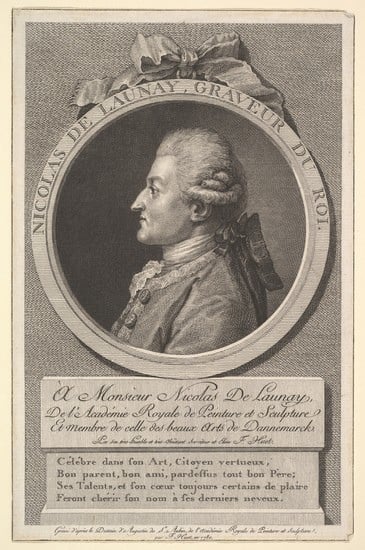

Cutting Edges: Professional Hierarchy vs. Creative Identity in Nicolas de Launay’s Fine Art Prints

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Très Humble et très Obéissant Serviteur

2. The Double Seduction: Framing Decoration and the Print Business

M. Delaunay, Engraver to the King, of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, has just published a new print after M. Fragonard, Painter to the King and of the same Academy; its title is Les Beignets, and is worthy of the talents of the two Artists; it follows on those which appeared some time ago […]; and will complete the six Precious Prints of this genre, which M. Delaunay intends to publish.5

[T]he true art lovers look for merit in paintings, and do not hesitate to acquire a precious picture that has no pendant: but those who are only concerned with decoration are not very interested in the merit of the works, & much on their correspondence […]. Today, prints are hardly bought except as furniture; an engraver cannot promise himself a sale of a print if he does not accompany it with a corresponding print. As soon as he has engraved a plate, he must hurry to engrave the pendant.7

3. “Every Man under His Vine and Fig Tree”: The Clientele, the Real and the Ideal

“occupied with the governing of her family, she rules over her husband through kindness, over her children through sweetness […] her house is the abode of religious sentiment, filial piety, […] order, interior peace, gentle sleep and of health: thrifty and settled, she thereby avoids passions and needs; the poor man who comes to her door is never turned away.”19

4. The Nature of the “True Artist”

5. To Touch with One’s Eyes: Visual Illusion and Sensory Experience

6. Inside Out

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A Short History of Trade Cards. 1931. Bulletin of the Business Historical Society 5: 1–6.

- Adanson, Michel. 1763. Familles des Plantes. Paris: Vincent, pp. 380–81. [Google Scholar]

- Addison, Joseph. 1712. Pleasures of Imagination. The Spectator, 411–21. [Google Scholar]

- Auslander, Leora. 1996. Taste and Power: Furnishing Modern France. Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bellhouse, Mary L. 1991. Visual Myths of Female Identity in Eighteenth-Century France. International Political Science Review/Revue Internationale De Science Politique 12: 117–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1969. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, (1935). In Illuminations. Edited by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken Books, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Maxine. 2002. From Imitation to Invention: Creating Commodities in Eighteenth-Century Britain. The Economic History Review 55: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Maxine. 2004. In Pursuit of Luxury: Global History and British Consumer Goods in the Eighteenth Century. Past & Present 182: 85–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bickham, Troy. 2008. Eating the Empire: Intersections of Food, Cookery and Imperialism in Eighteenth-century Britain. Past & Present 198: 71–109. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Ann. 2016. Conrad Gessner’s Paratexts. Gesnerus 73: 73–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisseret, David. 1989. Henry IV: King of France. Boston: Unwin Hyman. [Google Scholar]

- Camille, Michael. 1992. Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Victor. 1984. The Painter-Etcher: The Role of the Original Printmaker. In Regency to Empire: French Printmaking 1715–1814. Edited by Victor I. Carlson and John W. Ittmann. Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Annemarie Weyl. 2006. Donors in the Frames of Icons: Living in the Borders of Byzantine Art. Gesta 45: 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castriota, David. 1995. The Ara Pacis Augustae and the Imagery of Abundance in Later Greek and Early Roman Imperial Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coquery, Natacha. 2004. The Language of Success: Marketing and Distributing Semi-Luxury Goods in Eighteenth-Century Paris. Journal of Design History 17: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corsembleu de Desmahis, Joseph-François-Edouard de. 1756. Femme (Morale). In Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers. Paris: Briasson, David, Le Breton, Durand, vol. 6, pp. 472–75. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, Carlo, and Sara Matthews-Grieco. 1991. Historical Perspectives on Breastfeeding: Two Essays. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Historical Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- d’Alembert, Jean-Baptiste le Rond. 1765. Nature. In Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des arts et des Métiers. Paris: Briasson, David, Le Breton, Durand, vol. 11, pp. 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- de Goncourt, Edmond. 1865. Fragonard; Etude Contenant 4 Dessins Graves a l’Eau-Forte. Paris: E. Dentu. [Google Scholar]

- de Riquetti, Victor, Marquis de Mirabeau, François Quesnay, and John Adams. 1763. Philosophie Rurale ou, Économie Générale et Politique de l’Agriculture, Reduite à l’Ordre Immuable des Loix Physiques & Morales, qui Assurent la Prospérité des Empires. Amsterdam: Les Libraires Associés. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. ; Translated by Owens Craig. 1979. The Parergon. October 9: 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diderot, Denis (ascribed by Jacques Proust). 1751. Art. In Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers. Paris: Briasson, David, Le Breton, Durand, vol. 1, pp. 713–17. [Google Scholar]

- Diderot, Denis. 1876. Le Salon 1767. In Oeuvres Complètes de Diderot: Revues sur les Editions Originales. Paris: Garnie Frères. First published in 1767. [Google Scholar]

- Diderot, Denis. 1984. Salon de 1765. Edited by Else Marie Bukdahl and Annette Lorenceau. Paris: Hermann, p. 314. First published in 1765. [Google Scholar]

- Du Monceau, Henri-Louis Duhamel. 1755. Traité des Arbres et Arbustes. Paris: HACHETTE LIVRE-BNF. [Google Scholar]

- Du Monceau, Henri-Louis Duhamel. 1768. Traité des Arbres Fruitiers. Contenant Leur Figure, Leur Description. Paris: Wentworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Du Monceau, Henri-Louis Duhamel. 1780. Des Semis et Plantations des Arbres, et de Leur Culture: Ou Méthodes pour Multiplier et élever les Arbres, les planter en Massifs & en Avenues; Former les Forêts & les Bois; les Entretenir, & Rétablir ceux qui sont Dégradés: Faisant Partie du Traité Complet des Bois & des Forêts. Paris: Chez H.L. Guerin & L.F. Delatour. [Google Scholar]

- Du Monceau, Henri-Louis Duhamel. 1801. Traité des Arbres et Arbustes Que l’on Cultive en France en Pleine Terre. Paris: Didot ainé and Lamy. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, Carol. 1973. Happy Mothers and Other New Ideas in French Art. The Art Bulletin 55: 570–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy-Vachey, Marie-Anne. 2016. Every Possible Combination Between Inspiration and Finish in Fragonard’s Oeuvre. In Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant. Edited by Perrin Stein. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, Norbert. 1994. The Civilizing Process: The History of Manners and State Formation and Civilization. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Emsley, Clive. 2014. Britain and the French Revolution. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, James Richard. 2008. The Work of France: Labor and Culture in Early Modern Times, 1350–1800. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhring, Peter. 2015. Publishers, Sellers and Market. In A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660–1715. Edited by Peter Fuhring, Louis Marchesano, Rémi Mathis and Vanessa Selbach. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, pp. 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gasbarrone, Lisa. 1986. Blindness or Oversight? A Closer Look at Rousseu’s Dictionnaire des Botanique. French Forum 11: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gazette de France. 1790. Paris: Imprimerie Royale, December 24.

- Genette, Gérard. 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy, Étienne-François. 1743. Traité de la Matière Médicale ou De L’histoire, des Vertus, du Choix et de L’usage des Remèdes Simples. Paris: Jean deSaint & Charles Saillant. [Google Scholar]

- Gillispie, Charles Coulston. 2004. Science and Polity in France: The End of the Old Regime. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrich, Ernst H. 1984. The Sense of Order: A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Arts. New York: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Goubert, Pierre. 1968. Legitimate Fecundity and Infant Mortality in France during the Eighteenth Century: A Comparison. Daedalus 97: 593–603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Green, Nicholas. 1990. The Spectacle of Nature: Landscape and Bourgeois Culture in Nineteenth-Century France. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Elizabeth. 1986. The Plant Collections of an Eighteenth-Century Virtuoso. Garden History 14: 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, David L. 2017. Mapping and ‘Natural’ Garden Design in Late Eighteenth-Century France: The Example of Georges-Louis Le Rouge. SiteLINES: A Journal of Place 12: 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Henry. 2009. The Bourgeois Revolution in France, 1789–1815. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, Christopher. 1991. The Chaste Tree: Vitex Agnus Castus. Pharmacy in History 33: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, Phillippa. 2012. Trade Cards in 18th-Century Consumer Culture: Circulation, and Exchange in Commercial and Collecting Spaces. Material Culture Review 74– 75: 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, John Dixon. 1992. Gardens and the Picturesque: Studies in the History of Landscape Architecture. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, Elizabeth. 2005. Cultivated Power: Flowers, Culture, and Politics in the Reign of Louis XIV. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Ann-Mari. 2011. Lineus’s International Correspondences: The Spread of a Revolution. In Languages of Science in the Eighteenth Century. Edited by Britt-Louise Gunnarsson. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 171–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Olive R. 1993. Commercial Foods, 1740–1820. Historical Archaeology 27: 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joullain, François Charles. 1786. Réflexions sur la Peinture et la Gravure, Accompagnées d’une Courte Dissertation sur le Commerce de la Curiosité et les Ventes en Général…. Metz: C. Lamort. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, Lillian. 2014. Roma and the Virtuous Breast. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 59/ 60: 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kalba, Laura Anne. 2012. Blue Roses and Yellow Violets: Flowers and the Cultivation of Color in Nineteenth-Century France. Representation 120: 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta, and Virginia Roehrig Kaufmann. 1991. The Sanctification of Nature: Observations on the Origins of Trompe L’oeil in Netherlandish Book Painting of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 19: 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Korsmeyer, Carolyn. 1999. Making Sense of Taste: Food and Philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa. 2007. Genre and Sex. Studies in the History of Art 72: 200–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa. 2018. The Painter’s Touch: Boucher, Chardin, Fragonard. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lefrançois, Thierry. 1981. Nicolas Bertin (1668–1736): Peintre d’Histoire. Neuilly-sur-Seine: Arthena. [Google Scholar]

- Levitine, George. 1984. French Eighteenth-Century Printmaking in Search of Cultural Assertion. In Regency To Empire: French Printmaking 1715–1814. Edited by Victor I. Carlson and John W. Ittmann. Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, Louis. 1982. Du cadre au décor ou la question de l’ornement dans la peinture. Rivista di Estetica 12: 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Meredith. 2011. Dairy Queens: The Politics of Pastoral Architecture from Catherine de’ Medici to Marie-Antoinette. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, Rémi. 2015. What Is a Printmaker? In A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660–1715. Edited by Peter Fuhring, Louis Marchesano, Rémi Mathis and Vanessa Selbach. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- May, Georges. 1973. Observations on an Allegory: The Frontispiece of the ‘Encyclopédie’. Diderot Studies 16: 159–74. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister Johnson, William. 2016. The Rise and Fall Fine Art Print in of the Eighteenth-Century France. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- McTighe, Shella. 1998. Abraham Bosse and the Language of Artisans: Genre and Perspective in the Académie Royale De Peinture Et De Sculpture, 1648–1670. Oxford Art Journal 21: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, Ronald L. 1960. The Interpretation of the ‘Tableau Economique’. Economica, New Series 27: 322–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellby, Julie L. 2009. Printmaker’s Abbreviations. In Graphic Arts: Exhibitions, Acquisitions, and Other Highlights from the Graphic Arts Collection, Princeton University Library. February 6. Available online: https://www.princeton.edu/~graphicarts/2009/02/printmakers_abbreviations.html (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Mennell, Stephen. 1996. All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present, 2nd ed. Urbana: University of Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Mercure du France. 1783. Paris: Panckoucke.

- Milam, Jennifer. 2007. The Art of Imagining Childhood in the Eighteenth Century. In Stories for Children, Histories of Childhood. Volume II: Literature. Edited by Rosie Findlay and Sébastien Salbayre. Tours: Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais, pp. 139–69. [Google Scholar]

- Milam, Jennifer. 2015. Rococo Representations of Interspecies Sensuality and the Pursuit of ‘Volupté’. The Art Bulletin 97: 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Philipp. 1786–1789. Dictionnaire des Jardiniers et des Cultivateurs. Brussels: B. Le Francq. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Paul, and Lynn Roberts. 1996. A History of European Picture Frames. London: P. Mitchell in association with M. Hoberton. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, Myra D. 1996. What Goes Around: Borders and frames in French Manuscripts. The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 54: 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, Melanie. 2016. Figures in a Foreign Landscape: Aspects of Liminality in Shaun Tan’s The Arrival. In Landscapes of Liminality: Between Space and Place. Edited by Dara Downey, Ian Kinane and Elizabeth Parker. London: Rowman and Littlefield Limited, pp. 137–52. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, Harry S. 1989. Historical Records, Origins, and Development of the Edible Cultivar Groups of Cucurbita Pepo (Cucurbitaceae). Economic Botany 43: 423–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, Antoine Augustin. 1781. Expériences et Réflexions Relatives à l’Analyse du Bled et des Farines. Paris: Nyon & Barrois l’aîné. [Google Scholar]

- Pasa, Barbara. 2020. Industrial Design and Artistic Expression: The Challenge of Legal Protection. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Péréfixe de Beaumont, Hardouin de. 1661. Histoire du Roy Henry le Grand Composée par Messire Hardouin de Perefixe Evesque de Rodez, Cy-Devant Precepteur du Roy. Amsterdam: Elzevir, Daniel & Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Portalis, Roger Le Baron and Béraldi, Henri. 1880–1882. Les Graveurs du Dix-Huitième Siècle. Paris: Morgand et Fatout. [Google Scholar]

- Portalis, Roger le Baron. 1889. Honoré Fragonard: Sa vie et Son Oeuvre. Paris: J. Rothschild. [Google Scholar]

- Prang, Christoph. 2014. The Creative Power of Semiotics: Umberto Eco’s ‘The Name of the Rose’. Comparative Literature 66: 420–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost, Bertrand. 2013. Des putti et de leurs guirlandes: Points, noeuds, monde. In Questions d’Ornements. XVe–XVIIIe Siècles. Edited by Ralph Dekoninck, Caroline Heering and Michel Lefftz. Turnhaut: Brepols Publishers, pp. 144–53. [Google Scholar]

- Purnell, Carolyn. 2017. The Sensational Past: How the Enlightenment Changed the Way We Use Our Senses. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Quesnay, François. 1756. Fermiers. In Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers. Paris: Briasson, David, Le Breton, Durand, vol. 6, pp. 528–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ranson, Pierre. 1778. Oeuvres Contenant un Recueil de Trophées, Attributs, Cartouches, Vases, Fleurs Ornemens Et Plusieurs Desseins Agréables pour Broder des Fauteuils; Composés et Dessinés par Ranson, et gravés par Berthaut et Voysard. Paris: Chez Esnauts et Rapilly. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, Richard Cullen. 2019. Sensory Media: Communication and the Enlightenment in the Atlantic World. In A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Enlightenment. Edited by Anna C. Vila. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 203–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur, Paul. 2006. On Translation. Translated by Eileen Brennan. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Pierre. 1987. Fragonard. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau. 1780–1782. Fragmens pour tin Dicionnaire des termes de Botanique. In Collection Complete des Oeuvres de J. J. Rousseau. Geneva: Moulton et du Peyron, vol. 7, pp. 477–530. First published in 1771–1774. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1823. Letters Elementaire sur La Botanique. Paris: F. Louis. First published in 1763. [Google Scholar]

- Rozier, François, and Marc-Antoine-Louis Claret de La Tourrette. 1787. Démonstrations élémentaires de Botanique…, Troisième ed. Lyon: Bruyset Frères. [Google Scholar]

- Rudy, Elizabeth M. 2013. On the Market: Selling Etchings in Eighteenth-Century France. In Artists and Amateurs: Etching in 18th-Century France. Edited by Perrin Stein. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 40–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff, Allan R. 2015. Arcadian Visions: Pastoral Influences on Poetry, Painting and the Design of Landscape. Havertown: Windgather Press. [Google Scholar]

- Savedoff, Barbara E. 1999. Frames. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 57: 345–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarry, Elaine. 2005. Imagining Flowers: Perceptual Mimesis (Particularly Delphinium). In Regimes of Description: In the Archive of the Eighteenth Century. Edited by John Bender and Michael Marrian. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg, Ruediger. 2001. Treatment for rhe Premenstrual Syndrome with Agnus Castus Fruit Extract: Prospective, Randomised, Placebo Controlled Study. BMJ: British Medical Journal 322: 134–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schiebinger, Londa. 1993. Why Mammals Are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-century Natural History. The American Historical Review 98: 382–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnapper, Antoine. 1990. The Debut of the Royal Academy. In The French Academy: Classicism and Its Antagonists. Edited by June Hargrove. Newark: University of Delaware Press, pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, Beverly. 1982. French Flower Books of the Early Nineteenth Century. Nineteenth-Century French Studies 11: 63. [Google Scholar]

- Sexauer, Benjamin. 1976. English and French Agriculture in the Late Eighteenth Century. Agricultural History 50: 491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Sheriff, Mary D. 1990. Fragonard: Art and Eroticism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, Patricia. 2015. Puppy Love: Fragonard’s Dogs and Dounets. Notes in the History of Art 34: 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Pamela H. 2005. Cereal Architecture: Late-Nineteenth-Century Grain Palaces and Crop Art. Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 10: 269–82. [Google Scholar]

- Slights, William W. E. 1989. The Edifying Margins of Renaissance English Books. Renaissance Quarterly 42: 682–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smentek, Kristel. 2007. Sex, Sentiment, and Speculation: The Market for Genre Prints on the Eve of the French Revolution. Studies in the History of Art 72: 221–43. [Google Scholar]

- Smentek, Kristel. 2014. Mariette and the Science of the Connoisseur in Eighteenth-Century Europe. Dorchester: Doreset Press. [Google Scholar]

- Société de l’histoire de l’art français. 1862. Archives de l’Art Français: Recueil de Documents Inédits Relatifs à l’Histoire des Arts en France. Paris: Librairie Tross. [Google Scholar]

- Spary, Emma C. 2000. Utopia’s Garden: French Natural History from Old Regime to Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spary, Emma C. 2012. Eating the Enlightenment Food and the Sciences in Paris, 1670–1760. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spary, Emma C. 2014. Feeding France: New Sciences of Food, 1760–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stallybrass, Peter Visible. 2011. Visible, and Invisible Letters. In Visible Writings: Cultures, Forms, Readings. Edited by Marija Dalbello and Mary Shaw. New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Stearn, William T. 1962. The Influence of Leyden on Botany in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. The British Journal for the History of Science 1: 137–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltzfus, Ben. 2013. Magritte’s Dialectical Affinities: Hegel, Sade, and Goethe. Journal of Narrative Theory 43: 111–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symes, Michael. 2014. The Concept of the ‘Fabrique’. Garden History 42: 120–27. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Sean J. 1987. Pendants and Commercial Ploys: Formal and Informal Relationships in the Work of Nicolas Delaunay. Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 50: 509–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teute, Fredrika J. 2000. The Loves of the Plants; Or, the Cross-Fertilization of Science and Desire at the End of the Eighteenth Century. Huntington Library Quarterly 63: 319–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Victor W. 2008. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Vaggi, Gianni. 1987. The Economics of François Quesnay. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, Gal. 2018. Maternal Breast-feeding and Its Substitutes in 19th-Century French Art. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Claire. 1995. Shop Design and the Display of Goods in Eighteenth-Century London. Journal of Design History 8: 157–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watelet, Claude-Henri, and Pierre-Charles Levesque. 1756. Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers. Paris: Briasson, David, Le Breton, Durand, pp. 351–52. [Google Scholar]

- Watelet, Claude-Henri, and Pierre-Charles Levesque. 1792. Dictionnaire Des Arts De Peinture, Sculpture Et Gravure. Paris: L.F. Prault2. [Google Scholar]

- West, Shearer. 1996. Framing Hegemony: Economics, Luxury and Family Continuity in the Country House Portrait. In The Rhetoric of the Frame: Essays on the Boundaries of the Artwork. Edited by Paul Duro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wiebenson, Dora. 1978. The Picturesque Garden in France. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wildenstein, Georges. 1960. The Paintings of Fragonard. Aylesbury: Phaidon, Hunt: Barnard and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Rogel L. 2001. Linnaeus: Prince of Botanists. In Botanophilia in Eighteenth-Century France: The Spirit of the Enlightenment. Edited by Rogel L. Williams. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Woudstra, Jan. 2000. The Use of Flowering Plants in the Late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth Century. Garden History 28: 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The misspelling of the word Beignets is in the title of the original print. |

| 2 | In the lower right corner, “Par son très humble and très obeissant servituer.” McAllister Johnson (2016). |

| 3 | My deep gratitude goes to Dr. Yuval Sapir, Curator of Herbarium at the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, The George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, Tel Aviv University, for his knowledgeable insights and help with categorizing the vegetation throughout this research, and to Alexandra Dvorkin for her contribution and insights on the botanical illustrations. |

| 4 | In the upper right corner of the rectangular plinth on which the image rests: “H Fragonard inv et del”. these letterings indicate the medium of the original was drawing, “Peint” was added when copying a painted image. |

| 5 | “M. de Launay, Graveur du Roi, de l’Académie Royale de Peinture & de Sculpture, vient de publier une nouvelle estampe d’après M. Fragonard, Peinture du Roi & de la même Académie; elle a pour titre Les Beignets, elle est digne des talents des deux Artistes; elle fait suite à celles qui ont paru il y a quelque temps sous le […]; elle sera suivi cette année de trois autres de la même grandeur & du même format qui compléteront les six Estampes précieuses de ce genre, que M. de Launay se propose de publier”. Mercure du France (1783, pp. 137–138). The print was the third in a series of six created by de Launay, who decided to pair every two prints in the series as pendants, as his advertisements indicate. |

| 6 | Watelet and Levesque write “conformite dans […] l’effet”, which I translate as having a similar effect on the viewer. Watelet and Levesque (1792, vol. 5, pp. 1–2); McAllister Johnson (2016, pp. 1–2, 58); Taylor (1987, p. 516). |

| 7 | “[L]es véritables amateurs de l’art ne recherchent dans les tableux que leur merite, & ne negligent pas d’acquerir un tableux precieux que n’a pas de pendant: mais ceux qui ne s׳occupent que de la decoration, sont peu difficiles sur le merite des ouvrages, & beaucuop sur leur correspnondence. […]. aujourdui qu’on n’achete guere des estampes qu’en qualite de meubles, un graveur ne peut se promettre un debit sur d’une estampe, s’il ne l’accompagne pas d’un estampe correspondante. des qu’il a grave une plache, ul faut qu’il se hate graver le pendant.” Watelet and Levesque (1792, vol. 5, pp. 2–3). |

| 8 | Printmakers did not have equal rights in the Académie and were perceived in principle as subordinate. Carlson (1984, pp. 25–26); McAllister Johnson (2016, pp. 78–80). |

| 9 | “[D]épend de l’imagination de ses auteurs et ne peut être assujetti à d’autres lois que celles de leur génie, […] en doit être entièrement libre” (Société de l’histoire de l’art français 1862, p. 262). |

| 10 | |

| 11 | Spary (2014, pp. 33, 95); Sheriff (1990, p. 101). In general, squashes and the rest of the gourd family stood out in period recipes, as they offered prolonged satiety at a lower cost. |

| 12 | The original painting is lost. There are similar versions such as “The Class Teacher”. Mercure du France (1783, pp. 137–38). Portalis (1889, pp. 187, 299); Wildenstein (1960, p. 302; cat. 468, 469); Goubert (1968, p. 600). |

| 13 | Nicolas de Launay after Jean Honoré Fragonard, L’Heureuse Fecondite, Etching and engraving, 26.9 cm × 30.5 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New-York; Nicolas de Launay after Jean Baptiste Le Prince, Le bonheur du Ménage, 1778, engraving and etching, 29 cm × 32.4 cm, The British Museum, London; Nicolas Delaunay and Jean-Louis Delignon after Sigmund Freudenberger, La Félicité Villageoise, ca. 1770–1780, etching and engraving, 29.3 cm × 34 cm, Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University. |

| 14 | “Fermiers, sont ceux qui afferment & font valoir les biens des campagnes, & qui procurent. Les richesses & les ressources les plus essentielles pour le soûtien de l’état; ainsi l’emploi du fermier est un objet très-important dans le royaume, & mérite une grande attention”. Quesnay (1756, vol. 6, pp. 528–29). |

| 15 | “Plus les laboureurs sont riches, plus ils augmentent par leurs facultés le produit des terres, & la puissance de la nation.” Quesnay (1756, vol. 6, p. 533). |

| 16 | More prints from the series include the names and coat of arms of aristocrats such as Louis Gabriel, Marquis de Véri Raionard, Madame Marquise d’Ambert. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | The importance of “motherly feelings” and enjoyment in child-rearing had a didactic function to reflect and shape the social perception of parenting. For more on this, see Duncan (1973); Lajer-Burcharth (2007). |

| 19 | “Renfermée dans les devoirs de femme & de mère, elle consacre ses jours à la pratique des vertus obscures: occupée du gouvernement de sa famille, elle règne sur son mari par la complaisance, sur ses enfants par la douceur, sur ses domestiques par la bonté: sa maison est la demeure des sentiments religieux, de la piété filiale, de l’amour conjugal, de la tendresse maternelle, de l’ordre, de la paix […], l’indigent qui se présente à sa porte, n’en est jamais repoussé […].” Corsembleu de Desmahis (1756, vol. 6, p. 475). |

| 20 | Spary (2014, pp. 89–90, 93, 114–57, 244–45). On eighteenth-century food produce and market, see Jones (1993). |

| 21 | Martin (2011, p. 143). Further reading on cooking, food and status in the French Enlightenment, see Bickham (2008, pp. 73–78). Mennell (1996, pp. 69–82, 108–26). |

| 22 | Ruff (2015, p. 70); Stearn (1962, pp. 138–44). The Enlightenment paid special attention to nature and to man’s direct sensual and emotional relation with it. Teute (2000, p. 319); Hyde (2005, pp. 122–26). |

| 23 | |

| 24 | “Belles Pyramids de Fleurs Blanches”. Duhamel Du Monceau (1755, vol. 1, p. 295). |

| 25 | “Les uns disent qu’il est très-utile pour réprimer les feux de la Luxure […], & dissipe les sales imaginations qui viennent pendant le sommeil.” Geoffroy (1743, vol. 5, section 2, p. 75). |

| 26 | |

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | “Je parcours de tems mon portefeuille au coin de mon feu; cela me distrait de mes maux et me console de mes misères. Je sens que je redeviens tout à fait enfant.” Rousseau (1823, vol. 29, sct. 1, p. 140). |

| 30 | |

| 31 | |

| 32 | “Le graveur en taille-douce est proprement un prosateur qui se propose de rendre un poète d’une langue une autre […]. En qualité de le style de traditeur d’un peinture, le graveur doit montrer le talent et de style de son original […]. Lorsque le graveur a été un homme intelligent, au premier aspect de l’estampe, la manière du peintre est sentie”. Diderot ([1765] 1984, p. 314). |

| 33 | “Il faut avouer aussi qu ‘ à côté de la peinture, le rôle de la gravure est bien froid.” Diderot ([1767] 1876, vol. 11, p. 367). |

| 34 | La Trahison des images, 1928–1929, oil on canvas, 60.33 cm × 81.12 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Stoltzfus (2013); Prang (2014, pp. 420–21). |

| 35 | Taylor (1987, p. 526). Artists, like botanist, sought to create from unmediated experience, seeking to see, touch, and smell the original, copying from reality and often visited galleries to do so. Green (1990, p. 113). |

| 36 | “Rousseau responds to the challenge of botany ingeniously and energetically […], He produces a variety of botanical texts, each one an attempt to fill the sign, or at least to bridge the gap between words and things.” Gasbarrone (1986, p. 8). |

| 37 | |

| 38 | “Je vous supplie, si vous le trouvez bon, de l’orner (le tableau) d’un peu de corniche, car il en besoin, afin que, en le considérant en toutes ses parties, le rayons de l’œil soient retenus et non point épars au dehors, en recevant les espèces des autres objet…”. Marin (1982, p. 18). |

| 39 | To use Derrida’s definition of the “Parergon”, Derrida (1979, p. 21). |

| 40 | This article is based on my PhD dissertation on Framing Decoration in the long eighteenth century’s reproductive art. My deepest thanks go to Prof. Gal Ventura, who was not only a wonderful dissertation adviser, but is a true mentor; to Dr. Sharon Assaf for her great contribution and her thoughts; and to Prof. Daniel M. Unger for constructing this brilliant Special Issue. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abramovitch, T. Cutting Edges: Professional Hierarchy vs. Creative Identity in Nicolas de Launay’s Fine Art Prints. Arts 2021, 10, 66. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/arts10030066

Abramovitch T. Cutting Edges: Professional Hierarchy vs. Creative Identity in Nicolas de Launay’s Fine Art Prints. Arts. 2021; 10(3):66. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/arts10030066

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbramovitch, Tamara. 2021. "Cutting Edges: Professional Hierarchy vs. Creative Identity in Nicolas de Launay’s Fine Art Prints" Arts 10, no. 3: 66. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/arts10030066