The Old Testament Prophecy of the Resurrection of the Dry Bones between the West and Byzantium

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The First Near-Eastern Pictorial Testimonies of the Iconographic Theme

Then he said to me: “Son of man, these bones are the people of Israel. They say, ‘Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off.’ Therefore prophesy and say to them: ‘This is what the Sovereign Lord says: My people, I am going to open your graves and bring you up from them; I will bring you back to the land of Israel. Then you, my people, will know that I am the Lord, when I open your graves and bring you up from them. I will put my Spirit in you and you will live, and I will settle you in your own land. Then you will know that I the Lord have spoken, and I have done it, declares the Lord.’”

3. Ezekiel’s Prophecy of the Dry Bones within Roman Sepulchral Plastic

4. Late Antique Occurrences of the Scene on Objects of Art

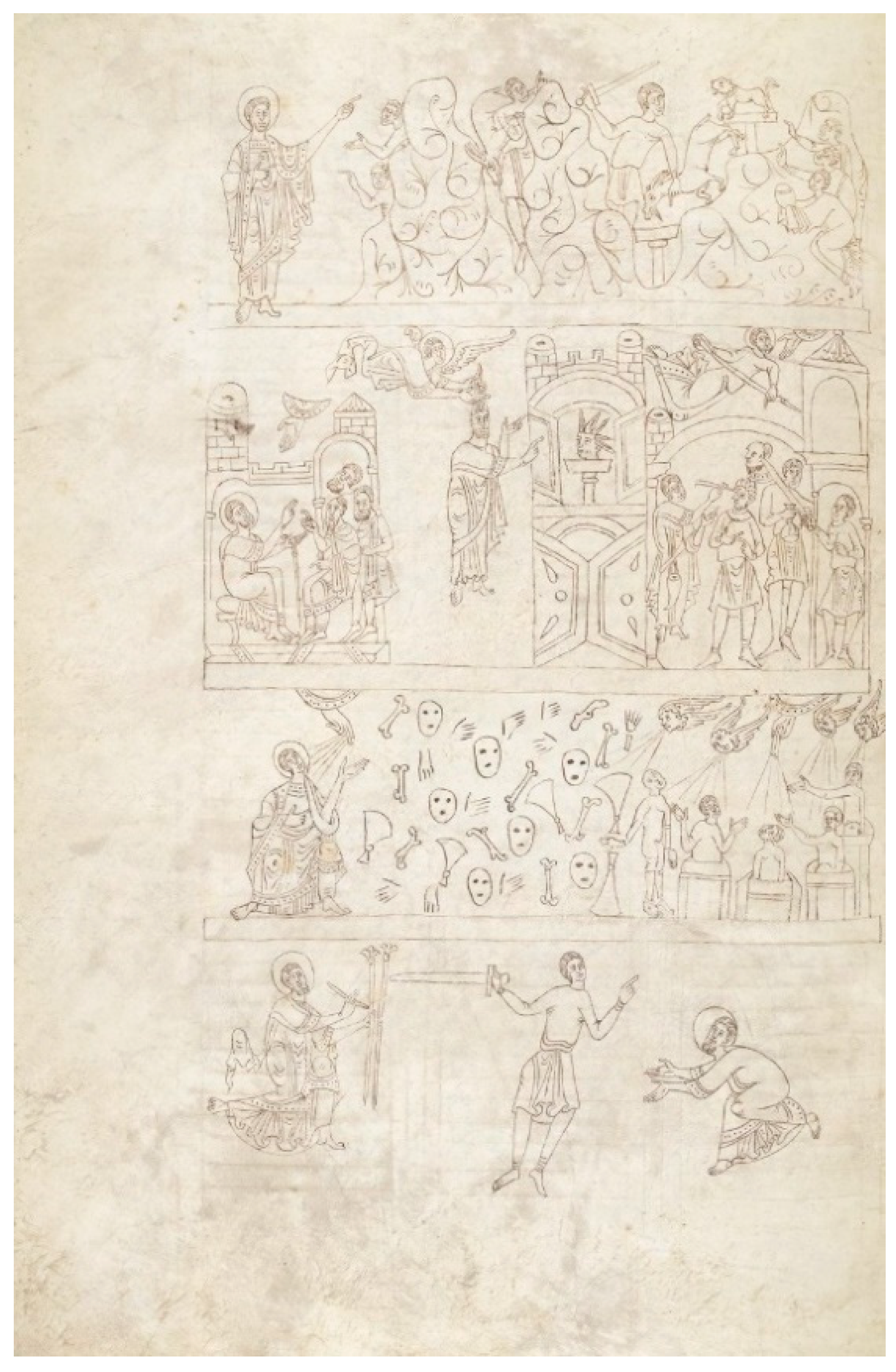

5. The Old Testament Prophecy in Illuminated Manuscripts between East and West

The hand of the Lord was on me, and he brought me out by the Spirit of the Lord and set me in the middle of a valley; it was full of bones. He led me back and forth among them, and I saw a great many bones on the floor of the valley, bones that were very dry.

This is what the Sovereign Lord says to these bones: I will make breath enter you, and you will come to life. I will attach tendons to you and make flesh come upon you and cover you with skin; I will put breath in you, and you will come to life. Then you will know that I am the Lord.

Then he said to me, “Prophesy to the breath; prophesy, son of man, and say to it, ‘This is what the Sovereign Lord says: Come, breath, from the four winds and breathe into these slain, that they may live.’” So I prophesied as he commanded me, and breath entered them; they came to life and stood up on their feet—a vast army.

K[ΥPΙ]E K[ΥPΙ]E HZHCETAΙ TA OCTA TAΥTA.

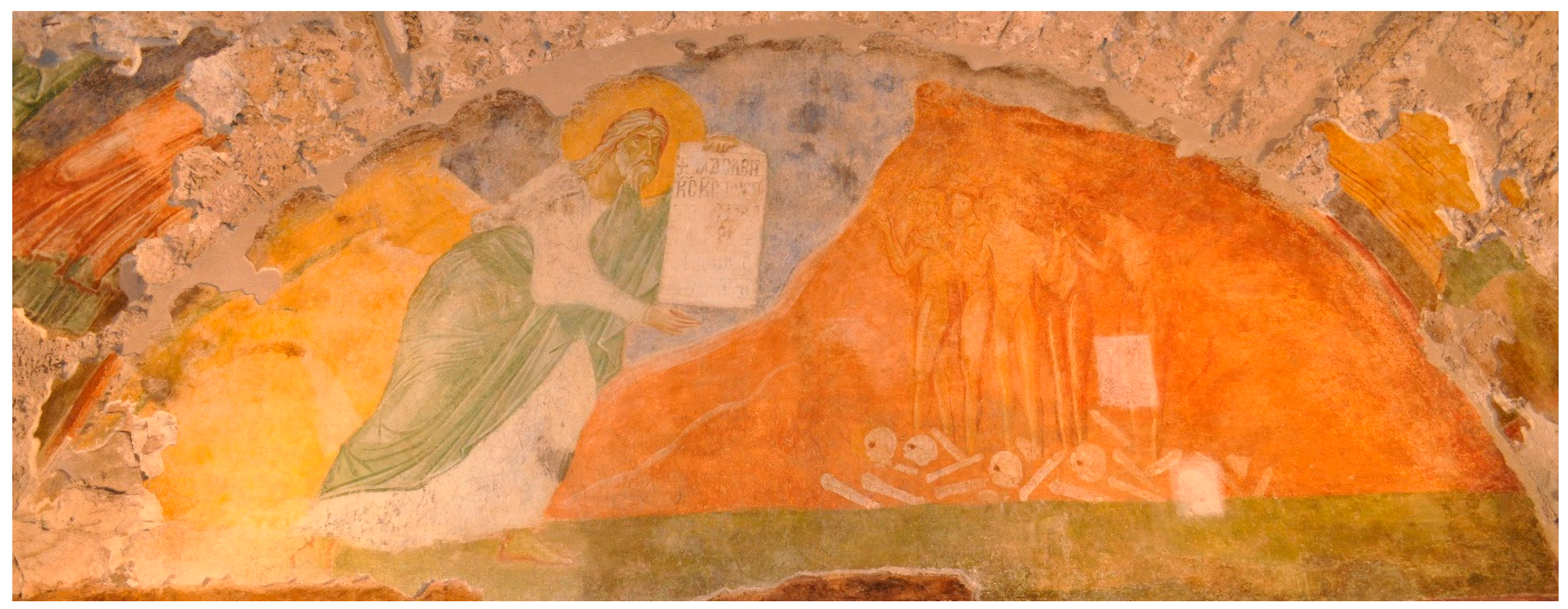

6. The Old Testament Prophecy in the Byzantine Monumental Monastic Decoration

Τάδε λέγει κύριος κύριος τοῖς ὀστέοις τούτ[οις ἰδ]ού,] ἐγώ φ[έρωεἰςὑ]μάς πν(εῦμ)α πν(εύμ)α [ζ]ωῆς

This is what the Sovereign Lord says to these bones: I will make breath enter you, and you will come to life.

I remember the prophet who said: I am earth and ashes and again I looked in the tombs, I saw the emaciated bones and I said: who is the king, or the soldier, who is the rich or poor, who is the righteous or the sinner? But rest with the righteous, Lord, Your servant!20

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babić, Gordana. 1969. Les chapelles annexes des églises byzantines. Fonction liturgique et programmes iconographiques. Paris: Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalova, Elka. 2003. The Ossuary of the Bachkovo monastery. Plovdiv: Pygmalion. [Google Scholar]

- Block, Daniel I. 1992. Beyond the Grave: Ezekiel’s Vision of Death and Afterlife. Bulletin for Biblical Research 2: 113–41. [Google Scholar]

- Brenk, Beat. 1966. Tradition und Neuerung in der christlichen Kunst des ersten Jahrtausends. Studien zur Geschichte des Weltgerichtsbildes. Vienne: Hermann Böhlaus. [Google Scholar]

- Caillet, Jean-Pierre, and Helmuth Nils Loose. 1990. La Vie d’éternité. La sculpture funéraire dans l’Antiquité chrétienne. Paris: Éditions du Cerf, Genève: Éditions du Tricorne. [Google Scholar]

- Castiñeiras, Manuel. 2020. Les bibles de Ripoll et Rodes et les ivoires de Salerne. La narration biblique appliquée à des supports varies: Modèles, adaptations et discours. In Les stratégies de la narration dans la peinture médiévale. La représentation de l’Ancien Testament aux IVe-XIIe siècles. Edited by Marcelo Angheben. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 67–100, 412–15. [Google Scholar]

- Contessa, Andreina. 2008. Nouvelles observations sur la Bible de Roda. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 51: 329–42. [Google Scholar]

- Contessa, Andreina. 2009. L’iconographie des cycles de Daniel et Ézéchiel dans les Bibles de Ripoll. Cahiers de Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa 40: 165–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, Anthony. 1992. Πᾶς οἶκος Ἰσραήλ. Ezekiel and the policy of resurrection in Tenth-Century Byzantium. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 46: 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waal, Anton. 1906. Die biblischen Totenerweckungen an den altchristlichen Grabstätten. Römische Quartalschrift für christliche Altertumskunde und Kirchengeschichte 20: 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrievskij, Alexei. 1965. Oпиcaниe литypгицecкиx pyкопиceй. Hildesheim: Georg Olms. [Google Scholar]

- Du Mesnil du Buisson, Robert. 1939. Les peintures de la synagogue de Doura-Europos, 245-245 après J.-C. Rome: Pontificio Istituto Biblico. [Google Scholar]

- Galadza, Peter. 2004. The Evolution of Funerals for Monks in the Byzantine Realm. From the Tenth to the Sixteenth Century. Orientalia Christiana Periodica 70: 225–57. [Google Scholar]

- Garrucci, Raffaelle. 1879. Storia della arte cristiana nei primi otto secoli della chiesa: Corredata della Collezione di tutti i monumenti di pittura e scultura; incisi in rame su 500 tavole ed illustrati. Vol. 5: Sarcofagi ossia sculture cimiteriali. Prato: Gaetano Guasti. [Google Scholar]

- Goar, Jacobus. 1647. Euchologion sive situale graecorum. Complectens ritus et ordines divinae liturgiae, officiorum, sacramentorum, consecrationum, benedictionum, funerum, orationum, & juxta usum orientalis ecclesiae. Paris: Simeon Piget. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, Joseph A. 1965. Ezekiel XXXVII 1-14 and the New Testament. New Testament Studies 11: 162–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, Moshe. 1997. Ezekiel 21-37. A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume, Denis. 1992. Grand euchologe et arkhiératikon. Parma: Diaconie Apostolique. [Google Scholar]

- Keser-Kayaalp, Elif. 2010. The Beth Qadishe in the Late Antique Monasteries of Nothern Mesopotamia (South-Eastern Turkey). Parole de l’Orient 35: 325–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kittel, Gisela. 1999. Befreit aus dem Rachen des Todes. Tod und Todesüberwindung im Alten und Neuen Testament. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Kotoula, Dimitra. 2006. Founding for Salvation. The Burial Chapel of the Founder in Byzantine Monastic Institutions and Its Decoration. Ph.D. thesis, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kraeling, Carl H. 1956. The Excavations at Dura Europos. Final Report VIII. Part I. The Synagogue. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, Jules. 1964. Les manuscrits syriaques à peintures conservés dans les bibliothèques d’Europe et d’Orient. Contribution à l’étude de l’iconographie des églises de langue syriaque. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. [Google Scholar]

- Maltzew, Alexios V. 1898. Begräbniss-Ritus und einige specielle und alterthümliche Gottesdienste der orthodox-katholischen Kirche des Morgenlandes. Deutsch und slawisch unter Berücksichtigung des griechischen Urtextes. Berlin: Karl Siegismund. [Google Scholar]

- Mango, Cyril, Ernest J. W. Hawkins, and Susan Boyd. 1990. The Monastery of St. Chrysostomos at Koutsoventis, Cyprus, and its wall paintings. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 44: 63–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzerath, Paul. 1939. Die Totenfeiern der byzantinischen Kirche. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. [Google Scholar]

- Mundell, Maria C. 1975. A sixth-century funerary relief at Dara in Mesopotamia. Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik 24: 209–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mundó, Anscari M. 2002. Les Bíblies de Ripoll:’ estudi dels Mss. Vatica, Lat. 5729 i París, BNF, Lat.6 Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, Col. Studi e testi, 408. Citta del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Nauerth, Claudia. 1980. Vom Tod zum Leben. Die christlichen Totenerweckungen in der in der spätantiken Kunst. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Nelidow, Alexandre, and Antoine Nivière. 1979. Euchologe ou Rituel de l’Église orthodoxe. Le Bousquet-d’Orb: Monastère orthodoxe Saint-Nicolas de la Dalmerie. [Google Scholar]

- Neuss, Wilhelm. 1912. Das Buch Ezechiel in Theologie und Kunst bis zum Ende des XII. Jahrhunderts mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Gemälde in der Kirche zu Schwarzrheindorf. Ein Beitrag zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Typologie der christlichen Kunst, vornehmlich in den Benediktinerkloestern. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Neuss, Wilhelm. 1915. Ikonographische Studien zu den Kölner Werken der altchristlichen Kunst. Zeitschrift für christliche Kunst 28: 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- Omont, Henri. 1909. Peintures de l’Ancien Testament dans un manuscrit syriaque du VIIe ou du VIIIe siècle. Monuments et Mémoires Publiés par l’Académie des Inscriptions et des Belles-Lettres 17: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacostas, Tassos, Cyril Mango, and Michael Grünbart. 2007. The History and Architecture of the Monastery of St. John Chrysostom at Koutsoventis, Cyprus. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61: 25–156. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, Athanasios. 2010. Christian Art in the Turkish-Occupied Part of Cyprus. Nicosia: The Holy Archbishopric of Cyprus. [Google Scholar]

- Parani, Maria G. 2018. A Monument of his own? An Iconographic Study of the Wall Paintings of the Holy Trinity Parekklesion at the Monastery of St. John Chrysostom, Koutsovendis (Chypre). Studies in Iconography 39: 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- Philonenko, Marc. 1994. De Qoumrân à Doura-Europos: La vision des ossements desséchés (Ézéchiel 37, 1–4). Revue D’histoire et de Philosophie Religieuses 74: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchette, Yoanna. 2019. За иконографията на една старозаветна "теофания" от Бачковската костница: видението на пророк Езекиил при река Ховар / About the iconography of an Old Testament theophany: Ezekiel‘s vision of God by the Kebar river. In ПАМЕТ НАСЛЕДСТВО КУЛТУРА (Етноложката перспектива) / MEMORY-HERITAGE-CULTURE (The ethnological perspective). Edited by Annual of “Ongal” Association of Anthropology, Ethnology and Folklore Studies. Sofia: Rod, vol. 18, year XIII. pp. 324–32, 441–71. [Google Scholar]

- Planchette, Yoanna. 2020. La chapelle médiévale du monastère de Bačkovo (Bulgarie). Un monument exceptionnel reconsidéré. Paris: L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, Adele. 1913. Beiträge zu einer Ikonographie des Todes. Ph.D. thesis, University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France. [Google Scholar]

- Sörries, Reiner. 1991. Die Syrische Bibel von Paris. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, syr. 341. Eine frühchristliche Bilderhandschrift aus dem 6. Jahrhundert. Wiesbaden: Reichert. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann, Kurt, and Herbert L. Kessler. 1990. The Frescoes of the Dura Synagogue and Christian Art. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzmann, Kurt. 1977. Spätantike und frühchristliche Buchmalerei. München: Prestel. [Google Scholar]

- Wilpert, Joseph. 1932. I Sarcophagi christiani antichi. Roma: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana. [Google Scholar]

- Wischnitzer-Bernstein, Rachel. 1941. The conception of the Resurrection in the Ezekiel Panel of the Dura Synagogue. Journal of Biblical Literature 60: 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | For a brief historical overview of this matter, see: (Kittel 1999, chp. 8 “Hesekiels Vision von der Auferweckung der Totengebeine”, pp. 69–72). |

| 2 | The Biblical citations in this paper come from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible (NRSV), available online at: https://www.biblegateway.com/. |

| 3 | We forward here to some digitalized material: Garrucci (1879), pl. 312, 1: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/garrucci1879bd5/0185; 313, 4: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/garrucci1879bd5/0186; 318, 1: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/garrucci1879bd5/0191; 361, 1: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/garrucci1879bd5/0234; 372, 2: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/garrucci1879bd5/0245; 376, 4: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/garrucci1879bd5/0249; 398, 3: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/garrucci1879bd5/0271. For other pertinent examples, see the doctoral thesis of Adele Reuter which is the first attempt to establish a “death iconography” with respect to early Christian art: (Reuter 1913, pp. 45–48, with earlier bibliography on the topic). For the abundant bibliography on Roman funerary plastic, see particularly: (Caillet and Loose 1990, p. 58, note 55, fig. 47; Neuss 1912, pp. 142–52, pl. 1–8; Brenk 1966, pp. 152–54, pl. 2, 53–55; Wilpert 1932, pp. 269–70, pl. CXII/2, CXXIII/3, CLVI, CLXXXIV/1, CCVI/7, CCXV/7, CCXIX/1; Nauerth 1980, pp. 82–89 (Totenerweckungen mit der Bildformel “nackter Leichnam” und einzelnem toten Kopf; Totenerweckungen mit “Gebein”; Totenerweckungen “en masse”), figs. 60–70). |

| 4 | For certain authors, like De Waal, the old Christian funerary art has conserved not a single Old Testament representation: (De Waal 1906, pp. 27–48 (most particularly pp. 28–31)). |

| 5 | For complete bibliographic references and digital reproduction of this object, see: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_S-317. |

| 6 | For the digitalized copy of this manuscript, see: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10527102b. |

| 7 | For a complete bibliography, as for the Catalan Bibles with a schematic of the questions of iconography and attribution, see: (Contessa 2008, pp. 329–42). |

| 8 | For a complete bibliographic list, see the BnF data: https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc620519. |

| 9 | For the digitalized copy of the volume, see: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b85388130. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | For a brief résumé of the exegetical dimension of the Old Testament prophecy, with special emphasis on Cyril of Alexandria, Theodoret of Cyrus, Ambrose and Tertullian, see: (Planchette 2020, pp. 239–42). |

| 12 | See the link to the digitized version of the manuscript: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.5729/0420. |

| 13 | For a complete bibliography on this Latin bible: http://gateway-bayern.de/BV040355440 and particularly the description of the Latin manuscripts in the Erlangen University Library by Hans Fischer (Ms. 1): http://www.manuscripta-mediaevalia.de/dokumente/html/hsk0601a A link to the digital copy of the Erlangen manuscript: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bvb:29-bv040355440-2. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | For more on the vision of the Glory of the Lord on the Kebar River, see: (Planchette 2019, pp. 324–32, 441–71; 2020, pp. 188–97, (with a complete bibliography on this topic)). |

| 16 | For the digitalized copy, see: https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc23564t and https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84522082. |

| 17 | Deesis: the supplication of the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist before the Christ for the salvation of the mankind. |

| 18 | For an in-depth review of the Ezekiel’s vision of the resurrection of the bones in the Bačkovo cemetery chapel, from iconographical and liturgical point of view, with a comparison to its visual environment, see: (Planchette 2020, pp. 227–31, 237–47, 257–59, 277–81 and especially pp. 387–90). |

| 19 | Missals containing the whole ceremonies celebrated at different occasions of the liturgical year. |

| 20 | Translation after: (Nelidow and Nivière 1979, p. 131; Guillaume 1992, p. 274 (“funérailles d’un moine ou d’une moniale”); Matzerath 1939, p. 88 (“Totenfeier für Mönche”); Maltzew 1898, pp. 176–77 (“Ordnung des Begräbnisses der Mönche”)). |

| 21 | Eumathios Philokales, governor of Cyprus. |

| 22 | See the rapport, which includes the photos taken during the restoration efforts carried out in the 60s: (Mango et al. 1990, pp. 63–94). |

| 23 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Planchette, Y. The Old Testament Prophecy of the Resurrection of the Dry Bones between the West and Byzantium. Arts 2021, 10, 10. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/arts10010010

Planchette Y. The Old Testament Prophecy of the Resurrection of the Dry Bones between the West and Byzantium. Arts. 2021; 10(1):10. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/arts10010010

Chicago/Turabian StylePlanchette, Yoanna. 2021. "The Old Testament Prophecy of the Resurrection of the Dry Bones between the West and Byzantium" Arts 10, no. 1: 10. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/arts10010010