being advertised”(Forum 3: Male, 22 years old)

“It could be I’ve just grown to tune them out. Oh, something interesting to note also, I do have an adblocker installed, but I turn it off for sites I like (such as facebook and youtube), it’s there purely to protect me from annoying sites or ones which load slowly due to the amount of ads on it.”(Forum 3: Male, 23 years old)

Promotion Strategies That Worked

“As many have already said, the [fast food brand name removed] ad comes to my mind first. The new [fast food product name removed] ad... has come on the many times that my mouth waters and I get the urge to go past [fast food brand name removed] hahaha.”(Forum 3: Female, 20 years old)

“I think this was down to the colours. The ad used pastel colours which made it very easy on the eyes so it was eye catching and pleasant to look at—I wanted to stop and see what the ad was for”(Forum 3: Female, 21 years old)

Promotion Strategies That Were Disliked

“Creating ‘meal deals’ is one of the best things fast food places have done. It makes people feel as though they are getting a good deal, while walking away having spent more money and eating more calories than they initially planned.”(Forum 3: Female, 24 years old)

“I guess that even if it’s annoying, the fact I remember it suggests that it worked. I even shop at [brand name removed], and recognise some of the specials.”(Forum 3: Male, 22 years old)

“It played sometimes 3 times an ad break. Once I saw it back-to-back twice. It was exhausting.”(Forum 3: Female, 24 years old)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Product

“I think it’s easier for food chains (especially the popular ones) to grab our attention because we already know what we’re getting, most of us would have tried their food before and know how delicious it is. so going back for a special deal or to try something new is motivating for us.”(Forum 3: Female, 22 years old)

“I’m trying to eat healthier and all I see is fast food around me. That really makes it difficult to stay motivated and to avoid derailing back into unhealthy takeaway option.”(Forum 3: Female, 18 years old)

“Most of the food ads I get are for fast food or delivery services, and I try to hide them when I see them so that I can avoid temptation!”(Forum 12: Female, 24 years old)

“I have to agree with the [EDNP food brand name removed] ad, that is the only ad I have really taken notice of as well. It’s a little bit disheartening when you think about it that unhealthy foods are the ones that get the spotlight. I’d love to see the 5&2 ads come back!”(Forum 3: Female, 22 years old)

3.2.3. Theme 3: Price

“On a budget as a university student the only ads that catch my attention are either cheap or on a good deal, like ads about [fast food brand name removed], [fast food brand name removed], [fast food brand name removed] etc. I am not particularly happy with my food choices, but eating healthy can’t be achieved by comparatively expensive healthy options to unhealthy ones.”(Forum 3: Male, 19 years old)

“With all the promos and deals that most junk food restaurants offer, they make it seems like a big bargain which sometimes it is, so it makes you want to go out and buy it.”(Forum 3: Male, 21 years old)

“I dislike these [fast food] ads because they are misleading and don’t offer anything positive. Often working class people feel as though these foods are all they can afford, due to dollar menus and $5 meals, however it is consistently shown that whole foods are cheaper in the end.”(Forum 3: Female, 24 years old)

“The marketing they are using is to get people to visit the restaurants, people like myself are unlikely to spend only $3 because we concider this a good deal, it is likely that the more gullible of us (like myself) will spend more money than intended at the restaurant.”(Forum 3: Female, 24 years old)

“Everyday I see this one [food delivery service brand name removed], first time I seen it got me interested for the convenience of the service. Ticked all my boxes healthy, easy, fast and not to much worry about planning.”(Forum 12: Female, 24 years old)

3.2.4. Theme 4: Place

“I’ve seen the 2 fruit 5 veg ad on Facebook multiple times. Definitely something that I find intriguing and occasionally try to do, but not always successfully.”(Forum 12: Male, 23 years old)

“I have recently seen many ads on [fast food brand name removed] mainly on facebook, i find it very annoying i also see it a lot on tv I never really see healthy food ads on tv or in any media i use daily.”(Forum 3: Female, 22 years old)

“One of things I like about advertising on Instagram is that is very non-intrusive. It blends in with the feed very nicely. I believe that ads that are placed in Instagram are generally more reputable mainly because they are often accompanied with abosultely amazing shots of the food. It gives you a reason to like it. Also the fact that it is disguised as a post, instead of an ad is quite nice.”(Forum 3: Male, 23 years old)

“Yes [brand name removed] ads seems to really persuade you. I always get persuaded with the [brand name removed] though. It’s nice to know I can get my donuts near my home instead of driving miles away for it.”(Forum 3: Female, 22 years old)

4. Discussion

4.1. The Marketing Mix

4.2. Advertising on Social Media

4.3. Food Prices and Affordability

4.4. Covert and Overt Advertising

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Implications for Future Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vukmirovic, M. The effects of food advertising on food-related behaviours and perceptions in adults: A review. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenheck, R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: A systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, M.H.; Haghighatdoost, F.; Surkan, P.J.; Azadbakht, L. Associations between dietary energy density and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrition 2016, 32, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.; Nicholas, P.; Supramaniam, R. How much food advertising is there on Australian television? Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kelly, B.; Halford, J.C.; Boyland, E.J.; Chapman, K.; Bautista-Castaño, I.; Berg, C.; Caroli, M.; Cook, B.; Coutinho, J.G.; Effertz, T. Television food advertising to children: A global perspective. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1730–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Ng, S.; Adams, J.; Allemandi, L.; Bahena-Espina, L.; Barquera, S.; Boyland, E.; Calleja, P.; Carmona-Garcés, I.C. Global benchmarking of children’s exposure to television advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages across 22 countries. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smithers, L.G.; Haag, D.G.; Agnew, B.; Lynch, J.; Sorell, M. Food advertising on Australian television: Frequency, duration and monthly pattern of advertising from a commercial network (four channels) for the entire 2016. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 54, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, S.; Freeman, B.; Jones, S. Marketing to Youth in the Digital Age: The Promotion of Unhealthy Products and Health Promoting Behaviours on Social Media. Media Commun. 2016, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.; Kelly, B.; Baur, L.; Chapman, K.; Chapman, S.; Gill, T.; King, L. Digital Junk: Food and Beverage Marketing on Facebook. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e56–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, M.P.; Pauzé, E. The frequency and healthfulness of food and beverages advertised on adolescents’ preferred web sites in Canada. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, M.; Dixon, H.; Wakefield, M. Association between commercial television exposure and fast-food consumption among adults. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boyland, E.J.; Nolan, S.; Kelly, B.; Tudur-Smith, C.; Jones, A.; Halford, J.C.; Robinson, E. Advertising as a cue to consume: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and nonalcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghirad, B.; Duhaney, T.; Motaghipisheh, S.; Campbell, N.; Johnston, B. Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.L.; Graff, S.K. Protecting young people from junk food advertising: Implications of psychological research for First Amendment law. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.; Lobstein, T.; Consortium, P. Regulating the commercial promotion of food to children: A survey of actions worldwide. Int. J. Pediatric Obes. 2011, 6, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.D.; Ronit, K. The EU pledge for responsible marketing of food and beverages to children: Implementation in food companies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, L.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H. Exposure to digital marketing enhances young adults’ interest in energy drinks: An exploratory investigation.(Research Article)(Report). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.; Kelly, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Baur, L. Young adults: Beloved by food and drink marketers and forgotten by public health? Health Promot Int. 2016, 31, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, M.C.; Story, M.; Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Lytle, L.A. Emerging Adulthood and College-aged Youth: An Overlooked Age for Weight-related Behavior Change. Obesity 2008, 16, 2205–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–2018; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Sui, Z.; Wong, W.K.; Louie, J.C.; Rangan, A. Discretionary food and beverage consumption and its association with demographic characteristics, weight status, and fruit and vegetable intakes in Australian adults. Public Health Nutr 2017, 20, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, S.; Mitchell, N.D.; Wells, W.D.; Crawford, R.; Brennan, L.; Spence-Stone, R. Advertising: Principles and Practice; Pearson Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Hosanagar, K.; Nair, H.S. Advertising content and consumer engagement on social media: Evidence from Facebook. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 5105–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shareef, M.A.; Mukerji, B.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Islam, R. Social media marketing: Comparative effect of advertisement sources. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 46, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tuten, T.L.; Solomon, M.R. Social Media Marketing; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Social Marketing Association. Consensus Definition of Social Marketing. 2018. Available online: www.i-socialmarketing.org/social-marketing-definition#.Ww9hMFOFNTY (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Nguyen, D.; Brennan, L.; Parker, L.; Phan-Le, N.T.; Chorazy, E. Social media mechanics and marketing strategy. In Social Marketing and Advertising in the Age of Social Media; Parker, L., Brennan, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhead, S.A.; Hazlett, D.E.; Harrison, L.; Carroll, J.K.; Irwin, A.; Hoving, C. A New Dimension of Health Care: Systematic Review of the Uses, Benefits, and Limitations of Social Media for Health Communication. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sensis. Yellow Social Media Report 2020: Part One Consumers. Available online: https://2k5zke3drtv7fuwec1mzuxgv-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Yellow_Social_Media_Report_2020_Consumer.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- McKinley, C.J.; Wright, P.J. Informational social support and online health information seeking: Examining the association between factors contributing to healthy eating behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Lauckner, C.; Boehmer, J.; Fewins-Bliss, R.; Li, K. Facebooking for health: An examination into the solicitation and effects of health-related social support on social networking sites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2072–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.S.H.; Rouf, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Effectiveness and Behavioral Mechanisms of Social Media Interventions for Positive Nutrition Behaviors in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2018, 63, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutsaert, P.; Regan, Á.; Pieniak, Z.; McConnon, Á.; Moss, A.; Wall, P.; Verbeke, W. The use of social media in food risk and benefit communication. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 30, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaterlaus, J.M.; Patten, E.V.; Roche, C.; Young, J.A. #Gettinghealthy: The perceived influence of social media on young adult health behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Yu, H.; Lu, H.-P. Persuasive messages, popularity cohesion, and message diffusion in social media marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckenstein, M.; Granroth, J. Algorithms, advertising and the intimacy of surveillance. J. Cult. Econ. 2020, 13, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, K.; Fraser, E.M. A Critical Analysis of Attempts to Regulate Native Advertising and Influencer Marketing. Int. J. Commun. 2020, 14, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Wojdynski, B.W.; Evans, N.J. The covert advertising recognition and effects (CARE) model: Processes of persuasion in native advertising and other masked formats. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.; Farley, T.A. Eating as an automatic behavior. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2008, 5, A23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Correa, T.; Reyes, M.; Taillie, L.S.; Corvalán, C.; Dillman Carpentier, F.R. Food advertising on television before and after a national unhealthy food marketing regulation in chile, 2016–2017. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, N. Advertising food to Australian children: Has self-regulation worked? J. Hist. Res. Mark. 2020, 12, 525–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D.; Robinson, L.J.; Dobele, A.R. Word-of-mouth information processing routes: The mediating role of message and source characteristics. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Z.D.; Freimund, W.; Metcalf, E.C.; Nickerson, N.; Powell, R.B. Merging elaboration and the theory of planned behavior to understand bear spray behavior of day hikers in Yellowstone National Park. Environ. Manag. 2019, 63, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986; Volume 19, pp. 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, K.; Borleis, E.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; McCaffrey, T.; Lim, M. What People ‘Like’: Analysis of Social Media Strategies Used by Food Industry Brands, Lifestyle Brands, and Health Promotion Organizations on Facebook and Instagram. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, R.H. Adverse Outcomes Associated With Media Exposure to Contradictory Nutrition Messages. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumasondjaja, S.; Tjiptono, F. Endorsement and visual complexity in food advertising on Instagram. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 659–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.; Corcoran, C.; Tatlow-Golden, M.; Boyland, E.; Rooney, B. See, like, share, remember: Adolescents’ responses to unhealthy-, healthy-and non-food advertising in social media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lombard, C.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; Klassen, K.M.; Palermo, C.; Walker, T.; Lim, M.S.C.; Dean, M.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Truby, H. Communicating health-Optimising young adults’ engagement with health messages using social media: Study protocol. Nutr. Diet 2018, 75, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, L.; Fry, M.-L.; Previte, J. Strengthening social marketing research: Harnessing “insight” through ethnography. Australas. Mark. J. 2015, 23, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pink, S. Digital ethnography. In Innovative Methods in Media and Communication Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VicHealth. Drinking-Related Lifestyles: Exploring the Role of Alcohol in Victorians’ Lives; Victorian Health Promotion Foundation: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Australian Market & Social Research Society. Code of Professional Behaviour; The Australian Market & Social Research Society: Glebe, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3101.0-Australian Demographic Statistics, June 2016. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Previousproducts/3101.0Main%20Features1Jun%202016?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3101.0&issue=Jun%202016&num=&view= (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- International Organization for Standardization. The Facts about Certification. Available online: https://www.iso.org/certification.html (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Klassen, K.; Reid, M.; Brennan, L.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Truby, H.; Lim, M.; Molenaar, A. Methods-Phase 1a Online Conversations Screening and Profiling Surveys and Discussion Guide; Monash University Workflow: Melbourne, Austalia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological; Maerican Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L.; Brennan, L. Social Marketing and Advertising in the Age of Social Media; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides, E. The marketing mix revisited: Towards the 21st century marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2006, 22, 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, W.D. How social marketing works in health care. BMJ 2006, 332, 1207–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapetanaki, A.; Brennan, D.; Caraher, M. Social marketing and healthy eating: Findings from young people in Greece. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2014, 11, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stead, M.; Hastings, G.; McDermott, L. The meaning, effectiveness and future of social marketing. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carins, J.E.; Rundle-Thiele, S.R. Eating for the better: A social marketing review (2000–2012). Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vedel, I.; Ramaprasad, J.; Lapointe, L. Social Media Strategies for Health Promotion by Nonprofit Organizations: Multiple Case Study Design. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, L.; Buijzen, M. Craving healthy foods?! How sensory appeals increase appetitive motivational processing of healthy foods in adolescents. Media Psychol. 2020, 23, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, M.; Hasson, M.; Duell, B. Internet Advertising. Available online: https://www.pwc.com.au/industry/entertainment-and-media-trends-analysis/outlook/2018/internet-advertising.html (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Yoon, S.; Bang, H.; Choi, D.; Kim, K. Slow versus fast: How speed-induced construal affects perceptions of advertising messages. Int. J. Advert. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycki, N. Reach vs. Impressions: What’s the Difference (And What Should You Track)? Available online: https://blog.hootsuite.com/reach-vs-impressions/ (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Gunter, B. Food Advertising: Informative, Misleading or Deceptive? In Food Advertising: Nature, Impact and Regulation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 109–146. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear, V.A.; Armour, K.M.; Wood, H. Young people and their engagement with health-related social media: New perspectives. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, H.; Lam, T.; Pettigrew, S.; Tait, R. Alcohol marketing on YouTube: Exploratory analysis of content adaptation to enhance user engagement in different national contexts. BMC Public Health 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorveld, H.A.M.; van Noort, G. Social Media in Advertising Campaigns:Examining the Effects on Perceived Persuasive Intent, Campaign and Brand Responses. J. Creat. Commun. 2014, 9, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buchanan, L.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H.; Kariippanon, K. The effects of digital marketing of unhealthy commodities on young people: A systematic review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obesity Policy Coalition. Policy Brief: Food Advertising Regulation in Australia. Available online: https://www.opc.org.au/downloads/policy-briefs/food-advertising-regulation-in-australia.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Molenaar, A.; Choi, T.S.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; Lim, M.S.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. Language of Health of Young Australian Adults: A Qualitative Exploration of Perceptions of Health, Wellbeing and Health Promotion via Online Conversations. Nutrients 2020, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henley, N. The application of marketing principles to a social marketing campaign. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2011, 29, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S. Pleasure: An under-utilised ‘P’ in social marketing for healthy eating. Appetite 2016, 104, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunseit, A.C.; Cook, A.S.; Conti, J.; Gwizd, M.; Allman-Farinelli, M. “Doing a good thing for myself”: A qualitative study of young adults’ strategies for reducing takeaway food consumption. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deliens, T.; Clarys, P.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B. Determinants of eating behaviour in university students: A qualitative study using focus group discussions. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munt, A.E.; Partridge, S.R.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The barriers and enablers of healthy eating among young adults: A missing piece of the obesity puzzle: A scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Harker, M.; Harker, D.; Reinhard, K. Youth transition to university in Germany and Australia: An empirical investigation of healthy eating behaviour. J. Youth Stud. 2010, 13, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooksey-Stowers, K.; Schwartz, M.B.; Brownell, K.D. Food swamps predict obesity rates better than food deserts in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Testa, A.; Jackson, D.B.; Semenza, D.C.; Vaughn, M.G. Food deserts and cardiovascular health among young adults. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, H.; Baggett, A.; Grigor, J. Adolescent and young adult perceptions of caffeinated energy drinks. A qualitative approach. Appetite 2013, 65, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnwald, B.P.; Handley-Miner, I.J.; Samuels, N.A.; Markus, H.R.; Crum, A.J. Nutritional Analysis of Foods and Beverages Depicted in Top-Grossing US Movies, 1994-2018. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Klassen, K.; Weng, E.; Chin, S.; Molenaar, A.; Reid, M.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. A social marketing perspective of young adults’ concepts of eating for health: Is it a question of morality? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Institute of Family Studies. Young People Living with Their Parents. Available online: https://aifs.gov.au/facts-and-figures/young-people-living-their-parents (accessed on 2 November 2020).

| Forum | Discussion Guide | Logic of Inquiry |

|---|---|---|

| Forum 3: Ads about food | Over the course of this online community, let’s post here all the food related ads that we’ve noticed online over the recent weeks or that we’re noticing now and let’s discuss what caught our attention, what we like and don’t like... For any ad that is posted here by another member, please comment too and share whether you had noticed it before, what you like and don’t like. | Objective: Identify impactful food industry campaigns including triggers for engagement |

| Forum 12: The health ads we notice | Can you remember any health-related ads you’ve seen on social media? Let’s post all the health-related ads, articles, slogans, or anything that we noticed lately and discuss what comes to mind when we see these. Photos, links, screen grabs are all welcome. | Objective: Uncover triggers of interest |

| Variable | Category | N Participants (% of Total) or Median (25th, 75th Percentile) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender identity | Female | 101 (60.8%) |

| Male | 64 (38.6%) | |

| Non-binary/genderfluid/genderqueer | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Age (years) | 21 (19, 23) | |

| 18–21 | 92 (55.4%) | |

| 22–24 | 74 (44.6%) | |

| Location type * | Metro | 133 (80.1%) |

| Regional | 33 (19.9%) | |

| Language spoken at home | English | 124 (74.7%) |

| Language other than English | 42 (25.3%) | |

| Living arrangements † | Living with parents | 80 (48.2%) |

| My partner | 35 (21.1%) | |

| Friend(s)/housemate(s) | 28 (16.9%) | |

| Alone | 19 (11.4%) | |

| Living with own child(ren) | 17 (10.2%) | |

| Other family | 17 (10.2%) | |

| Dispensable weekly income ‡ | Less than AUD 40 | 65 (39.2%) |

| AUD 40–79 | 48 (28.9%) | |

| AUD 80–119 | 29 (17.5%) | |

| AUD 120–199 | 11 (6.6%) | |

| AUD 200–299 | 9 (5.4%) | |

| AUD 300 or over | 3 (1.8%) | |

| I don’t wish to say | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Currently studying | Yes | 111 (66.9%) |

| No | 55 (33.1%) | |

| Level of current study (only completed by those who said they were currently studying) | High school, year 12 | 8 (4.8%) |

| TAFE, college, or diploma | 13 (7.8%) | |

| University (undergraduate course) | 80 (48.2%) | |

| University (postgraduate course) | 10 (6.0%) | |

| Highest level of education completed (only completed by those who said they were not currently studying) | High school, year 10 or lower | 1 (0.6%) |

| High school, year 11 | 2 (1.2%) | |

| High school, year 12 | 12 (7.2%) | |

| TAFE, college, or diploma | 23 (13.9%) | |

| University (undergraduate course) | 15 (9.0%) | |

| University (postgraduate course) | 2 (1.2%) | |

| Main cultural identity | Caucasian (e.g., Australian, European) | 130 (78.3%) |

| East and South Asian (e.g., Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese) | 20 (12.0%) | |

| West Asian and Middle Eastern (e.g., Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan) | 10 (6.0%) | |

| Aboriginal Australian | 4 (2.4%) | |

| New Zealander | 2 (1.2%) | |

| Body mass index kg/m2 (calculated from self-reported height and weight) | 23.8 (20.4, 27.5) | |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) | 17 (10.2%) | |

| Healthy weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 88 (53.0%) | |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 36 (21.7%) | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) | 25 (15.1%) |

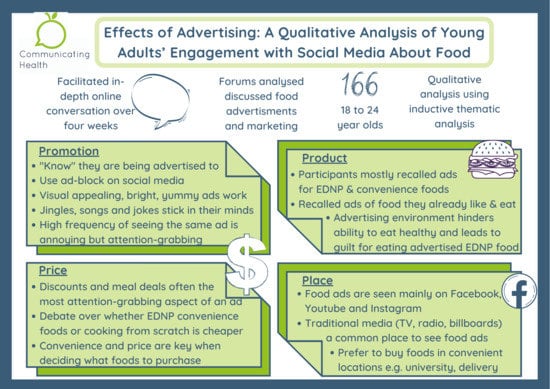

| Theme | Summary |

|---|---|

| Theme 1—Promotion | These young adults “knew” they were being advertised to both online and in traditional media. Many participants utilised ad-blocking applications on social media to block out unwanted marketing. Advertisements that caught their attention were often visually appealing, bright, and included “yummy” energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods. Jingles, songs, and jokes stuck in the minds of these young adults. Seeing the same advertisement often was annoying but attention-grabbing and memorable. |

| Theme 2—Product | Participants mostly recalled advertisements for energy-dense, nutrient-poor and convenience foods. Advertisements for foods that the young adults already like and eat were attention-grabbing and memorable. Participants felt the advertising environment both online and in real-life hindered their ability to eat healthy and led to feelings of guilt when they were “tempted” by the unhealthy food advertised. |

| Theme 3—Price | Discounts and meal deals were one of the most attention-grabbing aspects of a food advertisement. Among participants, there were differing opinions over which was more expensive, energy-dense, nutrient-poor food convenience foods or cooking whole foods from scratch. When deciding which foods to purchase, convenience and price were key. |

| Theme 4—Place | Food advertisements were mainly seen on Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram. Traditional media (television, radio, and billboards) were a common place for young adults to see food advertisements. Participants preferred to buy foods in locations convenient to them, for example, at university or through food delivery. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molenaar, A.; Saw, W.Y.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; Lim, M.S.C.; McCaffrey, T.A. Effects of Advertising: A Qualitative Analysis of Young Adults’ Engagement with Social Media About Food. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1934. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nu13061934

Molenaar A, Saw WY, Brennan L, Reid M, Lim MSC, McCaffrey TA. Effects of Advertising: A Qualitative Analysis of Young Adults’ Engagement with Social Media About Food. Nutrients. 2021; 13(6):1934. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nu13061934

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolenaar, Annika, Wei Yee Saw, Linda Brennan, Mike Reid, Megan S. C. Lim, and Tracy A. McCaffrey. 2021. "Effects of Advertising: A Qualitative Analysis of Young Adults’ Engagement with Social Media About Food" Nutrients 13, no. 6: 1934. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nu13061934