Rural-Urban Migration and its Effect on Land Transfer in Rural China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data and Method

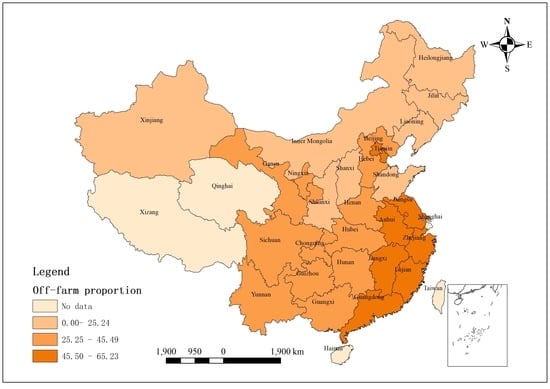

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Definition and Data Description of the Model Variable

(1) Dependent variables

(2) Independent variables

2.2.2. Econometric Model

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics Analysis Result

3.2. Econometric Model Results

3.2.1. The Results of the Econometric Models for Land Transfer Direction of Farmers

3.2.2. The Results of the Econometric Models for Land Transfer Scale of Farmers

3.3. Robustness Check

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Off-farm employment would significantly affect the direction and the scale of land transfer of farmers, and the results are robust. With every 10% increase in off-farm employment, the probability of rent-in land of farmers decreases, on average, by 1.55%, and the average transfer in land area of farmers decreases by 1.04%; With every 10% increase in off-farm employment, the probability of rent-out land of farmers increases, on average, by 4.77%, and the average transfer out land area of farmers increases by 3.98%.

- (2)

- Part-time employment also has a significant impact on the direction and the scale of land transfer of farmers. However, the correlation between part-time employment and land transfer in is not robust. Specifically, with every 10% increase in part-farm employment, the probability of rent-out land of farmers increases, on average, by 7.64%, and the average transfer out land area of farmers increases by 6.85%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prishchepov, A.V.; Müller, D.; Dubinin, M.; Baumann, M.; Radeloff, V.C. Determinants of agricultural land abandonment in post-Soviet European Russia. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumm, K.-I.; Hessle, A. Economic Comparison between Pasture-Based Beef Production and Afforestation of Abandoned Land in Swedish Forest Districts. Land 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colantoni, A.; Egidi, G.; Quaranta, G.; D’Alessandro, R.; Vinci, S.; Turco, R.; Salvati, L. Sustainable Land Management, Wildfire Risk and the Role of Grazing in Mediterranean Urban-Rural Interfaces: A Regional Approach from Greece. Land 2020, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- KC, B.; Race, D. Outmigration and Land-Use Change: A Case Study from the Middle Hills of Nepal. Land 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ojha, H.R.; Shrestha, K.K.; Subedi, Y.R.; Shah, R.; Nuberg, I.; Heyojoo, B.; Cedamon, E.D.; Rigg, J.; Tamang, S.; Paudel, K.P.; et al. Agricultural land underutilisation in the hills of Nepal: Investigating socio-environmental pathways of change. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 53, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duesberg, S.; Bogue, P.; Renwick, A. Retirement farming or sustainable growth–land transfer choices for farmers without a successor. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egidi, G.; Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir, R.; Cividino, S.; Quaranta, G.; Salvati, L.; Colantoni, A. Rural in Town: Traditional Agriculture, Population Trends, and Long-Term Urban Expansion in Metropolitan Rome. Land 2020, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.Z.; Hui, E.C.; Zhao, P.J.; Long, H.L. Land use policy for urbanization in China. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Jiang, Q.B. Land arrangements for rural–urban migrant workers in China: Findings from Jiangsu province. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; Guo, S.L.; Xie, F.T.; Liu, S.Q.; Cao, S. The impact of rural laborer migration and household structure on household land use arrangements in mountainous areas of Sichuan Province, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 70, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; Zhang, J.F.; Rasul, G.; Liu, S.Q.; Xie, F.T.; Cao, M.T.; Liu, E. Household livelihood strategies and dependence on agriculture in the mountainous settlements in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4850–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, M.T.; Xu, D.D.; Xie, F.T.; Liu, E.L.; Liu, S.Q. The influence factors analysis of households’ poverty vulnerability in southwest ethnic areas of China based on the hierarchical linear model: A case study of Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 66, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xu, D.; Qi, Y.; Zeng, M. Labor Off-Farm Employment and Cropland Abandonment in Rural China: Spatial Distribution and Empirical Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, X.; Xu, D.D.; Zeng, M.; Qi, Y.B. Does Labor Off-farm Employment Inevitably Lead to Land Rent Out? Evidence from China. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Xu, D.D.; Wang, X.X. Vulnerability of rural household livelihood to climate variability and adaptive strategies in landslide-threatened western mountainous regions of the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. ClimDev-Afr. 2019, 11, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.L.; Lin, L.; Wei, Y.L.; Xu, D.D.; Li, Q.Y.; Liu, S.Q. Interactions between Sustainable Livelihood of Farm household and Agricultural Land Transfer in the Mountainous and Hilly Regions of Sichuan, China. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; Deng, X.; Guo, S.L.; Liu, S.Q. Sensitivity of Livelihood Strategy to Livelihood Capital: An Empirical Investigation Using Nationally Representative Survey Data from Rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 144, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xu, D.; Zeng, M.; Qi, Y. Landslides and Cropland Abandonment in China’s Mountainous Areas: Spatial Distribution, Empirical Analysis and Policy Implications. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, D.D.; Deng, X.; Guo, S.L.; Liu, S.Q. Labor migration and cropland abandonment in rural China: Empirical results and policy implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xu, D.D.; Zeng, M.; Qi, Y.B. Does early-life famine experience impact rural land transfer? evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; Deng, X.; Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Yong, Z.L.; Liu, S.Q. Relationships between labor migration and cropland abandonment in rural China from the perspective of village types. Land Use Policy 2019, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.S.; Ye, C.; Cai, Y.L.; Xing, X.S.; Chen, Q. The impact of rural out-migration on land use transition in China: Past, present and trend. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Long, H.L. The process and driving forces of rural hollowing in China under rapid urbanization. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Li, Y.R.; Liu, Y.S.; Michael, W.; Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by increasing vs. decreasing balance land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolecka, N.; Kozak, J.; Kaim, D.; Dobosz, M.; Ostafin, K.; Ostapowicz, K.; Wezyk, P.; Price, B. Understanding farmland abandonment in the polish Carpathians. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 88, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.S.; Wang, H.M.; Cheng, Y.X.; Zheng, B.; Lu, Z.L. The impact of rural out-migration on arable land use intensity: Evidence from mountain areas in Guangdong, China. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.Z.; Yang, Z.Y.; Li, Z.H.; Li, X.B.; Xin, L.J.; Sun, L.X. Drivers of cropland abandonment in mountainous areas: A household decision model on farming scale in southwest China. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.B.; Song, W. Determinants of cropland abandonment at the parcel, household and village levels in mountain areas of China: A multi-level analysis. Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.Z.; Huang, J.K.; Rozelle, S.; Zhang, J.P.; Li, Z.H. Impact of urbanization on cultivated land changes in China. Land Use Policy 2015, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaquet, S.; Schwilch, G.; Hartung-Hofmann, F.; Adhikari, A.; Sudmeier-Rieux, K.; Shrestha, G.; Liniger, H.P.; Kohler, T. Does outmigration lead to land degradation? labour shortage and land management in a western Nepal watershed. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 62, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Li, Y.R.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y.S. Urban–rural transformation in relation to cultivated land conversion in China: Implications for optimizing land use and balanced regional development. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Wu, X.Q.; Wang, W.J.; Dong, G.H. Analysis of urban-rural land-use change during 1995-2006 and its policy dimensional driving forces in Chongqing, China. Sensors 2008, 8, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yan, X.H.; Bauer, S.; Huo, X.X. Farm size, land reallocation, and labor migration in rural China. Popul. Space Place 2014, 20, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.Q.; Qian, Z.H.; Zhang, L.X.; Zhang, T.L. Rural labor migration and households’ land rental behavior: Evidence from China. China World Econ. 2018, 26, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.K.; Gao, L.L.; Rozelle, S. The effect of off-farm employment on the decisions of households to rent out and rent in cultivated land in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2012, 4, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.T.; Xu, D.D.; Liu, S.Q.; Cao, M.T. The influence of gender and other characteristics on rural laborers’ employment patterns in the mountainous and upland areas of Sichuan, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.T.; Liu, S.Q.; Xu, D.D. Gender difference in time-use of off-farm employment in rural Sichuan, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y.; Yong, Z.; Xu, D. Does off-Farm Migration of Female Laborers Inhibit Land Transfer? Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Land 2020, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, D.; Ma, Z.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, K.; Zhou, W.; Yong, Z. Relationships between Land Management Scale and Livelihood Strategy Selection of Rural Households in China from the Perspective of Family Life Cycle. Land 2020, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liao, H.L. The part-time work of farmers and its impact on the use rights transfer of the agricultural land, China. Manag. World 2012, 5, 62–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z.H. Whether off-farm employment would inevitably lead to agricultural land transfer?—Based on the theoretical analysis on internal labor division of the family and the explanation for China’s rural household part-time employment. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2008, 10, 13–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.M.; Qian, W.R. Study on farmers’ willingness of land transfer under different levels of concurrent business: Based on the investigation and evidence in Zhejiang province, China. Issues Agric. Econ. 2014, 35, 19–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y. The development of the land lease market in rural China. Land Econ. 2000, 76, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Chen, L.G.; Shi, X.P. Empirical analysis on off-farm employment and rural household land use behavior: Allocation effect, part-time effect and investment effect—Based on the survey data of rural households in Jiangxi Province in 2005. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2010, 3, 41–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.D.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.X.; Liu, S.Q. Influences of labor migration on rural household land transfer: A case study of Sichuan Province, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.H. Concurrent business of farmers and its effects on circulation of rural lands in China: An analytical framework. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 8, 36–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.T. Analysis on the restrictive mechanism of rural households’ part-time employment on the scale management of agricultural land. Rural. Econ. 2012, 1, 49–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.R.; Yao, Y. Local versus global separability in agricultural household models: The factor price equalization effect of land transfer rights. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 84, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y. Off-farm employments and land rental behavior: Evidence from rural China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2015, 8, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xu, D.D.; Zeng, M.; Qi, Y.B. Does Internet use help reduce rural cropland abandonment? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Xu, D.D.; Zeng, M.; Qi, Y.B. Does Outsourcing Affect Agricultural Productivity of Farmer Households? Evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Zhang, H.Q.; Xie, F.T.; Guo, S.L. Current situation and influencing factors of pluriactivity in mountainous and hilly rural areas of Sichuan province, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2013, 10, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Xie, F.T.; Zhang, H.Q.; Guo, S.L. Influences on rural migrant workers’ selection of employment location in the mountainous and upland areas of Sichuan, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 33, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Heerink, N.; Ierland, E.V.; Shi, X. Land tenure insecurity and rural-urban migration in rural China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2016, 95, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.P.; Heerink, N.; Qu, F.T. Choices between different off-farm employment sub-categories: An empirical analysis for Jiangxi province, China. China Econ. Rev. 2007, 18, 438–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L. Land use policy in China: Introduction. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Tu, S.S.; Ge, D.Z.; Li, T.T.; Liu, Y.S. The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: Problems and prospects. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuntz, K.A.; Beaudry, F.; Porter, K.L. Farmers’ Perceptions of Agricultural Land Abandonment in Rural Western New York State. Land 2018, 7, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rząsa, K.; Ogryzek, M.; Źróbek, R. The Land Transfer from the State Treasury to Local Government Units as a Factor of Social Development of Rural Areas in Poland. Land 2019, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kung, K.S. Off-farm labor markets and the emergence of land rental markets in rural China. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 30, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Variable Specific Definition | Mean | SDc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||

| Rent In | Whether farmers have rent-in land (0=no;1=yes) | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| Rent Out | Whether farmers have rent-out land (0=no;1=yes) | 0.69 | 0.46 |

| Area rented in | Rent-in land area of farmers (mu a) | 1.25 | 14.20 |

| Area rented out | Rent-out land area of farmers (mu a) | 4.00 | 7.70 |

| Part-time employment | The ratio of part-time labor force to household total labor force (%) | 0.11 | 0.25 |

| Off-farm employment | The ratio of off-farm labor force to household total labor force (%) | 0.40 | 0.39 |

| Head age | Household head’s age (year) | 53.80 | 13.20 |

| Head education | Whether household head has received a high school diploma or above (0 = no;1 = yes) | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Household labors | Total household labor force (number) | 2.74 | 1.60 |

| Land area | Per capita contract land size of the household (mu a/person) | 1.67 | 1.97 |

| Agricultural assets | Per capita of current market value of all the agricultural assets that a household possesses (Wan Yuan b/person) | 0.08 | 0.53 |

| Fixed assets | Per capita of current market value of all the fixed assets that a household possesses (Wan Yuan b/person) | 4.32 | 16.75 |

| Variables | Probit Models for whether Farmers Have Rent-In Land | Probit Models for whether Farmers Have Rent-Out Land | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | ||

| Off-farm employment | −0.260 *** | −0.373 *** | −1.074 *** | −0.966 *** | −0.155 *** | 0.403 *** | 0.412 *** | 1.613 *** | 1.711 *** | 0.477 *** | |

| (0.058) | (0.067) | (0.155) | (0.172) | (0.032) | (0.047) | (0.050) | (0.408) | (0.178) | (0.047) | ||

| Part-time employment | −0.213 ** | −0.250 *** | −0.770 *** | −0.342 | −0.055 | 0.485 *** | 0.470 *** | 2.730 *** | 2.738 *** | 0.764 *** | |

| (0.086) | (0.094) | (0.175) | (0.223) | (0.036) | (0.074) | (0.077) | (0.440) | (0.230) | (0.062) | ||

| Head age | 0.057 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.008 *** | −0.055 *** | −0.036 *** | −0.010 *** | |||||

| (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.002) | (0.009) | (0.010) | (0.003) | ||||||

| Head age^2 | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||

| Head education | −0.022 | 0.019 | 0.003 | 0.024 | −0.026 | −0.007 | |||||

| (0.066) | (0.067) | (0.011) | (0.052) | (0.046) | (0.013) | ||||||

| Land area | −0.034 | −0.038 | −0.006 | 0.780 *** | 0.644 *** | 0.180 *** | |||||

| (0.068) | (0.114) | (0.018) | (0.129) | (0.102) | (0.028) | ||||||

| Household labors | 0.099 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.011 | −0.071 *** | −0.020 *** | |||||

| (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.003) | (0.011) | (0.015) | (0.004) | ||||||

| Ln(Fixed assets) | 0.025 | 0.043 * | 0.007 * | −0.050 *** | −0.062 *** | −0.017 *** | |||||

| (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.004) | (0.018) | (0.016) | (0.005) | ||||||

| Ln(Agricultural assets) | 0.953 *** | 0.865 *** | 0.139 *** | −0.890 *** | −0.374 *** | −0.104 *** | |||||

| (0.101) | (0.103) | (0.016) | (0.110) | (0.117) | (0.033) | ||||||

| Constant | −1.656 *** | −3.236 *** | −1.487 *** | −3.090 *** | 0.451 *** | 0.343 | −0.027 | −0.353 | |||

| (0.209) | (0.427) | (0.191) | (0.485) | (0.126) | (0.382) | (0.188) | (0.360) | ||||

| Province dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Instrumental variables | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Wald χ2 | 269.378 *** | 458.559 *** | 337.629 *** | 492.424 *** | 492.424 *** | 929.240 *** | 1002.882 *** | 2179.432 *** | 2373.026 *** | 2373.026 *** | |

| Endogenous Wald χ2 | 32.968 *** | 15.814 *** | 15.814 *** | 58.191 *** | 90.002 *** | 90.002 *** | |||||

| Observations | 7994 | 7994 | 7994 | 7994 | 7994 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | |

| Variables | Tobit Models for Rent-In Land Area of Farmers | Tobit Models for Rent-Out Land Area of Farmers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | Model 19 | Model 20 | ||

| Off-farm employment | −11.664 *** | −14.173 *** | −46.712 *** | −22.210 *** | −0.104 *** | 2.961 *** | 1.498 *** | 8.086 *** | 8.197 *** | 0.398 *** | |

| (3.706) | (3.609) | (15.144) | (5.767) | (0.027) | (0.250) | (0.217) | (1.520) | (0.586) | (0.024) | ||

| Part-time employment | −12.676 ** | −10.117 ** | −29.310 | −5.553 | −0.026 | 3.794 *** | 2.376 *** | 14.825 *** | 14.097 *** | 0.685 *** | |

| (5.630) | (4.320) | (20.752) | (7.973) | (0.037) | (0.436) | (0.374) | (1.827) | (0.715) | (0.029) | ||

| Head age | 2.181 ** | 1.187 *** | 0.006 *** | −0.215 *** | −0.186 *** | −0.009 *** | |||||

| (0.872) | (0.420) | (0.002) | (0.031) | (0.027) | (0.001) | ||||||

| Head age^2 | −0.024 *** | −0.014 *** | −0.000 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.000 *** | |||||

| (0.008) | (0.004) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||

| Head education | 3.669 | 1.805 | 0.008 | 0.388 | −0.212 | −0.010 | |||||

| (4.027) | (2.064) | (0.009) | (0.256) | (0.194) | (0.009) | ||||||

| Land area | −2.496 | −1.851 | −0.009 | 5.302 *** | 4.717 *** | 0.229 *** | |||||

| (2.546) | (1.678) | (0.008) | (0.372) | (0.349) | (0.017) | ||||||

| Household labors | 4.354 *** | 3.470 *** | 0.016 *** | 1.136 *** | 0.595 *** | 0.029 *** | |||||

| (1.098) | (0.544) | (0.002) | (0.062) | (0.045) | (0.002) | ||||||

| Ln(Fixed assets) | 1.235 | 1.543 ** | 0.007 ** | −0.100 | −0.281 *** | −0.014 *** | |||||

| (1.100) | (0.763) | (0.004) | (0.070) | (0.071) | (0.003) | ||||||

| Ln(Agricultural assets) | 64.083 ** | 32.508 *** | 0.151 *** | −4.325 *** | −1.765 *** | −0.086 *** | |||||

| (26.336) | (4.270) | (0.021) | (0.910) | (0.377) | (0.018) | ||||||

| Constant | −86.880 *** | −146.240 *** | −83.827 *** | −84.506 *** | 3.265 *** | −6.103 *** | 1.852 ** | −5.704 *** | |||

| (27.166) | (47.558) | (23.212) | (15.203) | (0.617) | (1.223) | (0.723) | (1.153) | ||||

| Province dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Instrumental variables | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Wald χ2 | 243.942 | 155.786 | 155.786 | 5007.226 *** | 1.3e+04 *** | 1.3e+04 *** | |||||

| Endogenous Wald χ2 | 156.493 | 549.125 | 549.125 | 156.493 *** | 549.125 *** | 549.125 *** | |||||

| Observations | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | |

| Variables | Robustness Check Models for whether Farmers Have Rent-in Land | Robustness Check Models for whether Farmers Have Rent-out Land | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure of Labor Transfer by Income (Probit) | Measure of Labor Transfer by the Number of Labor Force (IVreg) | Measure of Labor Transfer by Income (Probit) | Measure of Labor Transfer by the Number of Labor Force (IVreg) | ||||||

| Off-farm employment | −0.562 *** | −0.528 *** | −0.174 *** | −0.137 *** | 0.860 *** | 0.838 *** | 0.622 *** | 0.628 *** | |

| (0.066) | (0.069) | (0.038) | (0.037) | (0.051) | (0.052) | (0.066) | (0.067) | ||

| Part-time employment | −0.198 *** | −0.123 ** | −0.138 ** | −0.051 | 0.381 *** | 0.342 *** | 0.963 *** | 0.915 *** | |

| (0.048) | (0.049) | (0.067) | (0.067) | (0.040) | (0.041) | (0.104) | (0.104) | ||

| Province dummies | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Instrumental variables | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Control variables | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Wald χ2/F statistics | 321.762 *** | 463.774 *** | 12.071 *** | 14.651 *** | 1141.130 *** | 1170.545 *** | 45.090 *** | 45.194 *** | |

| Observations | 7994 | 7994 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | |

| Variables | Robustness Check Models Rent-in Land Area of Farmers | Robustness Check Models for Rent-out Land Area of Farmers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure of Labor Transfer by Income (Tobit) | Measure of Labor Transfer by the Number of Labor Force (IVreg) | Measure of Labor Transfer by Income (Tobit) | Measure of Labor Transfer by the Number of Labor Force (IVreg) | ||||||

| Off-farm employment | −29.124 *** | −23.316 *** | −0.353 *** | −0.231 *** | 3.636 *** | 3.411 *** | 1.042 *** | 1.071 *** | |

| (8.630) | (5.377) | (0.086) | (0.084) | (0.298) | (0.256) | (0.109) | (0.108) | ||

| Part-time employment | −11.738 *** | −6.383 ** | −0.488 *** | −0.228 | 2.033 *** | 1.615 *** | 1.928 *** | 1.831 *** | |

| (4.273) | (2.544) | (0.147) | (0.145) | (0.268) | (0.228) | (0.186) | (0.185) | ||

| Province dummies | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Instrumental variables | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Control variables | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Wald χ2/F statistics | 10.478 *** | 12.535 *** | 119.639 *** | 140.957 *** | 243.337 *** | 326.784 *** | |||

| Observations | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | 8031 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, D.; Yong, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhuang, L.; Qing, C. Rural-Urban Migration and its Effect on Land Transfer in Rural China. Land 2020, 9, 81. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/land9030081

Xu D, Yong Z, Deng X, Zhuang L, Qing C. Rural-Urban Migration and its Effect on Land Transfer in Rural China. Land. 2020; 9(3):81. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/land9030081

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Dingde, Zhuolin Yong, Xin Deng, Linmei Zhuang, and Chen Qing. 2020. "Rural-Urban Migration and its Effect on Land Transfer in Rural China" Land 9, no. 3: 81. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/land9030081