Autochthonous Human and Canine Strongyloides stercoralis Infection in Europe: Report of a Human Case in An Italian Teen and Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

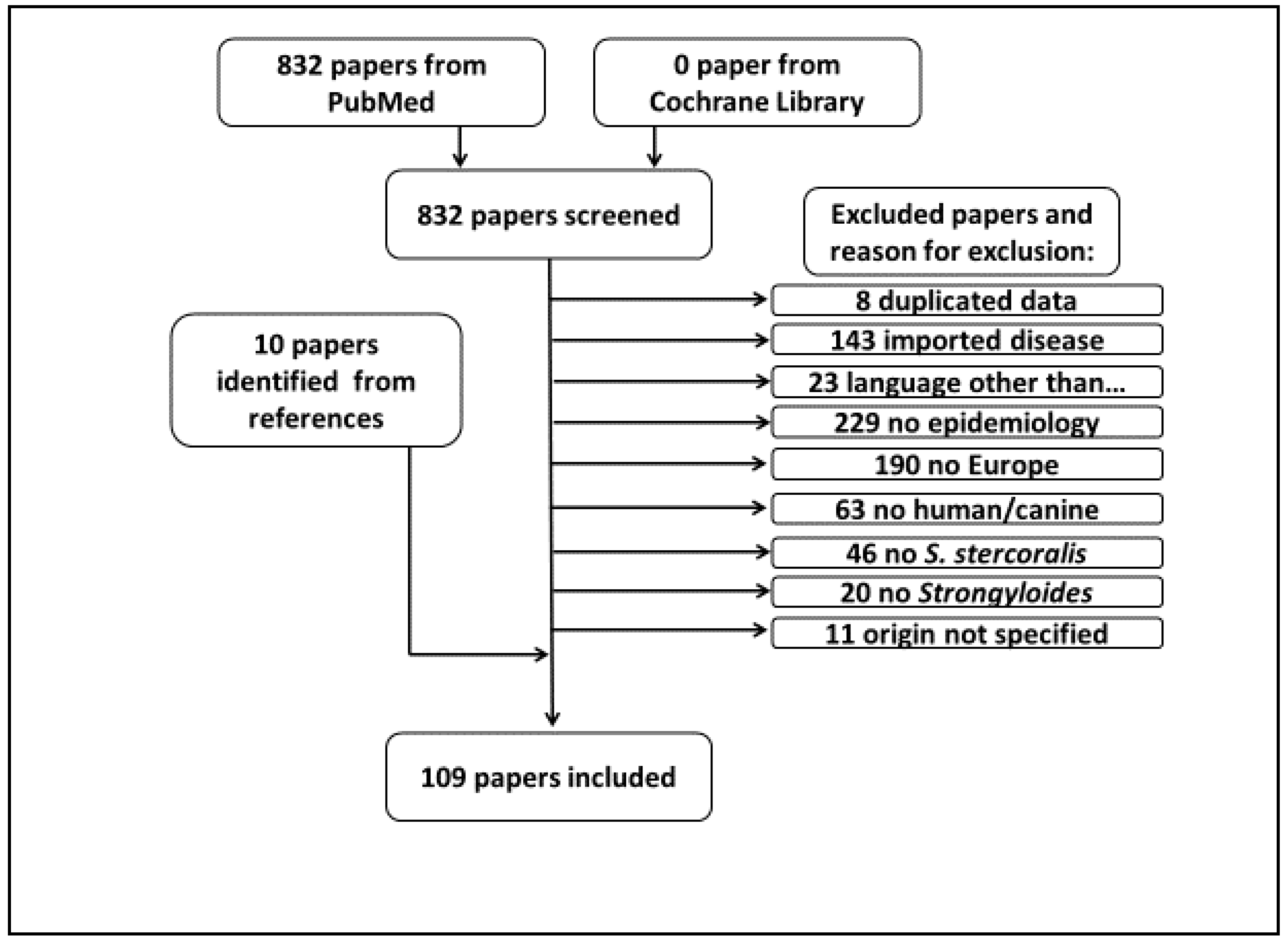

2. Materials and Methods

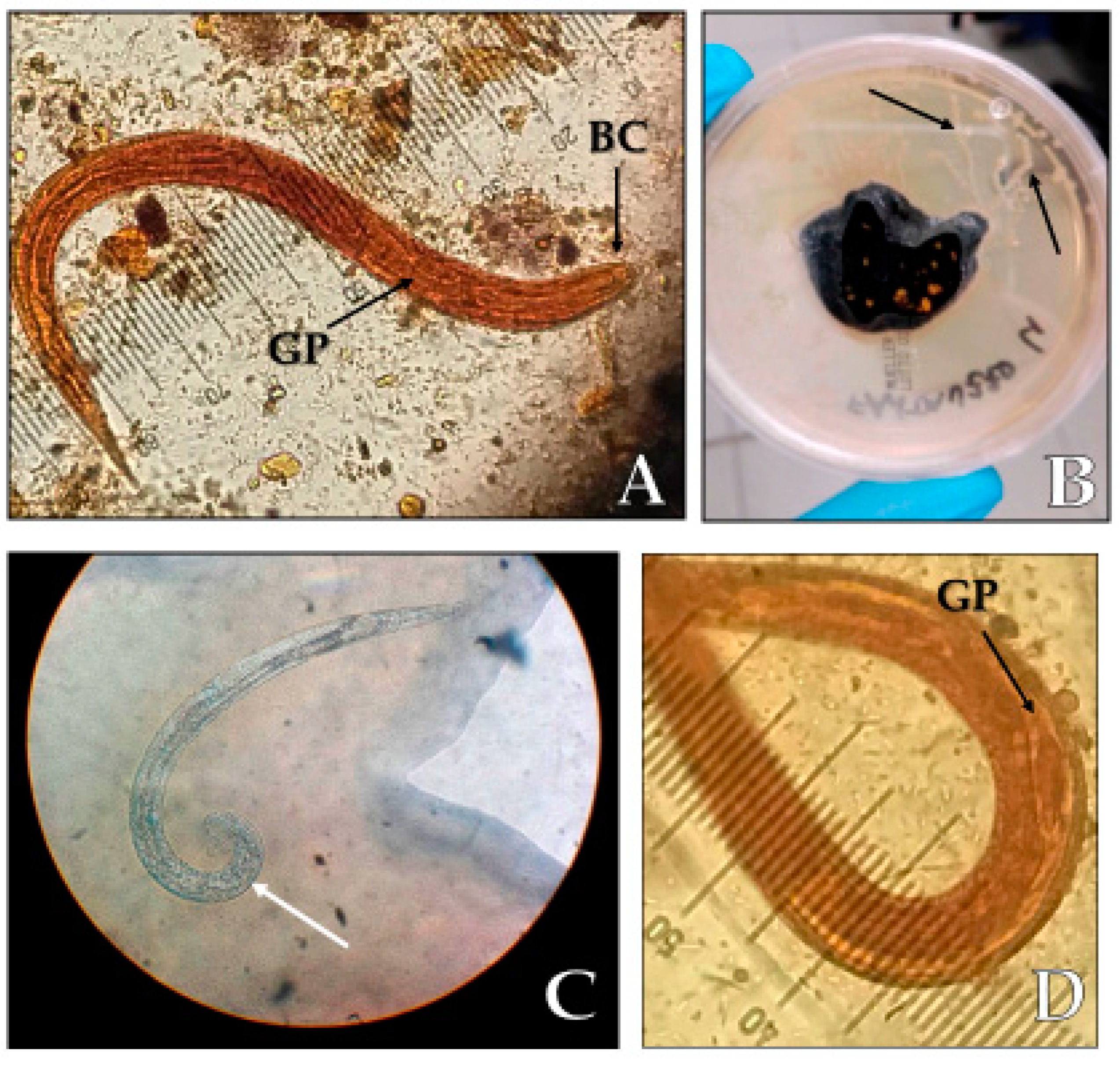

3. Case Report

4. Literature Review, Including the Previously Unpublished Case

4.1. Human Case Reports and Case Series

4.2. Human Aggregated Cases

4.3. Human Prevalence and Epidemiology Studies

4.4. Canine Strongyloidiasis Case Reports, Aggregated Cases and Prevalence

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nutman, T.B. Human infection with Strongyloides stercoralis and other related Strongyloides species. Parasitology 2017, 144, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roxby, A.C.; Gottlieb, G.S.; Limaye, A.P. Strongyloidiasis in transplant patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 1411–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jourdan, P.M.; Lamberton, P.H.L.; Fenwick, A.; Addiss, D.G. Soil-transmitted helminth infections. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2018, 391, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thamsborg, S.M.; Ketzis, J.; Horii, Y.; Matthews, J.B. Strongyloides spp. infections of veterinary importance. Parasitology 2017, 144, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keiser, P.B.; Nutman, T.B. Strongyloides stercoralis in the Immunocompromised Population. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schär, F.; Trostdorf, U.; Giardina, F.; Khieu, V.; Muth, S.; Marti, H.; Vounatsou, P.; Odermatt, P. Strongyloides stercoralis: Global Distribution and Risk Factors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buonfrate, D.; Requena-Mendez, A.; Angheben, A.; Muñoz, J.; Gobbi, F.; Van Den Ende, J.; Bisoffi, Z. Severe strongyloidiasis: A systematic review of case reports. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buonfrate, D.; Perandin, F.; Formenti, F.; Bisoffi, Z. A retrospective study comparing agar plate culture, indirect immunofluorescence and real-time PCR for the diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Parasitology 2017, 144, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, M.C.; Montgomery, S.P. Soil-transmitted Helminthiasis in the United States: A systematic review—1940–2010. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 85, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Júnior, A.F.; Gonçalves-Pires, M.R.F.; Silva, D.a.O.; Gonçalves, A.L.R.; Costa-Cruz, J.M. Parasitological and serological diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in domesticated dogs from southeastern Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 136, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.M.; Wong-Riley, M.; Sharkey, K.A. Functional alterations in jejunal myenteric neurons during inflammation in nematode-infected guinea pigs. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 275, G922–G935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, M.C.; Nolan, T.J. Endoparasite prevalence and recurrence across different age groups of dogs and cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 166, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paulos, D.; Addis, M.; Fromsa Merga, A.; Mekibib, B. Studies on the prevalence of gastrointestinal helminthes of dogs and owners awareness about zoonotic dog parasites in Hawassa Town, Ethiopia. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 2012, 4, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riggio, F.; Mannella, R.; Ariti, G.; Perrucci, S. Intestinal and lung parasites in owned dogs and cats from central Italy. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 193, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, K.; Suzuki, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Sakai, T.; Asano, R. Prevalence of dogs with intestinal parasites in Tochigi, Japan in 1979, 1991 and 2002. Vet. Parasitol. 2004, 120, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štrkolcová, G.; Goldová, M.; Bocková, E.; Mojžišová, J. The roundworm Strongyloides stercoralis in children, dogs, and soil inside and outside a segregated settlement in Eastern Slovakia: Frequent but hardly detectable parasite. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, A.L.R.; Machado, G.A.; Gonçalves-Pires, M.R.F.; Ferreira-Júnior, A.; Silva, D.a.O.; Costa-Cruz, J.M. Evaluation of strongyloidiasis in kennel dogs and keepers by parasitological and serological assays. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 147, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayasu, E.; Aung, M.P.P.T.H.H.; Hortiwakul, T.; Hino, A.; Tanaka, T.; Higashiarakawa, M.; Olia, A.; Taniguchi, T.; Win, S.M.T.; Ohashi, I.; et al. A possible origin population of pathogenic intestinal nematodes, Strongyloides stercoralis, unveiled by molecular phylogeny. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaleta, T.G.; Lok, J.B. Advances in the Molecular and Cellular Biology of Strongyloides spp. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2019, 6, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barratt, J.L.N.; Lane, M.; Talundzic, E.; Richins, T.; Robertson, G.; Formenti, F.; Pritt, B.; Verocai, G.; Nascimento de Souza, J.; Mato Soares, N.; et al. A global genotyping survey of Strongyloides stercoralis and Strongyloides fuelleborni using deep amplicon sequencing. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takano, Y.; Minakami, K.; Kodama, S.; Matsuo, T.; Satozono, I. Cross Infection of Strongyloides between Humans and Dogs in the Amami Islands, Japan. Trop. Med. Health 2009, 37, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscolo, M.; Gobbo, M.; Mantovani, W.; Degani, M.; Anselmi, M.; Monteiro, G.B.; Marocco, S.; Angheben, A.; Mistretta, M.; Santacatterina, M.; et al. Evaluation of an indirect immunofluorescence assay for strongyloidiasis as a tool for diagnosis and follow-up. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. CVI 2007, 14, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hasegawa, H.; Kalousova, B.; McLennan, M.R.; Modry, D.; Profousova-Psenkova, I.; Shutt-Phillips, K.A.; Todd, A.; Huffman, M.A.; Petrzelkova, K.J. Strongyloides infections of humans and great apes in Dzanga-Sangha Protected Areas, Central African Republic and in degraded forest fragments in Bulindi, Uganda. Parasitol. Int. 2016, 65, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, J.J.; Canales, M.; Polman, K.; Ziem, J.; Brienen, E.A.T.; Polderman, A.M.; van Lieshout, L. Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in faecal samples using real-time PCR. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 103, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pypen, Y.; Oris, E.; Meeuwissen, J.; Vander Laenen, M.; Van Gompel, F.; Coppens, G. Late onset of Strongyloides stercoralis meningitis in a retired Belgian miner. Acta Clin. Belg. 2015, 70, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Goede, E.; Martens, M.; Van Rooy, S.; VanMoerkerke, I. A case of systemic strongyloidiasis in an ex-coal miner with idiopathic colitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1995, 7, 807–809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arsić-Arsenijević, V.; Dzamić, A.; Dzamić, Z.; Milobratović, D.; Tomić, D. Fatal Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a young woman with lupus glomerulonephritis. J. Nephrol. 2005, 18, 787–790. [Google Scholar]

- Pichard, D.C.; Hensley, J.R.; Williams, E.; Apolo, A.B.; Klion, A.D.; DiGiovanna, J.J. Rapid development of migratory, linear, and serpiginous lesions in association with immunosuppression. J. Am. Acad. Derm. 2014, 70, 1130–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Topić, M.B.; Čuković-Čavka, S.; Brinar, M.; Kalauz, M.; Škrlec, I.; Majerović, M. Terminal ileum resection as a trigger for Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection and ensuing serial sepsis in a 37-year-old patient with complicated Crohn’s disease: A case report. Z. Gastroenterol. 2018, 56, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harcourt-Webster, J.N.; Scaravilli, F.; Darwish, A.H. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in an HIV positive patient. J. Clin. Pathol. 1991, 44, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osio, A.; Demongeot, C.; Battistella, M.; Lhuillier, E.; Zafrani, L.; Vignon-Pennamen, M.-D. Periumbilical purpura: Challenge and answer. Diagnosis: Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection. Am. J. Derm. 2014, 36, 899–900, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glize, B.; Malvy, D. Autochthonous strongyloidiasis, Bordeaux area, South-Western France. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2014, 12, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, F.; Favory, R.; Augusto, D.; Moukassa, D.; Dutoit, E.; Mathieu, D. Massive haemoptysis associated with pulmonary Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfestation. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2005, 22, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masseau, A.; Hervier, B.; Leclair, F.; Grossi, O.; Mosnier, J.-F.; Hamidou, M. Strongyloides stercoralis infection simulating polyarteritis nodosa. Rev. Med. Interne 2005, 26, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coton, T.; Chaudier, B.; Rey, P.; Molinier, S.; Wade, B.; Sang, V.; Lemaitre, X.; Gras, C. Indigenous strongyloidiasis: Apropos of a case. Med. Trop. Rev. Corps Sante Colon. 1999, 59, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Doury, P. Autochthonous anguilluliasis in France. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1990 1993, 86, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Poirriez, J.; Becquet, R.; Dutoit, E.; Crepin, M.; Cousin, J. Autochthonous strongyloidiasis in the north of France. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1990 1992, 85, 292–295. [Google Scholar]

- Pinel, C.; Pelloux, H.; Bureau du Colombier, J.; Ambroise-Thomas, P. Endemic strongyloidiasis in the Grenoble region. Presse Medicale Paris Fr. 1983 1991, 20, 1899–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, T.; Schau, A.; Winkler, C. Autochthonous strongyloidosis in an 81-year-old woman. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2002, 114, 405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Kechagia, M.; Stamoulos, K.; Skarmoutsou, N.; Katsika, P.; Basoulis, D.; Martsoukou, M.; Pavlou, K.; Fakiri, E.M. Rare Case of Strongyloides stercoralis Hyperinfection in a Greek Patient with Chronic Eosinophilia. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 3, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xouris, D.; Vafiadis-Zoumbulis, I.; Papaxoinis, K.; Bamias, G.; Karamanolis, G.; Vlachogiannakos, J.; Ladas, S.D. Possible Strongyloides stercoralis infection diagnosed by videocapsule endoscopy in an immunocompetent patient with devastating diarrhea. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2012, 25, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grapsa, D.; Petrakakou, E.; Botsoli-Stergiou, E.; Mikou, P.; Athanassiadou, P.; Karkampasi, A.; Ioakim-Liossi, A. Strongyloides stercoralis in a bronchial washing specimen processed as conventional and Thin-Prep smears: Report of a case and a review of the literature. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2009, 37, 903–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasidou, D.; Maniatis, M.; Vassiou, K.; Damani, E.; Vakalis, N.; Fesoulidis, I.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Strongyloides hyperinfection in a patient with sarcoidosis. Respirology 2003, 8, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamias, G.; Toskas, A.; Psychogiou, M.; Delladetsima, I.; Siakavellas, S.I.; Dimarogona, K.; Daikos, G.L. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome presenting as enterococcal meningitis in a low-endemicity area. Virulence 2010, 1, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beltrame, A.; Bortesi, L.; Benini, M.; Bisoffi, Z. A case of chronic strongyloidiasis diagnosed by histopathological study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 77, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lo Gullo, A.; Aragona, C.O.; Ardesia, M.; Versace, A.G.; Cascio, A.; Saitta, A.; Mandraffino, G. A Strongyloides stercoralis infection presenting as arthritis of sternoclavicular joint. Mod. Rheumatol. 2016, 26, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, F.; Lepanto, D.; Annibali, O.; Cerchiara, E.; Tirindelli, M.C.; Bianchi, A.; Sedati, P.; Muda, A.O.; Avvisati, G. Sytemic strongyloidiasis and primary aspergillosis of digestive tract in a patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2011, 35, 978–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caramaschi, P.; Marocco, S.; Gobbo, M.; La Verde, V.; Volpe, A.; Bambara, L.; Biasi, D. Systemic lupus erythematosus and strongyloidiasis: A multifaceted connection. Lupus 2010, 19, 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tassara, R.; Parodi, L.; Brignone, M.; Di Pede, E.; Scogna, M.; Minetti, F.; Bonanni, F. Eosinophilia and Strongyloides stercoralis infestation: Case report. Infez. Med. 1999, 7, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corsetti, M.; Basilisco, G.; Pometta, R.; Allocca, M.; Conte, D. Mistaken diagnosis of eosinophilic colitis. Ital. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1999, 31, 607–609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gulletta, M.; Chatel, G.; Pavia, M.; Signorini, L.; Tebaldi, A.; Bombana, E.; Carosi, G. AIDS and strongyloidiasis. Int. J. STD AIDS 1998, 9, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casati, A.; Cornero, G.; Muttini, S.; Tresoldi, M.; Gallioli, G.; Torri, G. Hyperacute pneumonitis in a patient with overwhelming Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 1996, 13, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariotta, S.; Pallone, G.; Li Bianchi, E.; Gilardi, G.; Bisetti, A. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in a case of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Panminerva Med. 1996, 38, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ronchetto, F.; Pistono, P.G.; Guasco, C. Strongyloides stercoralis in a region of northwestern Italy. An epidemiological note and presentation of a case of eosinophilic infiltration of the lung. Recenti Prog. Med. 1995, 86, 234–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hanck, C.; Holzer, R.B. Chronic abdominal pain and eosinophilia in a patient from Southern Italy. Schweiz. Rundsch. Med. Prax. 1993, 82, 186–188. [Google Scholar]

- Brügemann, J.; Kampinga, G.A.; Riezebos-Brilman, A.; Stek, C.J.; Edel, J.P.; van der Bij, W.; Sprenger, H.G.; Zijlstra, F. Two donor-related infections in a heart transplant recipient: One common, the other a tropical surprise. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2010, 29, 1433–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordheim, E.; Olafsson Storrø, M.; Natvik, A.K.; Birkeland Kro, G.; Midtvedt, K.; Varberg Reisaeter, A.; Hagness, M.; Fevang, B.; Pettersen, F.O. Donor-derived strongyloidiasis after organ transplantation in Norway. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2019, 21, e13008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rego Silva, J.; Macau, R.A.; Mateus, A.; Cruz, P.; Aleixo, M.J.; Brito, M.; Alcobia, A.; Oliveira, C.; Ramos, A. Successful Treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis Hyperinfection in a Kidney Transplant Recipient: Case Report. Transpl. Proc. 2018, 50, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluhovschi, G.; Gluhovschi, C.; Velciov, S.; Ratiu, I.; Bozdog, G.; Taban, S.; Petrica, L. “Surprise” in the evolution of chronic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with severe strongyloidiasis under corticotherapy: “hygienic paradox”? Ren. Fail. 2013, 35, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drug, V.; Haliga, R.; Akbar, Q.; Mihai, C.; Cijevschi Prelipcean, C.; Stanciu, C. Ascites with Strongyloides stercoralis in a patient with acute alcoholic pancreatitis and liver cirrhosis. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2009, 18, 367–369. [Google Scholar]

- Galiano, A.; Trelis, M.; Moya-Herráiz, Á.; Sánchez-Plumed, J.; Merino, J.F. Donor-derived Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome after simultaneous kidney/pancreas transplantation. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 51, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pacheco-Tenza, M.I.; Ruiz-Maciá, J.A.; Navarro-Cots, M.; Gregori-Colomé, J.; Cepeda-Rodrigo, J.M.; Llenas-García, J. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a Spanish regional hospital: Not just an imported disease. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2018, 36, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, S.N.; Barreiro Alonso, E.; Liguori Ljoka, M.E.; Díaz Trapiella, A. Strongyloidiasis native to Asturias. Semergen 2017, 43, e6–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban Ronda, V.; Franco Serrano, J.; Briones Urtiaga, M.L. Pulmonary Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2016, 52, 442–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Junyent, J.; Paredes-Zapata, D.; de las Parras, E.R.; González-Costello, J.; Ruiz-Arranz, Á.; Cañizares, R.; Saugar, J.M.; Muñoz, J. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction in Stool Detects Transmission of Strongyloides stercoralis from an Infected Donor to Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 897–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández Rodríguez, C.; Enríquez-Matas, A.; Sanchéz Millán, M.; Mielgo Ballesteros, R.; Jukic Beteta, K.; Valdez Tejeda, M.; Almonte Durán, P.; Levano Vasquez, J.; Sánchez González, M. Strongyloides stercoralis infection: A series of cases diagnosed in an allergy department in Spain. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2012, 22, 437–459. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ruiz, M.Á.; Arboleda-Sánchez, J.A.; Del Arco-Jiménez, A.; Fernandez-Sánchez, F. Severe pneumonia in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, M.J.; Ruiz-Perez-Pipaon, M.; Cañas, E.; Bernal, C.; Gavilan, F. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection transmitted by liver allograft in a transplant recipient. Am. J. Transpl. 2009, 9, 2637–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán Catalán, S.; Crespo Albiach, J.F.; Morales García, A.I.; Gavela Martínez, E.; Górriz Teruel, J.L.; Pallardó Mateu, L.M. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in renal transplant recipients. Nefrol. Publ. Soc. Esp. Nefrol. 2009, 29, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayayo, E.; Gomez-Aracil, V.; Azua-Blanco, J.; Azua-Romeo, J.; Capilla, J.; Mayayo, R. Strongyloides stercolaris infection mimicking a malignant tumour in a non-immunocompromised patient. Diagnosis by bronchoalveolar cytology. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 58, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olmos, M.; Gracia, S.; Villoria, F.; Salesa, R.; González-Macías, J. Disseminated strongyloidiasis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 15, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Vázquez, C.; González Mediero, G.; Núñez, M.; Pérez, S.; García-Fernaández, J.M.; Gimena, B. Strongyloides stercoralis in the south of Galicia. An. Med. Interna Madr. Spain 1984 2003, 20, 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Cremades Romero, M.J.; Martínez García, M.A.; Menéndez Villanueva, R.; Cremades Romero, M.L.; Pemán García, J.P. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a cortico-dependent patient with chronic airflow obstruction. Arch. Bronconeumol. 1996, 32, 430–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, N.; Dávila, M.F.; Gijón, H.; Pérez, M.A. Strongyloidiasis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 1992, 10, 431–432. [Google Scholar]

- del Mar Ortiz Romero, M.; León Martínez, M.D.; de Los Ángeles Muñoz Pérez, M.; Altuna Cuesta, A.; Cano Sánchez, A.; Hernández Martínez, J. Strongyloides stercoralys: Una peculiar forma de exacerbación en la EPOC. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2008, 44, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, C.; Gayaf, M.; Ozsoz, A.; Sahin, B.; Aksel, N.; Karasu, I.; Aydogdu, Z.; Turgay, N. Pulmonary Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2014, 11, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korkmaz, U.; Duman, A.E.; Gurkan, B.; Sirin, G.; Topcu, Y.; Dindar, G.; Gurbuz, Y.; Senturk, O. Nonresponsive celiac disease due to Strongyloides stercoralis infestation. Intern. Med. 2012, 51, 881–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oztürk, G.; Aydınlı, B.; Celebi, F.; Gürsan, N. Gastric perforation caused by Strongyloides stercoralis: A case report. Ulus. Travma Ve Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011, 17, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintop, L.; Cakar, B.; Hokelek, M.; Bektas, A.; Yildiz, L.; Karaoglanoglu, M. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and bronchial asthma: A case report. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2010, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sav, T.; Yaman, O.; Gunal, A.I.; Oymak, O.; Utas, C. Peritonitis associated with Strongyloides stercoralis in a patient undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. NDT Plus 2009, 2, 390–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaldiz, M.; Hakverdi, S.; Aslan, A.; Temiz, M.; Culha, G. Gastric infection by Strongyloides stercoralis: A case report. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 20, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gulbas, Z.; Kebapci, M.; Pasaoglu, O.; Vardareli, E. Successful ivermectin treatment of hepatic strongyloidiasis presenting with severe eosinophilia. South. Med. J. 2004, 97, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinleyici, E.C.; Dogan, N.; Ucar, B.; Ilhan, H. Strongyloidiasis associated with amebiasis and giardiaisis in an immunocompetent boy presented with acute abdomen. Korean J. Parasitol. 2003, 41, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steiner, B.; Riebold, D.; Wolff, D.; Freund, M.; Reisinger, E.C. Strongyloides stercoralis eggs in a urethral smear after bone marrow transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 1280–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, A.; Fätkenheuer, G.; Salzberger, B.; Schrappe, M.; Diehl, V.; Franzen, C. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a patient with AIDS and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1946 1998, 123, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juchems, M.S.; Niess, J.H.; Leder, G.; Barth, T.F.; Adler, G.; Brambs, H.-J.; Wagner, M. Strongyloides stercoralis: A rare cause of obstructive duodenal stenosis. Digestion 2008, 77, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Perez, A.; Roure Díez, S.; Belhassen-Garcia, M.; Torrús-Tendero, D.; Perez-Arellano, J.L.; Cabezas, T.; Soler, C.; Díaz-Menéndez, M.; Navarro, M.; Treviño, B.; et al. Management of severe strongyloidiasis attended at reference centers in Spain. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zammarchi, L.; Vellere, I.; Stella, L.; Bartalesi, F.; Strohmeyer, M.; Bartoloni, A. Spectrum and burden of neglected tropical diseases observed in an infectious and tropical diseases unit in Florence, Italy (2000–2015). Intern. Emerg. Med. 2017, 12, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geri, G.; Rabbat, A.; Mayaux, J.; Zafrani, L.; Chalumeau-Lemoine, L.; Guidet, B.; Azoulay, E.; Pène, F. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome: A case series and a review of the literature. Infection 2015, 43, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivasi, F.; Pampiglione, S.; Boldorini, R.; Cardinale, L. Histopathology of gastric and duodenal Strongyloides stercoralis locations in fifteen immunocompromised subjects. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2006, 130, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Calabuig, D.; Igual Adell, R.; Oltra Alcaraz, C.; Sánchez Sánchez, P.; Bustamante Balen, M.; Parra Godoy, F.; Nagore Enguidanos, E. Agricultural occupation and strongyloidiasis. A case-control study. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2001, 201, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaval, J.F.; Mansuy, J.M.; Villeneuve, L.; Cassaing, S. A retrospective study of autochthonous strongyloïdiasis in Région Midi-Pyrénées (Southwestern France). Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 16, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Calabuig, D.; Oltra Alcaraz, C.; Igual Adell, R.; Parra Godoy, F.; Martínez Sánchez, J.; Ángel Rodenas, C.; Llario Sanjuán, M.; Sanjuán Bautista, M.T. Treinta casos de estrongiloidiasis en un centro de atención primaria: Características y posibles complicaciones. Aten. Primaria 1998, 21, 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Germanaud, J.; Padonou, C.; Poisson, D. Systematic parasitic coprologic testing. Value in hospital kitchen staff. Presse Medicale Paris Fr. 1983 1992, 21, 1513–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicki, W.; Eder, M.; Mazal, P.; Mayer, F.J.; Sengölge, G.; Wagner, L. Prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection and hyperinfection syndrome among renal allograft recipients in Central Europe. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem Kivrak, E.; Atalay Şahar, E.; Can, H.; Döşkaya, M.; Yilmaz, M.; Pullukçu, H.; Caner, A.; Töz, H.; Gürüz, A.Y.; Işikgöz Taşbakan, M. Screening of immunocompromised patients at risk of strongyloidiasis in western Turkey using ELISA and real-time PCR. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 47, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buonfrate, D.; Baldissera, M.; Abrescia, F.; Bassetti, M.; Caramaschi, G.; Giobbia, M.; Mascarello, M.; Rodari, P.; Scattolo, N.; Napoletano, G.; et al. Epidemiology of Strongyloides stercoralis in northern Italy: Results of a multicentre case-control study, February 2013 to July 2014. Euro Surveill. 2016, 21, 30310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valerio, L.; Roure, S.; Fernández-Rivas, G.; Basile, L.; Martínez-Cuevas, O.; Ballesteros, Á.-L.; Ramos, X.; Sabrià, M. North Metropolitan Working Group on Imported Diseases. Strongyloides stercoralis, the hidden worm. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 70 cases diagnosed in the North Metropolitan Area of Barcelona, Spain, 2003–2012. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 107, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zukiewicz, M.; Kaczmarski, M.; Topczewska, M.; Sidor, K.; Tomaszewska, B. Epidemiological and clinical picture of parasitic infections in the group of children and adolescents from north-east region of Poland. Wiad Parazytol. 2011, 57, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Grande, R.; Ranzi, M.L.; Restelli, A.; Maraschini, A.; Perego, L.; Torresani, E. Intestinal parasitosis prevalence in outpatients and inpatients of Cã Granda IRCCS Foundation—Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico of Milan: Data comparison between 1984–1985 and 2007–2009. Infez. Med. 2011, 19, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Köksal, F.; Başlanti, I.; Samasti, M. A retrospective evaluation of the prevalence of intestinal parasites in Istanbul, Turkey. Turk. Parazitoloji Derg. 2010, 34, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Abrescia, F.F.; Falda, A.; Caramaschi, G.; Scalzini, A.; Gobbi, F.; Angheben, A.; Gobbo, M.; Schiavon, R.; Rovere, P.; Bisoffi, Z. Reemergence of strongyloidiasis, northern Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1531–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirisi, M.; Salvador, E.; Bisoffi, Z.; Gobbo, M.; Smirne, C.; Gigli, C.; Minisini, R.; Fortina, G.; Bellomo, G.; Bartoli, E. Unsuspected strongyloidiasis in hospitalised elderly patients with and without eosinophilia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006, 12, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alcaraz, C.O.; Adell, R.I.; Sánchez, P.S.; Blasco, M.J.V.; Sánchez, O.A.; Auñón, A.S.; Calabuig, D.R. Characteristics and geographical profile of strongyloidiasis in healthcare area 11 of the Valencian community (Spain). J. Infect. 2004, 49, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román-Sánchez, P.; Pastor-Guzmán, A.; Moreno-Guillén, S.; Igual-Adell, R.; Suñer-Generoso, S.; Tornero-Estébanez, C. High prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis among farm workers on the Mediterranean coast of Spain: Analysis of the predictive factors of infection in developed countries. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 69, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.R.; Guzman, A.P.; Guillen, S.M.; Adell, R.I.; Estruch, A.M.; Gonzalo, I.N.; Olmos, C.R. Endemic strongyloidiasis on the Spanish Mediterranean coast. QJM Mon. J. Assoc. Physicians 2001, 94, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gatti, S.; Lopes, R.; Cevini, C.; Ijaoba, B.; Bruno, A.; Bernuzzi, A.M.; de Lio, P.; Monco, A.; Scaglia, M. Intestinal parasitic infections in an institution for the mentally retarded. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2000, 94, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremades Romero, M.J.; Igual Adell, R.; Ricart Olmos, C.; Estellés Piera, F.; Pastor-Guzmán, A.; Menéndez Villanueva, R. Infection by Strongyloides stercoralis in the county of Safor, Spain. Med. Clin. (Barc.) 1997, 109, 212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Panaitescu, D.; Căpraru, T.; Bugarin, V. Study of the incidence of intestinal and systemic parasitoses in a group of children with handicaps. Roum. Arch. Microbiol. Immunol. 1995, 54, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Genta, R.M.; Gatti, S.; Linke, M.J.; Cevini, C.; Scaglia, M. Endemic strongyloidiasis in northern Italy: Clinical and immunological aspects. Q. J. Med. 1988, 68, 679–690. [Google Scholar]

- Iatta, R.; Buonfrate, D.; Paradies, P.; Cavalera, M.A.; Capogna, A.; Iarussi, F.; Šlapeta, J.; Giorli, G.; Trerotoli, P.; Bisoffi, Z.; et al. Occurrence, diagnosis and follow-up of canine strongyloidiosis in naturally infected shelter dogs. Parasitology 2019, 146, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čabanová, V.; Guimaraes, N.; Hurníková, Z.; Chovancová, G.; Urban, P.; Miterpáková, M. Endoparasites of the grey wolf (Canis lupus) in protected areas of Slovakia. Ann. Parasitol. 2017, 63, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauda, F.; Malandrucco, L.; Macrì, G.; Scarpulla, M.; De Liberato, C.; Terracciano, G.; Fichi, G.; Berrilli, F.; Perrucci, S. Leishmania infantum, Dirofilaria spp. and other endoparasite infections in kennel dogs in central Italy. Parasite Paris Fr. 2018, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kostopoulou, D.; Claerebout, E.; Arvanitis, D.; Ligda, P.; Voutzourakis, N.; Casaert, S.; Sotiraki, S. Abundance, zoonotic potential and risk factors of intestinal parasitism amongst dog and cat populations: The scenario of Crete, Greece. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wright, I.; Stafford, K.; Coles, G. The prevalence of intestinal nematodes in cats and dogs from Lancashire, north-west England. J. Small Anim. Pr. 2016, 57, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanzani, S.A.; Di Cerbo, A.R.; Gazzonis, A.L.; Genchi, M.; Rinaldi, L.; Musella, V.; Cringoli, G.; Manfredi, M.T. Canine fecal contamination in a metropolitan area (Milan, north-western Italy): Prevalence of intestinal parasites and evaluation of health risks. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 132361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mircean, V.; Györke, A.; Cozma, V. Prevalence and risk factors of Giardia duodenalis in dogs from Romania. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 184, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazahariadou, M.; Founta, A.; Papadopoulos, E.; Chliounakis, S.; Antoniadou-Sotiriadou, K.; Theodorides, Y. Gastrointestinal parasites of shepherd and hunting dogs in the Serres Prefecture, Northern Greece. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 148, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gothe, R.; Reichler, I. Spectrum of species and infection frequency of endoparasites in bitches and their puppies in south Germany. Tierarztl. Prax. 1990, 18, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkovikj, A.; Rashikj, L.; Celeska, I.; Petrov, E.A.; Angjelovski, B.; Cvetkovikj, I.; Pavlova, M.J.; Stefanovska, J. First Case of Strongyloides stercoralis Infection in a Dog in the Republic of Macedonia. Maced. Vet. Rev. 2018, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cervone, M.; Giannelli, A.; Otranto, D.; Perrucci, S. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection in an immunosuppressed dog from France. Rev. Vét. Clin. 2016, 51, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradies, P.; Iarussi, F.; Sasanelli, M.; Capogna, A.; Lia, R.P.; Zucca, D.; Greco, B.; Cantacessi, C.; Otranto, D. Occurrence of strongyloidiasis in privately owned and sheltered dogs: Clinical presentation and treatment outcome. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eydal, M.; Skirnisson, K. Strongyloides stercoralis found in imported dogs, household dogs and kennel dogs in Iceland. Icel. Agric. Sci. 2016, 29, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, K.J.; Saari, S.A.; Anttila, M. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a Finnish kennel. Acta Vet. Scand. 2007, 49, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibbons, L.M.; Jacobs, D.E.; Pilkington, J.G. Strongyloides in British greyhounds. Vet. Rec. 1988, 122, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, M.; Salvador, F.; Sánchez-Montalvá, A.; Bosch-Nicolau, P.; Molina, I. Strongyloides stercoralis infection: A systematic review of endemic cases in Spain. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viney, M.E. Strongyloides. Parasitology 2017, 144, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faust, E.C. Experimental Studies on Human and Primate Species of Strongyloides. II. The Development of Strongyloides in the Experimental Host. Am. J. Hyg. 1933, 18, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleta, T.G.; Zhou, S.; Bemm, F.M.; Schär, F.; Khieu, V.; Muth, S.; Odermatt, P.; Lok, J.B.; Streit, A. Different but overlapping populations of Strongyloides stercoralis in dogs and humans-Dogs as a possible source for zoonotic strongyloidiasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beknazarova, M.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K. Mass drug administration for the prevention human strongyloidiasis should consider concomitant treatment of dogs. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Page, W.; Judd, J.A.; Bradbury, R.S. The Unique Life Cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis and Implications for Public Health Action. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sorvillo, F.; Mori, K.; Sewake, W.; Fishman, L. Sexual transmission of Strongyloides stercoralis among homosexual men. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 1983, 59, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourée, P.; Usubillaga, R.; Viard, J.-P.; Slama, L.; Salmon, D. L’anguillulose, une parasitose de transmission sexuelle? Presse Médicale 2019, 48, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamarozzi, F.; Martello, E.; Giorli, G.; Fittipaldo, A.; Staffolani, S.; Montresor, A.; Bisoffi, Z.; Buonfrate, D. Morbidity Associated with Chronic Strongyloides stercoralis Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asdamongkol, N.; Pornsuriyasak, P.; Sungkanuparph, S. Risk factors for strongyloidiasis hyperinfection and clinical outcomes. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2006, 37, 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Requena-Méndez, A.; Buonfrate, D.; Gomez-Junyent, J.; Zammarchi, L.; Bisoffi, Z.; Muñoz, J. Evidence-Based Guidelines for Screening and Management of Strongyloidiasis in Non-Endemic Countries. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B.S.; Mawhorter, S.D. AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice Parasitic infections in solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transpl. 2013, 13, 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Features | |

| Median age (range in years) | 58 (5–86) |

| Male sex: n (%) | 60 (75%) |

| Country of Infection Exposure–[Reference] | n (%) |

| Belgium [26,27] | 2 (2.5%) |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina [28] | 1 (1.2%) |

| Bulgaria [29] | 1 (1.2%) |

| Croatia [30] | 1 (1.2%) |

| England [31] | 1 (1.2%) |

| France [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] | 11 (13.7%) |

| Germany [40] | 1 (1.2%) |

| Greece [41,42,43,44,45] | 5 (6.2%) |

| Italy [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] | 18 (22.5%) |

| Macedonia [56] | 1 (1.2%) |

| Netherlands [57] | 1 (1.2%) |

| Norway [58] | 2 (2.5%) |

| Portugal [59] | 1 (1.2%) |

| Romania [60,61] | 2 (2.5%) |

| Spain [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] | 21 (26.2%) |

| Turkey [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84] | 8 (10%) |

| Multiple EU Countries [85,86,87] | 3 (3.7%) |

| Symptoms among Symptomatic Subjects (n: 72, 90%) | n (%) |

| Nausea or vomiting | 26 (36.1%) |

| Diarrhea | 32 (44.4%) |

| Abdominal pain | 44 (61.1%) |

| Weight loss | 28 (38.9%) |

| Itching | 13 (18%) |

| Urticaria | 13 (18%) |

| Cough | 21 (29.2%) |

| Dyspnea | 13 (18%) |

| Angioedema | 4 (5.5%) |

| Fever | 29 (40.3%) |

| Asymptomatic subjects | 8 (10%) |

| Eosinophilia | 47 (58.7%) |

| Severe Strongyloidiasis | 42 (52.5%) |

| Hyperinfection Syndrome | 42 (52.5%) |

| Disseminated strongyloidiasis | 8 (10%) |

| Risk Factors among Patients with Severe Strongyloidiasis | n (%) |

| Corticosteroid therapy | 20 (47.6%) |

| Chemotherapy | 6 (14.3%) |

| Other immunosuppressive therapy | 8 (19%) |

| COPD | 5 (12%) |

| Oncohematologic disease | 3 (7.1%) |

| Solid tumor | 3 (7.1%) |

| Solid organ transplant recipient | 7 (16.7%) |

| HIV infection | 7 (16.7%) |

| Reported Risk Factors for Exposure to Infection | n (%) |

| Agriculture worker | 15 (18.7%) |

| Miners | 4 (5%) |

| Walk barefoot | 6 (7.5%) |

| Mental disorders | 2 (2.5%) |

| Dog owner | 0 (0%) |

| MSM | 2 (2.5%) |

| None reported | 51 (63.7%) |

| Diagnostic Test Performed | n/N (%) |

| Agar plate culture Positive results | 23/80 (28.7%) 9/23 (39.2%) |

| Parasitological test on stool Positive results | 62/80 (77.5%) 47/62 (75.8%) |

| Positive parasitological test on other specimens | 22/80 (27.5%) |

| Sputum | 7/22 (31.8%) |

| BAL/BA | 10/22 (45.4%) |

| Ascitic fluid/peritoneal dyalisate | 2/22 (9%) |

| Urine | 2/22 (9%) |

| Gastric/jejunal fluid | 2/22 (9%) |

| Bile | 1/22 (4.5%) |

| Urethral smear | 1/22 (4.5%) |

| Serology | 19/80 (23.7%) |

| Positive results | 13/19 (68.4%) |

| Histological examination (biopsy/autoptic finding) | 36/80 (45%) |

| Positive gastric/duodenal histologic findings | 20/36 (55.5%) |

| Positive colonic histologic findings | 5/36 (13.8%) |

| Positive liver histologic findings | 1/36 (2.7%) |

| Positive skin histologic findings | 2/36 (5.5%) |

| Positive lung/transbronchial histologic findings | 3/36 (8.3%) |

| PCR Positive PCR on stool Positive PCR on BAL | 5/80 (6.2%) 3/5 (60%) 1/5 (20%) |

| First Author and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Diagnostic Test | Country of Exposure | Area of Exposure | N. of Cases | Year of Diagnoses | Age at Diagnosis | Eosinophilia | Symptoms | Hyperinfection Syndrome/ Disseminated Strongyloidiasis | Potential Risk Factors for Infection Reported | Risk Factors for Hyperinfection or Disseminated Infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martinez-Perez A 2018 [88] | Retrospective multicentric study on severe strongyloidiasis in Spain | Detection of larvae in fresh stool samples | Spain | Canary Island | 1 | 2006 | 40 | Yes | Digestive, fever, General malaise | Yes | No | Steroids and other immunosuppresssive therapy for renal transplant |

| Zammarchi L 2017 [89] | Retrospective case series | Pt 1: Serology (ELISA); Pt 2: coprocolture | Italy | Umbria/ Tuscany | 2 | 2012–2014 | Pt 1: 70, Pt 2: 23 | Pt 1: no, Pt 2: NA | Pt 1: diarrhea, Pt 2: NA | No | Pt 1: no, Pt 2: residency in a nursing institute | Dementia; congenial mental retardation |

| Geri G 2015 [90] | Case series and review of literature | Parasitological test on stools, respiratory samples, CSF, biopsies | France | France | 4 | 1970–2013 | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | CCS (n: 111, 83%), immunosuppressive therapy (n: 33. 24.8%), CHT (n: 24. 18.1%), autoimmune disease (n: 33, 24.8%), haematological malignancy, (n: 27, 20.3%), HIV (n: 13, 10.7%) |

| Rivasi F 2006 [91] | Study on histopathologic alterations of the gastric and duodenal mucosa in Strogyloidiasis | Gastrointestinal biopsy | Italy | Modena (8), Lodi (2), and Novara (5) | 15 | 2000–2005 | 89–58 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Solid tumors (n: 3), hematological malignancy (n: 6), gastric ulcer (n: 1), CCS therapy (n: 1) |

| Rodríguez Calabuig D 2001 [92] | Case control study to investigate the relationship between occupational activities and strongyloidiasis | Direct stool examination | Spain | Valencia province | 45 | 1997–1999 | Mean age 66 | NA | 23 cough, 22 pruritus, and 13 dyspepsia; | 1 | Agriculture workers | Corticosteroids (n: 7) |

| Magnaval JF 2000 [93] | Retrospective descriptive study | Stool examination with Baermann’s method, serology (IFA) | France | Toulouse | 17 | 1991–1997 | Mean age 53.9 years (range 25–89 years) | 12 patients eosinophil count ≥ 0.6·109cells/L | asymptomatic (n: 7), chronic weakness (n: 5), abdominal pain (n: 4), urticaria (n: 3), diarrhoea (n: 2), muscle pain (n: 2), pruritus (n: 2) flatulence (n: 1), angioedemas (n: 1) | No | Farmers (n: 6), masons (n: 2), swimming pool builder (n: 1), gardener (n: 3) | Alcohol abuse (n: 1) |

| Rodríguez Calabuig D 1998 [94] | Case series and survey on workplace and domestic health conditions | Fresh stool examination and/or stool culture | Spain/France | Oliva, Valencia province | 15 (Spain) + 11 (Spain/France) | 1994–1997 | Mean age 65 | NA | 40% respiratory, 26% digestive and 26% dermatologic symptoms | No | 66.6% had some risk factor as work barefoot, drink non-potable water | Multiple (COPD, lung cancer, pulmonary fibrosis, duodenal ulcers, diverticulitis, alcoholism, steroid therapy) |

| Germanaud J 1992 [95] | Annual parasitological coprology survey among members of the hospital kitchen staff | Fresh stool examination, stool culture | France | Orléans | 1 | 1985–1990 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| First Author and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Diagnostic Test | Country of Exposure | City of Diagnosis or Where the Study Was Conducted | Level of Data Collection | N. of Cases/ Sample Size | Prevalence | Study Period | Age at Diagnosis | Eosinophilia in Positive Cases | Symptoms/ Hyperinfection Syndrome/ Disseminated Strongyloidiasis | Potential Risk Factors for Infection Reported in Positive Cases | Risk Factors for Hyperinfection or Disseminated Infection in Positive Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winnicki W 2018 [96] | Prevalence study among renal transplant recipients in a division of nephrology and dialysis | Serology (ELISA) (1 duodenal biopsy and direct smear of pleural effusion) | Austria | Wien | Hospital based | 6*/200 *(4 patients with possible exposure outside Europe) | 3% | NA | Mean age at transplantation 55.9 ± 12.3 years | No | 1 patient with hyperinfection | NA | Triple immunosuppressive therapy (tacrolimus, steroids and mycophenolate) |

| Erdem Kivrak E 2017 [97] | Prevalence study among renal transplant recipients or patients receiving hemodialysis | Serology (ELISA) + RT-PCR (direct microscopy negative) | Turkey | Izmir | Hospital based | 1/108 | 0.92% | 2013 | NA | NA | No | Walking barefoot | Diabetes mellitus, immunosuppressive therapy for renal transplant |

| Štrkolcová G 2017 [16] | Prevalence study among Roma segregated settlement and children from general population | Koga agar plate culture, Baermann technique and serology (ELISA) | Slovakia | Medzev | Community based | Fecal sample: 0/60 settlement, 0/21 outside settlement Serology: 20/60 inside settlement, 5/21 outside settlement | Seroprevalence 33.3% children from settlement, 23.8% children from general population | 2013–2015 | 1–17 | 39 children from segregated settlement and 4 children outside settlement | NA | Children from the settlement: poor hygienic conditions | NA |

| Buonfrate D 2016 [98] | Epidemiological multicenter case–control study among italian subjects > 60 years old with and without eosinophilia | Serology (ELISA + IFA) | Italy | Negrar, San Bonifacio, Treviso, Brescia, Mantova, Trieste, Udine | Outpatients blood sampling sectors of seven northern Italian hospital | 97/1137 among patients with eosinophilia; 13/1178 among patients without eosinophilia | 8% among patients with eosinophilia; 1% among patients without eosinophilia | 2013–2014 | NA | 97 patients with eosinophil count ≥500/µL | Pruritus (n: 23), skin rash (n: 13), respiratory symptoms (n: 16), abdominal pain (n: 9), diarrhoea (n: 1) | Age > 60, farm work (n: 32), walking barefoot in earlier years (n: 37) | NA |

| Valerio L 2013 [99] | Incidence study in north metropolitan area of Barcelona | Any positive test within direct fecal or sputum smear, serology (ELISA), stool culture | Spain | Barcelona | Sentinel clinicians based study | 70* newly diagnosed cases in a reference population of 406,000 over a 10-year period *only 2 patients considered autochthonous | 0.2 newly diagnosed cases per 10,000 inhabitants per year | 2003–2012 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Zukiewicz M 2011 [100] | Study on prevalence of different intestinal parasites in children (0–18) with symptoms of possible parasitosis | Microscopic stool test | Poland | Dąbrowa Białostocka | Hospital based | 7/120 | 5.83% | December 2008–May 2009 | 0–11 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Grande R 2011 [101] | Study on prevalence of different intestinal parasites in patients with symptoms of possible parasitosis | Microscopic stool test, agar coproculture and/or serology (ELISA) | Italy | Milan | Hospital based | 1/303 children; 4/189 adults | 0.33% children; 2.11% adults | 2007–2009 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Köksal F 2010 [102] | Retrospective prevalence study of intestinal parasites | Faecal concentration technique | Turkey | Istanbul | Hospital based | 2/ stool samples of patients with suspicious intestinal parasitic infections | 0.17% | 1999–2009 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Abrescia FF 2009 [103] | Preliminary Epidemiological multicenter case–control study among Italian subjects > 60 years old with and without eosinophilia | Serology (IFAT) | Italy | Mantova- Legnago | Outpatients blood sampling sectors of two northern Italian hospitals | 37/132 eligible patients | 28% | 2008 | Mean age 76,4 years, range 68–90 years | 100% (eosinophil count >500 cells/µL) | NA | Elderly (born in 1940 or earlier), agricultural area | NA |

| Pirisi M 2006 [104] | Seroprevalence study among elderly patients with and without eosinophilia | Serology (IFA and ELISA) | Italy | Novara | Hospital based | 19/100 patients with eosinophilia and 9/100 patients without eosinophilia | 19% patients with eosinophilia and 9% patients without eosinophilia | 2002–2003 | Mean age 74 years | 19 patients with eosinophil count ≥ 0.5·109cells/L | NA | Elderly, agricultural area | NA |

| Oltra-Alcaraz 2004 [105] | Retrospective, descriptive epidemiological study | Fresh stool examination, Baermann test and fecal culture | Spain | Francesc de Borja Hospital, Area 11 of La Safor, Valencia province | Hospital based, inpatients and outpatients | 473/ (261 autochthonous) | 0.33% | 1995–1999 | 21–100 years old | NA | NA | Agriculture activities (n: 124), irrigation ditches cleaners (n: 33), ditch baths (n: 6), construction activities (n: 18) | NA |

| Román-Sánchez P 2003 [106] | Prevalence study among farm workers and analysis of predictive factors of infection | Agar plate culture technique | Spain | Gandìa | Community based | 31/250 farm workers | 12.4% | 2003 | Mean age 68.6 years | NA | NA | Farm workers, (100%), history of working barefoot (97%) | Alcohol (19.3%), Smoking (74.2%), Gastrectomy (3.2%), Debilitating illness (22.5%), Corticoids (3.1%), Immunosuppressors (3.1%) |

| Román-Sánchez P 2001 [107] | Epidemiological prospective study | Direct fecal examination | Spain | Gandìa | Hospital based | 152/patients admitted to the hospital | 0.9% | 1990–1997 | Mean age 67 years | 82% (n: 125) eosinophil count > 500 cells/mm3 | Asymptomatic 41.65% (n: 63), Severe infection 13% (n: 20) | Agriculture workers | COPD (n: 44), heart disease (n: 38), solid neoplasia (n: 7), HIV infection (n: 1) |

| Gatti S 2000 [108] | Prevalence study of parasitic infections in an institution for mentally retarded | Microscopic fecal examination | Italy | Mogliano Veneto | Hospital based | 1/550 patients | 0.8% | NA | NA | NA | NA | Mental retardation | NA |

| Cremades Romero MJ, Igual Adell R 1997 [109] | Observational and descriptive prospective study | Fresh stool examination and/or fecal culture, bronchoalveolar lavage and gastric biopsy | Spain | Valencia province | Hospital Comarcal Francesc de Borja de Gandìa, inpatients and outpatients | 37 | NA | 1994–1995 | Mean age 68 years (range 51–87 years) | 65% had respiratory, digestive and/or cutaneous symptoms | Asymptomatic (n: 13), pruritus (n: 14), flatulence (n: 8), pyrosis (n: 6), epigastralgia (n: 5), nausea and vomit (n: 3), diarrhoea (n: 2), constipation (n: 2), gastrointestinal bleeding (n: 1), skin lesions (n: 2), respiratory symptoms (n: 4), meningitis (n: 1) | Farmers (n: 33) | Solid tumor (n: 2), gastrectomy (n: 1), diabetes (n: 3), alcoholic (n: 1), COPD (n: 9), asthma (n: 9) |

| Panaitescu D 1995 [110] | Prevalence study of parasitosis in children with handicaps | Agar plate culture | Romania | Bucharest | Hospital based | 21/231 | 9.9% | NA | 3–6 years | NA | NA | Children with physical and psychic handicaps | NA |

| Genta RM 1988 [111] | Prevalence study among inpatients and outpatients of Infectious Disease Department in San Matteo Hospital | Formol-ether stool concentration, coprocolture | Italy | Pavia | Hospital based | 118/4203 (48 certainly autochthonous) | 3% | 1984–1986 | Mean age 61.4 years (range 38–80 years) | 43 patients (90%) with eosinophils >5% | Gastrointestinal manifestation (n: 23; 47%), skin rash (n: 22; 46%) | Living in endemic area | Steroid treatment (n: 1), previous gastric surgery (n: 7) |

| First Author and Year of Publication | Type of Study | Diagnostic Test | Country of Exposure | City of Diagnosis | Setting of Data Collection | N. of Cases/Sample Size | Prevalence | Study Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iatta R 2018 [112] | Prevalence study and comparative study between different diagnostic tests | Coprological methods, rt-PCR on stool, serology (ELISA/IFAT) | Italy | Bari | Shelter | 36/100 (coprocolture and/or rt-PCR); 56/100 (serology) | 36% (coprological test and/or rt-PCR on feces) and 56% (adding serology) | 2017 |

| Čabanová V 2017 [113] | Epidemiologic parasitological study | Fresh stool examination (flotation method with zinc sulphate) | Slovakia | Košice | Tatra National Park, Muránska Planina National Park and Pol’ana Protected Landscape Area | NA (2 stool samples) | NA (0.8% fecal samples) | 2015–2016 |

| Sauda F 2017 [114] | Prevalence study on Leishmania infantum, Dirofilaria spp. and other endoparasite | Fresh stool examination, Baermann method | Italy | NA | Kennels in Latium and Tuscany | Not available | 0.2% | 2011–2014 |

| Štrkolcová G 2017 [16] | Prevalence study | Microscopic stool sample (KAP culture, Baermann method) and serology (ELISA) | Slovakia | Medzev | Segregated settlement and shelter | Fecal sample: 4/30 dogs in settlement, 2/20 dogs in shelter outside settlement (KAP method); 0 (Baermann method) Serology: Not performed in dogs inside settlement. 11/20 dogs in shelter outside settlement | Fecal sample: 13.3% settlement, 10% shelter outside settlement (KAP method); 0% (Baermann method) Serology: not performed in dogs inside settlement 55% in dogs in shelter outside settlement | 2013–2015 |

| Kostopoulou D [115] 2017 | Prevalence study of intestinal parasites in cats and dogs in Crete | Sedimentation, flotation, Telemann sedimentation | Greece | Crete | Household/ shelter/ shepherd dogs | 1/879 | 0.1% | 2011–2015 |

| Wright I 2016 [116] | Prevalence study of intestinal nematode in cats and dogs | FLOTAC method | England | Lancashire | Domestic dogs | 3/171 | 1.7% | NA |

| Zanzani SA 2014 [117] | Prevalence study of intestinal parasites | Coproscopy | Italy | Milan | Fecal samples collected in the metropolitan area of Milan | 4/463 fecal samples collected | 0.86% | 2010 |

| Riggio F 2013 [14] | Prevalence study of intestinal and lung parasites in cats and dogs | Coproscopy/Baermann method | Italy | Pisa | Domestic dogs | 2/239 | 0.8% | 2008–2010 |

| Mircean V 2012 [118] | Prevalence study of G. intestinalis infection | Fresh stool examination | Romania | Cluj-Napoca | Kennel/shelters/shepherd/household dogs from West, North-West, Center and North-East Romania | 2/614 | NA | 2008/2009 |

| Papazahariadou M 2007 [119] | Prevalence study of gastrointestinal parasites of shepherd and hunting dogs | Telemann’s sedimentation method | Greece | Thessaloniki | Owned dogs | 1 shepherd and 4 hunting dogs/281 | 1.8% (0.7% shepherds, 2.4% hunting dogs) | 2004–2005 |

| Gothe R 1990 [120] | Incidence study on endoparasites of bitches and their puppies | Fecal flotation | Germany | Southern Germany | Bitches and their puppies in Southern Germany | NA | 3% | NA |

| First Author and Year of Publication | Type of Study | N. of Cases | Diagnostic Test | Country of Exposure | City of Diagnosis | Wild/Kennel /Domestic Dog | Year of Diagnosis | Age of Dog | Symptoms | Severe Infection | Eosinophilia | Fatal Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basso W 2018 [113] | Case series | 3 | Sedimentation-flotation, Baermann method+/- SAFC | Belgium/ France/Switzerland | Bern | Domestic dog (n: 2), Kennel dog (n: 1) | NA | < 11 months | Gastro-intestinal signs (n: 3); itching, cough (n: 1) | No (n: 3) | NA | No (n: 3) |

| Cvetkovikj A 2018 [121] | Case report | 1 | Flotation, Baermann method | Russia | Skopje | Domestic dog | 2017 | 6 months | Diarrhea, weight loss | No | No | No |

| Cervone M 2016 [122] | Case report | 1 | Flotation, Baermann method | France | Paris | Domestic dog | NA | 10 months | Diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, vomiting, itching, cough | Yes | No | No |

| Paradies P 2017 [123] | Case series | 6 | Coproscopy/Baermann method | Italy | Bari | Shelter dog (n: 5), domestic dog (n: 1) | NA | adult | Acute (n: 1) or Chronic (n: 4) gastro-intestinal signs +/- depression (n: 2), abdominal mass (n: 1). No symptoms (n: 1) | No (n: 6) | No (n: 5), Mild (n: 1) | No (n: 5); Yes (n: 1) |

| Eydal M 2016 [124] | Screening study | 2 autochthonous household dogs + 27 imported dogs from Europe | Fresh stool examination (formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation technique or Baermann method) | Iceland/ imported dogs | Reykjavík | Kennel and domestic dogs | 1989–2016 | Asymptomatic and symptomatic (soft stool, diarrhoea, blood in feces | No | NA | No | |

| Dillard KJ 2007 [125] | Case series | 4 | Intestinal autoptic findings (n: 1); Baermann method (n: 3) | Finland | Helsinki | Kennel dog | NA | 10 weeks (n: 1); NA (n: 3) | Severe gastro-intestinal signs (n: 1), no symptoms (n: 3) | Yes (n: 1), No (n: 3) | NA | Yes (n: 1), No (n: 3) |

| Gibbons LM 1988 [126] | Case series | 20 | autoptic findings on gastrointestinal mucosa | England | NA | Kennel dogs | NA | NA | No | No | NA | NA |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ottino, L.; Buonfrate, D.; Paradies, P.; Bisoffi, Z.; Antonelli, A.; Rossolini, G.M.; Gabrielli, S.; Bartoloni, A.; Zammarchi, L. Autochthonous Human and Canine Strongyloides stercoralis Infection in Europe: Report of a Human Case in An Italian Teen and Systematic Review of the Literature. Pathogens 2020, 9, 439. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/pathogens9060439

Ottino L, Buonfrate D, Paradies P, Bisoffi Z, Antonelli A, Rossolini GM, Gabrielli S, Bartoloni A, Zammarchi L. Autochthonous Human and Canine Strongyloides stercoralis Infection in Europe: Report of a Human Case in An Italian Teen and Systematic Review of the Literature. Pathogens. 2020; 9(6):439. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/pathogens9060439

Chicago/Turabian StyleOttino, Letizia, Dora Buonfrate, Paola Paradies, Zeno Bisoffi, Alberto Antonelli, Gian Maria Rossolini, Simona Gabrielli, Alessandro Bartoloni, and Lorenzo Zammarchi. 2020. "Autochthonous Human and Canine Strongyloides stercoralis Infection in Europe: Report of a Human Case in An Italian Teen and Systematic Review of the Literature" Pathogens 9, no. 6: 439. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/pathogens9060439