Whole Exome Sequencing of Extreme Morbid Obesity Patients: Translational Implications for Obesity and Related Disorders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. DNA Library Preparation, Exome Capture and Sequencing Protocol

2.2. Sequence Read Processing, Alignment, Bioinformatics and Genetic Analyses

3. Clinical Reports

| Test | Value | Normal reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) * | 7.4 mU/L | 0.3–5.0 mU/L |

| Free T4 * | 9.5 pmol/L | 10.3–25.7 pmol/L |

| Antithyroglobulin (ATG) and antithyroperoxidase (ATPO) antibodies * | Both negative | <9.0 IU/mL (ATG)<116 IU/mL (ATPO) |

| Prolactin * | 2908 pmol/L | 82–504 pmol/L |

| Macroprolactin * | Negative (71% recovery) | >50% recovery |

| Total cholesterol $ | 4.84 mmol/L | 4.4 mmol/L |

| HDL cholesterol $ | 0.85 mmol/L | >1.16 mmol/L |

| LDL cholesterol $ | 1.99 mmol/L | <2.84 mmol/L |

| Triglycerides $ | 3.11 mmol/L | <1.02 mmol/L |

| Fasting plasma glucose $ | 5.33 mmol/L | 3.89–5.5 mmol/L |

| Fasting insulin $ | 13 μU/mL | 1.8–4.6 μU/mL |

| Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) & | 71.25 nmol/L | 130–563 nmol/L |

| Growth hormone (GH)/glucose &# | 0.06 μg/L/3.55 mmol/L | >5 μg/L/<1.94 mmol/L |

| Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (morning) | 1.60 pmol/L | 2.2–13.2 pmol/L |

| Cortisol (morning) | 0.68 μmol/L | 0.14–0.70 μmol/L |

| Leptin | 8.1 * and 69.7 μg/L & | Detectable |

| Total testosterone & | 0.90 nmol/L | 3.47–41.60 nmol/L |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) & | Undetectable | 0.5–10.5 IU/L |

| Luteinizing hormone (LH) & | Undetectable | 0.5–7.9 IU/L |

| Total calcium ^ | 2.62 mmol/L | 2.40–2.64 mmol/L |

| Inorganic phosphate ^ | 173.4 mmol/L | 108.4–164.2 mmol/L |

| Magnesium ^ | 1.1 mmol/L | 0.7–0.9 mmol/L |

| Alkaline phosphatise ^ | 114 U/L | 66–571 U/L |

| 25-hydroxy vitamin D ^ | 85 mmol/L | >75 mmol/L |

| Parathyroid hormone (PTH) ^ | 2.6 pmol/L | 1.0–5.5 pmol/L |

| Selenium @ | 0.03 μmol/L | 0.25–2.4 μmol/L |

| Total urinary protein @ | 0.08 g/24 hours | <0.15 g/24 hours |

4. Results

| Patient | Variant | Chr | Position | Ref All | Alt All | Identifier | Classification | Gene | Transcript | Exon | HGVS Coding | HGVS Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11:73689104-SNV | 11 | 73,689,104 | G | A | rs660339 | Nonsyn SNV | UCP2 | NM_003355 | 4 | c.164C>T | p.Ala55Val |

| 2 | 12:8757523-Ins | 12 | 8,757,523 | - | A | rs5796316 | Splicing | AICDA | NM_020661 | 4 | c.428-5_428-4insT | |

| 2 | 19:55873642-SNV | 19 | 55,873,642 | C | T | rs4252574 | Nonsyn SNV | FAM71E2 | NM_001145402 | 3 | c.535G>A | p.Glu179Lys |

| Patient | Single Nucleotide Variant | Chromosome | Position | Identifier | Gene | dbSNP MAF Frequency | Alleles | ReferenceAllele | Reference Aminoacid | Altered Aminoacid | HGVS Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

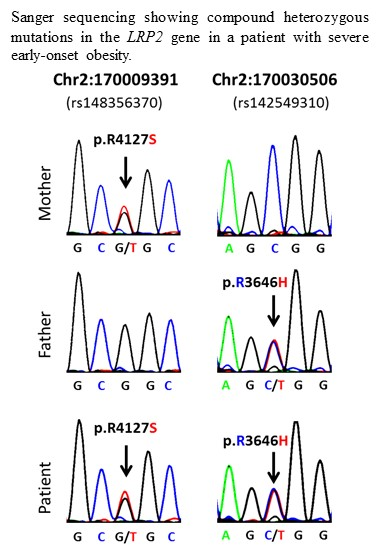

| 1 | 2:170009391-SNV | 2 | 170009391 | rs148356370 | LRP2 | 0.005 | G/T | G | R | S | p.R4127S |

| 1 | 2:170030506-SNV | 2 | 170030506 | rs142549310 | LRP2 | 0.002 | C/T | C | R | H | p.R3646H |

| 1 | 11:10518373-SNV | 11 | 10518373 | rs144107914 | AMPD3 | 0.001 | C/T | C | S | L | p.S323L |

| 1 | 11:10527316-SNV | 11 | 10527316 | N/A | AMPD3 | *** | A/G | G | R | Q | p.R571Q |

| 1 | 11:56468198-SNV | 11 | 56468198 | rs4990194 | OR8U8-OR9G1 | 0.069 | A/G | A | Y | C | p.Y112C |

| 1 | 11:56468212-SNV | 11 | 56468212 | rs591369 | OR8U8-OR9G1 | ** | A/G | G | V | M | p.V117M |

| 1 | 11:56468554-SNV | 11 | 56468554 | rs12420076 | OR8U8-OR9G1 | 0.061 | A/C | A | K | Q | p.K231Q |

| 1 | 11:56468560-SNV | 11 | 56468560 | rs10896516 | OR8U8-OR9G1 | ** | C/T | T | Y | H | p.Y233H |

| 1 | 11:56468561-SNV | 11 | 56468561 | rs10896517 | OR8U8-OR9G1 | 0.047 | A/G | A | Y | C | p.Y233C |

| 1 | 11:62748503-SNV | 11 | 62748503 | rs150409056 | SLC22A6 | * | G/T | G | R | S | p.R331S |

| 1 | 11:62749384-SNV | 11 | 62749384 | rs200609617 | SLC22A6 | *** | C/T | C | A | T | p.A243T |

| 2 | 2:179507021-SNV | 2 | 179507021 | N/A | TTN | *** | G/A | G | R | C | p.R4436C |

| 2 | 2:179577628-SNV | 2 | 179577628 | N/A | TTN | *** | C/T | C | V | I | p.V7798I |

| 2 | 2:179634421-SNV | 2 | 179634421 | rs200875815 | TTN | *** | T/G | T | T | P | c.8749A>C |

| 2 | 3:49716372-SNV | 3 | 49716372 | N/A | APEH | *** | A/G | G | R | H | p.R383H |

| 2 | 3:49720698-SNV | 3 | 49720698 | N/A | APEH | *** | A/G | G | A | T | p.A708T |

| 2 | 16:84203467-SNV | 16 | 84203467 | rs143322223 | DNAAF1 | *** | C/G | C | E | Q | p.E345Q |

| 2 | 16:84208329-SNV | 16 | 84208329 | rs139519641 | DNAAF1 | * | A/G | A | ? | ? | Splicing |

| 2 | 19:55239223-SNV | 19 | 55239223 | rs117372288 | KIR3DL3 | *** | A/G | A | V | I | p.V168I |

| 2 | 19:55241240-SNV | 19 | 55241240 | rs111516669 | KIR3DL3 | ** | A/G | A | V | I | p.V313I |

| Pathways of Candidate Morbid Obesity Genes | Genes from Input List in Pathway | p-Value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP, ITP metabolism | AMPD3 | 1.107e-3 | 6.640e-3 |

| Regulation of lipid metabolism PPAR regulation of lipid metabolism | UCP2 | 1.851e-2 | 3.164e-2 |

| Development of insulin, IGF-1 and TNF-alpha in brown adipocyte differentiation | UCP2 | 2.332e-2 | 3.164e-2 |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases | UCP2 | 2.594e-2 | 3.164e-2 |

| Oxidative stress role of Sirtuin1 and PGC1 alpha in the activation of the defence system | UCP2 | 2.637e-2 | 3.164e-2 |

| CTP UTP metabolism | AICDA | 4.709e-2 | 4.709e-2 |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- Malik, V.S.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Global obesity: Trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maes, H.H.; Neale, M.C.; Eaves, L.J. Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav. Genet. 1997, 27, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed Moustafa, J.S.; Froguel, P. From obesity genetics to the future of personalized obesity therapy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 402–413. [Google Scholar]

- Loos, R.J. Genetic determinants of common obesity and their value in prediction. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 26, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, S.; O’Rahilly, S. Genetics of obesity in humans. Endocr. Rev. 2006, 27, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai, M.; Ramachandrappa, S.; Joachim, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, R.; Nuthalapati, N.; Ramanathan, V.; Strochlic, D.E.; Ferket, P.; Linhart, K.; et al. Loss of function of the melanocortin 2 receptor accessory protein 2 is associated with mammalian obesity. Science 2013, 341, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bamshad, M.J.; Ng, S.B.; Bigham, A.W.; Tabor, H.K.; Emond, M.J.; Nickerson, D.A.; Shendure, J. Exome sequencing as a tool for mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, W.K.; Ben-Omran, T.; Darras, B.T.; Prabhu, S.P.; de Vivo, D.C.; Vatta, M.; Yang, Y.; Eng, C.M.; Chung, W.K. Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing: A novel autosomal recessive spastic ataxia. JAMA Neurol. 2013, 70, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Need, A.C.; Shashi, V.; Hitomi, Y.; Schoch, K.; Shianna, K.V.; McDonald, M.T.; Meisler, M.H.; Goldstein, D.B. Clinical application of exome sequencing in undiagnosed genetic conditions. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veltman, J.A.; Brunner, H.G. De novo mutations in human genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Muzny, D.M.; Reid, J.G.; Bainbridge, M.N.; Willis, A.; Ward, P.A.; Braxton, A.; Beuten, J.; Xia, F.; Niu, Z.; et al. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1502–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, R.; Him Cheung, Y.; Shen, Y.; Lanzano, P.; Mirza, N.M.; Ten, S.; Maclaren, N.K.; Motaghedi, R.; Han, J.C.; Yanovski, J.A.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel lepr mutations in individuals with severe early onset obesity. Obesity 2013, 22, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, A.E. Whole Exome Sequencing Case-Control Using 1000 Severe Obesity Cases Identifies Putative New Loci and Replicates Previously Established Loci; American Society of Human Genetics: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scheidecker, S.; Etard, C.; Pierce, N.W.; Geoffroy, V.; Schaefer, E.; Muller, J.; Chennen, K.; Flori, E.; Pelletier, V.; Poch, O.; et al. Exome sequencing of bardet-biedl syndrome patient identifies a null mutation in the bbsome subunit bbip1 (bbs18). J. Med. Genet. 2014, 51, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, S.Y.; Youn, B.S.; Byun, K.; Huang, H.; Namkoong, C.; Jang, P.G.; Lee, J.Y.; Jo, Y.H.; Kang, G.M.; Kim, H.K.; et al. Clusterin and lrp2 are critical components of the hypothalamic feeding regulatory pathway. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleury, C.; Neverova, M.; Collins, S.; Raimbault, S.; Champigny, O.; Levi-Meyrueis, C.; Bouillaud, F.; Seldin, M.F.; Surwit, R.S.; Ricquier, D.; et al. Uncoupling protein-2: A novel gene linked to obesity and hyperinsulinemia. Nat. Genet. 1997, 15, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbari, N.F.; Pasek, R.C.; Malarkey, E.B.; Yazdi, S.M.; McNair, A.D.; Lewis, W.R.; Nagy, T.R.; Kesterson, R.A.; Yoder, B.K. Leptin resistance is a secondary consequence of the obesity in ciliopathy mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7796–7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, C.A.; Heon, E.; Zhen, M. Ciliary dysfunction and obesity. Clin. Genet. 2010, 77, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hama, H.; Saito, A.; Takeda, T.; Tanuma, A.; Xie, Y.; Sato, K.; Kazama, J.J.; Gejyo, F. Evidence indicating that renal tubular metabolism of leptin is mediated by megalin but not by the leptin receptors. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 3935–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, M.O.; Spuch, C.; Antequera, D.; Rodal, I.; de Yebenes, J.G.; Molina, J.A.; Bermejo, F.; Carro, E. Megalin mediates the transport of leptin across the blood-csf barrier. Neurobiol. Aging 2008, 29, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronow, B.J.; Lund, S.D.; Brown, T.L.; Harmony, J.A.; Witte, D.P. Apolipoprotein j expression at fluid-tissue interfaces: Potential role in barrier cytoprotection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pober, B.R.; Longoni, M.; Noonan, K.M. A review of donnai-barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal (db/foar) syndrome: Clinical features and differential diagnosis. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2009, 85, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu-Ugalde, J.; Theilig, F.; Behrends, T.; Drebes, J.; Sieland, C.; Subbarayal, P.; Kohrle, J.; Hammes, A.; Schomburg, L.; Schweizer, U. Mutation of megalin leads to urinary loss of selenoprotein p and selenium deficiency in serum, liver, kidneys and brain. Biochem. J. 2010, 431, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- May, P.; Woldt, E.; Matz, R.L.; Boucher, P. The ldl receptor-related protein (lrp) family: An old family of proteins with new physiological functions. Ann. Med. 2007, 39, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willnow, T.E.; Hilpert, J.; Armstrong, S.A.; Rohlmann, A.; Hammer, R.E.; Burns, D.K.; Herz, J. Defective forebrain development in mice lacking gp330/megalin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 8460–8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.; Stottmann, R.W.; Furley, A.J.; Beier, D.R. A forward genetic screen in mice identifies mutants with abnormal cortical patterning. Cereb. Cortex 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, S.; Al-Gazali, L.; Hill, R.S.; Donnai, D.; Black, G.C.; Bieth, E.; Chassaing, N.; Lacombe, D.; Devriendt, K.; Teebi, A.; et al. Mutations in lrp2,which encodes the multiligand receptor megalin, cause donnai-barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal syndromes. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 957–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.H.; Lee, W.J.; Wang, W.; Huang, M.T.; Lee, Y.C.; Pan, W.H. Ala55val polymorphism on ucp2 gene predicts greater weight loss in morbidly obese patients undergoing gastric banding. Obes. Surg. 2007, 17, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktavianthi, S.; Trimarsanto, H.; Febinia, C.A.; Suastika, K.; Saraswati, M.R.; Dwipayana, P.; Arindrarto, W.; Sudoyo, H.; Malik, S.G. Uncoupling protein 2 gene polymorphisms are associated with obesity. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2012, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buemann, B.; Schierning, B.; Toubro, S.; Bibby, B.M.; Sorensen, T.; Dalgaard, L.; Pedersen, O.; Astrup, A. The association between the val/ala-55 polymorphism of the uncoupling protein 2 gene and exercise efficiency. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2001, 25, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, M.R.; Daniels, L.A.; Davis, S.D.; Zariwala, M.A.; Leigh, M.W. Primary ciliary dyskinesia. Recent advances in diagnostics, genetics, and characterization of clinical disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 913–922. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C.G.; Meyre, D.; Samson, C.; Boyle, C.; Lecoeur, C.; Tauber, M.; Jouret, B.; Jaquet, D.; Levy-Marchal, C.; Charles, M.A.; et al. Association of melanin-concentrating hormone receptor 1 5' polymorphism with early-onset extreme obesity. Diabetes 2005, 54, 3049–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cota, D.; Proulx, K.; Smith, K.A.; Kozma, S.C.; Thomas, G.; Woods, S.C.; Seeley, R.J. Hypothalamic mtor signaling regulates food intake. Science 2006, 312, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, J.R.; Watts, A.J.; Roper, V.C.; Croyle, M.J.; van Groen, T.; Wyss, J.M.; Nagy, T.R.; Kesterson, R.A.; Yoder, B.K. Disruption of intraflagellar transport in adult mice leads to obesity and slow-onset cystic kidney disease. Curr. Biol. CB 2007, 17, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, V.; Stoetzel, C.; Schlicht, D.; Messaddeq, N.; Koch, M.; Flori, E.; Danse, J.M.; Mandel, J.L.; Dollfus, H. Transient ciliogenesis involving bardet-biedl syndrome proteins is a fundamental characteristic of adipogenic differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1820–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen Gupta, P.; Prodromou, N.V.; Chapple, J.P. Can faulty antennae increase adiposity? The link between cilia proteins and obesity. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 203, 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, N.E.; Zhao, T.; Cankaya, M.; Theil, T.; Zhou, X.; Alvarez-Bolado, G. Role of neuroepithelial sonic hedgehog in hypothalamic patterning. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 6989–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British 1958 birth cohort DNA Collection. Available online: http://www.b58cgene.sgul.ac.uk/ (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Bloss, C.S.; Duvvuri, V.; Kaye, W.; Schork, N.J.; Berrettini, W.; Hakonarson, H.; Price Foundation Collaborative Group. A genome-wide association study on common snps and rare cnvs in anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 949–959. [Google Scholar]

- Brondani, L.A.; Assmann, T.S.; de Souza, B.M.; Boucas, A.P.; Canani, L.H.; Crispim, D. Meta-analysis reveals the association of common variants in the uncoupling protein (ucp) 1–3 genes with body mass index variability. PLoS One 2014, 9, e96411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.J.; Zhu, H.; He, H.; Wu, K.H.; Li, J.; Chen, X.D.; Zhang, J.G.; Shen, H.; Tian, Q.; Krousel-Wood, M.; et al. Replication of 6 obesity genes in a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies from diverse ancestries. PLoS One 2014, 9, e96149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur, D.G.; Manolio, T.A.; Dimmock, D.P.; Rehm, H.L.; Shendure, J.; Abecasis, G.R.; Adams, D.R.; Altman, R.B.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Ashley, E.A.; et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature 2014, 508, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, C.L.; Majewski, J.; Schwartzentruber, J.; Samuels, M.E.; Fernandez, B.A.; Bernier, F.P.; Brudno, M.; Knoppers, B.; Marcadier, J.; Dyment, D.; et al. Forge canada consortium: Outcomes of a 2-year national rare-disease gene-discovery project. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 94, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, B.; Tekin, M.; Mahdieh, N. The promise of whole-exome sequencing in medical genetics. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 59, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Paz-Filho, G.; Boguszewski, M.C.S.; Mastronardi, C.A.; Patel, H.R.; Johar, A.S.; Chuah, A.; Huttley, G.A.; Boguszewski, C.L.; Wong, M.-L.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; et al. Whole Exome Sequencing of Extreme Morbid Obesity Patients: Translational Implications for Obesity and Related Disorders. Genes 2014, 5, 709-725. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/genes5030709

Paz-Filho G, Boguszewski MCS, Mastronardi CA, Patel HR, Johar AS, Chuah A, Huttley GA, Boguszewski CL, Wong M-L, Arcos-Burgos M, et al. Whole Exome Sequencing of Extreme Morbid Obesity Patients: Translational Implications for Obesity and Related Disorders. Genes. 2014; 5(3):709-725. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/genes5030709

Chicago/Turabian StylePaz-Filho, Gilberto, Margaret C.S. Boguszewski, Claudio A. Mastronardi, Hardip R. Patel, Angad S. Johar, Aaron Chuah, Gavin A. Huttley, Cesar L. Boguszewski, Ma-Li Wong, Mauricio Arcos-Burgos, and et al. 2014. "Whole Exome Sequencing of Extreme Morbid Obesity Patients: Translational Implications for Obesity and Related Disorders" Genes 5, no. 3: 709-725. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/genes5030709