Tourism Imaginary and Landscape at Heritage Site: A Case in Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China

Abstract

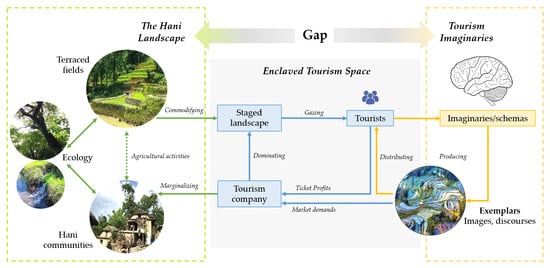

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theories of the Social Imaginary and Tourism Imaginary

“Prospective tourists are invited to imagine themselves in a paradisiacal environment, a vanished Eden, where the local landscape and population are to be consumed through observation, embodied sensation, and imagination.”[26]

“Tourists are not merely searching for authenticity of the Other. They also search for authenticity of, and between, themselves. The toured objects or tourism can be just a means or medium by which tourist are called together, and then, an authentic interpersonal relationship between themselves is experience subsequently.”[43] (p. 364)

2.2. The Hani Landscape

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Tourism Imaginaries in Tourist Discourses and Images

4.1.1. Discourse Analysis

“Climbing to the top of the terraced fields to see the erratic sea of clouds, the looming half-mountain villages, the majestic terraces, the scenery will change with the ethereal light and fog, forming a beautiful landscape and countryside scenery. It is a paradise of light and shadow for photography lovers. But what you see now is 1300 years of the Hani!”(Tourist comment, 2019)

“Most of the beautiful pictures of Hani terraces we saw were from the same perspective: looking down. It is an ink painting drawn by a large number of curves that are never repeated on the edge of the terraces, and it is better to be supplemented with colorful rays of the sky. This turns the terraces into a simple flat object. But you can only realize the greatness of Hani people when standing on the side of terraces, seeing the level and height of terraced fields with the naked eye.”(Tourist comment, 2019)

“During the Chinese New Year, rice fields are filled with water. It is the best moment of light and shadow. In the early morning or at dusk, there are different visual effects under different refraction. This is a paradise for photography.”(Tourist comment, 2019)

“Among them, Bada and Tiger’s Mouth are the best places to watch the sunset, and Duoyishu is the best place to watch the sunrise. The best time to shoot Yuanyang terraced fields is from November to April of the following year, because the terraced fields will be filled with water after the autumn harvest until the seedlings are planted in the following year. At this time, the terraced fields have a strong sense of hierarchy, sparkling under the sunlight. Many of the photos of terraced fields we saw on the Internet were taken during this time.”(Tourist comment, 2019)

4.1.2. Image Analysis

4.2. Tourism Development and the Shaping of Landscape Imaginaries

4.2.1. Production of Tourism Imaginaries about the Hani Landscape

4.2.2. Power Relations, Community Resistance, and New Landscape Representations

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terkenli, T.S. Towards a theory of the landscape: The Aegean landscape as a cultural image. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 57, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.S. Landscapes of tourism: Towards a global cultural economy of space? Tour. Geogr. 2002, 4, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.S. Tourism and landscape. In A Companion to Tourism; Lew, A.A., Hall, C.M., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.; Ollenburg, C.; Zhong, L. Cultural landscape in Mongolian tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daugstad, K. Negotiating landscape in rural tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 402–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslinga, J.; Groote, P.; Vanclay, F. Understanding the historical institutional context by using content analysis of local policy and planning documents: Assessing the interactions between tourism and landscape on the Island of Terschelling in the Wadden Sea Region. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heslinga, J.; Groote, P.; Vanclay, F. Towards resilient regions: Policy recommendations for stimulating synergy between tourism and landscape. Land 2020, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brush, R.; Chenoweth, R.E.; Barman, T. Group differences in the enjoyability of driving through rural landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 47, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerhall, C.M. Clustering predictors of landscape preference in the traditional Swedish cultural landscape: Prospect-refuge, mystery, age and management. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.G. Ascertaining landscape perceptions and preferences with pair-wise photographs: Planning rural tourism in Extremadura, Spain. Landsc. Res. 2002, 27, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. Consuming Places; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison, C.; MacLeod, N.E.; Shaw, S.J. Leisure and Tourism Landscapes: Social and Cultural Geographies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T. Post-Conflict Heritage, Postcolonial Tourism: Tourism, Politics and Development at Angkor; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C. Tourism and the symbols of identity. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N.J. Privileging the male gaze: Gendered tourism landscapes. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 884–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.; Lyall, J. The Accelerated Sublime: Landscape, Tourism, and Identity; Greenwood Publishing Group: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Godis, N.; Nilsson, J.H. Memory tourism in a contested landscape: Exploring identity discourses in Lviv, Ukraine. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1690–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringer, G. (Ed.) Destinations: Cultural Landscapes of Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Jewell, B.; McKinnon, S. Movie tourism—A new form of cultural landscape? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Graburn, N. Tourism and cultural landscapes in Southern China’s highlands. Via. Tour. Rev. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castoriadis, C. The Imaginary Institution of Society; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, J. The function and field of speech and language in psychoanalysis. In Écrits: A Selection; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 30–113. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism; Verso: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. Modern social imaginaries. Public Cult. 2002, 14, 91–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. Tourism and the geographical imagination. Leis. Stud. 1992, 11, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.B. Tourism imaginaries: A conceptual approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.B.; Graburn, N.H. Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ce, Q.; Tian, M. Tourism situation: Between imaginary and place. J. Beijing Int. Stud. Univ. 2015, 37, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Gravari-Barbas, M.; Graburn, N. Tourism Imaginaries at the Disciplinary Crossroads: Place, Practice, Media; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gravari-Barbas, M.; Graburn, N. Tourist imaginaries. Via. Tour. Rev. 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.R. Tourism and Geopolitics: Issues and Concepts from Central and Eastern Europe; CABI: Egham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, K. Tourism and the geopolitics of Buddhist heritage in Nepal. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogués-Pedregal, A.M. Anthropological contributions to tourism studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafanezhad, M.; Norum, R. The anthropocenic imaginary: Political ecologies of tourism in a geological epoch. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruner, E.M. Culture on Tour: Ethnographies of Travel; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Conventio; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ivy, M. Discourses of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, C. The imaginary. Anthropol. Theory 2006, 6, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, C. Life Stories: The Creation of Coherence; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Statistical Division. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008; (No. 83); United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Condition of Postmodernity; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1990; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch, E. In principles of categorization. In Cognition and Categorization; Rosch, E., Lloyd, B., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1978; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Du Gay, P.; du Du Gay, P. (Eds.) Production of Culture/Cultures of Production; Sage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, J. Hani rice terraces of Honghe—The harmonious landscape of nature and humans. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 655–667. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, H.; Zhou, S. Human-environment system boundaries: A case study of the Honghe hani rice terraces as a world heritage cultural landscape. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10733–10755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Lun, F.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Min, Q. An analysis on crops choice and its driving factors in agricultural heritage systems—A case of Honghe hani rice terraces system. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNESCO Nomination form of Cultural Landscape of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces. 2013. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1111.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Shi, J. Honghe Declaration Global Declaration on Protection and Development of Terraces. 2010. Available online: http://www.paesaggiterrazzati.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Honghe-Declaration_English_2010l.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Lu, W.; Stepchenkova, S. User-generated content as a research mode in tourism and hospitality applications: Topics, methods, and software. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.; Sellitto, C.; Cox, C.; Buultjens, J. User-generated content (UGC) in tourism: Benefits and concerns of online consumers. In Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Information Systems, Verona, Italy, 8–10 June 2009; pp. 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Marchiori, E.; Cantoni, L. The role of prior experience in the perception of a tourism destination in user-generated content. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B. Exploring place perception a photo-based analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F. The Chinese View of Nature: Tourism in China’s Scenic and Historic Interest Areas. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grimwood, B.S.; Yudina, O.; Muldoon, M.; Qiu, J. Responsibility in tourism: A discursive analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Production and consumption of European cultural tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.B. The glocalisation of heritage through tourism. In Heritage and Globalisation; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010; pp. 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H.; Nicholson-Smith, D. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991; Volume 142, pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Ryan, C.; Zhang, L. Social conflict in communities impacted by tourism. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparon, M.; Stoeckl, N.; Farr, M.; Larson, S. The significance of environmental values for destination competitiveness and sustainable tourism strategy making: Insights from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calgaro, E.; Lloyd, K.; Dominey-Howes, D. From vulnerability to transformation: A framework for assessing the vulnerability and resilience of tourism destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes/Words | Frequency of Mention | Percentage | Themes/Words | Frequency of Mention | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TERRACED FIELDS | 254 | 100% | Life | 9 | 6.25% |

| Pattern | 224 | 88.19% | History | 4 | 2.78% |

| Terraces | 178 | 70.08% | Yi people | 3 | 2.08% |

| Layers | 13 | 5.12% | Custom | 2 | 1.39% |

| Rice fields | 13 | 5.12% | Folklore | 2 | 1.39% |

| Curves | 5 | 1.97% | Language | 2 | 1.39% |

| Continuous | 4 | 1.57% | Local customs | 2 | 1.39% |

| Shape | 4 | 1.57% | CLIMATE/ATMOSPHERIC CHARACTERISTICS | 89 | 100.00% |

| Steep | 4 | 1.57% | Sun/sunshine/light and shadow | 48 | 53.93% |

| Color | 3 | 1.18% | Cloud/mist | 21 | 23.60% |

| Soil/landform | 18 | 7.09% | Weather | 10 | 11.24% |

| Rice | 12 | 4.72% | Sky | 7 | 7.87% |

| PANORAMIC LANDSCAPE | 240 | 100% | Wind | 2 | 2.25% |

| Aesthetics | 118 | 49.17% | BUILDING ENVIRONMENT | 50 | 100.00% |

| Scenery | 31 | 12.92% | Trails and roads | 27 | 54.00% |

| Colorful | 19 | 7.92% | Village | 13 | 26.00% |

| Masterpiece | 18 | 7.50% | Vehicle | 3 | 6.00% |

| Beautiful | 14 | 5.83% | TOURISM | 39 | 100.00% |

| Dynamic | 13 | 5.42% | Tourists | 9 | 23.08% |

| Chinese ink painting | 8 | 3.33% | Food | 8 | 20.51% |

| Boundless | 5 | 2.08% | Accessibility | 6 | 15.38% |

| Misty | 2 | 0.83% | Accommodation | 4 | 10.26% |

| Strange | 2 | 0.83% | Seasonality | 3 | 7.69% |

| Vibrant | 2 | 0.83% | Service | 3 | 7.69% |

| Vivid | 2 | 0.83% | Tourism | 3 | 7.69% |

| Spatial features | 40 | 16.67% | Tour guide | 2 | 5.13% |

| Grand/vast view | 22 | 9.17% | HIGHLAND TERRAIN | 36 | 100.00% |

| Shock | 8 | 3.33% | Mountainous terrain | 18 | 50.00% |

| Remote | 6 | 2.50% | Mountain locations | 9 | 25.00% |

| Deep | 3 | 1.25% | Altitude | 4 | 11.11% |

| Authenticity | 31 | 12.92% | Natural hazard | 3 | 8.33% |

| Unique | 18 | 7.50% | Valley | 2 | 5.56% |

| Genuine | 5 | 2.08% | HERITAGE | 33 | 100.00% |

| Local | 4 | 1.67% | Heritage | 15 | 45.45% |

| Original | 3 | 1.25% | Culture | 8 | 24.24% |

| Illusion | 19 | 7.92% | Core zone | 3 | 9.09% |

| Hidden paradise/wonderland | 10 | 4.17% | Maintenance/sustain | 3 | 9.09% |

| Illusion | 4 | 1.67% | Bells | 2 | 6.06% |

| Magical | 2 | 0.83% | Historical stories | 2 | 6.06% |

| Simple | 2 | 0.83% | TEMPORAL CHANGES | 30 | 100.00% |

| Famous | 10 | 4.17% | Season/time of day | 30 | 100.00% |

| History | 7 | 2.92% | WATERS | 24 | 100.00% |

| History | 3 | 1.25% | Water reflection | 16 | 66.67% |

| Old | 3 | 1.25% | Pool | 2 | 8.33% |

| Hygiene | 7 | 2.92% | Spring | 2 | 8.33% |

| Dirty and messy/poverty | 4 | 1.67% | Water resource | 2 | 8.33% |

| Dirty/poverty | 2 | 0.83% | PHOTOGRAPHY | 18 | 100.00% |

| Countryside | 7 | 2.92% | Photography | 7 | 38.89% |

| Feeling | 5 | 2.08% | Photos | 6 | 33.33% |

| Mood | 2 | 0.83% | Photographer | 3 | 16.67% |

| Safe | 2 | 0.83% | Media | 2 | 11.11% |

| Tranquil | 5 | 2.08% | ECOLOGY | 13 | 100.00% |

| LOCAL PEOPLE | 144 | 100.00% | Animals | 2 | 15.38% |

| Hani people | 61 | 42.36% | Forest | 2 | 15.38% |

| Agricultural activities | 37 | 25.69% | Nature | 6 | 46.15% |

| Generations | 16 | 11.11% |

| Image Composition | Duoyishu | Bada | Tiger’s Mouth | Aicun | Grand Total | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F 2 | P 3 | F | P | F | P | F | P | |||

| LAYER PATTERN | 31 | 36.90% | 9 | 17.31% | 19 | 45.24% | 4 | 23.53% | 63 | 32.31% |

| Overlook of TF 1 + Layer/curve pattern | 31 | 36.90% | 9 | 17.31% | 19 | 45.24% | 4 | 23.53% | 63 | 32.31% |

| VIEWING DECK PANORAMA | 9 | 10.71% | 31 | 59.62% | 5 | 11.90% | 45 | 23.08% | ||

| Overlook of TF + Mountain + Villages + Sky | 9 | 10.71% | 27 | 51.92% | 1 | 2.38% | 37 | 18.97% | ||

| Overlook of TF + Mountain | 4 | 7.69% | 4 | 9.52% | 8 | 4.10% | ||||

| SUNRISE | 28 | 33.33% | 1 | 1.92% | 29 | 14.87% | ||||

| Overlook of TF + Sunrise + Mountain + Sky | 12 | 14.29% | 1 | 1.92% | 13 | 6.67% | ||||

| Overlook of TF + Reflection of sunshine | 10 | 11.90% | 10 | 5.13% | ||||||

| Overlook of TF + Sunshine refraction + Fog | 7 | 8.33% | 7 | 3.59% | ||||||

| TERRACED FIELDS AMID FOG/SEA OF CLOUDS | 14 | 16.67% | 2 | 3.85% | 2 | 4.76% | 4 | 23.53% | 22 | 11.28% |

| Overlook of TF + Fog | 12 | 14.29% | 2 | 3.85% | 2 | 4.76% | 4 | 23.53% | 20 | 10.26% |

| Overlook of TF + Sea of clouds + Sky | 3 | 3.57% | 3 | 1.54% | ||||||

| SUNSET | 4 | 7.69% | 16 | 38.10% | 20 | 10.26% | ||||

| Overlook of TF + Sunset + Mountain + Sky | 4 | 7.69% | 8 | 19.05% | 12 | 6.15% | ||||

| Overlook of TF + Reflection of sunshine | 8 | 19.05% | 8 | 4.10% | ||||||

| BLUE TERRACES | 9 | 52.94% | 9 | 4.62% | ||||||

| Overview of TF + Blue water surface + mountain + sky | 9 | 52.94% | 9 | 4.62% | ||||||

| CLOSE-UP VIEW OF RICE FIELDS | 7 | 13.46% | 7 | 3.59% | ||||||

| Close-up view of TF | 7 | 13.46% | 7 | 3.59% | ||||||

| Grand Total | 84 | 100.00% | 52 | 100.00% | 42 | 100.00% | 17 | 100.00% | 195 | 100.00% |

| Percentage | 43.08% | 26.67% | 21.54% | 8.72% | 100.00% | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Marafa, L. Tourism Imaginary and Landscape at Heritage Site: A Case in Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China. Land 2021, 10, 439. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/land10040439

Wang Z, Marafa L. Tourism Imaginary and Landscape at Heritage Site: A Case in Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China. Land. 2021; 10(4):439. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/land10040439

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhe, and Lawal Marafa. 2021. "Tourism Imaginary and Landscape at Heritage Site: A Case in Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China" Land 10, no. 4: 439. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/land10040439