The Impact of Religiosity on Tax Compliance among Turkish Self-Employed Taxpayers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

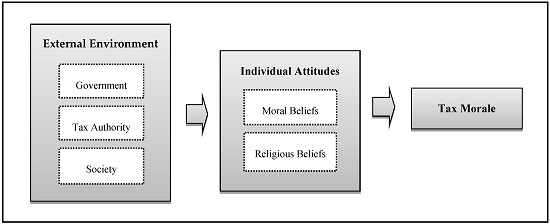

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

- H1 :General religiosity affects all dimensions of tax compliance.H1a :General religiosity affects voluntary tax compliance.H1b :General religiosity affects enforced tax compliance.

- H2 :Interpersonal religiosity affects all dimensions of tax complianceH2a :Interpersonal religiosity affects voluntary tax complianceH2b :Interpersonal religiosity affects enforced tax compliance

- H3 :Intrapersonal religiosity affects all dimensions of tax complianceH3a :Intrapersonal religiosity affects voluntary tax complianceH3b :Intrapersonal religiosity affects enforced tax compliance

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Factor Analysis

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

Scale Items Tax Compliance Items A-Voluntary Tax Compliance (VTC) Q: When I pay my taxes as required by the regulations, I do so... VTC1. ...because to me it’s obvious that this is what you do VTC2. ...to support the states or other citizens VTC3. ...because I like to contribute to everyone’s good VTC4. ...because for me it’s the natural thing to do VTC5. ...because I regard it as my duty as citizen B-Enforced Tax Compliance (ETC) Q: When I pay my taxes as required by the regulations, I do so... ETC1. ...because a great many tax audits are carried out ETC2. ...because the tax office often carries out audits ETC3. ...because I know that I will be audited ETC4. ...because the punishments for tax evasions are very severe ETC5. ...because I do not know exactly how to evade taxes without attracting attention Religiosity Items A-Interpersonal Religiosity (InterR) InterR1. I make financial contributions to my religious organization. InterR2. I enjoy spending time with others of my religious affiliation. InterR3. I keep well informed about my local religious group and have some influence in its decisions. InterR4. I enjoy working in the activities of my religious organization. B-Intrapersonal Religiosity (IntraR) IntraR1. My religious beliefs lie behind my whole approach to life. IntraR2. I spend time trying to grow in understanding of my faith. IntraR3. It is important to me to spend periods of time in private religious thought and reflection. IntraR4. Religious beliefs influence all my dealings in life. IntraR5. Religion is especially important to me because it answers many questions about the meaning of life. IntraR6. I often read books and magazines about my faith.

References

- Günter Schmölders. “Fiscal Psychology: A New Branch of Public Finance.” National Tax Journal 12 (1959): 340–45. [Google Scholar]

- D. John Hasseldine, and K. Jan Bebbington. “Blending Economic Deterrence and Fiscal Psychology Models in the Design of Responses to Tax Evasion: The New Zealand Experience.” Journal of Economic Psychology 12 (1991): 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter Schmölders. “Survey Research in Public Finance: A Behavioral Approach to Fiscal Theory.” Public Finance 25 (1970): 300–6. [Google Scholar]

- Michael W. Spicer, and Scott B. Lundstedt. “Understanding Tax Evasion.” Public Finance 31 (1976): 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Riahi-Belkaoui. “Relationship between Tax Compliance Internationally and Selected Determinants of Tax Morale.” Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 13 (2004): 135–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benno Torgler. “To Evade Taxes or Not to Evade: That is the Question.” Journal of Socio-Economics 32 (2003): 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lars P. Feld, and Benno Torgler. Tax Morale After the Reunification of Germany: Results from a Quasi-Natural Experiment. Munich: CESifo, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Benno Torgler. “Tax Morale in Asian Countries.” Journal of Asian Economics 15 (2004): 237–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benno Torgler, and Friedrich Schneider. “What Shapes Attitudes Toward Paying Taxes? Evidence from Multicultural European Countries*.” Social Science Quarterly 88 (2007): 443–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benno Torgler, Ihsan C. Demir, Alison Macintyre, and Markus Schaffner. “Causes and Consequences of Tax Morale: An Empirical Investigation.” Economic Analysis and Policy 38 (2008): 313–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benno Torgler. “Attitudes toward Paying Taxes in the USA: An Empirical Analysis The Ethics of Tax Evasion.” In The Ethics of Tax Evasion: Perspectives in Theory and Practice. Edited by Robert W. McGee. New York: Springer, 2012, pp. 269–83. [Google Scholar]

- Benno Torgler. “The Importance of Faith: Tax Morale and Religiosity.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 66 (2006): 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel M. Hungerman. “Public Goods, Hidden Income, and Tax Evasion: Some Nonstandard Results from the Warm-glow Model.” Journal of Development Economics 109 (2014): 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeff Pope, and Raihana Mohdali. “The Role of Religiosity in Tax Morale and Tax Compliance.” Australian Tax Forum 25 (2010): 565–96. [Google Scholar]

- Everett L. Worthington Jr., Nathaniel G. Wade, Terry L. Hight, Jennifer S. Ripley, Michael E. McCullough, Jack W. Berry, Michelle M. Schmitt, James T. Berry, Kevin H. Bursley, and Lynn O’Connor. “The Religious Commitment Inventory-10: Development, Refinement, and Validation of a Brief Scale for Research and Counseling.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 50 (2003): 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihana Mohdali, and Jeff Pope. “The Influence of Religiosity on Taxpayers’ Compliance Attitudes: Empirical Evidence from a Mixed-Methods Study in Malaysia.” Accounting Research Journal 27 (2014): 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erich Kirchler, and Ingrid Wahl. “Tax Compliance Inventory: TAX-I Voluntary Tax Compliance, Enforced Tax Compliance, Tax Avoidance, and Tax Evasio.” Journal of Economic Psychology 31 (2010): 331–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmanuel Saez. “Do Taxpayers Bunch at Kink Points? ” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2 (2010): 180–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiek Mokhlis. “Relevancy and Measurement of Religiosity in Consumer Behavior Research.” International Business Research 2 (2009): 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward G. Carmines, and Richard A. Zeller. Reliability and Validity Assessment. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney K. Newey, and Kenneth D. West. “Automatic lag selection in covariance matrix estimation.” Review of Economic Studies 61 (1994): 631–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan H. Gruber. “Religious Market Structure, Religious Participation, and Outcomes: Is Religion Good for You? ” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 5 (2005): 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel M. Hungerman. “Do Religious Proscriptions Matter? Evidence from a Theory-Based Test.” Journal of Human Resources 49 (2014): 1053–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondents | Sample Size: 403 | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 117 | 29.0 |

| High school | 237 | 58.8 |

| Graduate | 49 | 12.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 375 | 93.1 |

| Female | 28 | 6.9 |

| Age | ||

| Under 20 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 21–40 | 274 | 68 |

| 41 or older | 128 | 31.8 |

| Economic Branch | ||

| Services | 169 | 41.9 |

| Trade | 228 | 56.6 |

| Other | 6 | 1.5 |

| Religious Affiliation | ||

| Islam | 403 | 100.00 |

| Variable | Overall Mean | Item No. | Alpha * | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voluntary tax compliance (VTC) | 6.604 | VTC1 | 0.931 | 6.980 | 2.05632 |

| VTC2 | 6.449 | 2.10880 | |||

| VTC3 | 6.395 | 2.27757 | |||

| VTC4 | 6.473 | 2.06997 | |||

| VTC5 | 6.796 | 1.87600 | |||

| Enforced tax compliance (ETC) | 6.304 | ETC1 | 0.781 | 5.861 | 2.01006 |

| ETC2 | 5.777 | 1.99371 | |||

| ETC3 | 6.452 | 1.79677 | |||

| ETC4 | 6.035 | 2.09114 | |||

| ETC5 | 7.422 | 2.30416 | |||

| Interpersonal religiosity(InterR) | 5.649 | InterR1 | 0.681 | 6.485 | 1.98021 |

| InterR2 | 6.246 | 2.02763 | |||

| InterR3 | 4.199 | 2.69667 | |||

| InterR4 | 5.637 | 2.20687 | |||

| Intrapersonal religiosity(IntraR) | 6.674 | IntraR1 | 0.874 | 6.325 | 1.84095 |

| IntraR2 | 5.819 | 1.86602 | |||

| IntraR3 | 6.729 | 1.68420 | |||

| IntraR4 | 8.156 | 1.53820 | |||

| IntraR5 | 6.702 | 1.67084 | |||

| IntraR6 | 6.402 | 1.73412 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.VTC | 1 | |||

| 2. ETC | 0.517 ** | 1 | ||

| 3.InterR | 0.175 ** | 0.192 ** | 1 | |

| 4.IntraR | 0.251 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.691 ** | 1 |

| Item No. | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IntraR6 | 0.778 | ||

| IntraR3 | 0.777 | ||

| IntraR4 | 0.762 | ||

| InterR2 | 0.755 | ||

| IntraR1 | 0.753 | ||

| InterR4 | 0.736 | ||

| InterR2 | 0.729 | ||

| IntraR5 | 0.654 | ||

| InterR1 | 0.640 | ||

| InterR3 | 0.306 | ||

| VTC5 | 0.895 | ||

| VTC1 | 0.883 | ||

| VTC4 | 0.854 | ||

| VTC2 | 0.818 | ||

| VTC3 | 0.803 | ||

| ETC2 | 0.883 | ||

| ETC1 | 0.857 | ||

| ETC4 | 0.634 | ||

| ETC3 | 0.581 | ||

| ETC5 | 0.318 | ||

| Eigenvalue | 6.407 | 3.920 | 1.754 |

| Percent of Variance | 25.222 | 21.975 | 13.203 |

| Cumulative Percent | 25.222 | 47.197 | 60.401 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable: Voluntary Tax Compliance | Dependent Variable: Enforced Tax Compliance | ||||

| t-value | Sig. | t-value | Sig. | |||

| Intercept | 4.612 | 6.233 *** | 0.000 | 4.781 | 8.480 *** | 0.000 |

| Total Religiosity | 0.318 | 2.832 ** | 0.004 | 0.242 | 2.928 ** | 0.003 |

| R2 = 0.051 Adj. R2 = 0.048 | R2 = 0.046 Adj. R2 = 0.044 | |||||

| F (1,391) = 21.405 p < 0.000 | F (1,391) = 19.521 p < 0.000 | |||||

| Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable: Voluntary Tax Compliance | Dependent Variable: Enforced Tax Compliance | ||||

| t-value | Sig. | t-value | Sig. | |||

| Intercept | 4.481 | 5.834 *** | 0.000 | 4.670 | 7.767 *** | 0.000 |

| Interpersonal Religiosity | 0.051 | 0.526 | 0.598 | 0.033 | 0.335 | 0.737 |

| Intrapersonal Religiosity | 0.274 | 2.226 * | 0.026 | 0.216 | 1.811 | 0.070 |

| R2 = 0.053 Adj. R2 = 0.048 | R2 = 0.049 Adj. R2 = 0.044 | |||||

| F (2,390) = 11.225 p < 0.000 | F (2,390) = 10.348 p < 0.000 | |||||

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benk, S.; Budak, T.; Yüzbaşı, B.; Mohdali, R. The Impact of Religiosity on Tax Compliance among Turkish Self-Employed Taxpayers. Religions 2016, 7, 37. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rel7040037

Benk S, Budak T, Yüzbaşı B, Mohdali R. The Impact of Religiosity on Tax Compliance among Turkish Self-Employed Taxpayers. Religions. 2016; 7(4):37. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rel7040037

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenk, Serkan, Tamer Budak, Bahadır Yüzbaşı, and Raihana Mohdali. 2016. "The Impact of Religiosity on Tax Compliance among Turkish Self-Employed Taxpayers" Religions 7, no. 4: 37. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/rel7040037