Modulation of Long-Term Potentiation by Gamma Frequency Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation in Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

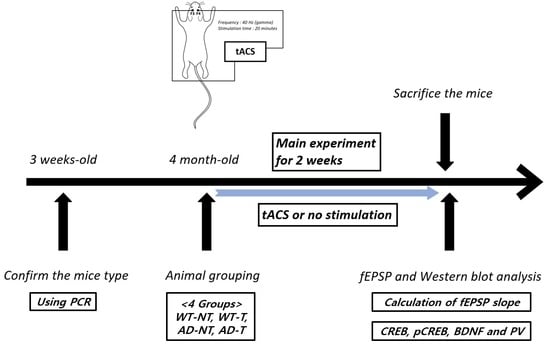

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation

2.2. Preparation of Brain Tissue

2.3. Excitatory Postsynaptic Potential (EPSP)

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. fEPSP Responses

3.2. Protein Level Analyzed by Western Blot Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hooker, K.; Bowman, S.R.; Coehlo, D.P.; Lim, S.R.; Kaye, J.; Guariglia, R.; Li, F. Behavioral change in persons with dementia: Relationships with mental and physical health of caregivers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, P453–P460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilson, R.S.; Segawa, E.; Boyle, P.A.; Anagnos, S.E.; Hizel, L.P.; Bennett, D.A. The natural history of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol. Aging 2012, 27, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jahn, H. Memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 15, 445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M.; Bryce, R.; Albanese, E.; Wimo, A.; Ribeiro, W.; Ferri, C.P. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013, 9, 63–75.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Briggs, R.; Kennelly, S.P.; O’Neill, D. Drug treatments in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epperly, T.; Dunay, M.A.; Boice, J.L. Alzheimer Disease: Pharmacologic and Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Cognitive and Functional Symptoms. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 95, 771–778. [Google Scholar]

- Bishara, D.; Sauer, J.; Taylor, D. The pharmacological management of Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurol. Psychiatry 2015, 19, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Lane, H.Y.; Lin, C.H. Brain Stimulation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajji, T.K. Transcranial Magnetic and Electrical Stimulation in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 106, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, G.J.; Taylor, J.P. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation: Treatments for cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms in the neurodegenerative dementias? Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausner, L.; Damian, M.; Sartorius, A.; Frolich, L. Efficacy and cognitive side effects of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in depressed elderly inpatients with coexisting mild cognitive impairment or dementia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarczyk, R.; Tejera, D.; Simon, B.J.; Heneka, M.T. Microglia modulation through external vagus nerve stimulation in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2018, 46, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scherder, E.J.; Deijen, J.B.; Vreeswijk, S.H.; Sergeant, J.A.; Swaab, D.F. Cranial electrostimulation (CES) in patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2002, 128, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherder, E.J.; van Tol, M.J.; Swaab, D.F. High-frequency cranial electrostimulation (CES) in patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006, 85, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Felice, A.; Castiglia, L.; Formaggio, E.; Cattelan, M.; Scarpa, B.; Manganotti, P.; Tenconi, E.; Masiero, S. Personalized transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) and physical therapy to treat motor and cognitive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized cross-over trial. Neuroimage Clin. 2019, 22, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellin, J.M.; Alagapan, S.; Lustenberger, C.; Lugo, C.E.; Alexander, M.L.; Gilmore, J.H.; Jarskog, L.F.; Fröhlich, F. Randomized trial of transcranial alternating current stimulation for treatment of auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 51, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, K.J.; Baisley, S.K.; Albizu, A.; Kartvelishvili, N.; Ding, M.; Li, W. Lasting connectivity increase and anxiety reduction via transcranial alternating current stimulation. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2018, 13, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.L.; Alagapan, S.; Lugo, C.E.; Mellin, J.M.; Lustenberger, C.; Rubinow, D.R.; Frohlich, F. Double-blind, randomized pilot clinical trial targeting alpha oscillations with transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klimke, A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Maurer, K.; Voss, U. Case Report: Successful Treatment of Therapy-Resistant OCD with Application of Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS). Brain Stimul. 2016, 9, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, A.; Paulus, W. Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abd Hamid, A.I.; Gall, C.; Speck, O.; Antal, A.; Sabel, B.A. Effects of alternating current stimulation on the healthy and diseased brain. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klein, A.S.; Donoso, J.R.; Kempter, R.; Schmitz, D.; Beed, P. Early Cortical Changes in Gamma Oscillations in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mably, A.J.; Colgin, L.L. Gamma oscillations in cognitive disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018, 52, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palop, J.J.; Chin, J.; Roberson, E.D.; Wang, J.; Thwin, M.T.; Bien-Ly, N.; Yoo, J.; Ho, K.O.; Yu, G.Q.; Kreitzer, A.; et al. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2007, 55, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herrmann, C.S.; Rach, S.; Neuling, T.; Strüber, D. Transcranial alternating current stimulation: A review of the underlying mechanisms and modulation of cognitive processes. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, M.M.; Sellers, K.K.; Frohlich, F. Transcranial alternating current stimulation modulates large-scale cortical network activity by network resonance. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 11262–11275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehler, L.; Francisco, C.O.; Uehara, M.A.; Moussavi, Z. The effect of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on cognitive function in older adults with dementia. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 3649–3653. [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi, Z.; Kimura, K.; Kehler, L.; de Oliveira Francisco, C.; Lithgow, B. A Novel Program to Improve Cognitive Function in Individuals with Dementia Using Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) and Tutored Cognitive Exercises. Front. Aging 2021, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benussi, A.; Cantoni, V.; Cotelli, M.S.; Cotelli, M.; Brattini, C.; Datta, A.; Thomas, C.; Santarnecchi, E.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Borroni, B. Exposure to gamma tACS in Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled, crossover, pilot study. Brain Stimul. 2021, 14, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaynaut, M.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Santarnecchi, E.; El Fakhri, G. Effects of modulating gamma oscillations via 40 Hz transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on Tau PET imaging in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 340. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.; Wei, P.; Wang, C.; Shan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Xie, B.; Shi, X.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, J.; et al. TRanscranial AlterNating current Stimulation FOR patients with Mild Alzheimer’s Disease (TRANSFORM-AD study): Protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 6, e12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colgin, L.L.; Moser, E.I. Gamma oscillations in the hippocampus. Physiology 2010, 25, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colgin, L.L. Rhythms of the hippocampal network. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.S.; Arons, A.; Mitchell, T.I.; Pignatelli, M.; Ryan, T.J.; Tonegawa, S. Memory retrieval by activating engram cells in mouse models of early Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2016, 531, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iaccarino, H.F.; Singer, A.C.; Martorell, A.J.; Rudenko, A.; Gao, F.; Gillingham, T.Z.; Mathys, H.; Seo, J.; Kritskiy, O.; Abdurrob, F.; et al. Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates amyloid load and modifies microglia. Nature 2016, 540, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martorell, A.J.; Paulson, A.L.; Suk, H.J.; Abdurrob, F.; Drummond, G.T.; Guan, W.; Young, J.Z.; Kim, D.N.; Kritskiy, O.; Barker, S.J.; et al. Multi-sensory Gamma Stimulation Ameliorates Alzheimer’s-Associated Pathology and Improves Cognition. Cell 2019, 177, 256–271.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oakley, H.; Cole, S.L.; Logan, S.; Maus, E.; Shao, P.; Craft, J.; Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.; Ohno, M.; Disterhoft, J.; Van Eldik, L.; et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: Potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10129–10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Huang, F.S.; Huang, C.; Yang, Z.M.; Feng, X.Z. Analysis of high-frequency stimulation-evoked synaptic plasticity in mouse hippocampal CA1 region. Sheng Li Xue Bao 2008, 60, 284–291. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M. AMPA Receptor Trafficking for Postsynaptic Potentiation. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2018, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, M.V.; Melo, C.V.; Pereira, D.B.; Carvalho, R.; Correia, S.S.; Backos, D.S.; Carvalho, A.L.; Esteban, J.A.; Duarte, C.B. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates the expression and synaptic delivery of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid receptor subunits in hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 12619–12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Figurov, A.; Pozzo-Miller, L.D.; Olafsson, P.; Wang, T.; Lu, B. Regulation of synaptic responses to high-frequency stimulation and LTP by neurotrophins in the hippocampus. Nature 1996, 381, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, M.D.; Pozzo-Miller, L. TRPC3 channels are necessary for brain-derived neurotrophic factor to activate a nonselective cationic current and to induce dendritic spine formation. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 5179–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, Y.; Wu, H.T.; Qin, X.Y.; Cao, C.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Z.Z.; Cheng, Y. Postmortem Brain, Cerebrospinal Fluid, and Blood Neurotrophic Factor Levels in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 65, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, O.; Huo, Y.; Wang, G.; Man, H.Y. Amyloid-β Induces AMPA Receptor Ubiquitination and Degradation in Primary Neurons and Human Brains of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keifer, J. Comparative Genomics of the BDNF Gene, Non-Canonical Modes of Transcriptional Regulation, and Neurological Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 2851–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, V.S.; Zhang, F.; Yizhar, O.; Deisseroth, K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature 2009, 459, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caillard, O.; Moreno, H.; Schwaller, B.; Llano, I.; Celio, M.R.; Marty, A. Role of the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin in short-term synaptic plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13372–13377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, F.; Baringer, S.L.; Neal, A.; Choi, E.Y.; Kwan, A.C. Parvalbumin-Positive Neuron Loss and Amyloid-β Deposits in the Frontal Cortex of Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 72, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesers, N.K.; Wirths, O. Loss of Hippocampal Calretinin and Parvalbumin Interneurons in the 5XFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. ASN Neuro 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Xue, F.; Xue, S.S.; Chen, Y.C.; Gu, T.; Peng, Z.W.; Wang, H.N. Isoflurane exposure regulates the cell viability and BDNF expression of astrocytes via upregulation of TREK1. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 7305–7314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, T.; Sen, N. Isoflurane-induced inactivation of CREB through histone deacetylase 4 is responsible for cognitive impairment in developing brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 96, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, W.-H.; Kim, W.-I.; Lee, J.-W.; Park, H.-K.; Song, M.-K.; Choi, I.-S.; Han, J.-Y. Modulation of Long-Term Potentiation by Gamma Frequency Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation in Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1532. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/brainsci11111532

Jeong W-H, Kim W-I, Lee J-W, Park H-K, Song M-K, Choi I-S, Han J-Y. Modulation of Long-Term Potentiation by Gamma Frequency Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation in Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(11):1532. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/brainsci11111532

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Won-Hyeong, Wang-In Kim, Jin-Won Lee, Hyeng-Kyu Park, Min-Keun Song, In-Sung Choi, and Jae-Young Han. 2021. "Modulation of Long-Term Potentiation by Gamma Frequency Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation in Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease" Brain Sciences 11, no. 11: 1532. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/brainsci11111532