1. Introduction

This essay considers criticism not primarily as a written practice constructed externally to art, but as a lingering, if not necessarily revivified condition of contemporary artmaking. As an example of art criticism, at least in part, the essay is influenced by my own artistic practice and work as an independent gallerist and curator, although it does not describe these. In terms of the theoretical perspectives it interrogates, it is therefore partisan and invested, rather mythically ‘objective’ and disinterested. The essay is split into three sections. The first two shorter interconnected parts ‘set the scene’ for the third, which is the primary focus. Part one begins by citing the foundational critical precedent of art practiced negatively

against the world as it is. This tendency, evident in the practices of numerous avant-gardes, was intensely theorised by Theodor Adorno in particular. While by no means avoiding negativity, both philosophical and artistic criticality was opaque and emphatically textual under postmodernity. With postmodernity’s waning as an “episode in the history of criticism [that] enlivened theoretical debates for little more than twenty years” (

Osborne 2018, p. 3), its variegated languages were more recently replaced by the language of ‘the contemporary’, a permanent inescapable ‘now’ and futureless present (

Cusset 2016). ‘The contemporary’, as we understand and experience it, is crucially conditioned by the escalation of neoliberal values, and neoliberalism’s attendant naturalisation of circulatory capital as financialisation. Rather than discursive, ‘the economy’ under these circumstances, assumes an unavoidable

ambience that pervades and penetrates every aspect of life, including art. Neoliberalism effectively transforms the ideology of ‘economics’, its motivational imperatives and language, into contemporaneity’s

only reality (

Fisher 2009). Despite deep economic crises, many examples of contemporary art aspire to side with the signifiers of luxury and material excess. Whilst often cloaked in critical language (that usually operates primarily as marketing), such work is ultimately distinguished by its ambivalence. It becomes increasingly difficult to tell whether art of this genre, of which there is always more, is not really wholly endorsing of neoliberalism’s fetishisation of ‘economics’ as a master narrative (with all its attendant mounting excesses) within art as everywhere else (

Jelinek 2013;

Joselit 2013).

If the ambience of capital furnishes the exterior ambience and ‘ecology’ within which artists work, then the interfaces of social media constitute its interior. Part two focuses on how, because neoliberal values have been so successfully naturalised, the artist’s identity online internalises these. Social media is distinguished by relentless self-entrepreneurial interaction that activates the artist’s entire ‘natural’ life as commodity (

Berry 2018;

Bröckling 2016). The biopolitics of this scenario coincides with the artist’s functioning effectively as individual ‘enterprise-unit’ (

Foucault 2011). The seemingly inextricable enmeshing of the Self with the technologies of its relentless promotion poses a serious challenge to the concept of art as a potentially critical practice. Now the individual artist, seemingly devoid of options for collective solidarity, is permanently called to attention remotely as subject

and object. The artist’s entire persona is inextricability determined by their constantly ‘willing’ self-optimisation (

Châtelet 2014). In a climate of undying competition, it becomes almost impossible to extract artistic intention from the narcissistic intention to rise above all (

Lorrusso 2019). Even contemporary work by artists who have self-consciously embraced the aesthetics, ritualised language and practices associated with the internet and social media, it is equally notable for its ambivalence: is it a celebration, a joke or does it represent a canny, knowing alliance with the corporatised orientations that largely determine success today?

The naturalisation of the economy and neoliberal market values and their essentially affirmational biopolitical internalisation via dominant ‘social’ technologies, is currently facing a serious crisis. The capitalist crisis is clearly evidenced by the fact that while wages have been stagnant for decades and global economies are currently plummeting into severe recession heavily impacted by the effects of the COVID-19 virus, stocks are rising: the real economy has been de-hinged from the financial speculation of wealthy elites (

Varoufakis 2020). Meanwhile, the idea of the internet and social media as neutral tools for individual and social betterment have been cast into extreme doubt

1. Lastly, documentation of current environmental collapse as a result of the impact of global climate change mounts exponentially (

Illner 2021;

Malm 2020;

Buck 2019;

Stensrud and Eriksen 2019). With this in mind, section three considers the economic and institutional ramifications of what might be called a ‘revenge of nature’ in lieu of the actual biological challenge posed by the emergence of COVID-19 alongside the looming impacts of climate change. In both cases, ‘real nature’ returns, acting as an intensely critical agent without agency (being empty of subjectivity) of the effects of the current economised state of the world. This scenario dramatically exposes the significant limits and weaknesses of neoliberalism’s naturalised ‘economisation of everything’ structurally dependent on unending positivist expansion within the artworld as everywhere else. Art as critique at its most incisive, of which numerous examples are cited, rather than simply illustrate these conditions and their effects (although this happens more and more), becomes implosive: it deflects core aspects of neoliberalism’s systems of affirmation and valorisation and turns them against itself. It is a negative move in a properly critical sense but one that does not overstate art’s agency as the historical avant-gardes at times did. In fact, critical art of this kind is ‘self-annulling’ (

Agamben 1999); it ‘disappears’ itself, emphasising instead its potential as a conduit for action and signification beyond the confines of art. With the permanent injunction to ‘make the most of one’s self’ while trapped within a coercive system naturalised as inevitable, forever seeking to recoup all capital potential, maybe art’s most critical gestures are those that pre-empt its ‘un-doing’: refusing to heed the endless call to productivity, escaping and actively withdrawing from its most complicit manifestations, tactically pursuing ‘lines of flight’ (

Deleuze and Guattari 1980) rather than conceding to the domination of financialised jargon or simply ‘giving up’.

2. It’s Only Natural: The Ambience of Capital and the Ambience of Critique

What was once considered a keystone of the critical project, negativity is anathema to neoliberal society (less a society than an inescapable economic imposition). Negativity, central to formational notions of critique, appears to have abandoned much ‘mainstream’ contemporary art. Today, criticism, contrasting to perennially triumphalist neoliberal jargon which at its most self-congratulatory had claimed to have achieved ‘the best possible solution to the problem of human existence’ (

Fukuyama 1992), can simply sound like whining. Criticism is what gets in the way of ‘living your best life’. According to neoliberalism’s positivist dictates: “It follows that the entire negativity spectrum—from sadness to fear, and including cynicism and anger—is inadmissible and intrinsically destructive […]; criticism is tolerated, but only of the

constructive kind, that is, criticism devoid of negativity” (

Lorrusso 2019, p. 131). For the Frankfurt School as the birthplace of so-called critical theory, and for Theodor Adorno in particular, the principal of negativity was paramount. Adorno’s ‘negative dialectics’ aimed to rescue the idealism of Hegelian dialectics from what he believed was its false positivity (

Adorno 1966). Hegel’s dialectics, although having “unleashed the all-destructive power of negativity” (

Žižek 2019, p. 1), always presumed a ‘greater outcome’ once internal contradictions had been sublated. Recourse to critique as negativity however was not a reactionary closing-off or shutting-down of discourse. It was an attempt to draw philosophical thinking closer to an

essential reality by focusing on the dialectical dimension of

thought itself (and not just relations between things and events external to it) (

Holloway and Tischler 2009). Negativity—the recognition that everything encompasses its own negation—could not be simply wished away. Nor could it be instrumentalised as utility and predictably put to ‘good use’.

Of course, the type of negativity theorised by Adorno was quite distinct from the variety of critical trajectories developed under postmodernity. By no means discounting or avoiding negative ‘content,’ what was notable about the extremely differentiated varieties of postmodernist critique was their opacity, complexity and fundamental textuality: no socio-cultural phenomena should ever be dismissed as obvious and given. Criticism was work that demanded the active work of the reader. There was no easy solution, no short cuts, and no point from which one could simply sit back and ‘appreciate the view.’ There are far too many related examples that are well-known to justifiably mention in this context, suffice to say that what marks ‘High Postmodernity’ is the labyrinthine opacity of its complex and variegated thinking. For some, this amounted to nothing but an overriding perception of it as ultimately impenetrable. Referring to the (onerous sounding) contemporary task of teaching Nietzsche, whose revival is intimately linked to the impetus of postmodernity, Mark Fisher writes, “Some students want Nietzsche in the same way that they want a hamburger; they fail to grasp—and the logic of the consumer system encourages this misapprehension—that the indigestibility, the difficulty

is Nietzsche” (

Fisher 2009, p. 24).

What is certain is that the overtly discursive and textual interpellation of culture and history changed after 1989 with the collapse of the Soviet bloc that signalled a “starting point of a gradual disintegration, in which a global economic system […] co-opted positions of criticality”. (

Kuzma 2010, p. 232). Frederick Jameson in his seminal 1991 book

Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism proposed that postmodern culture, being resolutely anti- or ‘a-’ dialectical was thus

the representative embodiment of a supposedly frictionless financialised capitalism. Jameson pointedly observed that it was now ‘easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism’ (

Jameson 2013). And yet, “when Jameson first advanced his thesis about postmodernism, there were still, in name at least, political alternatives to capitalism” (

Fisher 2009, p. 8). Soon after, this was not the case.

The shift from the languages of postmodernity to the language of ‘the contemporary’—extremely evident within art criticism

2—marked at the same time the shift from an array of historically attuned discourses to those permanently fixated on the ‘now’ as an eternal, inescapable present. This present was distinguished by “our unprecedented inability to think the future” (

Cusset 2016, p. 63). The endless ‘now’ is fundamentally conditioned by the accelerated domination of neoliberal economic practices and language. The attendant dematerialising financialisation of the global economy stresses the potential economic utility of all things and all experience (

Jappe 2017). Mark Fisher has famously referred to the contemporary condition in which we find ourselves according to the descriptor ‘capitalist realism

3’ where the thoroughly integrated language and practices of finance and the economy constitute the only perceivable reality of the age. Any suggestions of alternatives to capitalist example are frowned upon as impossible, ill-informed, naive, utopian, unworkable, foolish, dangerous or just plain unrealistic. At the same time, the neo-classical imperatives of neoliberalism that proclaim that societies can be run according to the exactitude of numerical calculation, conceal its fully ideological dimension. In fact, “There was more ideology in the 1990s’ lyrical odes to economic globalisation and to generalised self-regulation than during the entire Cold War” (

Cusset 2016, p. 44). ‘The Economy’, as it is relentlessly invoked, is thereby naturalised as a type of ambience that informs and inflects thoughts, daydreams, experience, every decision and every life choice—“ideology is ‘in the air’” (

Cusset 2016, p. 45) whilst financialisation, “reaches intensively into daily life, into social relationships and into the realms of subjectivity” (

Haiven 2018, p. 121). Neoliberalism “is a pervasive

atmosphere […an…] invisible barrier constraining thought and action” (

Fisher 2009, p. 16).

The naturalisation of a fully economicised contemporaneity is further facilitated by the shift of the economy into a largely spectral ‘atmospheric’ version of its already highly abstracted forms. Under conditions of financialisation, the “ambient disciplinary power of money” (

Haiven 2018, p. 148) is predominantly digital, and economic calculation and investment, mainly speculative in their activation of ‘fictitious capital’ (

Marx 1894). Increasing varieties of financial derivatives generate virtual value within circulation, ‘the economy in motion’ as a type of unending inward-turning spiral (

Harvey 2019). Characteristically, they are not attached to any physical product or commodity (

Harvey 2019;

Bröckling 2016;

Lazzarato 2011;

Marazzi 2011).

What this means for art potentially practiced as critique is various. In fact, the naturalised atmosphere of capitalism, as a phenomenon that is felt, thought and lived but which remains unlocatable, being everywhere and nowhere simultaneously, is echoed by contemporary art in which a ‘critical ambience’ or what might be called, the

aura of critique, predominates. Such work may routinely cite urgent contemporary social and/or political issues and events, sourcing images and text from news media and other journalistic or documentary sources. Yet often art of this ilk avoids entirely (unlike that of an earlier generation of ‘institutionally critical’ practitioners like the German/American artist Hans Haacke), extending the ramifications of its critical focus to the institutional contexts in which it is exhibited (

Steyerl 2012). Unlike its art-historical counterparts, this type of post-conceptualism appears to demand surprisingly little of the viewer (other than their registering something like the ‘appearance of intelligence’). It is a prevalent type of art recently parodied pointedly by contemporary American artist Charles Lutz in his series of works that are based on the

New Yorker’s cartoons but with the addition of new texts (

Figure 1). Here, a well-dressed man and woman converse at an art opening, where the woman tells the man that “their conceptual art process starts where thinking ends…”. Whilst ostensibly ‘conceptual’, Maurizio Catalan’s work appearing at the 2019 art fair

Art Basel Miami Beach, a work titled “Comedian”, composed of a banana duct-taped to the wall, sold for

$120,000 and typically generated a predictable welter of negative press about contemporary art and art fairs (

Elbaor 2019). Yet this work is not so much daring or questioning of the object or mechanisms of value generation within the art world, but wholly banal in its presentation of these as already known and eminently knowable. Moreover, it is a gesture entirely expected of that artist, like his equally reported solid gold toilet

America, from 2016 (among its layers of meaning it suggests a mock-Freudian bathos): ‘to the art world what the art world’s is’.

In other instances, rather than directly addressing its effects and impact, contemporary art seeks ever more ways to draw symbolically proximal with capital. It does so in one of two ways: it may present itself overtly as a natural object for elite collecting by physically indulging all the most obvious signifiers of wealth and value—significant scale, rare and expensive ‘luxury’ materials, a hefty price tag—or it may invoke economised conditions in an ostensibly ‘critical’ light. There are very many examples of the latter, some others of which I shall turn to in due course, but in the context of this argument such work is notable ultimately for its ambivalence. While evoking the ambience of a world wholly saturated with economic language, entrepreneurial values and ambitions, it is unclear whether such work is critically ironic or ultimately celebratory of the financialised circumstances of the present.

Consider Swiss artist Sylvie Fleury’s amassed ‘found-object’ ensembles of haute couture shopping bags and other prized fashion commodities with brand name labels clearly displayed. The kitsch garishness of their collective affect might be read as an indictment of the fetishistic pull such objects have on those who can afford them but, perhaps even more forcefully, on those who never could. Is such work a sardonic commentary on class inequality? Some of the artist’s own statements contradict this absolutely sounding like unapologetic identifications with global commodity culture: “I urge the audience to enjoy! Whatever they must do to get their kicks” (

Fleury 2002, p. 154). Tellingly, a website like Artsy.net, which also operates as an online auction house, declares Fleury’s work as having ‘blue-chip representation’ and lists works currently for sale alongside an inventory of recent auction results. At the same time, Artsy states that Fleury, “creates seductive objects and multimedia installations that, although they might be mistaken as endorsement, present a subtle commentary on the superficiality of consumer society and its values [whilst] referencing Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades and Andy Warhol’s obsession with shopping

4”. The contextual irony of this juxtaposition is clear in lieu of the undeniable severity of current capitalist crises. Moreover, an artist like Damien Hirst, whose work appears at times to critically target notions of value, both artistic and monetary, ends up in the cul-de-sac of banal literalism. What could be less expositionary or unremarkable in a climate of wall-to-wall predatory capitalist speculation than Hirst’s ‘notorious’ diamond skull from 2007 jokily titled “For the Love of God?” Priced at 50 million dollars, the work’s ultra-expensive kitsch excess intended to be provocatively ‘challenging’ as the world’s “most expensive artwork in history” (

McKee 2019, p. 137) is underscored by historical examples that question the ascription of value in art. In the end, however, Hirst simply illustrates, by example, the ‘natural’ state of a financialised world and art world (at least at its elite upper echelons), just as it is.

Although by no means on the same register of questionability as the previous examples, in 2020 Mexican-born, Swiss and London-based artist Stefan Brüggemann also presented a body of work ostensibly about the contemporary ambiguities of value.

Untitled Action: Gold Paintings was a series of gold-leaf paintings supposedly offering a “caustic perspective on modernity and the digital age

5”. These were advertised on Hauser and Wirth’s website and social media as having been explicitly produced entirely during lockdown

6. As such, they also subtly signalled a romantic, irrepressible artistic heroism in face of the anxiety-inducing backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Hauser and Wirth, Brüggemann’s practice more generally “sits outside the canon of the conceptual artists practicing in the 1960s and 1970s, who sought dematerialisation and rejected the commercialisation of art. Instead, his aesthetic is refined and luxurious, whilst maintaining a punk attitude

7”. Regardless of the artist’s intentions, in this case it his dealer’s claims for them that clearly seek to mitigate signifiers of wealth, goldness and abundance, with the legitimising language of a difficult to locate, “acerbic social critique

8”. Brüggemann himself speaks “of how gold fluctuates between being an economic power and a spiritual power. These fluctuations during this time of uncertainty, question its real value”.

9 He does not go on to analyse how this questioning operates or for what purpose. This exhibition took place at Hauser and Wirth’s St Moritz gallery, in a town otherwise renowned as a luxury resort destination. Although one might expect it to be an automatic consideration, it is surprising that this questioning of value and its meaning did not appear to have simultaneously translated to a contextual questioning, during “the greatest crisis [the] gallery … ever faced” (

Mun-Desalle 2020) of the wealth and privilege of one of the contemporary art world’s four richest commercial galleries

10 (

Morris 2019). What is the ‘spiritual’ transmutation of value in artworks sold predominantly to wealthy private collectors? The fetishistic signification of gold cannot be underestimated. From a Marxist perspective, it represents the conversion, as if by magic

11 (or alchemy), of manual and intellectual labour into commodities, in this instance implicitly signifying ‘money’ (gold) as the ultimate serialised abstraction (

Toscano 2019).

It is revealing to contrast this work, produced under present conditions of neoliberal financialisation, to works explicitly interrogating value from a slightly earlier period. In 1957, Yves Klein exhibited a series of eleven blue monochromes in

Arte Nucleare at the Galleria San Fedele in Milan. Although these paintings were “identical in size and appearance” (

Stich 1994, p. 87), the artist ascribed different prices to them. Through the medium of art, this series appears to reverse the logic of capitalist exchange which relies on money’s acontextual sameness; money, regardless of denomination, functions identically as symbolic value in all contexts. (

Vischmidt 2019). In Klein’s monochromes, of which there was also a slightly later gold series the artist called “Monogolds”, it is the art that is the same and the monetary values that are different, for no apparent logical reason. Heightened and furtive capitalist competition promoted in the art market, particularly through auctions that aim to determine hierarchies of value, is symbolically confounded when presented with works produced during the same period that look the same but cost different amounts. By “assimilating value to value plain and simple” (

De Duve and Krauss 1989, p. 78), Klein openly questioned the standardised capitalist logic of valuing art (Stich: p. 87).

Consider an ambiguous and intractable gesture by Belgian ‘institutionally critical’ conceptualist Marcel Broodthaers, which also interrogates the ambiguities of financialised value within art. As part of the ‘department of finance’ of his greater para-fictional project, the “Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles” (1970–1971), Broodthaers’ had a series of identical gold bars stamped with an eagle emblem. He pronounced that henceforth the price of each ingot was double; half their value was calculable by its physical weight in gold and the other by its value as art. Via this superficially simple move a constellation of associated readings and suggestions arise; the controversial contemporary de-pegging of the US dollar from the international gold standard; the materiality of gold as a type of elemental

prima-materia; the formal composition of the gold bars as a possible corrupted variant of US Minimalist art; gold’s association with elite Swiss bank accounts and hordes of hidden wealth. The work also questioned art’s inextricable enmeshing with a system of monetised value in which it was impossible, and increasingly so in a climate of exacerbated financial speculation and, in the absence of any dependable golden rules, to determine what any artwork was really worth. As historian Tony Judt put it, “We know what things cost but have no idea what they are worth” (

Judt 2010, p. 11). Broodthaers’ deliberately over identifying, hyper-rational half-and-half assignation of value here as though art’s incontrovertible worth could be objectively known was an ironic riposte to capitalism’s increasing deployment of culture as value. Inherently, according to the system of capitalist accumulation, no amount could ever be ‘enough.’ For anything to be really valuable, and given capitalism’s structural demand for infinite expansion, its worth had to continually increase. While one can certainly distinguish a critical attitude behind Broodthaers’ work, it nonetheless remains ambivalent in avoiding targeting the abstract or mythical entity of ‘the market’ as a monolithic enemy per se.

Numerous works of the artists mentioned earlier amplify somewhat, the historical example of Andy Warhol as the world’s first self-proclaimed ‘business artist’. Many contemporary artists of this ilk also exaggerate the primacy of the image of the artist as ‘usable’ currency. Indulging repeatedly in acts of self-revelation and self-showing, they aim to ensure visibility, not only of their art but of themselves. This gesture aims to prove relevancy and demonstrate ‘brand consistency’ (

Steyerl 2017;

Sholette 2010;

Stallabrass 2005). It follows then—as pop star Kanye West recently (and unironically) intuited—that today “artists [...themselves…] are businesses

12”(West in

Young May 2018). Moving from a modernist avant-garde and, even in some cases, postmodern concern for criticality as negativity practiced against the assumptions of the world ‘as it is’, now the ‘entrepreneurialism of the self’ (

Foucault 2011) is fully affirmed and encouraged under the circumstances of a naturalised financialisation. Likewise, every aspect of the artist’s natural life is promoted online as a commodity which has wide ranging implications for contemporary art as a viable critical practice.

3. Beyond Critique: The Biopolitical Self on Social Media

Neoliberalism’s naturalisation of an economic regime transforms all dimensions of contemporary experience: politics, education, health, urbanism, the environment, culture and art. It further transforms self-identity equally dramatically. Corporate culture’s progressive undermining of the powers of the State and governmentality has shifted all onus onto the individual. Foucault saw this shift as announcing the era of the ‘entrepreneurialism of the self’. The biopolitical effects of this tendency have hugely increased over the last 30 years. Biopolitics, the wide-ranging implications of which Foucault had already predicted, makes everyone solely accountable for their actions and choices. In terms of the unrelentingly positivist economic rhetoric by which neoliberalism is purveyed, everyone is now simply free to be a ‘master of their own destiny’. Of course, transferring almost all social and political accountability onto individuals simultaneously presupposes the absence of an effective State capable and willing to intervene for the benefit of a social majority. Naturally, as everyone is redefined as their own ‘freely acting’ enterprise, the demands of constant competition, structurally central to the expansionist aims of financialised capital, swamp every field of human endeavour. The opportunities for endless self-invention touted by neoliberal advocates is in reality a fight for survival. “More generally, neoliberalism has overseen the elevation of individual ambition, competition and self-promotion to cardinal virtues and compulsory survival strategies” (

Haiven 2018, p. 92). From a more ‘negative’ perspective, such a scenario exemplifies the “current bio-economic totalitarianism” of our moment (

Berardi 2012, p. 9).

Under the precarious working conditions established by neoliberalism, entrepreneurialism becomes a naturalised desire. The explosion of the internet and online communicational technologies like social media equally concur with the naturalisation of financialised capitalism. For its neoliberal advocates, the primacy of self-entrepreneurialism represents the very nature of modern life where everyone is a priori an entrepreneur (even if some do not realise it yet). In an acerbically phrased provocation, Silvio Lorusso amplifies this sentiment by ironically applying it to the entire human species. He writes, “Their gaze turns to the past, to the origins of their species; that is when they finally realise […] that they have always been entrepreneurs, except during that historical interlude that goes by the name of civilisation. And this is how will prevails over history” (

Lorrusso 2019: 33). In the absence of either historical consequence or futurity, it is the quasi-Darwinian will of the individual in the present that counts. The entrepreneurial self (and as ‘free agents’ we have almost no choice but to act entrepreneurially to some extent) is a self who is willing themselves into significance. Not surprisingly, “the entrepreneur’s key

medium is personality” (

Lorrusso 2019, p. 27).

For artists on social media, whose platforms in fact “structurally favour the individual” (

Brookchin 2015, p. 155), their entire lives are now ‘willingly’ subject to constant critical presentation and appraisal. Rather than being merely ‘biographical’, artistic identity on social media places increasing emphasis on the ‘whole artist’, the artist’s entire ‘being’ in their ‘natural habitat’. With the division between artist and artwork visibly removed, to criticise the artwork is also to criticise the artist. Accordingly, the individualising dictates of self-entrepreneurialism mean the artist is hypothetically beyond critique because everyone is equally just trying to ‘be themselves’, ‘do their best’ and ‘get ahead’. In view of the inbuilt prerogatives of competition, an artist may outmanoeuvre another or simply be ‘better’, but one cannot criticise the motivation to succeed which is ‘naturally’ the same for everyone.

What this means for art practiced as critique, in opposition to or contradiction of popularly perceived ideas, is undeniably significant. In a scenario where, more generally, “competition is ruthless and solidarity remains the only foreign expression” (

Steyerl 2012, p. 101), the pressure to succeed according to predominant market models, is exacerbated. In fact, critique as a politically dislocating ‘kicking against the pricks’, confronting or upsetting the status quo has been surmounted by the implicit ubiquity to be ‘liked’ and where “interactivity has been reduced to its crudest banality—to ‘like’ something” (

Inventory 2018, p. 14). Historically speaking, this is the precise antithesis of the critical socio-political impulse of art engaged and tactically practiced by key historical avant-gardes (Dada, Surrealism

13, and Constructivism, for example). Despite their ultimate ‘failure’ or co-option (a fact that market apologists never tire of repeating), such collectives sought to antagonise, satirise, undermine, expose or replace a mercantile bourgeoisie who were utterly convinced of their natural entitlement to rule. Reiterating a contemporary type of quasi-feudalism, the idea that the artist’s only role would end defined by their attempting by every possible means to attract the benediction and endorsement of the financial class, would have been unimaginable (

Adamson 2007). Now, heightened competition is instead disguised by an institutionalised emphasis on the ‘positive’ values of politeness and courtesy (

Lorrusso 2019)

14. To be ‘nice’ and ‘liked’ instantaneously in the moment is the reverse of art practiced critically in the spirit of wanting change.

On social media platforms like Instagram, many artists sell an image of themselves that is deliberately curated to greater and lesser extents (

Pallasvuo 2015). It may appear more or less casual, more or less formal and complicit with the pressures of self-entrepreneurialism to varying degrees. Far from the academic deconstruction of presence and identity pursued under postmodernity, a new “longing for presence” and the ‘authentic’ arises (

Widrich 2016, p. 9). Now, it is the artist’s individual self and no longer simply what they make that is primarily offered up to known and unknown audiences. These comprise friends, family and colleagues, but potentially and more importantly influential curators, gallerists and collectors—every artist their own business that is open all the time (

Crary 2013). In a dystopian but nonetheless highly plausible light, it has been suggested that, in the future, the algorithms that determine an individual’s impact and popularity on social media will be deployed more widely to determine basic life prospects, such as employment etc

15. (

The Invisible Committee 2017;

Wright et al. 2016). This is a ‘never say no’ world (

Lauwaert and van Westrenen 2017), a world where every situation is a priori perceived as an opportunity.

Given that the internet is owned by corporations, the artist creatively ‘being themselves’ online is therefore simultaneously enmeshed usually as a small but indispensable player, in the theatre of global business and immaterial ‘content production’. Meanwhile, automated algorithms somehow imitating equally automatic biological processes, glean user-data behind the scenes, calculating collective desires that can continually be put to work financially. The internet and its platforms do not merely facilitate the presentation of creative individualities; they also shape them. Oddly, this incitement to individuality concurs with an online situation in which there is no longer any privacy (

Zuboff 2019). The ambience of autonomy which the fluidity of social media affectively encourages, at the same time, allows for greater penetration of users’ real habits and desires. The “constant bombardment of signs of success online” (

Lorrusso 2019, p. 46) provokes persistent enthusiastic interaction. Like other contemporary forms of work, particularly managerialism, in which the individual is entrepreneurially called to the fore, it is frequently undertaken in a spirit of “cheerfulness [that] can only be maintained if one has a near-total absence of any critical reflexivity” (

Fisher 2009, p. 54). Meanwhile, the self-entrepreneur becomes a type of self-optimising entity, a “Needy Opportunist” (

The Invisible Committee 2017, p. 100).

The predominance and accessibility of social media has meant that certain artists have contextually addressed it in a meta-critical way. Many of these practices have been lumped together under the rather amorphous term ‘Post-Internet Art’, which loosely refers to a range of art practices that cite, appropriate or refer to internet languages, imagery and behaviours. Amalia Ulman, for example, began by targeting Instagram as the contextual site of a series of ‘identity-fictions’ (

Ulman 2018), which were crafted according to a number of online representational clichés of femininity. At one point, she was an inner-city bohemian; the next a fitness enthusiast; a clean-living, upper-middle class entrepreneur; a young mother to be; a bored, immaculately attired trust-fund kid; a hospital patient; a winsome self-styled Lolita; an international fashion model; or a globe-trotting socialite. Often interspersed among these disparate self-stylings are utterly banal appropriated quotes of the predictably ‘inspirational’ kind endemic to social media. Self-consciously styled, collectively indifferent references to pressing global issues like poverty or ‘world hunger’ are also invoked in direct proximity to other social media staples like food posts, travel photos and selfies. Fully at home in social media as a creative medium, the potential criticality of such work resides in its self-knowingness and its ultimate framing of social media as eminently enclosed rather than openly expressive, bounded by series upon series of repeatedly predictable tropes: the Self social media fashions particularly for young women because social media actively constructs rather than merely represents identities, and is one incited by the aspirational reproduction of uniformly recognisable (life)styles (

Connor et al. 2019). Still, this work, while eschewing social media blandness and conformity, could not be claimed as necessarily critical. Besides, opposition becomes impossible when the media environment is enveloping and inescapable and the values it endorses are held to be ‘only natural’. The relocation of Ulman’s work to a museum exhibition context however seems to undermine its para-subversive effect within Instagram, where it acts parasitically. Tellingly, Ulman never presents herself as ‘an artist’ online but as just ‘a person’, making it initially at least, virtually impossible to gauge who she ‘really is’. Conversely, the work of a postmodern artist like Cindy Sherman, as far as such work classically relies on critical distanciation, interrogates identity and feminine identity as (con)textual construction, a synthetic artifice. Sherman’s recent embrace of Instagram repeats in a different, though intimately related idiom, the lessons of her earlier work. Ulman’s work alternatively naturalises an artifice that has been wholly internalised as ‘real’.

The Australian artist Giselle Stanborough similarly engages Instagram as a primary locus of her practice. Aesthetically, Stanborough’s work often parodies populist and kitsch aspects of social media. It particularly targets those common genres that place the author at their centre as some kind of ‘knowledge expert’ accompanied by positive and ‘inspirational’ statements that are actually clichéd and bathetic. Much of the artist’s work on Instagram includes captions and theoretical explanations relating to the exploitative aspects of social media and the internet that transforms the Self into human capital. In one, she bemoans the fact that an image of herself, photographed in connection with a major exhibition, legally belongs to the commercial digital archive Shutterstock; “On IG you can exchange your self image for some social capital whilst Zuckerballs makes the economic capital, but you’ll never know what your own eyeballs are actually worth

16” (

Stanborough 2020). Despite this ‘critical’ knowingness and the reiteration of post-Marxist terms like ‘semiocapital’, Stansborough repeatedly relies on foregrounding her appearance to propel her work. In critiquing the capitalist biopolitics of social media, professionally the image of the artist cannot, at least through her work,

not be known. Critical negativity is undermined by an apparently permanent commitment to visibility and self-exposure, emphases that affirm everything the artist seems to be criticising. Unless, of course, there is no alternative.

The work of video artist Ryan Trecartin is also saturated with the languages of social media. It especially mimics the types of YouTube lifestyle countercultures that attract almost fanatically devoted subscribers. These usually feature users venting personal misgivings or conversely, celebrating their difference often via fetishistic recourse to commercial merchandise (without being official brand endorsements). Trecartin hires actors to portray contemporary pop-cultural stereotypes, particularly those associated with Los Angeles. Like many self-presentations on social media, Trecartin’s work vacillates between formalism and casualness, between tight scripting and seeming improvisation. The characters in many of Trecartin’s videos like “I-BE AREA in Out of Order YouTube messy-format” (2008) and “CoreaINC.K (section a)” (2009) adopt the poses of wannabe brats of the sort renowned for gravitating towards showbiz epicentres like Los Angeles. The styling of these characters draws out the underlying abjection of a system of self-exposure that depends structurally on an individual’s capacity for self-humiliation as a means to get ‘what they want’ (

Haiven 2018). Desire here is the desire for visibility for its own sake: characters whine and complain, compete and bitch among themselves in the most mannered and exaggerated fashion. They indulge in acts of conspicuous consumption and appear entirely obsessed with conforming to particular media representations of a ‘wild’ unleashed (albeit borderline) stardom of endless parties punctuated by inescapable service work. The more vapid but outrageous a character, the more obvious their attempt to foreground themselves at the expense of their competitors, who happen also to be their ‘friends’. Trecartin’s absorption of social media and B-grade would-be-celebrity cultures transforms them into phantasmagoria that are both nightmarishly ‘psychotic’ and absurdly humorous. It represents something like an inherited inversion of the consumerist 1980s where “bigger, more, faster, wilder, crazier” (

Lauwaert and van Westrenen 2017, p. 20) meant everything. But like Ulman’s work, it is difficult to accept such work automatically as critical. It is somehow too entertaining for that. With seemingly nothing beyond the system of financialisation (

Harvey 2019;

Haiven 2018), everyone is caught up in a fluid whirlpool of entrepreneurially forced interaction and self-exposure. The queered dimension of Trecartin’s work (

Connor et al. 2019)—i.e., the fact that many performing in his videos are either transgender or in drag—adds to its ambience of destabilised fluidity. Everyone attempts furtively to distinguish themselves from within a frenetic though cyclically repetitious and aimless morass. Failure to do so would mean drowning in indistinguishability, of being no-one.

The internet and social media as a naturalised ‘habitat’ for artists, controlled by corporations and inciting individual competition to a Darwinian degree, aligns with and reinforces the naturalisation of financialised capital. In that system, rather than a freely acting critical agent, the user, the artist, is purveyed as a Self for sale.

4. Revenge of the Biosphere: Collapsing Neoliberal Naturalism and Self-Annulling Critique

The contemporary artist’s self-exploitation coincides with neoliberalism’s implicit incitement to constantly self-entrepreneurialise. Artists have long been known for their entrepreneurial prowess, a skill partially engendered by the traditional precarity of artistic life. Corresponding constructions of artistic identity see creative productivity as the natural outcome of a scenario where there is ‘no one but yourself’ to rely on. The motivation to self-entrepreneurialism extends the principles of ‘creative’ self-promotion normally associated with artistic activity, to society in general. As with the naturalisation of neoliberal economics, the self ‘out-for-itself’ is the natural actor within this scenario. This is homo-economicus, the individual as ‘enterprise-unit’ whose entire being is conditioned competitively by economic, goal-orientated drives (

Foucault 2011). However, the decades-long success of neoliberalism and its almost total economisation of life is currently facing an extreme challenge. A prelude was glimpsed in the 2007–2008 global financial crash triggered by the corporate collapse of the US housing market which, in turn, was precipitated precisely by the type of high-risk financial speculation that neoliberalism intrinsically encourages (

Mann 2019). It should have been viewed as a warning of financialised capitalism’s limits and dangers. Instead, those corporations responsible were (cynically and rather unbelievably) bailed out via US treasury aid. Whilst pedalling neoclassical numeric models that supposedly favour organic market (and, therefore, social) equilibrium, neoliberalism as a fragmented though totalising economic ideology, is shot through with massive irreconcilable contradictions (as is capitalism in general):

“Every reason which they (the economists) put forward against crisis is an exorcised contradiction, and therefore a real contradiction. The desire to convince oneself of the non-existence of contradictions, is at the same time the expression of a pious wish that the contradictions, which are really present, should not exist”.

Wishing away contradictions that expose the extremely synthetic, ad-hoc improvisational abstraction of contemporary capitalist thinking (

Harvey 2019) can only go so far. The pretence of natural economics is presently laid bare when faced with the seemingly unstoppable force of a biological agent that is very specifically real: the COVID-19 virus. Apart from its virulent morbidity, COVID-19 has already wreaked havoc on financialised economies worldwide (

Tooze 2020). An economic system that was often portrayed to be as cyclically natural as the weather has revealed itself instead as especially improvisational, weak and vulnerable. The massive curtailing and/or temporary cessation of relentless capitalist activity as the result of the worldwide lockdowns of communities, has effectively strangled a neoliberal system whose primary purpose is to keep itself ‘alive’ and continually expanding (

Latour 2018;

Jappe 2017;

Bang Larsen 2011) (ironically not unlike the virus). As the impact of this crisis becomes increasingly evident the longer economic flows are stifled, it is clear that financialisation feeds on populaces and discards them when they are no longer useful. The glaring socioeconomic inequalities provoked and grossly intensified by neoliberal practices (the 1% of global wealthy elites violently opposing 99% of ‘others’, to paraphrase Occupy Wall Street sloganeering) (

Graeber 2014) are even further magnified by the current crisis. There is nothing ‘natural’ about this and those who suffer most as a result of exacerbated economic hardship deserve less to than those who, because of their inherited privileges, have had privileged access to the necessary financial tools to ensure their dominance and self-insulation (

Bridle 2018).

Meanwhile, a rising tide of dissent in the form of mass protests, as well other forms of cultural criticism (

McKee 2019), has been activated by multiplying awareness of the sheer extent of structural exploitation occasioned by neoliberal financialisation. At the same time, it was as if the indifference of the biological order indicated by the spread of the COVID-19 virus, and by the escalating, clearly observable effects of global climate change, was the true critic in this scenario—a critic entirely devoid of subjective agency. Current economic and social fallout provoked by the effects of COVID-19 as it progressively shreds the dominance of the neoliberal system of financialised capitalism indicates the possible crest of an unravelling that has been a long time coming. The further attenuated and abstracted the economic system becomes, the more open it is to rife inconsistencies, failure and collapse, and/or the reawakening of barbarised essentialisms in the guise of globally emergent fascisms (

Žižek 2019;

Lindt and What/How & for Whom 2014).

Leading to this situation, the contemporary art world has incrementally absorbed and celebrated neoliberal ideology and practices knowingly and unknowingly. It has clearly not been progressively resistant and critically committed as a whole. Since the dawning of neoliberalism, the global art world has transformed itself accordingly. As a result, “Contemporary art thus not only reflects, but actively intervenes in the transition toward a new post-Cold War world order. It is a major player in unevenly advancing semiocapitalism” (

Steyerl 2012, p. 94). Contemporary art’s increasing dalliance with financialised capitalism means that it “faces a potentially terminal crisis. Contemporary art has sold itself as a non-specific, expanding, universal non-genre, much as neoliberalism passed itself off as the natural state of things”. Furthermore, what does it mean to deploy art as a means of critique when “radical art is nowadays very often sponsored by the most predatory banks or arms traders and is completely embedded in the rhetoric of city marketing, branding and social engineering” (

Steyerl 2012). Is there any means by which contemporary art as a legitimate form of critical, oppositional or resistant practice is not always already institutionally rendered merely representational? (

Boltanski and Chiapello 2018). When the dominant institutions that publicly denote ‘contemporary art’—e.g., museums, commercial galleries, biennales—are already ensconced within a system that exploits labour and resources, is there any means by which critical content can appear as anything but compensatory ‘virtue signalling’? Certainly, there is no dearth of ‘critical’ content in contemporary art. Any number of ethically challenging and/or disturbing socio-political subjects have been presented within the major networks by which contemporary art is most recognisable. Biennales in particular are highly known to exhibit diverse varieties of contemporary art that globally address precisely such content. Nonetheless, the critical content of art exhibited in biennales does not guarantee its critical efficacy. Mass international art events like biennales collectively and paradoxically, represent a “true capitalist venture that as a rule is sustained by an ‘anti-capitalist’ ideology…” (

Žižek 2015, p. 174). Similarly, “A biennial can offer a platform for uttering critical slogans, precisely because the organisational grammar of global circulation neutralises their meaning” (

Szreder 2017, p. 5). Is any critical gesture in art rendered impotent from the start when every desire to alter the status quo is a priori enclosed by it?

Because art itself is an institution, the mere denomination ‘art’ already sets it aside as its own institutional category regardless of where it is appears (

Fraser 2006). Any critical gesture must take this into account. Rather than pursuing the types of acutely targeted criticism enacted by well-known key figures of the ‘first wave’ of institutional critique like Hans Haacke, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Jenny Holzer or Barbara Kruger (

Alberro and Blake 2009), there are many revivified manifestations of critical art today that address art’s institutionalisation and deploy quite different tactics. The critical tendencies embodied by these might collectively be described as ‘self-annulling’ (

Agamben 1999). In such work, art addresses its institutional contexts while simultaneously questioning the artist’s own complicity in the networks of its institutional embedding. Such work does not foreground the artist as author, the ‘inventor’ of a ‘solution’ to the critical situations addressed. Instead, it instigates an implosive closed circuit in which the artist, artwork, institutional context and audience are all inextricably bound. Fittingly, such art tends to undermine the commodity-fetish character of art because without the context addressed, there is no artwork. These sorts of heterogenous critical gestures do not side with a Hegelian dialectic that pre-empts resolution though overcoming; they do not pretend to be able to ‘fix’ the phenomena they critically identify by exposing it. Neither is the identity of such art exaggeratedly complex as series of semiotically encoded ‘texts’, as in much postmodern critical art. In fact, such work is more properly aligned with the spirit of Adorno’s negative dialectics in that it openly thinks through the circumstances of its own construction/deconstruction at the moment of its ‘exhibition’. It is collectively antithetical to the positivity expected of art as a product of self-entrepreneurial calculation (even if it might parody this at times). It is a response to a wider phenomenon that does away “with the remainders of cultural production as dissent, as controversy and as the creation of public spheres; to promote creative industries as pure and affirmative function of economy and state apparatus” (

Raunig 2013, p. 113).

Self-annulling art is stubbornly obstructive (sometimes physically), refusing to side either with institutional prioritisation or the equally institutionalised myth of individual artistic agency. Not surprisingly, critique of this nature emerges from a wider crisis situation occasioned by the transformation of all potential into economic utility. This occurs despite the growing evidence of the structurally implosive conditions of financialised reasoning that ultimately threatens life itself. Such critique, whether as urban art/activism, networked intervention or parasitical services, emphasises the unnaturalness of a bio-politicised economic ideology that persists in projecting blanket financial incentivisation as natural.

Contextual deployments of ‘self-annulling’ critique extend to urbanism and are increasingly evident in contemporary traversals of art and activism. Between 2003 and 2007 a loose creative collective that included artists (but was not wholly comprised of them) called

L’Isola dell’Arte (roughly translating as ‘the Island of Art’) occupied a large industrial space in Milan called the ‘Stecca’ (or ‘Stecca degli Artigiani’).

L’Isola dell’Arte represented an independent agglomeration of differentiated though intersecting interests and activities. Within the Stecca, specialisation coincided with free and experimental exchanges among occupants with considerably different interests and expertise. Under the pressures of neoliberalism, the provisional and socialised autonomy of this arrangement met serious challenges. Rapidly accelerated gentrification is a key expression of neoliberalism in action (

McKee 2019) and glaringly obvious to anyone who has lived in an urban centre during the past 20 years. In Milan, its impinging effects meant that the land on which the Stecca stood was eventually bought by an international real estate conglomerate

Hines and the

Ligresti Group (

Raunig 2013). The profit motives of this corporate alliance (and almost all like them) promoted an urban renaissance for the soon to be ex-industrial areas of the city that “intended to attract the newly rich creative class” (

Raunig 2013, p. 132).

At the same time, real estate interests supported by right-wing government, demonised the ‘illegal’ and non-conformist activities of the building’s industrious long-term residents who had staged their own non-institutionally validated creative ‘renaissance’ years earlier. Before eviction, the members of

L’Isola dell’Arte staged a project composed of a series “fight-specific” (

Raunig 2013, p. 136) (as opposed to site-specific) art works scattered throughout the Stecca’s spaces (

Gawronski 2020). These works collectively formed a totalising environment, a type of

gesamtkunstwerk that ironically alluded to the immersive Environments and Happenings of the 1960s and 1970s. At the same time, the inbuilt militancy of the exhibited art served to intentionally obstruct and render as difficult as possible the demolition of the Stecca and the eviction of its residents (

Raunig 2013) (

Figure 2). Like a series of unfolding, interconnecting barricades, the project implied its inevitable destruction as the productive purpose of art’s work more generally. The negation of art served as a defiant gesture and constituted the true art of this collective endeavour. Rather than simply functionalised as a ‘tool for protest’, the destruction of art here threw into relief its problematic contextual siting within an economised environment that will only validate art according to its own self-aggrandising terms.

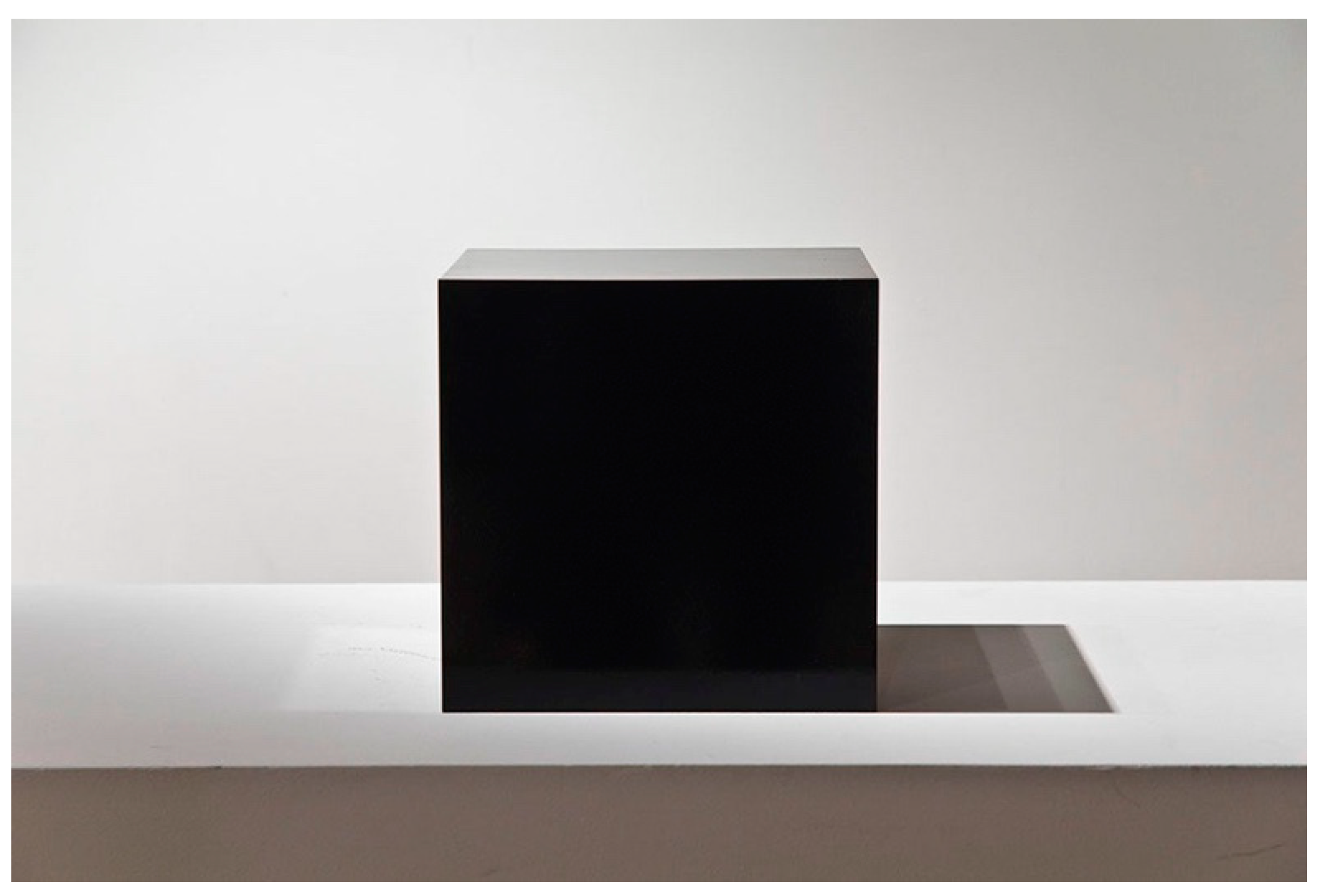

The problematising of the critical function of art beyond the limits of its traditional definitions as encompassed by the

L’Isola dell’ Arte project above finds many counterparts elsewhere. A growing number of these specifically target the networks of financialised capital. The internet’s ubiquity in advanced capitalist societies and an awareness of the sheer extent of its networked and circulatory spaces has simultaneously made the internet a key locus of art-critical activity of an entirely different order than those previously analysed historically. American artist Caleb Larsen’s “A Tool to Deceive and Slaughter” (2007–2012), which appeared as a featureless black cube that is plugged into a computer (

Figure 3), represents a telling example. The cube perpetually sold itself algorithmically on eBay and checked whether it had been purchased every 10 minutes. As part of the ‘purchaser agreement’ scripted by the artist, once the object was sold the current owner had to ship the cube to its new owner who would agree to immediately reconnect it to the internet, thus reactivating the object’s self-auctioning function on eBay (

Scott 2010). The object was deemed ‘art’ by the artist only when it was connected to the internet (

Larsen 2009). The cube was structurally destined for perpetual circulation. Unable to be owned in perpetuity as an artwork, neither could it be properly collected or appreciated as an accumulated commodity. The emphasis on circulation triggered by the object’s purchase highlighted the predominant function of financialised capital as ‘value in motion.’ Value begets value without the necessary intervention of an object as commodity (

Harvey 2019). The concept behind “A Tool to Deceive and Slaughter” undid the typical notion of the artwork as commodity; as an artwork it eternally frustrated this possibility via constant self-negation.

In 2014, Catalan artist Núria Güell teamed with the Cuban artist Levi Orta to produce the work “The Generated Political Act”, for which they established their own offshore tax haven. This ‘artwork’ arose from a backdrop of local and international scandals involving high-ranking politicians and multinational corporations embezzling funds and transferring them invisibly to precisely such havens. Related actions were perhaps most famously exposed in the publication of the scandalous contents of the so-called Panama Papers. The Panama Papers comprised millions of leaked documents that exposed personal financial information of ultra-wealthy individuals, many of whom were engaged in fraud, tax evasion and evading international law via recourse to offshore shell companies (

Murphy 2017). After theorising the work, Güell and Orta approached the well-known business school

ESADE for advice on how to essentially exploit legal loopholes to realise their ‘concept’. Once established and legally ratified, the artists proceeded to offer anti-capitalist Catalan activists’ free access to the tax haven. As a result, these activists were able to transfer funds intended for social causes anonymously and with legal impunity. At the same time, they successfully elided at least on a domestic scale, the draconian austerity measures imposed by the Spanish state (representing one of Europe’s alleged economic ‘basket cases’ like Greece, Italy and Ireland) and typically impacting all social services (

Haiven 2018). On the strength of this work, the artists were invited to exhibit at the prestigious Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid. Here, they extended the work through an additional gesture they referred to as an ‘Ethical Protocol’ (

Nieuwenhof 2015). This enabled the secondary transfer of additional funds from the realm of neoliberal high finance to oppositional anti-capitalist agitators outside it. In this way, the art world, in the figure of an internationally renowned public institution, was redeployed for genuine agitational purposes in collaboration with the artists they invited. More broadly, the project was a means to discuss how “the tools of financial circulation could be appropriated to undermine or challenge the system” (

Haiven 2018, p. 105) while recognising both the widespread corruption and severe limitations of governmental politics under neoliberal conditions. As art, it produced nothing concrete (although a certificate of authentication exists) but incited instead social/political/cultural effects. At the same time, the potential real-world impact of these remain ultimately unfixed and unknowable: the artwork does not replace art with a social service as a wholly positivist gesture but sets in motion possibilities that render the ‘artwork’ primarily a circulatory conduit.

Such enabling extends to other examples that critically target the identity of the artist assumed to be a public ‘service provider’. With more pressure for artists to ‘perform them-selves’ alongside the exponential growth under neoliberalism of a welter of specialised service cultures (

Bishop 2012), certain artists have engaged such tendencies parasitically. In 2006, Sydney-based artist Sarah Goffman appeared at a local independent gallery Loose Projects, behind her own crudely constructed booth offering ‘Psychiatric Help’ (

Figure 4). The artist, with no training in psychiatry, deliberately appeared as a cartoonish avatar of that discipline. In fact, Goffman’s was a real-world rendering of the same booth famously attended by the character ‘Lucy’ in Charles Schultz’s comic strip

Peanuts populated by young children voicing the existential concerns of adults. In the cartoon, the characteristically prickly but resourceful Lucy utilises her homemade cardboard psychiatrist’s booth primarily as a means of assuming power by drawing attention to herself while feigning knowledge she does not possess. Goffman’s blatant and humorous imposture seemed to parody the ethical pretensions of ‘relational art’ (while hinting at clichés of the mental instability of the artist, the supposed hairline separation of genius from insanity). Made famous and widely popularised in the contemporary art world after Nicholas Bourriaud’s 1988 book,

Relational Aesthetics, much associated art emphasises commonplace non-art activities reframed in institutional contexts. While potentially critically de-emphasising art’s traditional commodity identity, relational art almost uniformly connotes a positive outlook, a fundamental social orientation that has quasi-educational if not therapeutic intentions. At the same time, relational art emerges at exactly that moment that neoliberalism’s ruthless stripping of social services seems most accomplished; the arena of contemporary art becomes a type of crude, neutered proxy for those same services (

Bishop 2012). The artist, unable to offer anything of ‘real’ value themselves, is convinced they must (or is forced to) perform other roles which may seem related but for which they are totally unqualified. In a related vein, Mark Fisher identifies that “what late capitalism repeats from Stalinism is just this valuing of symbols of achievement over actual achievement” (

Fisher 2009, p. 43).

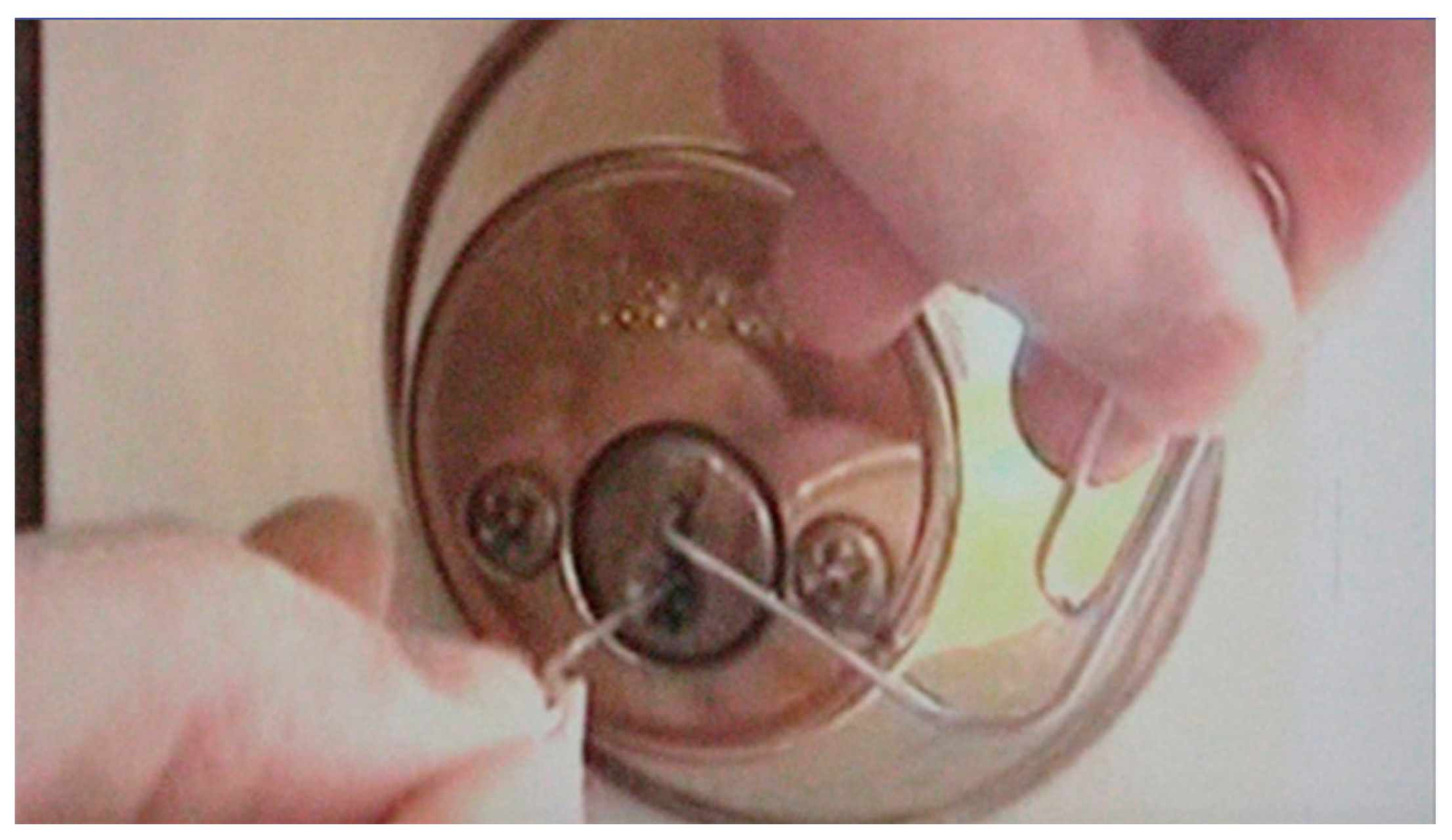

As we have seen, the contemporary world is heavily impacted by the naturalised imperative for practitioners to view art as self-selling mostly via the accessibility of the internet. However, beyond the smooth terrain of online interaction, access to the workings of much institutional activity remains resolutely closed. Such activity is invisible, inaccessible and deliberately occluded. What goes on behind closed doors in the banking and finance worlds for instance? How do big brand-name contemporary art institutions attract funding, and how and in what fields do their principal donors make their money? What is clear in both instances is that not everything is as above-board as we are typically led to believe. For example, the Panama Papers, as mentioned earlier, politically revealed almost unimaginable levels of individual and corporate wrongdoing while a number of highly-visible contemporary art galleries and institutions have been embroiled in surprisingly unethical activities

17 (

Warsza 2017;

Steyerl 2017;

Holert 2013). Collectively, we are locked out of direct access to an awareness of the sorts of decisions that determine how society’s dominant institutions function and are supported. Recognition of this widespread structural prohibition is echoed in the 2006 video work,

Instructions for the Sharing of Private Property by Claire Fontaine (the artistic

nom de plume of the duo Fulvia Carnevale and James Thornhill). The work is a matter-of fact, ostensibly artless video that appears as retrieved footage presenting detailed demonstrations of how anyone can make an array of lock-picking devices from readily available tools and objects. The work offers a type of service while ‘expressing’ nothing and nothing of the fictional artist’s ‘personality’. It invents nothing either. What it implies, however, is deeply inventive and resourceful: how to go where you are forbidden. The work ‘shows’ without commentary. It offers potentially usable ‘information’ that is neither strictly legal nor illegal. It does not explicitly cajole, encourage or discourage the audience one way or the other. The work’s inexpressive anti-aesthetic blankness and presentational ambivalence effectively disappears it as ‘art’. Its real artfulness arises in the socio-political ramifications of the parasitical service it appears to offer. Today, we are constantly urged to participate and yet we are debarred absolutely from participation in many areas of global life that fundamentally shape its experience. When incidences of wage and corporate theft are well documented and much global politics is exposed as the interaction of secretive cadres of corrupt elites, we might be reminded of Berthold Brecht’s famous quip, ‘what is the robbing of a bank compared to the founding of a bank’ (

Brecht 1928). In Fontaine’s work, the suggestion of ‘un-doing’, of subtracting rather than positing, expropriating rather than contributing (

Foster 2020), constitutes its actual contribution.

Lastly, we must return to the unavoidable centrality of the current impact of biological and ecological worlds, the uses and abuses of which fuel the continuation of a deeply fraught capitalist system. Nature has been referenced within a contemporary art context in ways that are deeply critical rather than placatingly affirmative of its ‘timeless beauty’. In 2018, the Critical Art Ensemble (CAE), who have a long history of research-attuned activist art, exhibited “Environmental Triage: An Experiment in Democracy and Necropolitics”, as part of the ecologically themed exhibition ‘The God Trick’ at PAV (Parco Arte Vivante), Turin’s experimental centre for Living Arts (

Figure 5). The work deployed the medical concept of triage, which determines, in an emergency, which patients should be treated first, or if at all, according to the seriousness of their injuries. In this case, the CAE undertook ecological research into the waterways around the large industrial city of Turin in Italy. Over the course of this research, they identified multiple degrees of contamination in each targeted water source. Within the institutional context of PAV, maps were displayed that geographically located the examined bodies of water and listed the number and extent of pollutants in each. Water from every water source analysed was displayed in glass cubes, arranged like minimalist sculptures and formally echoing Hans Haacke’s famous “Condensation Cube” of 1965. The work was politically more aligned with that artist’s 1970 “MoMA Poll” at the Museum of Modern Art New York where Haacke installed two similar transparent cubes acting as audience ballot boxes addressed to the question ‘Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November?’ The CAE specifically refers to the piece as one of the “greatest necropolitical artworks

18” (

Critical Art Ensemble 2018). As Haacke was famous for posing controversial audience surveys that often exposed the less-than-pure machinations of the major institutions that exhibited his work, so in this case the CAE asked audiences—and in lieu of the practice of

triage—to vote for which waterway/s they believed was/were ‘worthy’ of saving. The ‘value’ of the artwork, as far as contemporary art is routinely pressured to reinforce luxury commodity logic, is deflected here to approximate the relative value of the ‘real world’. Considering the undeniable extent of human climate impact, nature, by no means a simple thing, can no longer be feasibly theorised-away as primarily a cultural abstraction (

Malm 2020). In an art context, the work functioned, like much of the CAE’s work, to critically undermine the economic relativisation of value in an art context: the value is not ‘in’ the work but crucially elsewhere in a much larger arena, the natural world, that could ultimately spell the annulling of all art and all life.

5. Conclusions: Contemporary Art as Critical ‘Un-Doing’

“Today, it is the relations constituting the space of global capitalist modernity, overdetermining other social relations with an insistent yet disjunctive and crisis-ridden contemporaneity, that must first be understood, as a condition of the renewal of criticism that is to be at once both historical and emphatic (related to truth), and hence

negative in relation to the world as it is19”.

LET US PREPARE WORDS AND IMAGES THAT DO NOT SATISFY BUT IRRITATE.

Self-annulling critique deploys criticism in art as an implosive principle. It signals to undermine the sanctity of art-as-commodity even if that fetish is still believed to contain critical capabilities.

20 As a contemporary tendency, it speaks to a greater scenario in which critical negativity and its expressions are routinely discouraged if not projected as impossible (

Graw 2018;

Avanessian 2013). Broadly speaking, “critical aversion to negativity is symptomatic of the dominant cultural dynamics that systematically stop us from cultivating language and other tools for speaking through our alienations” (

Thaemlitz 2015, p. 218). However, the negative impacts of a naturalised system of financialised capital continue to mount. Alienations multiply in face of the economic fallout of COVID-19 and the increasingly un-ignorable effects of climate change. Such macroscopic challenges notwithstanding, the concurrent imperative that every individual act as a self-entrepreneur impacts on artists who are traditionally regarded as doyens of individualism self-motivated by passion. It is no accident that post-Fordist labour constituting the so-called ‘knowledge industry’ has appropriated so many cues from the example of artists and other creative practitioners. Endlessly implored to continually market ourselves as artists and as ‘intellectual labourers’, perhaps the most incisively critical function of art and the artist today is active withdrawal (

Ciric 2016).

In 1977, Croatian conceptual artist Mladen Stilinović published a series of black and white photographs of himself lying on a couch asleep or half-asleep, just ‘lounging around’. Stilinović famously captioned the series, “Artist at Work”. In a spirit of continuity, he published a text in 2011 called In Praise of Laziness. Today, ‘not-doing’ is potentially the most disruptive critical gesture available to art. This is especially the case when the artist is believed to be ‘inspired’ at all times, their popularly portrayed embodiment thereby conveniently contributing a central myth to the entrepreneurialism of the self that seeks to recoup all unused capital potential. Hypothetically speaking, the tactical withdrawal of artists from the institutionalised spaces of the contemporary art world might function something like a General Strike, forcing increasingly corporatised institutions to rethink their social and political purpose.

‘Un-doing’ as a form of critical intervention has a long history, hinted at in examples already considered here, and not one necessarily marked by the luxury of mere idleness. Many venerated practitioners have ‘retired’ from art not wholly as a simple act of ‘quitting’ but as a strategic withdrawal from a system they believed to be hopelessly compromised by the financialised conditions determining art’s institutional presentation, a challenge to the system itself. One notable example is Cady Noland, whose work is a poetic but undeniably acerbic and affective rejoinder to the socio-political paradoxes of contemporary America as the supposed land of the free on the one hand, and terrain of seemingly interminable racism, brutality and exploitation on the other—a condition arguably greatly amplified at present. As a globally networked market system, the neoliberal art world adores mystery as much as material scarcity. It valorises the former for what it confirms of traditionalist notions of artistic exceptionality and the latter as luxury commodity fetishism. It is not surprising then that Noland’s critical reputation only increased after her highly visible departure from it. In view of this, the artist cited generally how “artists ‘get screwed’ by their dealers” (

Noland in Herbert 2016, p. 103) and other art world professionals, and specifically an instance of censorship by a gallerist concerned that her art would offend collectors. In fact, the artist only resurfaced more recently to legally contest the exhibition of her works, parts of which had been reconstructed without her permission, by order of the institutions that exhibited them (

Herbert 2016).

Critical tactics of withdrawal and refusal afford opportunities to think through the real crises of our times. To withdraw is to deliberately stop and take stock of a situation and is therefore, once again, an active proposition. Rebutting the contextual terrain of a contemporary progressive politics also marked by the imperative to constantly ‘participate’, Žižek counters saying, “to refuse to participate—this is the necessary first step that as it were clears the ground for true activity, for an act that will effectively change the coordinates of the constellation” (

Žižek 2017, p. 277). It is a frustration of the instantaneity of dominant (social) media paradigms that demand the artist to always be present. It is a tactic both understandable and resistant to a scenario in which no matter how hard one works, the productive and appropriative circumstances of the prevailing system grants visibility (and its attendant privileges) to only a very few. In terms of percentages, a diminutive number of artists globally attain the apex of the art market pyramid even if they want to; the rest remain ‘dark matter’, perpetually toiling in its shadow while constantly contributing surplus value (

Sholette 2010).

While not wholly bound, art is nonetheless unquestionably historically bound to capitalism (

Haiven 2018). Today, this entwining seems total. For art to function critically today it must, in whatever way, recognise and critique as a matter of necessity, naturalised capitalism’s contemporary operations and widespread negative impacts both inside and outside the artworld. These have effectively put everything and everyone to use. The virulent, unlocatable, ‘immaterial’ yet materially destructive flows of global finance as pure value appear to signal, from a historical perspective, the culmination of a particular world trajectory in which these forms can go no further without destroying everything (

Latour 2018;

Jappe 2017). The financialisation of the economy, set in motion by neoliberalism, thrives principally for the sake of the system of circulation

itself and clearly not for the good of society. The latter, in any case, was deemed to no longer exist, at least since 1987, when one of neoliberalism’s foremost proponents, Margaret Thatcher, infamously stated, matter-of-factly, ‘You know, there is no such thing as a society’. Yet what if “the greatest threat to the status quo, at least in the liberal West, is simply a lack of enthusiasm and activity? What if rather than inciting violence or explicit refusal, contemporary capitalism is simply met with a yawn?” (

Davies 2016, p. 134). The statement incidentally recalls graffiti scrawled on the wall of a bank during the 2001 Carnival Against Capital in Québec, ‘Capitalism is Boring’ (

Notes from Nowhere 2013, p. 179). The critical potential of refusal is only heightened when the “exigencies of the market both favour young artists and guarantee that the political content of their work will in no way present a threat to neoliberalism as an economic system” (

Watson 2019, p. 42).

In order to embrace its lingering critical capabilities, contemporary art that considers critique still viable under conditions of its endemic financialisation must take this context, or related contexts, into account without necessarily having to spell them out. Doing so simply coincides with the prevalence of critique in art as illustration: just as money is the primary representation of capital (

Haiven 2018), so depicting critical ‘content’ in art merely

portrays a heterogenous variety of dissenting positions. To address the negative effects of contemporary capitalism as crucial to the pursuit of art

as critique is not to automatically claim art exists

outside capital but to recognise that it

could and has: “Every act of making art stays in a tradition that is not totally defined by the art market… Art was made before the emergence of capitalism and the art market, and will be made after they disappear” (

Groys 2010, p. 18).

Not surprisingly, there is currently a “growing contingent of market-averse artists” (

Pasero 2013, p. 160). For some, “art-praxis has become crucial to a language of exit from, and negation of, capital” (

Roberts 2013, p. 70). This critical inclination was presaged much earlier. For example, in 1969, US artist Lee Lozano announced she was staging an ‘art strike’, in her “General Strike Piece”. She would not make or view art, or visit any openings, or attend any events connected with art or the art world and would also give up all personal habits associated with these (

Haiven 2018). Today, such disavowal speaks of broader alienation but also projects art as a critical ‘un-doing’ that undermines its popular perception as inherently positivist. Lozano performed a type of negative artwork, the productivist identity of the artist and artwork ‘unnaturally’ turned inside out (

Applin 2018). More recently, Claire Fontaine (