The Good, the Bad and the Blend: The Strategic Role of the “Middle Leadership” in Work-Family/Life Dynamics during Remote Working

Abstract

:1. Introduction

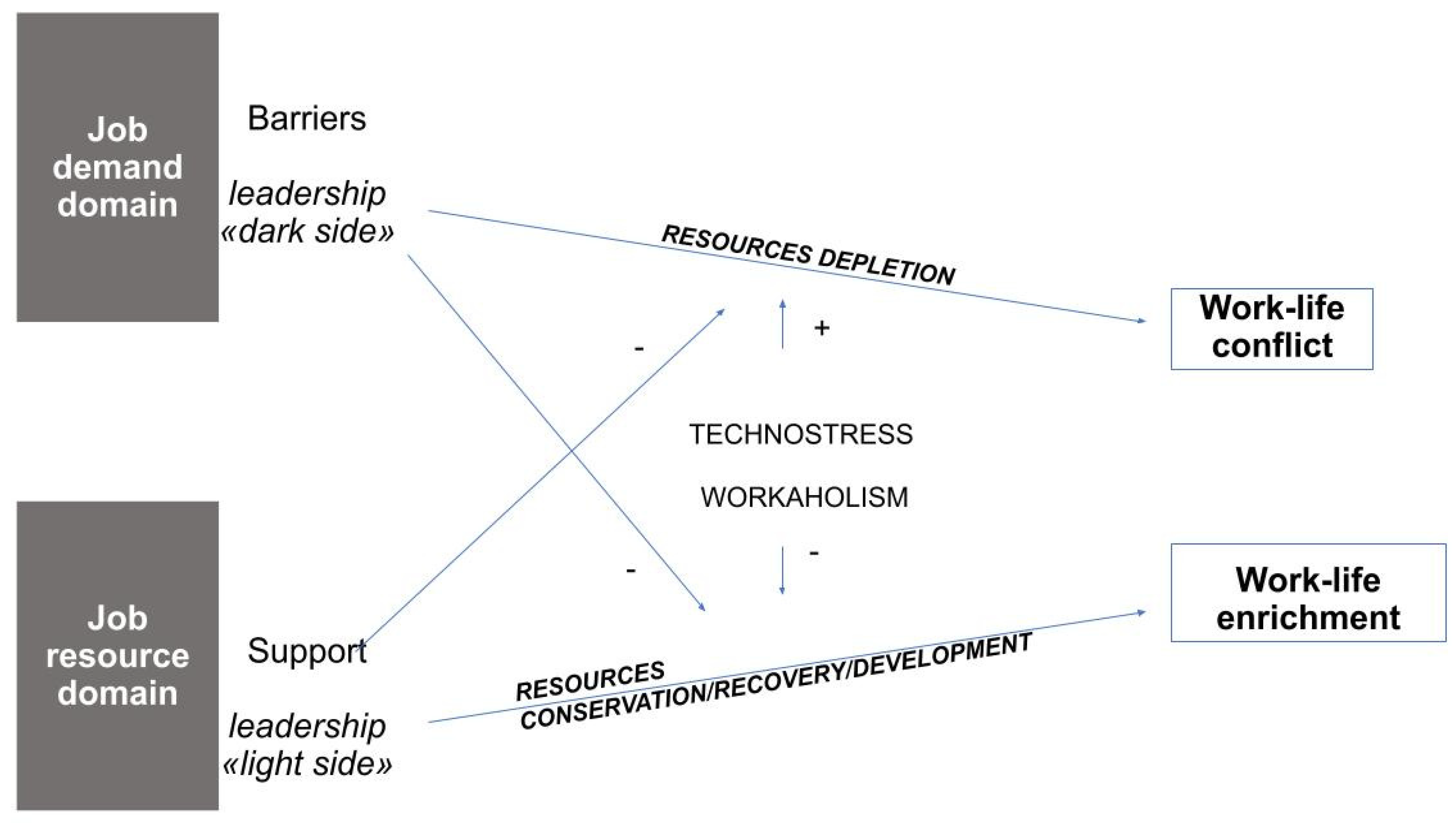

2. Work-Life Interface between Resources and Demands

3. The Challenges of the “Sandwich” Middle-Management’s Leadership in Managing Work-Life Interface

4. Exploring the Light and the Dark Side of the Leadership

5. Workaholism and Technostress’ Risks for Middle Managers during Remote Working

6. A Proposal for a Model, Looking at Gender Differences

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smart Working during the Time of the Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.som.polimi.it/en/smart-working-during-the-time-of-the-coronavirus/ (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Smart Working Observatory of the Polytechnic of Milan. Smart Working: The Future of Work Beyond the Emergency. Available online: https://www.osservatori.net/it/ricerche/osservatori-attivi/smart-working/ (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Prasad, D.K.; Rao, M.; Vaidya, D.R.; Muralidhar, B. Organizational Climate, Opportunities, Challenges and Psychological Wellbeing of the Remote Working Employees during COVID-19 Pandemic: A General Linear Model Approach with Reference to Information Technology Industry in Hyderabad. Int. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Technol. 2020, 11, 372–389. [Google Scholar]

- Snir, R.; Harpaz, I. Beyond Workaholism: Towards a General Model of Heavy Work Investment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, H.; Casper, W.J.; Wayne, J.H.; Matthews, R.A. Changes to the Work–Family Interface during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Examining Predictors and Implications Using Latent Transition Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czymara, C.S.; Langenkamp, A.; Cano, T. Cause for Concerns: Gender Inequality in Experiencing the COVID-19 Lockdown in Germany. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23, S68–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Cortese, C.; Ghislieri, C. Unsustainable Working Conditions: The Association of Destructive Leadership, Use of Technology, and Workload with Workaholism and Exhaustion. Sustainability 2019, 11, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morkevičiūtė, M.; Endriulaitienė, A.; Jočienė, E. Do Dimensions of Transformational Leadership Have an Effect on Workaholism? Balt. J. Manag. 2019, 14, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crain, T.L.; Stevens, S.C. Family-supportive Supervisor Behaviors: A Review and Recommendations for Research and Practice. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Ran, Y. Workplace Loneliness, Leader-Member Exchange and Creativity: The Cross-Level Moderating Role of Leader Compassion. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotta, M.; Meret, C.; Marchetti, G. Defining Leadership in Smart Working Contexts: A Concept Synthesis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConville, T.; Holden, L. The Filling in the Sandwich: HRM and Middle Managers in the Health Sector. Pers. Rev. 1999, 28, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D. The work-family role interface: A synthesis of the research from industrial and organizational psychology. In Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Schmitt, N.W., Highhouse, S., Weiner, I.B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; Volume 12, pp. 698–718. [Google Scholar]

- Ghislieri, C.; Gatti, P.; Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G. Work–Family Conflict and Enrichment in Nurses: Between Job Demands, Perceived Organisational Support and Work–Family Backlash. J. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 25, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D. Work–family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, M.; Carvalho, V.S.; Chambel, M.J.; Manuel, S.; Miguel, J.P.; de Fátima Reis, M. Work-Family Conflict and Employee Well-Being over Time: The Loss Spiral Effect. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrenovic, B.; Jianguo, D.; Khudaykulov, A.; Khan, M.A.S. Work-Family Conflict Impact on Psychological Safety and Psychological Well-Being: A Job Performance Model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.; Anseel, F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Bamberger, P.; Bapuji, H.; Bhave, D.P.; Choi, V.K. COVID-19 and the Workplace: Implications, Issues, and Insights for Future Research and Action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Allan, B.; Clark, M.; Hertel, G.; Hirschi, A.; Kunze, F.; Shockley, K.; Shoss, M.; Sonnentag, S.; Zacher, H. Pandemics: Implications for Research and Practice in Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Ind. Organ. Psychol. Perspect. Sci. Pract. 2021, 14, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021 Report on Gender Equality in the European Union. Available online: https://epws.org/eu-2021-report-on-gender-equality (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. A Resource Perspective on the Work–Home Interface: The Work–Home Resources Model. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahn, R.L.; Wolfe, D.M.; Quinn, R.P.; Snoek, J.D.; Rosenthal, R.A. Organizational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of Conflict between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When Work and Family Are Allies: A Theory of Work-Family Enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, B.; Schmid, T.; Floyd, S.W. The Middle Management Perspective on Strategy Process: Contributions, Synthesis, and Future Research. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 1190–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Ashford, S.J. Selling Issues to Top Management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nonaka, I. A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Procter, S.J. The Antecedents of Middle Managers’ Strategic Contribution: The Case of a Professional Bureaucracy. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1325–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, J.M.; Wooldridge, B. Middle Managers’ Divergent Strategic Activity: An Investigation of Multiple Measures of Network Centrality. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, Q.N. Emotional Balancing of Organizational Continuity and Radical Change: The Contribution of Middle Managers. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 31–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Wellbeing Costs of Technology Use during Covid-19 Remote Working: An Investigation Using the Italian Translation of the Technostress Creators Scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, M.; Ingusci, E.; Cortese, C.G.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Molino, M.; Signore, F.; Russo, V. Does the End Justify the Means? The Role of Organizational Communication among Work-from-Home Employees during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Kelliher, C. Enforced Remote Working and the Work-Life Interface during Lockdown. Gend. Manag. 2020, 35, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J. Helping Remote Workers Avoid Loneliness and Burnout. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/11/helping-remote-workers-avoid-loneliness-and-burnout (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Bloom, N.; Liang, J.; Roberts, J.; Ying, Z.J. Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2013, 130, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schein, E.H. The Corporate Culture Survival Guide; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 0-470-49483-2. [Google Scholar]

- Valentino, C.L. The Role of Middle Managers in the Transmission and Integration of Organizational Culture. J. Healthc. Manag. 2004, 49, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennis, W.G. An Invented Life: Reflections on Leadership and Change; Addison-Wesley Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992; ISBN 0-470-64057-X. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-8039-7176-9. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Open Road Integrated Media: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 978-1-4532-4517-0. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic Leadership Development: Getting to the Root of Positive Forms of Leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddams, M.; Chang, G.C. Only Human: Exploring the Nature of Weakness in Authentic Leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 1-07-183447-9. [Google Scholar]

- Riggio, R.E.; Zhu, W.; Reina, C.; Maroosis, J.A. Virtue-Based Measurement of Ethical Leadership: The Leadership Virtues Questionnaire. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2010, 62, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghislieri, C.; Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G. Work and Organizational Psychology Looks at the Fourth Industrial Revolution: How to Support Workers and Organizations? Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avolio, B.J.; Kahai, S.S. Adding the “E” to E-Leadership: How It May Impact Your Leadership. Organ. Dyn. 2003, 31, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Majchrzak, A.; Rosen, B. Leading Virtual Teams. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avolio, B.J.; Kahai, S.; Dodge, G.E. E-Leadership: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Leadersh. Q. 2000, 11, 615–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G. E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and beyond: What We Know and Where Do We Go. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, A.V.; Van Wart, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.; McCarthy, A. Defining E-leadership as Competence in ICT-mediated Communications: An Exploratory Assessment. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Van Wart, M.; Kim, S.; Wang, X.; McCarthy, A.; Ready, D. The Effects of National Cultures on Two Technologically Advanced Countries: The Case of E-leadership in South Korea and the United States. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2020, 79, 298–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzmüller, T.; Brosi, P.; Duman, D.; Welpe, I.M. How Does the Digital Transformation Affect Organizations? Key Themes of Change in Work Design and Leadership. Manag. Rev. 2018, 29, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J.B.; Bazarova, N.N. Validation and Application of Electronic Propinquity Theory to Computer-Mediated Communication in Groups. Commun. Res. 2008, 35, 622–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, B. Both Angel and Devil: The Suppressing Effect of Transformational Leadership on Proactive Employee’s Career Satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolce, V.; Vayre, E.; Molino, M.; Ghislieri, C. Far Away, So Close? The Role of Destructive Leadership in the Job Demands–Resources and Recovery Model in Emergency Telework. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P.; Molino, M.; Molinaro, D.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Ghislieri, C. Workaholism and Technostress during the Covid-19 Emergency: The Crucial Role of the Leaders on Remote Working. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer Science Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K.A. Transformational Leadership and Employee Psychological Well-Being: A Review and Directions for Future Research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, K. Supervisor Support and Work-Life Integration: A Social Identity Perspective. In Work and Life Integration: Organizational, Cultural, and Individual Perspectives; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 445–467. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J.A.; Johnson, P.J. The Impact of Workplace Support on Work–Family Role Strain. Fam. Relat. 1995, 44, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabo, A.; Spisak, B.R.; van Vugt, M. Charisma as Signal: An Evolutionary Perspective on Charismatic Leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Hambrick, D.C. It’s All about Me: Narcissistic Chief Executive Officers and Their Effects on Company Strategy and Performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 351–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.J.; Hogan, R.S. How dark side leadership personality destroys trust and degrades organizational effectiveness. Organ. People 2008, 15, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ghislieri, C.; Gatti, P. Generativity and Balance in Leadership. Leadership 2012, 8, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, B.; Schilling, J. How Bad Are the Effects of Bad Leaders? A Meta-Analysis of Destructive Leadership and Its Outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, C.; Cortese, C.G.; Molino, M.; Gatti, P. The Relationships of Meaningful Work and Narcissistic Leadership with Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, V.; Brough, P.; Daly, K. Fight, Flight or Freeze: Common Responses for Follower Coping with Toxic Leadership. Stress Health 2016, 32, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, P.; Stoner, J.; Hochwarter, W.; Kacmar, C. Coping with Abusive Supervision: The Neutralizing Effects of Ingratiation and Positive Affect on Negative Employee Outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, A.; Conway, E.; Bosak, J. Abusive supervision, employee well-being and ill-being: The moderating role of core self-evaluations. In Emotions and Organizational Governance; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoobler, J.M.; Brass, D.J. Abusive Supervision and Family Undermining as Displaced Aggression. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J. Abusive Supervision in Work Organizations: Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D. Positive Approaches to Leadership Development. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Positivity and Strengths-Based Approaches at Work; Oades, L.G., Steger, M., Delle Fave, A., Passmore, J., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, S.; Skogstad, A.; Aasland, M.S. The nature, prevalence, and outcomes of destructive leadership: A behavioral and conglomerate approach. In When Leadership Goes Wrong: Destructive Leadership, Mistakes, and Ethical Failures; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2010; pp. 145–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Barling, J. Leadership Development as an Intervention in Occupational Health Psychology. Work Stress 2010, 24, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, E.; Vonthron, A.-M. Identifying Work-Related Internet’s Uses—at Work and Outside Usual Workplaces and Hours—and Their Relationships with Work-Home Interface, Work Engagement, and Problematic Internet Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Derks, D.; van Duin, D.; Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Smartphone Use and Work–Home Interference: The Moderating Role of Social Norms and Employee Work Engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexander, A.; De Smet, A.; Mysore, M. How Companies Can Make Remote Working a Success; McKinsey: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/reimagining-the-postpandemic-workforce (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Godinic, D.; Obrenovic, B.; Khudaykulov, A. Effects of Economic Uncertainty on Mental Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context: Social Identity Disturbance, Job Uncertainty and Psychological Well-Being Model. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2020, 6, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.Y.; Anderson, M.H. The Combined Influence of Top and Middle Management Leadership Styles on Absorptive Capacity. Manag. Learn. 2012, 43, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, R.; Grover, V.; Purvis, R. Technostress: Technological Antecedents and Implications. MIS Q. 2011, 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oates, W.E. Confessions of a Workaholic: The Facts about Work Addiction; World Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M.A.; Michel, J.S.; Zhdanova, L.; Pui, S.Y.; Baltes, B.B. All Work and No Play? A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Correlates and Outcomes of Workaholism. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1836–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E. The Workaholic Family: A Clinical Perspective. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 1998, 26, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Ghislieri, C. The Role of Workaholism in the Job Demands-Resources Model. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Guglielmi, D.; Depolo, M. Overwork Climate Scale: Psychometric Properties and Relationships with Working Hard. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Nielsen, M.B.; Pallesen, S.; Gjerstad, J. The Relationship between Psychosocial Work Variables and Workaholism: Findings from a Nationally Representative Survey. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2019, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Banos, R.M.; Botella, C.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Gaggioli, A. Positive Technology: Using Interactive Technologies to Promote Positive Functioning. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E. The Dark Side of Technologies: Technostress among Users of Information and Communication Technologies. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spagnoli, P.; Balducci, C.; Fabbri, M.; Molinaro, D.; Barbato, G. Workaholism, Intensive Smartphone Use, and the Sleep-Wake Cycle: A Multiple Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Chang, C.-T.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, Z.-H. The Dark Side of Smartphone Usage: Psychological Traits, Compulsive Behavior and Technostress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, C.; Emanuel, F.; Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G.; Colombo, L. New Technologies Smart, or Harm Work-Family Boundaries Management? Gender Differences in Conflict and Enrichment Using the JD-R Theory. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gualano, M.R.; Lo Moro, G.; Voglino, G.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. Effects of Covid-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, F.; Wei, C.; Jia, Y.; Shang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D. The psychological consequences of work-family trade-offs for three cohorts of men and women. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2002, 65, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Ozeki, C. Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior–human resources research. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, L.; Ghislieri, C. The work-to-family conflict: Between theories and measures. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 15, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, M. Changing attitudes toward the male breadwinner, female homemaker family model: Influences of women’s employment and education over the lifecourse. Soc. Forces 2008, 87, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldini, M.; Saraceno, C. Social and family policies in Italy: Not totally frozen but far from structural reforms. Soc. Policy Adm. 2008, 42, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajadhyaksha, U.; Korabik, K.; Aycan, Z. Gender, gender-role ideology, and the work–family interface: A cross-cultural analysis. In Gender and the Work-Family Experience: An Intersection of Two Domains; Mills, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira da Silva, J. Why You Should Care About Unpaid Care Work. Available online: https://oecd-development-matters.org/2019/03/18/why-you-should-care-about-unpaid-care-work/ (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Pozzan, E.; Cattaneo, U. Women Health Workers: Working Relentlessly in Hospitals and at Home. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_741060/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Fisher, J.; Languilaire, J.-C.; Lawthom, R.; Nieuwenhuis, R.; Petts, R.J.; Runswick-Cole, K.; Yerkes, M.A. Community, Work, and Family in Times of COVID-19. Community Work. Fam. 2020, 23, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, K. The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Increased the Care Burden of Women and Families. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 16, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapporto Bes 2020: Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/254761 (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How Effective Is Telecommuting? Assessing the Status of Our Scientific Findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shockley, K.M.; Singla, N. Reconsidering Work—Family Interactions and Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 861–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, C.; Molino, M.; Dolce, V.; Sanseverino, D.; Presutti, M. Work-Family Conflict during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Teleworking of Administrative and Technical Staff in Healthcare. An Italian Study. Med. Lav. 2021, 112, 229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.G.; Venkatesh, V.; Ackerman, P.L. Gender and Age Differences in Employee Decisions about New Technology: An Extension to the Theory of Planned Behavior. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2005, 52, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marchiori, D.M.; Mainardes, E.W.; Rodrigues, R.G. Do Individual Characteristics Influence the Types of Technostress Reported by Workers? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; French, K.A.; Dumani, S.; Shockley, K.M. A Cross-National Meta-Analytic Examination of Predictors and Outcomes Associated with Work–Family Conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzani, L.; Dick, R. Positive Leadership in Organizations: A Systematic Review and Integrative Multi-Level Model. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Intelligenza Artificiale, Online la Strategia. Available online: https://www.mise.gov.it/index.php/it/198-notizie-stampa/2041246-intelligenza-artificiale-online-la-strategia (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- COVID-19: BACK TO THE WORKPLACE—Adapting Workplaces and Protecting Workers—Safety and Health at Work—EU-OSHA. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/covid-19-back-workplace-adapting-workplaces-and-protecting-workers/view (accessed on 12 May 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spagnoli, P.; Manuti, A.; Buono, C.; Ghislieri, C. The Good, the Bad and the Blend: The Strategic Role of the “Middle Leadership” in Work-Family/Life Dynamics during Remote Working. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 112. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/bs11080112

Spagnoli P, Manuti A, Buono C, Ghislieri C. The Good, the Bad and the Blend: The Strategic Role of the “Middle Leadership” in Work-Family/Life Dynamics during Remote Working. Behavioral Sciences. 2021; 11(8):112. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/bs11080112

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpagnoli, Paola, Amelia Manuti, Carmela Buono, and Chiara Ghislieri. 2021. "The Good, the Bad and the Blend: The Strategic Role of the “Middle Leadership” in Work-Family/Life Dynamics during Remote Working" Behavioral Sciences 11, no. 8: 112. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/bs11080112