Biosynthesis of Pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde via Enzymatic CO2 Fixation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

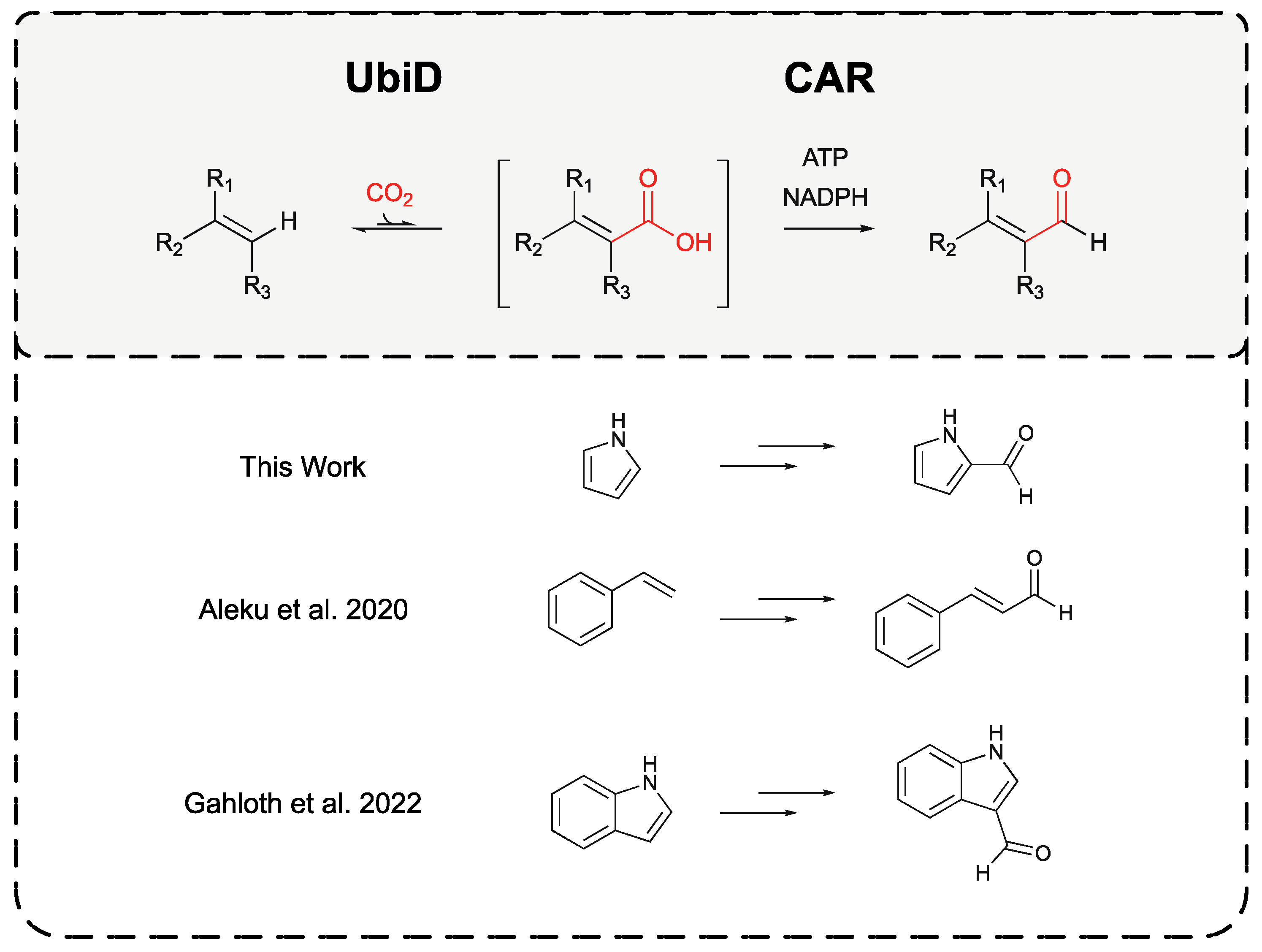

2. Results and Discussion

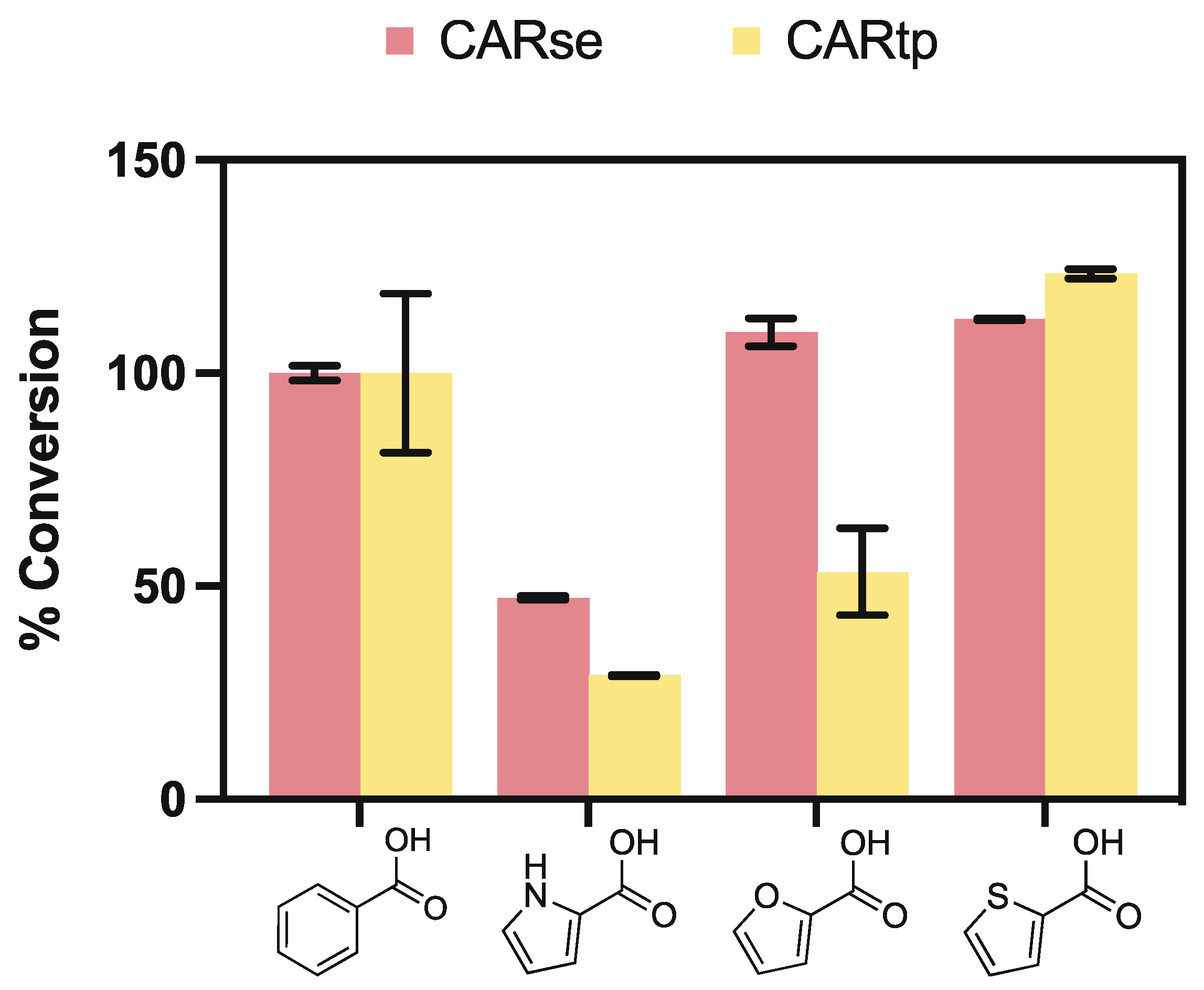

2.1. Screening of Carboxylic Acid Reductases for Activity towards Five-Membered Heterocyclic Carboxylic Acids

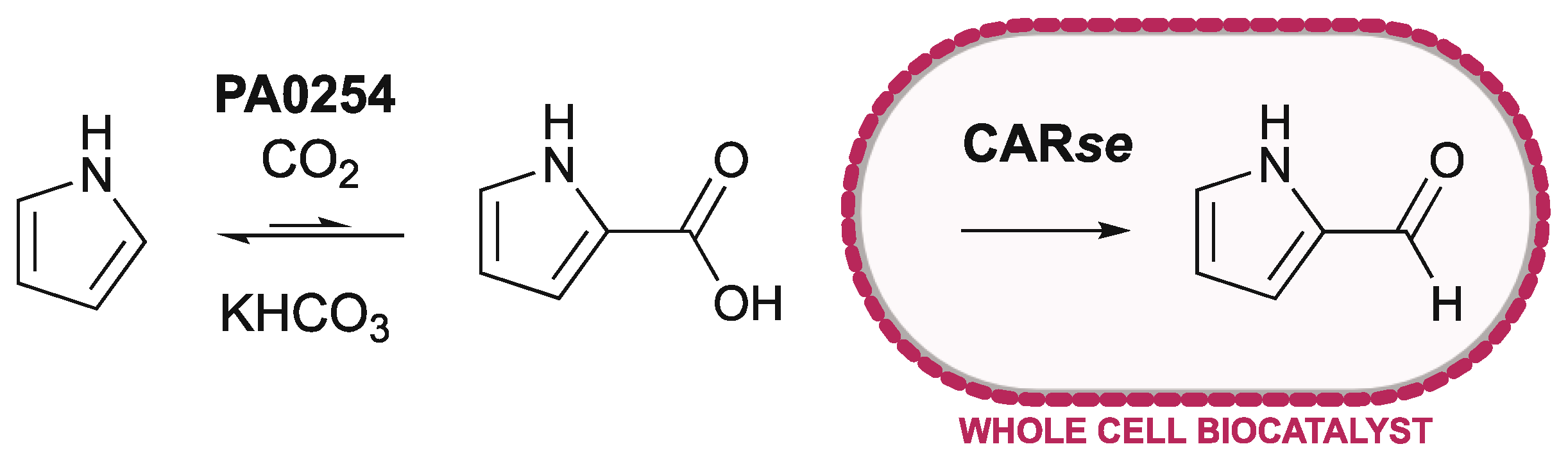

2.2. Coupling of Purified PA0254 and CARse

2.3. Using Whole-Cell CARse Biocatalysts

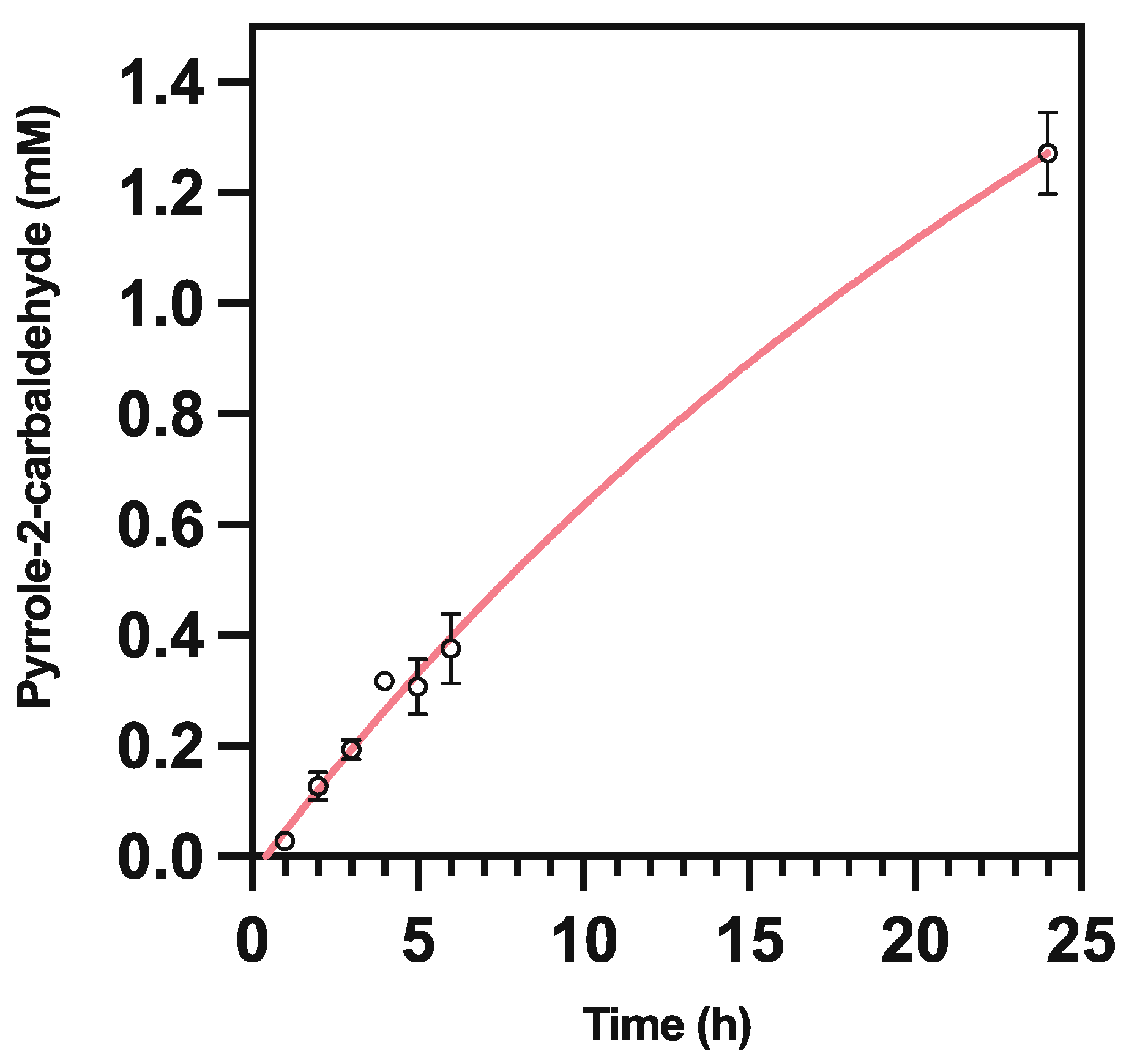

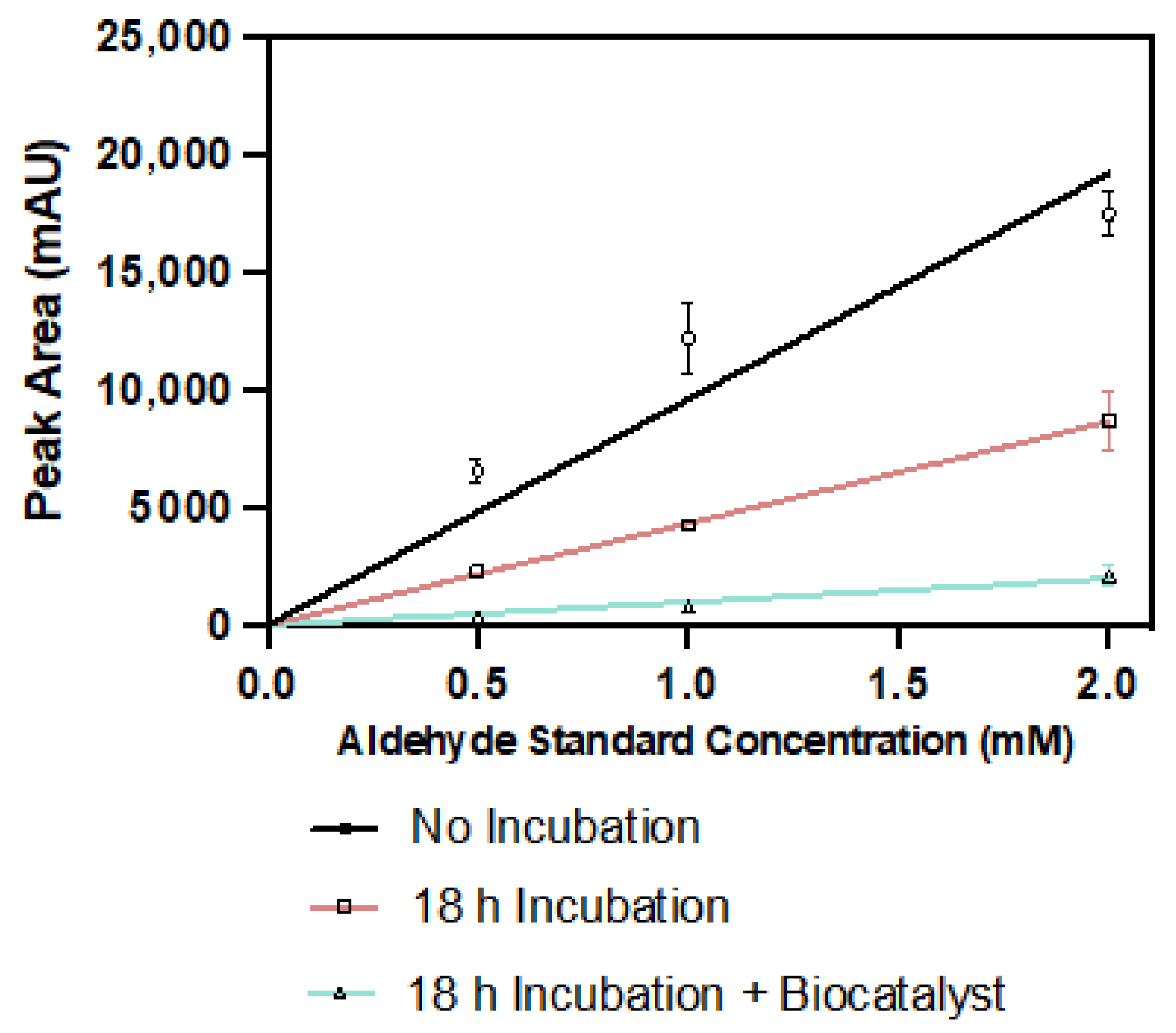

2.4. Pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde Is Unstable

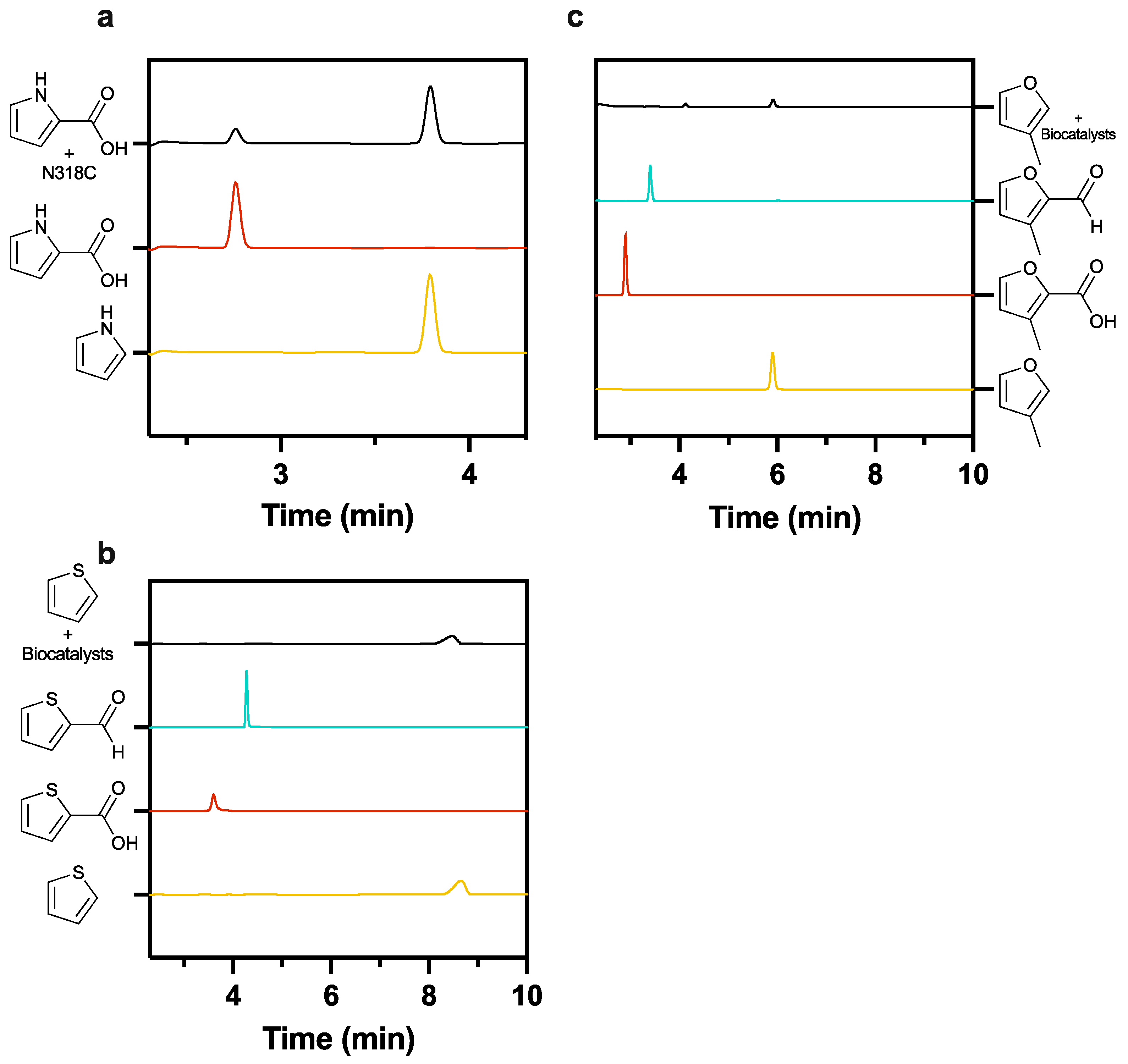

2.5. Neither Furan or Thiophene Class Substrates Yield Product

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Production and Preparation of Active PA0254 Biocatalysts

3.2. Production and Preparation of CARse Biocatalysts

3.2.1. Cloning and Expression

3.2.2. Preparation of Whole-Cell Biocatalyst

3.2.3. Preparation of Purified Biocatalyst

3.3. Carboxylic Acid Reductase Enzyme Screening

3.4. Initial PA0254-CARse Coupling Reactions

3.5. Optimisation of Assay Conditions

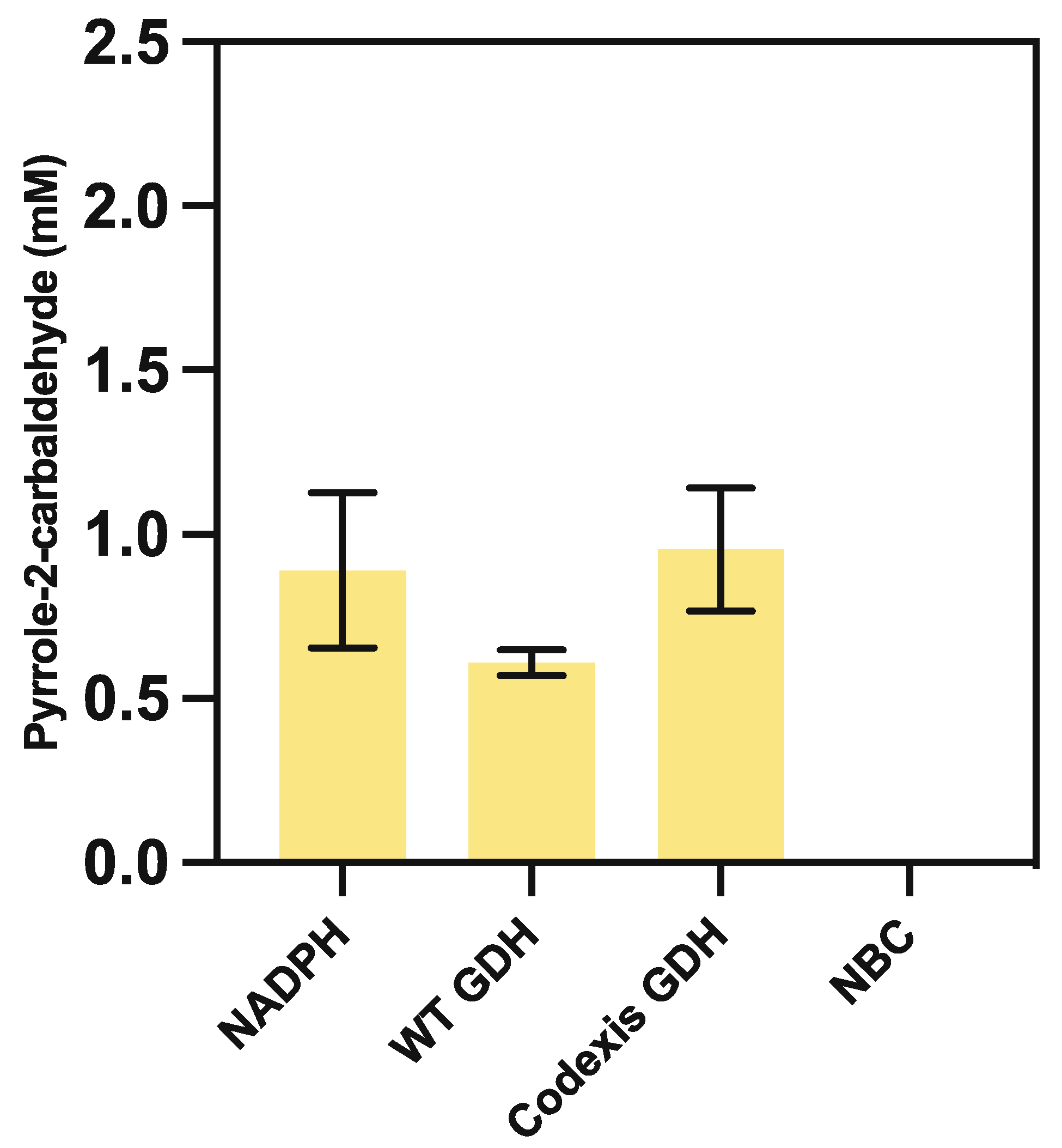

3.5.1. Nicotinamide Recycling

3.5.2. Bicarbonate Optimization

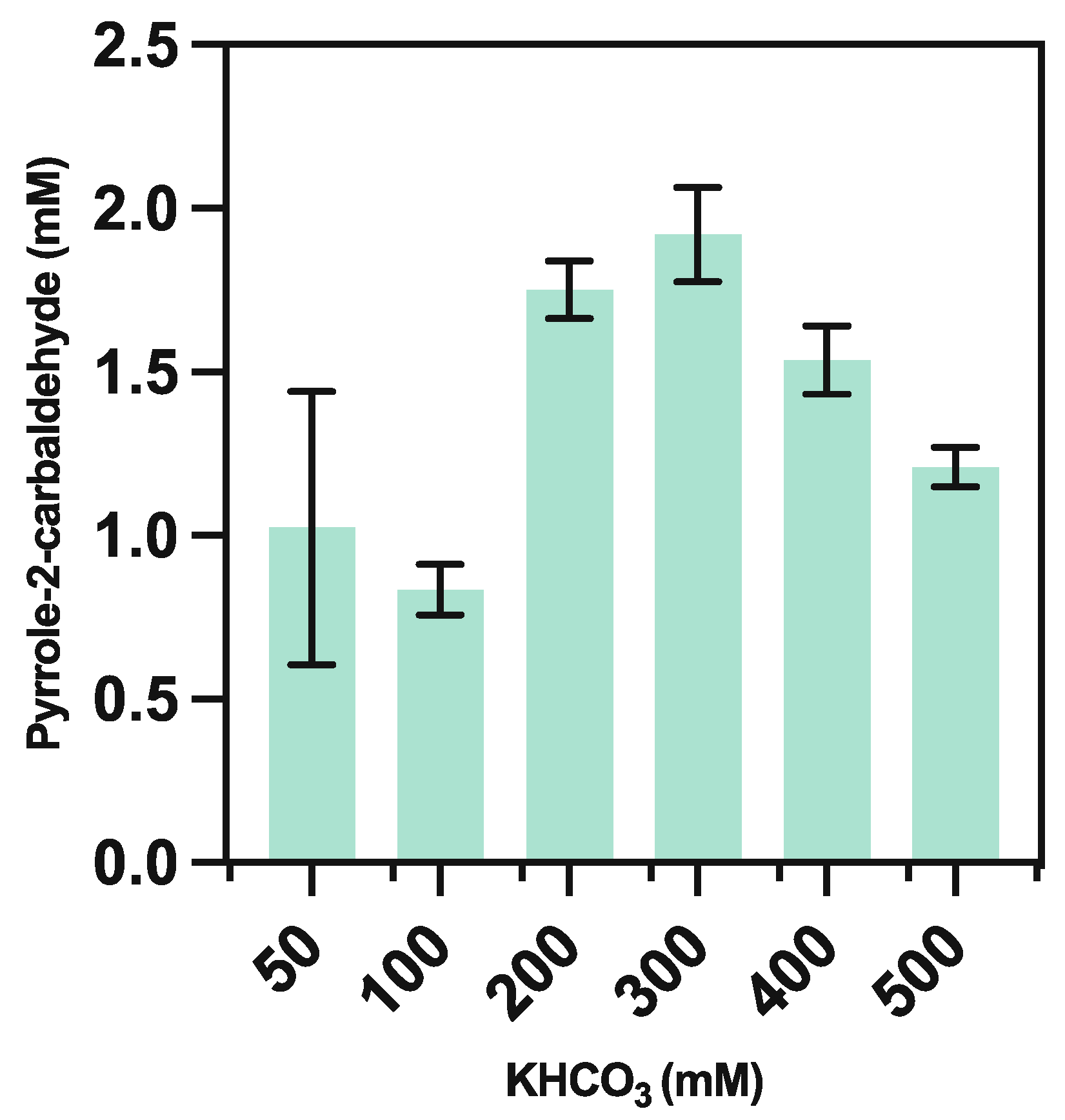

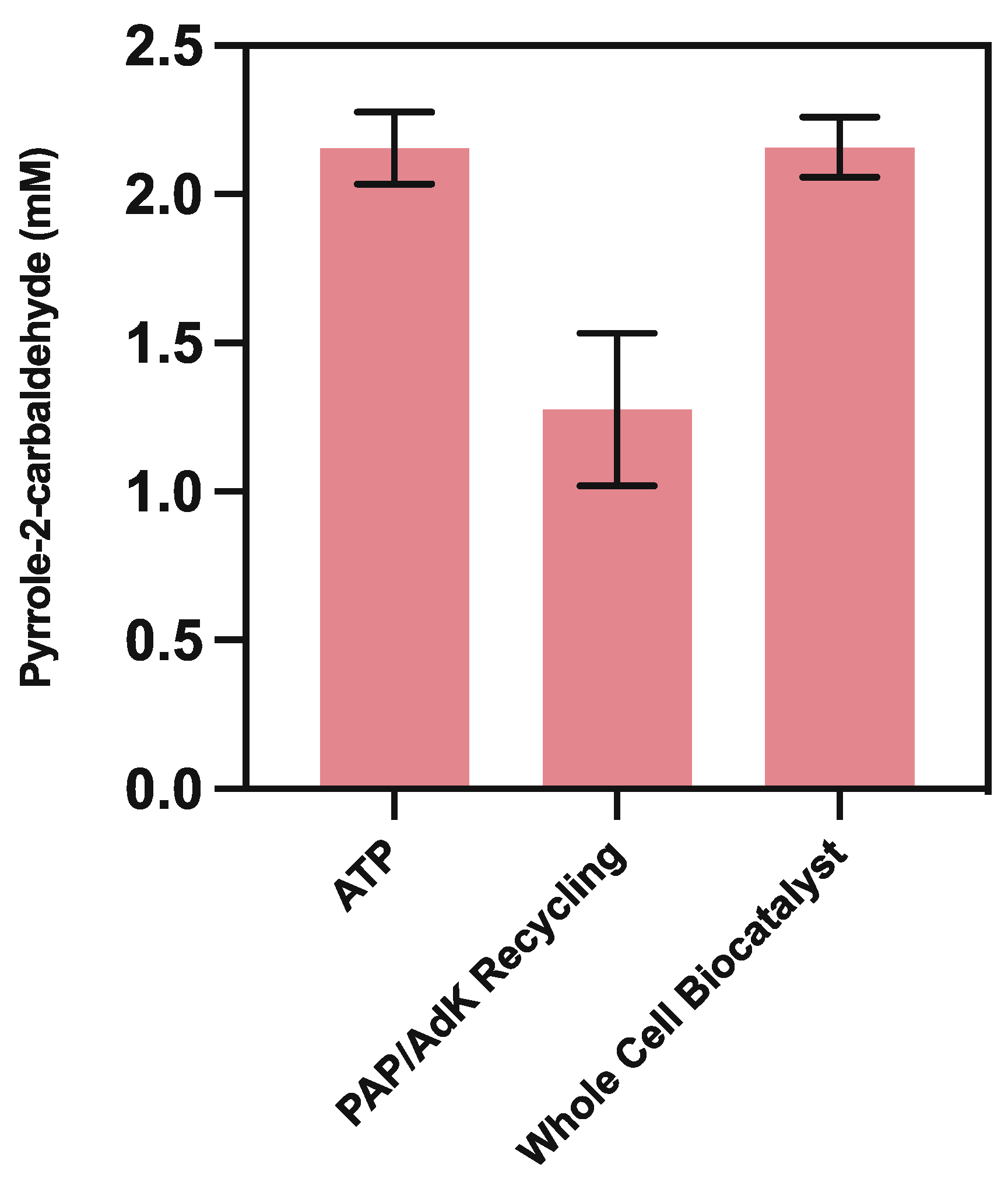

3.5.3. ATP Recycling

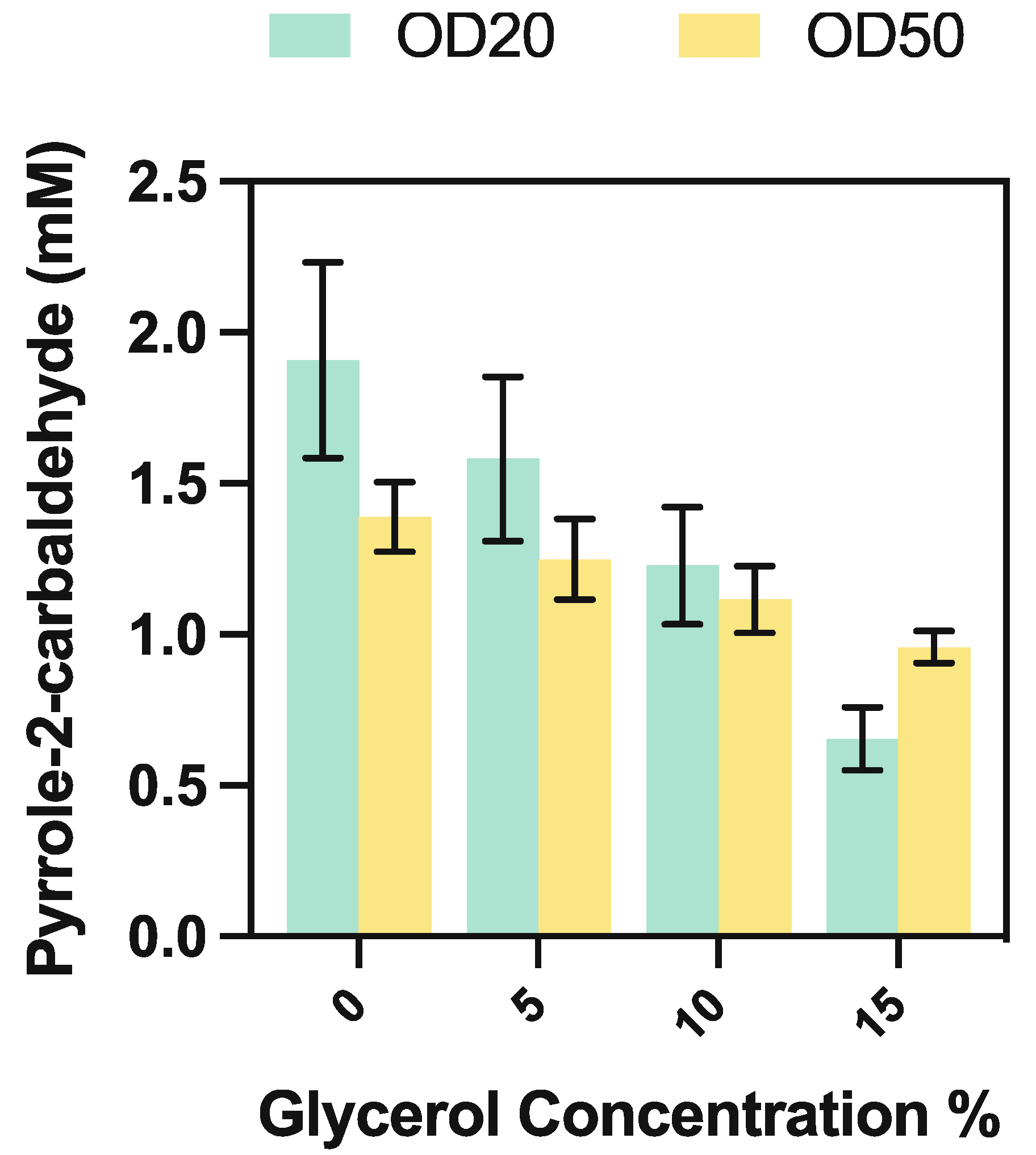

3.5.4. Whole-Cell CARse Biocatalyst Assays

3.5.5. Pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde Degradation Assay

3.6. Analytical Procedures

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hughes, G.; Lewis, J.C. Introduction: Biocatalysis in Industry. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dabral, S.; Schaub, T. The Use of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) as a Building Block in Organic Synthesis from an Industrial Perspective. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aleku, G.A.; Roberts, G.W.; Titchiner, G.R.; Leys, D. Synthetic Enzyme-Catalyzed CO2 Fixation Reactions. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 1781–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, S.A.; Payne, K.A.P.; Leys, D. The UbiX-UbiD system: The biosynthesis and use of prenylated flavin (prFMN). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 632, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aleku, G.A.; Prause, C.; Bradshaw-Allen, R.T.; Plasch, K.; Glueck, S.M.; Bailey, S.S.; Payne, K.A.P.; Parker, D.A.; Faber, K.; Leys, D. Terminal Alkenes from Acrylic Acid Derivatives via Non-Oxidative Enzymatic Decarboxylation by Ferulic Acid Decarboxylases. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 3736–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bloor, S.; Michurin, I.; Titchiner, G.; Leys, D. Prenylated Flavins: Structures and Mechanisms. FEBS J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleku, G.A.; Saaret, A.; Bradshaw-Allen, R.T.; Derrington, S.R.; Titchiner, G.R.; Gostimskaya, I.; Gahloth, D.; Parker, D.A.; Hay, S.; Leys, D. Enzymatic C-H activation of aromatic compounds through CO2 fixation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, K.A.P.; Marshall, S.A.; Fisher, K.; Rigby, S.E.J.; Cliff, M.J.; Spiess, R.; Cannas, D.M.; Larrosa, I.; Hay, S.; Leys, D. Structure and Mechanism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA0254/HudA, a prFMN-Dependent Pyrrole-2-carboxylic Acid Decarboxylase Linked to Virulence. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 2865–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Burgess, K. A new synthesis of symmetric boraindacene (BODIPY) dyes. Chem. Commun. 2008, 40, 4933–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseyin, A.E.; Steele, P.H. An overview of the applications of furfural and its derivatives. Int. J. Adv. Chem. 2015, 3, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.R.; Assadi, Y.; Shemirani, F.; Salavati-Niasari, M. Application of thiophene-2-carbaldehyde-modified mesoporous silica as a new sorbent for separation and preconcentration of palladium prior to inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometric determination. Talanta 2007, 71, 1524–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Yao, P.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, R.; Feng, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, D. Exploring the synthetic applicability of a new carboxylic acid reductase from Segniliparus rotundus DSM 44985. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 115, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Guo, J.; Yang, D.; Sun, Z. Biocatalysis of carboxylic acid reductases: Phylogenesis, catalytic mechanism and potential applications. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnigan, W.; Thomas, A.; Cromar, H.; Gough, B.; Snajdrova, R.; Adams, J.P.; Littlechild, J.A.; Harmer, N.J. Characterization of Carboxylic Acid Reductases as Enzymes in the Toolbox for Synthetic Chemistry. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moura, M.; Pertusi, D.; Lenzini, S.; Bhan, N.; Broadbelt, L.J.; Tyo, K.E. Characterizing and predicting carboxylic acid reductase activity for diversifying bioaldehyde production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahloth, D.; Dunstan, M.S.; Quaglia, D.; Klumbys, E.; Lockhart-Cairns, M.P.; Hill, A.M.; Derrington, S.R.; Scrutton, N.S.; Turner, N.J.; Leys, D. Structures of carboxylic acid reductase reveal domain dynamics underlying catalysis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Resnick, S.M.; Zehnder, A.J. In vitro ATP regeneration from polyphosphate and AMP by polyphosphate:AMP phosphotransferase and adenylate kinase from Acinetobacter johnsonii 210A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 2045–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, S.A.; Payne, K.A.P.; Fisher, K.; Titchiner, G.R.; Levy, C.; Hay, S.; Leys, D. UbiD domain dynamics underpins aromatic decarboxylation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjapur, A.M.; Prather, K.L. Microbial engineering for aldehyde synthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 1892–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horvat, M.; Winkler, M. In Vivo Reduction of Medium- to Long-Chain Fatty Acids by Carboxylic Acid Reductase (CAR) Enzymes: Limitations and Solutions. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 5076–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahloth, D.; Fisher, K.; Payne, K.A.P.; Cliff, M.; Levy, C.; Leys, D. Structural and biochemical characterisation of the prenylated flavin mononucleotide-dependent indole-3-carboxylic acid decarboxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmolzer, K.; Madje, K.; Nidetzky, B.; Kratzer, R. Bioprocess design guided by in situ substrate supply and product removal: Process intensification for synthesis of (S)-1-(2-chlorophenyl)ethanol. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 108, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Concentration of KHCO3 (mM) | Measured pH |

|---|---|

| 50 | 6.49 |

| 100 | 6.74 |

| 200 | 7.01 |

| 300 | 7.16 |

| 400 | 7.35 |

| 500 | 7.44 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Titchiner, G.R.; Marshall, S.A.; Miscikas, H.; Leys, D. Biosynthesis of Pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde via Enzymatic CO2 Fixation. Catalysts 2022, 12, 538. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/catal12050538

Titchiner GR, Marshall SA, Miscikas H, Leys D. Biosynthesis of Pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde via Enzymatic CO2 Fixation. Catalysts. 2022; 12(5):538. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/catal12050538

Chicago/Turabian StyleTitchiner, Gabriel R., Stephen A. Marshall, Herkus Miscikas, and David Leys. 2022. "Biosynthesis of Pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde via Enzymatic CO2 Fixation" Catalysts 12, no. 5: 538. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/catal12050538