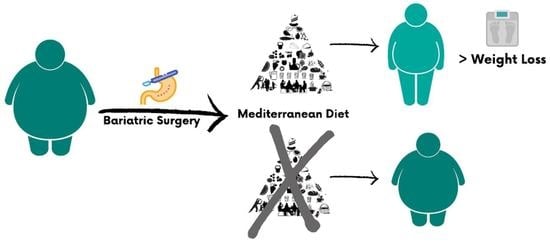

Clinical Impact of Mediterranean Diet Adherence before and after Bariatric Surgery: A Narrative Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Study Eligibility and Selection

3. Results

3.1. Mediterranean Diet Adherence before Bariatric Surgery

3.2. Mediterranean Diet Adherence after Bariatric Surgery

3.3. Long Term Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ming Fock, K.; Khoo, J. Diet and Exercise in Management of Obesity and Overweight. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 28 (Suppl. S4), 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galani, C.; Schneider, H. Prevention and Treatment of Obesity with Lifestyle Interventions: Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2008, 52, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chooi, Y.C.; Ding, C.; Magkos, F. The Epidemiology of Obesity. Metabolism 2019, 92, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11234459/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Kelly, T.; Yang, W.; Chen, C.S.; Reynolds, K.; He, J. Global Burden of Obesity in 2005 and Projections to 2030. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gulliford, M.C.; Charlton, J.; Prevost, T.; Booth, H.; Fildes, A.; Ashworth, M.; Littlejohns, P.; Reddy, M.; Khan, O.; Rudisill, C. Costs and Outcomes of Increasing Access to Bariatric Surgery: Cohort Study and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Using Electronic Health Records. Value Health 2017, 20, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Welbourn, R.; Hollyman, M.; Kinsman, R.; Dixon, J.; Liem, R.; Ottosson, J.; Ramos, A.; Våge, V.; Al-Sabah, S.; Brown, W.; et al. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide: Baseline Demographic Description and One-Year Outcomes from the Fourth IFSO Global Registry Report 2018. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perrone, F.; Bianciardi, E.; Ippoliti, S.; Nardella, J.; Fabi, F.; Gentileschi, P. Long-Term Effects of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy versus Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass for the Treatment of Morbid Obesity: A Monocentric Prospective Study with Minimum Follow-Up of 5 Years. Updat. Surg. 2017, 69, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wissen, J.; Bakker, N.; Doodeman, H.J.; Jansma, E.P.; Bonjer, H.J.; Houdijk, A.P.J. Preoperative Methods to Reduce Liver Volume in Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review. Obes Surg. 2016, 26, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sjöström, L.; Lindroos, A.-K.; Peltonen, M.; Torgerson, J.; Bouchard, C.; Carlsson, B.; Dahlgren, S.; Larsson, B.; Narbro, K.; Sjöström, C.D.; et al. Lifestyle, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors 10 Years after Bariatric Surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 351, 2683–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ansari, W.; Elhag, W. Weight Regain and Insufficient Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery: Definitions, Prevalence, Mechanisms, Predictors, Prevention and Management Strategies, and Knowledge Gaps—A Scoping Review. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadena-Obando, D.; Ramírez-Rentería, C.; Ferreira-Hermosillo, A.; Albarrán-Sanchez, A.; Sosa-Eroza, E.; Molina-Ayala, M.; Espinosa-Cárdenas, E. Are There Really Any Predictive Factors for a Successful Weight Loss after Bariatric Surgery? BMC Endocr. Disord. 2020, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ros, E.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Fitó, M.; Martínez, J.A.; Corella, D. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health: Teachings of the PREDIMED Study. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 330S–336S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; Corella, D.; Fitó, M.; Ros, E. Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Insights from the PREDIMED Study. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 58, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean Diet and Health: A Comprehensive Overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Dieta Mediterránea. Available online: https://dietamediterranea.com (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Schiavo, L.; Scalera, G.; Sergio, R.; De Sena, G.; Pilone, V.; Barbarisi, A. Clinical Impact of Mediterranean-Enriched-Protein Diet on Liver Size, Visceral Fat, Fat Mass, and Fat-Free Mass in Patients Undergoing Sleeve Gastrectomy. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015, 11, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Tovar, J.; Boix, E.; Bozhychko, M.; Del Campo, J.M.; Martínez, R.; Bonete, J.M.; Calpena, R. Adherencia Pre y Postoperatoria a La Dieta Mediterránea y Su Efecto Sobre La Pérdida de Peso y El Perfil Lipídico En Pacientes Obesos Mórbidos Sometidos a Gastrectomía Vertical Como Procedimiento Bariátrico. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 30, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gils Contreras, A.; Bonada Sanjaume, A.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet or Physical Activity After Bariatric Surgery and Its Effects on Weight Loss, Quality of Life, and Food Tolerance. Obes. Surg. 2019, 30, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, L.; Di Rosa, M.; Tramontano, S.; Rossetti, G.; Iannelli, A.; Pilone, V. Long-Term Results of the Mediterranean Diet after Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 3792–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Tovar, J.; Boix, E.; Bonete, J.M.; Martínez, R.; Zubiaga, L.; Díez, M.; Calpena, R.; Remedios Alpera, M.; Aroyo, A.; Miranda, E.; et al. Effect of Preoperative Eating Patterns and Preoperative Weight Loss on the Short- and Mid-Term Weight Loss Results of Sleeve Gastrectomy. Cir. Esp. 2015, 93, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamanos, B.; Thanopoulou, A.; Angelico, F.; Assaad-Khalil, S.; Barbato, A.; Del Ben, M.; Dimitrijevic-Sreckovic, V.; Djordjevic, P.; Gallotti, C.; Katsilambros, N.; et al. Nutritional Habits in the Mediterranean Basin. The Macronutrient Composition of Diet and Its Relation with the Traditional Mediterranean Diet. Multi-Centre Study of the Mediterranean Group for the Study of Diabetes (MGSD). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, A.; De Pergola, G. Mediterranean Diet Pyramid: A Proposal for Italian People. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4302–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Padwal, R.; Klarenbach, S.; Wiebe, N.; Birch, D.; Karmali, S.; Manns, B.; Hazel, M.; Sharma, A.M.; Tonelli, M. Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 602–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.H.; Stoll, C.R.T.; Song, J.; Varela, J.E.; Eagon, C.J.; Colditz, G.A. The Effectiveness and Risks of Bariatric Surgery: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, 2003–2012. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buchwald, H.; Avidor, Y.; Braunwald, E.; Jensen, M.D.; Pories, W.; Fahrbach, K.; Schoelles, K. Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2004, 292, 1724–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, E.C.; Heineck, I.; Athaydes, G.; Meinhardt, N.G.; Souto, K.E.P.; Stein, A.T. Is Bariatric Surgery Effective in Reducing Comorbidities and Drug Costs? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Surg. 2015, 25, 1741–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, J.G.; Filion, K.B.; Atallah, R.; Eisenberg, M.J. Systematic Review of the Mediterranean Diet for Long-Term Weight Loss. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, 407–415.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papadaki, A.; Nolen-Doerr, E.; Mantzoros, C.S. The Effect of the Mediterranean Diet on Metabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials in Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, K.; Kastorini, C.M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Giugliano, D. Mediterranean Diet and Weight Loss: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2011, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.-I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Salvadó, J.; Bulló, M.; Babio, N.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Ibarrola-Jurado, N.; Basora, J.; Estruch, R.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; et al. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes With the Mediterranean Diet. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velapati, S.R.; Shah, M.; Kuchkuntla, A.R.; Abu-dayyeh, B.; Grothe, K.; Hurt, R.T.; Mundi, M.S. Weight Regain After Bariatric Surgery: Prevalence, Etiology, and Treatment. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2018, 7, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmali, S.; Brar, B.; Shi, X.; Sharma, A.M.; De Gara, C.; Birch, D.W. Weight Recidivism Post-Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review. Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 1922–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, C.; Kapoor, H.C. Antioxidants in Fruits and Vegetables—The Millennium’s Health. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 36, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.L.; Lloyd, B. Health Benefits of Fruits and Vegetables. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whigham, L.D.; Valentine, A.R.; Johnson, L.K.; Zhang, Z.; Atkinson, R.L.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. Increased Vegetable and Fruit Consumption during Weight Loss Effort Correlates with Increased Weight and Fat Loss. Nutr. Diabetes 2012, 2, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruanpeng, D.; Thongprayoon, C.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Harindhanavudhi, T. Sugar and Artificially Sweetened Beverages Linked to Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. QJM Int. J. Med. 2017, 110, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bianciardi, E.; Fabbricatore, M.; Lorenzo, G.D.I.; Innamorati, M.; Tomassini, L.; Gentileschi, P.; Niolu, C.; Siracusano, A.; Imperatori, C. Prevalence of Food Addiction and Binge Eating in an Italian Sample of Bariatric Surgery Candidates and Overweight/Obese Patients Seeking Low-Energy-Diet Therapy. Riv. Psichiatr. 2019, 54, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo Fernández, M.; Marset, J.B.; Lesmes, I.B.; Izquierdo, J.Q.; Sala, X.F.; Salas-Salvadó, J. FESNAD-SEEDO Consensus Summary: Evidence-Based Nutritional Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Endocrinol. Nutr. 2012, 59, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ansari, W.; El-Ansari, K. Missing Something? Comparisons of Effectiveness and Outcomes of Bariatric Surgery Procedures and Their Preferred Reporting: Refining the Evidence Base. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 3167–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, M.; Bellia, A.; Mattiuzzo, F.; Franchi, A.; Ferri, C.; Padua, E.; Guglielmi, V.; D’Adamo, M.; Annino, G.; Gentileschi, P.; et al. Frequent Follow-Up Visits Reduce Weight Regain in Long-Term Management After Bariatric Surgery. Bariatr. Surg. Pract. Patient Care 2015, 10, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Year | Study Design | Number of Participants | Follow-Up (Years) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schiavo et al. [17] | 2015 | descriptive prospective cohort | 37 | -- | Participants who adhered to a MD 1 showed significant decreases in weight, liver size, visceral fat, and fat mass before undergoing BS 2. |

| Ruiz-Tovar et al. [18] | 2014 | prospective observational study | 50 | 1 | Better adherence to a MD resulted in greater weight loss, and improved lipid profiles after BS. |

| Contreras et al. [19] | 2020 | prospective observational study | 78 | 1 | Increased adherence to a MD resulted in greater weight loss after BS. |

| Schiavo et al. [20] | 2020 | prospective observational study | 74 | 4 | Patients who underwent BS were found to have an inadequate MD adherence after at least 4 years of intervention, with weight regain in 37.8% of patients. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gastaldo, I.; Casas, R.; Moizé, V. Clinical Impact of Mediterranean Diet Adherence before and after Bariatric Surgery: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 393. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nu14020393

Gastaldo I, Casas R, Moizé V. Clinical Impact of Mediterranean Diet Adherence before and after Bariatric Surgery: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2022; 14(2):393. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nu14020393

Chicago/Turabian StyleGastaldo, Isabella, Rosa Casas, and Violeta Moizé. 2022. "Clinical Impact of Mediterranean Diet Adherence before and after Bariatric Surgery: A Narrative Review" Nutrients 14, no. 2: 393. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/nu14020393